Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Downey - Justinian As Achilles PDF

Uploaded by

ddOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Downey - Justinian As Achilles PDF

Uploaded by

ddCopyright:

Available Formats

American Philological Association

Justinian as Achilles

Author(s): Glanville Downey

Source: Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 71 (1940), pp.

68-77

Published by: Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/283115

Accessed: 12-12-2015 14:00 UTC

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/283115?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Philological Association and Johns Hopkins University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

68

GlanvilleDowney

[1940

VII.-Justinianas Achilles

GLANVILLE

DOWNEY

YALE UNIVERSITY

This paper studies the background and significance of the equestrian statue

of Justinian which stood on a column at Constantinople. The monument was

supposed to represent the Emperor as Achilles, a comparison chosen in order to

exemplify the prince's valor. The motives which may have prompted the erection of the statue are reviewed, and its significance as a part of the imperial

symbolism and propaganda is discussed.

Among the most notable contributionswhich have been made

in recentyears to our knowledgeof Roman and Byzantine history

are the studies of J. Gage and A. Grabar on the theologyof the

VictoriaAugusti and on the iconographyof the emperorin official

Byzantine art.' Gage has shown with admirable clarity the importance of the conceptionby which the emperor,as commanderin-chiefof the armies, came to be regarded as possessingentire

responsibilityfor their victories,and enjoying the sole and perpetual right of celebratingtriumphsfor them. The sovereigngentishumanae pateratque custos-was, by virtue of his office,an

infalliblevictor,and the power with which he was endowed in this

respectextendeditselfto all the otheractivitiesand circumstances

of his reign. The ChristianEmperorinheritedthe perpetualpower

of victoryof his pagan predecessor;in addition, he served as the

vice-gerentof God on earth,and was looked upon as the source of

all good thingsand the fountof all wisdomand law.2

These conceptionsare at the coreofthe officialart of Byzantium.

Grabar has assembled and studied the monuments-in mosaic,

sculpture,painting,ivory-carving,textileand jewellery-in which

the emperor's officialpersonalitywas constantlyset before his

subjects. A whole cycle of themesportrayedthe sovereign'sfunctions and powers,and illustratedhis automatic power of victory.

The emperorwas shown conqueringdemons and barbarians and

receivingthe homage of his captives and his vassals. One of the

1 J. Gage, "La theologie de la victoire imperiale," Revue historique CLXXI

(1933),

1-43, and "Stauros nikopoios. La victoire imperiale dans 1'empire chretien," Revue

d'histoire et de philosophie religieuses xiii (1933), 370-400; A. Grabar, L'empereur dans

Itart byzantin: recherchessur l'art officielde l'empire d'orient (Paris, Belles Lettres, 1936).

2 See also the studies cited by the present writer, T.A.P.A. LXIX (1938), 356, n. 14.

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol. lxxi]

Justinianas Achilles

69

importantthemeswas that of the royalhunt,in whichthe emperor

appeared as a gloriousand invinciblehuntsman,slayingall manner

of terrifying

wild beasts. Prowess in the chase was (the literary

textsshow) equated withprowessin war,and in thesescenes (which

had a long ancestrygoing back to Egyptian and Mesopotamian

art) the ruler'straditionalpowerof victoryin the huntwas treated

as a symbolof his triumphsover his enemies.

An importantplace in this triumphalcyclewas occupied by the

equestrian statues of the emperors,monumentswhich served admirably to depict the militaryprowessof the rulers. One of the

mostimportantofthesewas a statue ofJustinianat Constantinople.

Erected on top of a pillar in the Augustaeum,this statue occupied

one of the most commandingsites in the city. The statue itself,

beingof bronze,has disappeared,but thereare a numberof literary

descriptionsof it, notablyone by Procopius,and a drawingof the

statue has also been preserved,made in the early fifteenth

century

at the behest of the travelerand antiquary Cyriacus of Ancona.3

Procopius describes the statue as follows: 4

On the top of the columnstandsa greatbronzehorse,turnedtowards

the east, a verywonderful

sight. It seems to be moving,and to bepressingforwardsplendidly. It raisesone of its forefeet,as thoughit

wereabout to stepforward,

and plantsthe otheron thestonebeneath;

and it gathersits hindfeettogether

in readinessto move. And on this

horseis seated a bronzestatue of the emperor,like a colossus. The

statueis arrayedas Achilles;forthustheycall thedress[schema]

which

he wears. He is shod withhalf-boots

and thelegsare bare of greaves.

