Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How Paternal Deprivation Harms a Child's Brain and Raises Depression Risk

Uploaded by

Shawn A. WygantOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How Paternal Deprivation Harms a Child's Brain and Raises Depression Risk

Uploaded by

Shawn A. WygantCopyright:

Available Formats

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child

Development

Shawn Wygant

Forensic Family Research

March 14, 2014

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

Introduction

Research into father-child relationships has revealed that fathers play a vital and

indispensable role in a childs emotional, cognitive, social, and physical development

(Lamb & Kelly, 2009; Allen & Daly, 2007; Cashmore, Parkinson, & Taylor, 2008; Sarkadi,

Kristiansson, Oberklaid, & Bremberg, 2008) and that their absence is associated with

causing significant harm (Bloch, Peleg, Koren, Aner, & Klein, 2007; M. Lamb & J. Lamb,

1976; Luecken & Appelhans, 2006) in the form of brain damage (Bambico, Lacoste,

Hattan, & Gobbi, 2007; Helmeke et al., 2009; Sobrinho et al., 2012), depressive disorders

(Cuplin, Heron, Araya, & Joinson, 2013; Jia, Tai, An, Zhang, & Broders, 2009), identity

problems (Lohr, Legg, Mendell, & Riemer, 1989; Lynn & Sawrey, 1959; Meerum Terwogt

et al., 2002), teenage pregnancy (Ellis et al., 2003), and aggression (Nichols, 2013).

Brain Damage from Neglect of a Childs Paternal Attachment Needs

From a child developmental perspective, the act of depriving a child of their

father is a form of child neglect (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child,

2012) since it ignores and rejects the childs basic paternal attachment needs for proper

growth and development (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005). One of these critical basic needs

comes in the form of sensory brain stimulation that is uniquely provided for by fathers

(Grossman et al., 2002). Several studies have shown that offspring who are deprived of

their father will suffer damage to the areas of the brain most responsible for making

important decisions (Bambico et al., 2013; Helmeke et al., 2009; Pinkernelle et al., 2009)

and regulating emotional reactions to ordinary stresses of daily life (Tyrka et al., 2008;

Luecken & Appelhans, 2006).

a. Bambico et al. 2013

In the Bambico et al. (2013) study, researchers demonstrated that parental

deprivation (PD) leads to abnormalities in social and reward-related behaviors that

are associated with disturbances in cortical dopamine and glutamate transmission

within the prefrontal cortex (p. 3). These neurobiological abnormalities occurred during

critical developmental periods and led to impaired social and behavioral functions in

adults (p. 16). The impairments were more pronounced in the females who exhibited a

decrease in social interaction and an increase in aggressive behavior (p. 17). The

authors believe that these observed anti-social behaviors are the result of a lack of

social play stimulation in the absence of the father (p. 17).

The import from these conclusions suggests that fathers are uniquely qualified to

teach their offspring important pro-social behaviors and that it is through the pro-social

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

father-child behaviors (play stimulation) that children develop a sufficiency of dopamine

receptors in the prefrontal cortex necessary for learning how to socialize in wide variety

of contexts. The authors also point out that the females, more than males, who were

deprived of a father developed functionally hypoactive prefrontal cortexes because of

the lack of dopamine receptors which they argue undermines both prefrontal

facilitation of prosocial behavior and inhibitory control over drug-seeking behavior (p.

19).

b. Helmeke et al. 2009

Like the Bambico et al. (2013) study, Helmeke et al. (2009) performed a set of

experiments involved with depriving rodent pups of their father and then comparing

their adult behavior with pups raised with their father. The major results of the Helmeke

et al. (2009) study showed that paternal deprivation causes delays and suppression in

the development of the orbitofrontal circuits of the forebrain as confirmed by brain

imaging analysis (p. 790). The brain imaging analysis showed retarded dendritic and

synaptic development of the apical dendrites of layer II/III pyramidal neurons in the

orbitofrontal cortex of adult fatherless animals (p. 790). The orbitofrontal cortex,

according to the authors, plays an essential role in social behaviors, choice behaviors,

decision making and impulse control in both rodents and humans (Helmeke et al.,

2009, p. 791). Another important finding from this study was the observation that the

single mothers did not compensate for the lack of paternal care and that paternal

deprivation does not increase the frequency of pup-initiated maternal contacts

(Helmeke et al., 2009, p. 793). These observations confirm that offspring of biparental

environments who are missing a father during critical periods of brain development do

not receive any compensatory stimulation from the mother.