Then he wearsa breastplate,

in theheroicfashion,and a helmetcovers

his head, givingthe impression

thatit is nodding,and a dazzlinglight

flashesfromit. One mightsay, in poeticlanguage,thatthiswas that

starof thelate summerseason[Sirius]. He lookstowardtherisingsun,

the Persians,I believe,to stop. And in his lefthand he

commanding

3 A list of the literary sources is given by Th. Reinach, Revue des etudes grecques Ix

(1896), 82, note 3; the principal passages are also cited by P. E. Schramm, Das Herrscherbild in der Kunst des friehen Mittelalters (Vortrage der Bibliothek Warburg, ii)

Leipzig, Teubner, 1922/3, 154-155; and many of them are translated by F. W. Unger,

Quellen der byz. Kunstgeschichte I (Vienna, 1878), 137-146. The best reproduction

is provided by G. Rodenwaldt, Archaologischer Anzeiger, 1931, 331-334; this, a photograph of the original, is more accurate than the simplified line drawings which had

previously been published, e.g. by Ch. Diehl, Justinien (Paris, Leroux, 1901), 27,

fig. 11, and by H. Leclereq, "Justinien," in Cabrol-Leclercq, Dict. d'archeol. chret.et de

liturgie, viii, 1, col. 530, fig. 6428. The reproduction used as the frontispiece in the

edition of Procopius, De Aedificiis, by H. B. Dewing with the collaboration of the

present writer, in the Loeb Classical Library, is taken from Rodenwaldt's publication.

4 De A edificiis 1.2.5-12.

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

70

GlanvilleDowney

[1940

carriesa globe,thesculptorshowingin thiswaythatthewholeearthand

sea are subjectto him; he has neitherswordnor spear nor any other

whichalonehe has

weapon,but thecrossstandsuponhisglobe,through

out his right

won his empireand his masteryin war. And stretching

he bids the barbarians

hand towardthe east, and spreadinghis fingers,

and advanceno further.

in thoseregionsto remainin theirowncountry,

The significanceof the statue in the triumphalcycle is clear

fromProcopius'description. Grabar in his discussionof the monument5 emphasizesthe symbolismof the crossmountedon the globe

which the emperorcarried; this was the oravpoS VMKOWOL6s, the sign

which, from the time of Constantine,had given victory to the

emperor.

The most intriguingaspect of the statue is that it is said to

representthe emperoras Achilles. Grabar points out 6 that the

oftheemperorherewithAchillesreflectsthe tendency,

identification

which was a natural one at Byzantium (especially in view of the

conventionsof rhetoricand the panegyric),to illustratethe valor

of the princeby comparinghimwiththe heroesof antiquity. This

is of course the chief point, but the statue still suggests further

questions. Why the choice of this particular Greek hero? Did

this characterreside in the formand appearance of the statue, or

was it the personalityand historyof Achilles,ratherthan the costume alone, which gave the statue its significance? What iconographic source or traditionwould be representedby the choice of

this guise fora statue of the emperor? And did Justinianhimself

ever actually appear in this fashion,or was he representedin this

way only in the statue? Answersto some of these questions have

been offeredby G. Rodenwaldt (whose workon this point was not

utilized by Grabar). There remains,in addition, a literarytext,

unknownto both of these scholars,whichprovidesa notable backgroundforthe monumentand enables us to understandits origin

a littlebetter.

Firsc we may look at Rodenwaldt's conclusions. He examines

the statue in a review of the ancient "Renaissances" and their

character.7 The mode of expression common to each of these

renaissancesis theconsciousadoption,by an age ofgrowingstrength,

of classical or classicisticmodels for the representationof its own

individual nature. Such phenomena can be perceived at various

5 Op. cit. (see note 1), 46-47.

6 Op. cit., 94-95.

7 Abstract of a lecture, ArchdologischerAnzeiger (see note 3), 318-338.

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol. lxxi]

Justinianas Achilles

71

periods of Roman history,one of which is the age of Justinian.

F. Pringsheim,in an essay on "Die archaistischeTendenz Justinians,"8 finds evidence that the emperor's legal work is not

merelypurelypractical in its scope, but reflectsalso a kind of academic effortat the re-creationof antiquity. Justinian'swhole

programwas, indeed, feltin his own time to be a renovatioof the

ImperiumRomanum.9 Rodenwaldtsees indicationsofthisarchaizing tendencyin various characteristicsof the art of the period,and

one of the monumentswhich he discussesin this connectionis the

Achillesstatue. Seekinga reason forthe use of the termAchilles,

Rodenwaldtwas able to suggestonly that the statue representeda

reminiscenceof the statues of the type describedby Pliny (N.H.

34.5.10.18): Togatae effigiesantiquitus ita dicabantur. Placuere

et nudae tenenteshastam ab epheborume gymnasiisexemplaribus,

quas Achilleas vocant. Graeca res nihilvelare, at contra Romana

ac militaristhoracas addere. The connectionbetween these nude

figuresand the armed effigyof Justinianis ratherdifficultto perceive, as Rodenwaldt recognizes; he concludes, however:10 "Bei

dem oXnyta

der EL'KwcV lIsst sich kaum die Vermutung

'AXLXXEtov

vermeiden,dass hiereine unklareErinnerungan die effigies

A chilleae

des Pliniusvorliegt,obwohldiese wederMantel noch Panzer haben.

Schwerlichhat Justinianje das klassische Kosttimder Statue getragen,die Worte 'AXLXXEtS

und fpLKCOS lehrenklar die der Antike

zugewandte Idee des Kunstwerks." Apparentlythe obscurityor

uncertaintywhichwould have existed if Justinian'sstatue were a

reminiscenceof the type mentionedby Pliny would be, in Rodenwaldt's opinion,one more characteristicof the archaizingtendency

which was responsiblefor the emperor'sappearance in this guise.

The backgroundof the statue is considerablyaltered and amplifiedby an historicalepisodewhichboth Grabar and Rodenwaldt

overlooked. This occurredwhile the usurper Basiliscus occupied

the thronewhich had been abandoned by the EmperorZeno (A.D.

475-476). Basiliscus had a nephew named Armatus, a foolish

and effeminateyoung man with an unpleasant streak of cruelty.

Armatusbecame the lover of Basiliscus' wife,the Augusta Zenonis,

and she persuaded her husband to grant him high office. The

8 Studi in onore di P. Bonfante

(Milan, Treves, 1930), i.551-587, cited by Rodenwaldt.

9 Corippus, In laudem Justini 1.185ff. (Mon. Germ. Hist., Auct. Antiq., iii.122).

0 Op. cit. (see note 3), 334-335.

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

72

GlanvilleDowney

[1940

youngfopwas made magistermilitum."1This sudden advancement

to a post ofhonor,plus the moneywhichhe now had at his disposal,

elated the youth beyond all measure. By the paradoxical process

which on occasion emergesin such a character,the young man of

fashionbegan to thinkof himselfas a warriordistinguishedforhis

valor. "This delusionso obsessed him (writesCandidus, the contemporaryhistorianwho recountsthe episode) that he began to

and to ride about in

wear the costumeof Achilles (TKEV) 'AXLXXEws)

this fashionon his horse, and parade insolentlybeforethe people

in the hippodrome."12 His vanity was still furtherpuffedup

when the mob began to call him Pyrrhus;this was actually an

allusion to his rosy cheeks, but he took it as a complimentto his

courage.

The episode is a rathertrivial one, and Armatus did not long

survive the returnof Zeno to power. Yet it casts some light,not

only on this particularbit of imperialsymbolism,and Justinian's

adoptionofit,but on theway in whichsuch symbolismwas regarded

by the populace at the time. The incidentbringsfurtherproofif such were needed-that the costume or "character" of Achilles

would in such a connectionbe a symbol of braveryand courage,

and it is evidentthat this is the explanationof Justinian'sadoption

of the schema. The episode also indicatesthat the people who saw

Armatus,and found him ridiculous,were prettywell alive to the

symbolicalmeaningof such a costume;Armatus'appearance in the

dress would certainly have fallen rather flat if people had not

known,withoutbeing told, what it stood for. Candidus did not

think it necessary to explain to his readers the significanceof

the "Achilles costume"-neither did Procopius. The fact that

people foundArmatusridiculoussuggestsalso that theywould take

the emperor'sappearance in such a schemaseriously. It is evident

that they regardedsuch a schemaas peculiarlyfittedfor,and reserved to, the emperor;forif people would have been inclinedto

laugh at such symbolismin an emperoras well as in Armatus,

Justinianwould hardlyhave had himselfportrayedin this fashion

11 On the episode see J. B. Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire (London,

Macmillan, 1923), i.392; E. W. Brooks, in the Cambridge Medieval History, I (Cambridge, Univ. Press, 1911), 473; and E. Stein, Geschichtedes spdtr6mischenReiches, I:

Vom romischenzum byzantinischenStaate (Vienna, Seidel, 1928), 537.

is preserved by Suidas, s.v. 'ApaWTos = F.H.G.,

12 This fragment of Candidus

iv.117. The fragment was formerly assigned to Malchus, but it now seems more

likely that it comes from Candidus (see Bury, op. cit. [see note 11], i.392, nn. 1-2).