c. Pinkernelle et al. 2009

Pinkernelle et al. (2009) make the argument that the uniqueness of paternal care

is a critical source of neonatal sensory stimulation shown to be essential for proper

brain development (p. 663). They indicate on page 671 of their report that the fatherdeprived animals showed shrunken basal dendrites in the left somatosensory cortex

leading to a reverse hemispheric asymmetry when compared with animals raised with a

father (Pinkernelle et al., 2009). Thus, paternal deprivation results in retarded

synaptic development of somatosensory circuits (Id at p. 663). This type of reduction in

left brain development has also been found in human studies involving abused children

(Teicher et al., 2003). In the Teicher et al. (2003) study, the authors reported that in 15

pediatric psychiatric inpatients with a documented history of abuse the left hemisphere

lagged substantially behind the left hemisphere of healthy controls and that in a

previous study of 24 children (7-14 years of age) with a history of trauma. the abused

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

children had attenuated frontal lobe asymmetry and smaller total brain and cerebral

volumes than controls (p. 36).

d. Tyrka et al. 2008

Both of these human and animal findings provide evidence that children who are

raised without their father suffer functional impairments to critical areas of the brain

which affects their ability to think and respond to their environment in emotionally

appropriate ways (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2012). The ability

of a child to learn how to respond to his or her environment in appropriate ways is

partially regulated by the stress system of the body which is controlled by the

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Bloch et al., 2007). In a 2008 study by Tyrka

et al. into how parental loss affects the HPA axis, it was shown that adults who were

deprived of the presence of a parent in childhood suffered damage to their

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) functioning resulting in a decreased ability to

cope with the ordinary stresses of life similar to adults who have been abused and

maltreated as children as previously reported by De Bellis et al. (1999), Teicher et al.

(2003), and Cicchetti & Toth (2005).

The Tyrka et al. (2008) study involved testing the level of cortisol responses to a

stress test in 88 healthy adults with no current Axis I psychiatric disorders (p. 1147) and

concluded that childhood parental loss was associated with alterations in adult

neuroendocrine function causing significant increases in cortisol response to the

Dex/CRH test (p. 1152). The importance of these findings demonstrates that parental

loss in childhood, whether caused from divorce or death, results in permanent changes

in the way that children as adults respond and cope with normal adverse life events such

as losing a job or losing a long-term friendship (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005).

e. Luecken & Appelhans 2006

As adults, these changes manifest as extreme or chronic physiological stress

responses (elevated and sustained levels of cortisol) to normal life events which in some

way resembles past events associated with the original feelings surrounding the parental

loss (Luecken & Appelhans, 2006; Nelson, Bos, Gunnar, & Sonuga-Barke, 2011). In the

Luecken & Appelhans (2006) study, the authors stated that these neuroendocrine

impairments contribute to physiological dysregulation at rest and chronically elevated

physiological arousal in response to stress in adults who suffered childhood parental

loss (p. 304). It is quite clear from these findings that parental deprivation causes

damage to childrens HPA functioning (Shea, Walsh, MacMillan, & Steiner, 2005) making

them less capable as adults of adapting to moderate or even low level stressful life

events (Heim, Shugart, Craighead, & Nemeroff, 2010).

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

Risk of Depression in Adolescence and Adulthood

Heim, Shugart, Craighead, & Nemeroff (2010) point out that heightened stress

sensitivity observed in adults who were neglected or abused as children is related to

persistent experiences of parental loss in childhood and leads to an increased risk of

depression (p. 676). Two important studies have shown that father absence in

childhood dramatically increases the risk for both adolescent depressive symptoms

(Culpin, Heron, Araya, Melotti, & Joinson, 2013) and adult onset major depressive

disorders (Noorikhajavi, Afghah, Dadkhah, Holakoyie, & Motamedi, 2007).

a. Culpin et al. 2013

In Culpin et al. (2013) study, 5631 children from the UK-based Avon Longitudinal

Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) were assessed for depressive symptoms at 14

years of age. For those children in the study whose fathers were absent during the first

5 years of childhood there was a significant risk of depressive symptoms at age 14

especially for girls (Culpin et al., 2013). The higher prevalence of depressive symptoms

found in adolescent girls is supported by previous studies that have shown that adult

women whose fathers were absent during early childhood (0-5) have a much higher

likelihood of depression in midlife (Maier & Lachman, 2000) and throughout the lifespan

(Personen & Raikkonen, 2012).