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol. lxxi]

Justinianas Achilles

73

(especiallysince many of the people who saw the statue must have

known about the episode of Armatus). Evidently the "Achilles

costume" was consideredto be dignifiedenough,and well enough

established as a part of the imperialsymbolism,for Justinianto

run no riskof makinghimselfridiculousby appearingin it. So, at

least, the emperorhimselfmust have thought. Thus it may be

that when people laughed at Armatustheywere laughingnot only

at his pretensionsto being a man of valor,but also at his adopting,

forthis,a costumewhichbelongedto the emperor.

Of course it is no longernecessaryto attemptto account forthe

typeof the statue ofJustinianby supposingthat it was an " unklare

Erinnerung"of the type describedby Pliny. It was the character

of Achilles ratherthan simplythe type of the statue itself,which

gave the effigy

of the emperorits significance. It mightbe claimed

that the appearance of Justinianin this guise representedmerely

an artistictradition,and that the representationof a Roman emperoras Achilleshad come to be so much of a conventionthat any

originalsymbolismhad been lost. The episode of Armatus,however, tells heavily against this view; for the significanceof the

schemaof Achilleswould have had to be verygenerallyrecognizable

when Armatus paraded himselfin his costume. Moreover,if the

symbolical significanceof the costume as a part of the imperial

regaliahad come to be forgotten,

whileat the same timethe costume

itselfcontinuedto be used simply by artistictradition,the symbolism could scarcely have gone unrecognizedafterthe publicity

whichit had receivedfromArmatus.

Armatus'effortlikewiseplaces on a different

basis the question

whetherJustinianever actually wore the costume. If, as Rodenwaldt supposed,the emperorcould scarcelyhave wornthe costume

himself,but appeared in thisfashiononlyin the statue,the erection

of the monumentmightbe taken as anothermanifestationof an

archaizing tendency. Now, however,Armatus' conduct suggests

that it is very possible that the emperorappeared in this guise on

appropriate ceremonialoccasions, for example (like Armatus) in

the hippodrome. The comic episode of the empress' young lover

need not have preventedJustinianfromusingthe costume; indeed

the experienceof seeing it wornby a pretenderlike Armatusmight

have the effect,by way of contrast,of makingthe costume,when

wornby the emperor,seem more important,and more appropriate

to the ruler.

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

74

GlanvilleDowney

[1940

While Grabar's work has made the primarysignificanceof the

statue-its officialtheologicalmeaning-clear, a word may be said

about some of the motives which lay behind the making of the

monument. One ofthethingsthatcomesto mindhereis Justinian's

vanity. Many of his acts appear to betraya personalvanitywhich

at timesseems almost childish."3 He named at least nineteencities

forhimselfand even gave his name to one of the classes of students

in the law-school. His theological activity gave him an opportunityto displayhis learning,and his habit ofdrawingup laws himselfenabled him to show his rhetoricalaccomplishments. It seems

to have been vanity, too, that was at least in some measure responsible for his decreeing in 541 that the consulshipshould no

longerbe held by anyone but the emperor;evidentlyhe was not

pleased by the thought that an officewhich was a traditional

dignityof the emperorshould be held by his subjects as well.'4

What if his setting up the Achilles statue was simply a piece of

vanity?

This mightseem to be a major factorbehindthe appearance of

the monument. But there are, of course, other elements. The

symbolismof the VictoriaAugusti and of the o-ravpOsVLKO7OLOS was

deeply rooted in the Roman state. And at the same time,it must

not be forgotten,the Roman emperorby virtue of his officewas

surroundedby a glamorand a prestigewhichscholarslivingin the

world of today, when monarchy (save in India and Japan) has

become at best a democraticinstitution,findit hard to visualize.

It is true that the emperor'sdignityand authoritywere sometimes

precarious. But when an emperor,in addition to claiming the

respectand even venerationto whichhe was traditionallyentitled,

could like Justinianpoint to achievementswhich overshadowed

those of his predecessors,his prestigemust have been enormously

increased.

The statue in another way also representsa traditionwhich

was of importancein the peculiarpoliticaland theologicalorganization of the laterempire. The imagesof the emperorswhichplayed

a central part in the old imperialcult survived,along with many

otherusages of this cult, in the Christianempire,and continuedto

13 See, for example, Diehl, op. cit. (see note 3), 19-20, and E. Stein, "Justinian,

Johannes der Kappadozier und das Ende des Konsulats," Byzantinische Zeitschriftxxx

(1929/30), 376-381.

14 This is pointed out by Stein, loc. cit. (see note 13), 380.

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol. lxxi]

Justinianas Achilles

75

forman importantelementin the emperor'sofficialcharacterand

position. The imperialstatues and imageswereof courseno longer

worshiped,but they received a venerationwhich was, in the new

circumstances,a counterpartof the old worship. The statues of

the emperors(like that of Justinian)now served to evoke and focus

a feelingwhichwas "a simplemanifestationof loyalty,and a recognitionof the divine protectionwhichgave a superhumancharacter

to the emperor'spower." 15

This leads to a final point. The word propaganda today has

unattractive and rather ludicrous connotations. Yet one must

realize that it was carriedout systematically,skilfully,and on the

whole successfullyby the Roman emperors,who needed to keep

their programsand their functionsever before the eyes of their

subjects, and had to do this with means quite differentfromthe

various devices which are available today. Much of this work

was not propaganda as it is understoodtoday, but, as has been

is bettercalled the creationof goodpointedout by Charlesworth,'6

will. The mottoeson coins, the remindersin the buildinginscriptions, the imperialimages and statues, all served to bringhome to

the people of the empirethe existenceand activitiesof theirrulers

and the benefitsand the protectionforwhich they mightlook to

them. This exploitation was not only legitimatebut necessary.

Any statue of a Roman emperor thus had a connotationand a

special significancewhich would not occur to us automatically.

And this statue of Justinian'srepresenteda part of the same traditional message fromthe emperorto his subjects. A statue such as

this was one of the ways in whichJustiniancould remindpeople of

what he had done, and could, at the same time, create the atmospherein whichhe wished his reignto be regarded. Everyonewho

saw the statue-and many people saw it everyday-would be made

to thinkof the militaryachievementsof the emperorand of what

his reign still promised. The tradition of the VictoriaAugusti

was one which would seem of great importanceto Justinian,one

which,withoutnecessarilyany feelingof antiquarianism,he would

be especiallyanxious to maintain. Tradition,then,and justifiable

pride,mightwell have outweighedany elementof vanity involved,

15 L. Brehier, "Les survivances du culte imperial a Byzance," in L. Brehier and

P. Batiffol, Les survivances du culte imperial romain (Paris, Picard, 1920), 60.

16 See M. P. Charlesworth, "The Virtues of a Roman Emperor: Propaganda

and

the Creation of Belief," Proceedings of the British Academy xxiii (1937), 20.

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

76

GlanvilleDowney

[1940

and may have been enough to save Justinianfrombeing ridiculed,

even though he may (at least accordingto some views) have deserved it.

One of the major questions in the historyof the later Roman

empireis how it was that that empire managed to maintain itself

as long as it did in the East, whileits westernhalfgave way so soon

beforethe barbarians.'7 Studies such as those of Gage and Grabar

have illuminatedthe traditionswhich played a leading part in the

continuationofthe imperialidea, and have also illustratedthe necessity of examiningthe various manifestationsof this traditionfrom

all the possible pointsof view. The statue of Justinianas Achilles

can claim an importantpart in thisstudy. It illustratesthe variety

of the factors,personaland contemporaneous,whichcould influence

the employmentof the traditional symbols, and contrariwiseit

suggeststhe way in whichthe traditionalsymbolism,the same and

yet changing,could be used to express the stamp of an individual

emperor. For the ultimatequestionis whyJustinianchose Achilles

to representhimselfand his reign. Vanity may have played its

part here,and the traditionmay have given the emperorlicence to

indulgehimselfin this respect;yet therestill remainsthe pointthat

the characterof Achilles was available forJustinianto adopt if he

chose it. In a way it mightbe said that not only did Justinian

take on the characterof Achilles,but the emperorimposed some of

his own character on Achilles. Some people at least must have

feltvery stronglythe glamorwhich resultedfromsuch a combination. Justinian must have calculated the impressionwhich the

statue would make, and he must have knownprettywell what its

effectwould be. The Romans were always a highlycomplicated

people; and when it was possible forJustinianto representhimself

as victorious ruler in some conventional guise-as he did, for

example, in the mosaics in the Chalke 18-he must have had some

carefullyconsideredreason forthe choice of Achilles.'9

17 This problem has been well stated by N. H. Baynes in a book review in the

Journal of Roman Studies XIX (1929), 226-227.

18 Cf. Grabar, op. cit. (see note 1), 55-56. 82.

19One is led to speculate whether Alexander's admiration for Achilles may not

have entered into the symbolism of the statue, or into some people's interpretation

of it. By associating himselfwith Achilles, or taking Achilles to be his representative,

or, so to speak, his hero, Justinian may have suggested (or may have been thought to

suggest) an association between himself and Alexander. Even if there was no express

intention to set up such an equation, the idea of it would be a very natural one. The

impression which the memory of Alexander made on the Roman people and the Roman

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vol. lxxi]

Justinianas Achilles

77

These thoughtsbringus roundfinallyto one aspect ofthe history

of the Roman empire which must be kept constantlyin mind,

thoughit is a questionwhichdoes not always appear in such simple

fashion as to require, and receive, direct answer. The query is,

namely, "What did the common people under the Empire expect

of their rulers,and how were they satisfied? 20 This question

must be pondered by anyone who is concernedto know why the

Empire was as successfulas it proved to be. Our statue would

seem to have some value here. The emperorand what he stood

for were familiarenough. So too was Achilles. There had for

example been a figureof the warrioramong the bronze statues in

the " Zeuxippus" at Constantinoplewhichhad been destroyedin the

fireof the Nika riot in 532. A few years previouslyChristodorus

of Thebes had writtena descriptionof it: 21 "Divine Achilles was

beardlessand not clothedin armor,but the artisthad givenhim the

gestureof brandishinga spear in his righthand and of holdinga

shield in his left. Whetted by daring courage he seemed to be

scatteringthe threateningclouds of battle, forhis eyes shone with

the genuinelightof a son of Aeacus." Emperorand hero together

would create an effectwhichwas not by any means simplya figure

of the basileusdressed up and play-acting.

emperors, and the way in which they imitated him and multiplied representations of

him, is well brought out by A. Bruhl, "Le souvenir d'Alexandre le grand et les romains,"

Melanges d'archeologie et d'histoire (Ecole franCaise de Rome) xLvII (1930), 202-221;

see also A. Alfoldi, " Insignien und Tracht der romischen Kaiser," Ro'm. Mitt. L (1935),

152-154, and Grabar (see note 1), 94-95.

20 J quote Charlesworth, loc. cit. (see note 16), 5.

Reference may also be made

here to a recent paper by the present writer, "The Pilgrim's Progress of the Byzantine

Emperor," Church History Ix (1940), 207-217. On the subject discussed there, the

reader may profitably consult an illuminating paper by A. D. Nock, "Orphism or

Popular Philosophy?", Harvard Theological Review xxxiii (1940), 301-315.

21Anth. Pal. 2.291-296, transl. of W. R. Paton in the Loeb Classical Library.

This content downloaded from 129.96.252.188 on Sat, 12 Dec 2015 14:00:12 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- MahalleDocument7 pagesMahalleddNo ratings yet

- Ancient Map of The WorldDocument8 pagesAncient Map of The WorldddNo ratings yet

- AlbaniaDocument1 pageAlbaniaddNo ratings yet

- nalbantoglu-BIRTH OF AN AESTHETIC DISCOURSE IN OTTOMAN ARCHITECTUREDocument8 pagesnalbantoglu-BIRTH OF AN AESTHETIC DISCOURSE IN OTTOMAN ARCHITECTUREddNo ratings yet

- The Encyclopedia of Ancient History - DecumanusDocument1 pageThe Encyclopedia of Ancient History - DecumanusddNo ratings yet

- Anderson 2011-Leo III and The AnemodoulionDocument14 pagesAnderson 2011-Leo III and The AnemodoulionddNo ratings yet

- Anderson 2011-Leo III and The AnemodoulionDocument14 pagesAnderson 2011-Leo III and The AnemodoulionddNo ratings yet

- Via Egnatia-EnglishDocument12 pagesVia Egnatia-EnglishddNo ratings yet

- Laurence 1994 - Modern Ideology and The Creation of Ancient Town PlanningDocument11 pagesLaurence 1994 - Modern Ideology and The Creation of Ancient Town PlanningddNo ratings yet

- Byzantine Historical Geography ProjectsDocument7 pagesByzantine Historical Geography ProjectsddNo ratings yet

- D02-02 - Ormeling-THE NAMING PROCESSDocument3 pagesD02-02 - Ormeling-THE NAMING PROCESSddNo ratings yet

- Dalziel, Nigel MacKenzie, John M - The Encyclopedia of Empire - Bulgarian Medieval Empire (First and Second)Document6 pagesDalziel, Nigel MacKenzie, John M - The Encyclopedia of Empire - Bulgarian Medieval Empire (First and Second)ddNo ratings yet

- Travel and Religion BibliographyDocument30 pagesTravel and Religion BibliographyddNo ratings yet

- D02-01 - Meiring - THE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES-1993Document19 pagesD02-01 - Meiring - THE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES-1993ddNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Catalogue of Ottoman Gardens: Nurhan AtasoyDocument3 pagesIntroduction To The Catalogue of Ottoman Gardens: Nurhan AtasoyddNo ratings yet

- Second International Conference On The Military History of The Mediterranean SeaDocument2 pagesSecond International Conference On The Military History of The Mediterranean SeaddNo ratings yet

- Fondamenti Di Urbanistica PDFDocument70 pagesFondamenti Di Urbanistica PDFddNo ratings yet

- The Encyclopedia of Ancient History - DecumanusDocument1 pageThe Encyclopedia of Ancient History - DecumanusddNo ratings yet

- Petmezas-Structure - and - Function - of - Regional CREDIT MARKETS IN THE OTTOMAN EuropeDocument36 pagesPetmezas-Structure - and - Function - of - Regional CREDIT MARKETS IN THE OTTOMAN EuropeddNo ratings yet

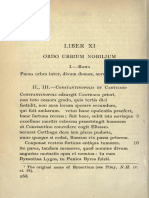

- Ausonius-Ordo Urbium NobiliumDocument18 pagesAusonius-Ordo Urbium NobiliumddNo ratings yet

- Adriana PANAITE-Roman Roads in Moesia InferiorDocument8 pagesAdriana PANAITE-Roman Roads in Moesia InferiorddNo ratings yet

- Fondamenti Di Urbanistica PDFDocument70 pagesFondamenti Di Urbanistica PDFddNo ratings yet

- Erdogan-Galata Kent Surlari Ve Koruma Öneri̇leri̇-2011Document4 pagesErdogan-Galata Kent Surlari Ve Koruma Öneri̇leri̇-2011ddNo ratings yet

- Ausonius-Ordo Urbium NobiliumDocument18 pagesAusonius-Ordo Urbium NobiliumddNo ratings yet

- Adriana PANAITE-Roman Roads in Moesia InferiorDocument8 pagesAdriana PANAITE-Roman Roads in Moesia InferiorddNo ratings yet

- Adriana PANAITE-Roman Roads in Moesia InferiorDocument8 pagesAdriana PANAITE-Roman Roads in Moesia InferiorddNo ratings yet

- F. Onal - S. Zeybekoglu-The Functional and Spatial Transformation in The Golden HornDocument10 pagesF. Onal - S. Zeybekoglu-The Functional and Spatial Transformation in The Golden HornddNo ratings yet

- Late Roman Attempts at Utopian CommunitiesDocument13 pagesLate Roman Attempts at Utopian CommunitiesddNo ratings yet

- Pages From David French-Roman Roads & Milestones of Asia Minor-Vol. 4 The Roads-Fasc. 4.1Document1 pagePages From David French-Roman Roads & Milestones of Asia Minor-Vol. 4 The Roads-Fasc. 4.1ddNo ratings yet

- Maiask-10-Lourie-syrian and Armenian Christianity in Northern MacedoniaDocument16 pagesMaiask-10-Lourie-syrian and Armenian Christianity in Northern MacedoniaddNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Greek Women Who Emigrated from Sparta to Hawai'iDocument23 pagesGreek Women Who Emigrated from Sparta to Hawai'iPanagiotis ZarifisNo ratings yet

- First Crusade, Siege of Nicaea 1: Strategic OverviewDocument17 pagesFirst Crusade, Siege of Nicaea 1: Strategic OverviewWilliam Hamblin100% (1)

- Laiou 2013, Economic Thought and Economic Life in ByzantiumDocument174 pagesLaiou 2013, Economic Thought and Economic Life in ByzantiumGuidoTorenaNo ratings yet

- Demographic StructureDocument157 pagesDemographic StructureMihai Tiuliumeanu100% (1)

- 11th Century Byzantine Clothing ConstructionDocument18 pages11th Century Byzantine Clothing ConstructionThanya AraújoNo ratings yet

- Byzantine 2nd PeriodDocument88 pagesByzantine 2nd PeriodCaius FaurNo ratings yet

- Eece Text William MillerDocument350 pagesEece Text William MillerTerry StavridisNo ratings yet

- Simulacra Pugnae. The Literery and Historical Tradition of Mock Battles in The Roman and Early Byzantine ArmyDocument53 pagesSimulacra Pugnae. The Literery and Historical Tradition of Mock Battles in The Roman and Early Byzantine ArmyMariusz MyjakNo ratings yet

- Conimbricenses. Some Questions On Signs in Aristotle (Latín-Inglés)Document218 pagesConimbricenses. Some Questions On Signs in Aristotle (Latín-Inglés)Luis Miguel Fernández-MontesNo ratings yet

- John Macdonald - Turkey and The Eastern Question PDFDocument104 pagesJohn Macdonald - Turkey and The Eastern Question PDFIgor Zdravkovic100% (1)

- Roman Empire's Rise & Fall: How Rome Built Infrastructure & GovernmentDocument25 pagesRoman Empire's Rise & Fall: How Rome Built Infrastructure & GovernmentShivani VermaNo ratings yet

- De Nicola The Chobanidsof KastamonuDocument275 pagesDe Nicola The Chobanidsof KastamonuVratislav ZervanNo ratings yet

- The Empress Irene, St. Runciman 1Document1 pageThe Empress Irene, St. Runciman 1Δέσποινα ΣκούρτηNo ratings yet

- Legal Humanism Renaissance Study of Roman LawDocument8 pagesLegal Humanism Renaissance Study of Roman LawFlo PaynoNo ratings yet

- LEONTSINI - Communication Points - Adriatic - Ionian - PORTALEE1. 3Document10 pagesLEONTSINI - Communication Points - Adriatic - Ionian - PORTALEE1. 3Μαρία ΛεοντσίνηNo ratings yet

- Serbs and Overlapping Authority of Rome and ConstantinopleDocument19 pagesSerbs and Overlapping Authority of Rome and ConstantinopleMarka Tomic Djuric100% (1)

- The Urban Evolution of Istanbul's Divanyolu StreetDocument44 pagesThe Urban Evolution of Istanbul's Divanyolu StreetVisky AgostonNo ratings yet

- Tour Around PeloponneseDocument5 pagesTour Around PeloponnesebabaNo ratings yet

- A Rural Economy in Transition Asia Minor From Late Antiquity Into The Early Middle Ages - Adam IzdebskiDocument150 pagesA Rural Economy in Transition Asia Minor From Late Antiquity Into The Early Middle Ages - Adam IzdebskiKoKetNo ratings yet

- OceanofPDF Com The Apogee Byzantium 02 John Julius NorwichDocument390 pagesOceanofPDF Com The Apogee Byzantium 02 John Julius NorwichPisica ȘtefanNo ratings yet

- DiplomasiDocument41 pagesDiplomasiNicholas DiazNo ratings yet

- A 2015 Early History AlbaniaDocument13 pagesA 2015 Early History AlbaniaCydcydNo ratings yet

- History of Architecture: Early Christian ArchitectureDocument31 pagesHistory of Architecture: Early Christian ArchitectureFilgrace EspiloyNo ratings yet

- Werewolf The Apocalypse - Tribebook - Glass Walkers (2º Edition)Document74 pagesWerewolf The Apocalypse - Tribebook - Glass Walkers (2º Edition)Vitor Augusto86% (7)

- Medieval India Xaam - inDocument25 pagesMedieval India Xaam - inkrishnaNo ratings yet

- Damascus - National Capital, Syria - Britannica Online Encyclopedia1Document8 pagesDamascus - National Capital, Syria - Britannica Online Encyclopedia1Todd HayesNo ratings yet

- Andre Du Nay - The Origins of The RumaniansDocument396 pagesAndre Du Nay - The Origins of The RumaniansMoldova.since.135980% (5)

- Art of Byzantium PDFDocument68 pagesArt of Byzantium PDFtip garesnicaNo ratings yet

- Byzantine Empire and Justinian's CodeDocument1 pageByzantine Empire and Justinian's CodeOlivia ScallyNo ratings yet

- Jim Bradbury - The Medieval Siege-Boydell Press (1992)Document479 pagesJim Bradbury - The Medieval Siege-Boydell Press (1992)Valentina EletaNo ratings yet