b. Noorikhajavi et al. 2007

In 2007, Noorikhajavi et al. examined the relationship between parental loss

under 18 and developing major depressive disorder in adulthood (p. 351). They

compared a case group of 64 adult patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital and who

met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depressive disorder with a control group of 68

non-depressive patients (Noorikhajavi et al., 2007, p. 347). Two important conclusions

were reached from this study: (1) parental loss experienced under the age of 18 is

considered as one of the risk factors in developing Major Depressive Disorder later

during the adult life and (2) that in spite of the presence of extended families and their

support. parental loss under 18 leaves certain inert major depressive effects in

persons paternally deprived (Noorikhajavi et al., 2007, pp. 352-353).

c. Slavich, Monroe, & Gotlib 2011

This type of adult-onset parental-loss related depression (Noorikhajavi et al.,

2007, p. 352) was examined in a 2011 study by Slavich, Monroe, & Gotlib (2011). They

concluded that individuals exposed to early parental loss or separation become

depressed following relatively lower levels of psychosocial stress (Slavich, Monroe, &

Gotlib, 2011, p. 1151). This association was found to be unique to stressors involving

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

interpersonal loss which the authors refer to as selective sensitization (Slavich,

Monroe, & Gotlib, 2011, p. 1151). This selective sensitization is also associated with

higher levels of cortisol found in depressed patients (Shea, Walsh, MacMillan, & Steiner,

2004) suggesting that the dysregulating effects of parental loss on the HPA axis

predisposes a child to a life-long exaggerated physiological stress response to events

related to interpersonal loss (Tyrka et al., 2008).

Identity Problems

a. Lohr, Legg, Mendell, & Riemer 1989

Losing a parent, and specifically a father, in early childhood can also become a source of

identity problems during adolescence especially for girls (Lohr, Legg, Mendell, & Riemer,

1989). According to Lohr, Legg, Mendell, & Riemer (1989) girls who are deprived of their

father during the first 5 years of life have difficulty developing a sense of femininity (p.

351). They report that this was observed in latency aged and adolescent girls whose

parents divorced during their oedipal years resulting in the emergence of the following

four maladaptive coping behavioral patterns that complicated the consolidation of

positive feminine identification:

1. Intensified separation anxiety

2. Denial and avoidance of feelings associated with loss of father

3. Identification with the lost object

4. Object hunger for males (Lohr, Legg, Mendell, & Riemer, 1989, p. 357).

With regard to the second pattern, paternally deprived girls may develop an

intense and defensive type of anger toward the absent father as an oedipal object which

can present in two potentially destructive ways: (1) fear of entering into positive oedipal

relationships with men or (2) becoming overly seductive and overly familiar (Lohr,

Legg, Mendell, & Riemer, 1989, p. 359). Both of these patterns represent a threat to any

paternally deprived adolescent girls ability to establish a healthy sense of her own

feminine identity. Therefore, the authors concluded that girls have a clear need for

ongoing involvement with their fathers to facilitate healthy psychosexual

development (Lohr, Legg, Mendell, & Riemer, 1989, p. 364).

b. Lynn & Sawrey 1959

In an older study by Lynn and Sawrey (1959), identity problems in boys were

observed when studying how young boys and girls from Norwegian sailor families

reacted to the absence of their fathers. From a sample of 80 mother-child pairs (40

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

father-absent and 40 father-present), they found that the boys in the absence of their

fathers behaved in an exaggeratedly masculine way which was considered to

compensatory (Lynn & Sawrey, 1959, p. 260). These absent father boys when given a

choice between a father-doll or mother-doll more often chose to play with the fatherdoll which the authors suggest implies strong strivings for father-identification (Lynn

& Sawrey, 1959, p. 260). This observed father-identification striving and compensatory

masculinity resulted in poor peer-adjustment behaviors (Lynn & Sawrey, 1959, p. 261).

Teenage Pregnancy & Aggression

Because of the development of identity problems observed in both boys and girls who

were paternally deprived during early childhood, some researchers have suggested that

this can lead to an increase in teenage pregnancy in girls (Ellis et al., 2003) and antisocial aggression in boys (Nichols, 2013).

a. Ellis et al. 2003

Ellis et al. (2003) conducted a longitudinal study of 762 girls (242 US & 520 New

Zealand) who were followed from age 5 through 18 and showed that father absence

was strongly associated with an elevated risk for early sexual activity and adolescent

pregnancy (p. 801). The girls in the study were classified into three groups: (1) early

onset father absent (missing at or before age 5=33%), (2) late onset father absent

(present through age 5 = 12%), and (3) father presence (present through age 13=55%).

The results indicated that approximately 60% of girls whose fathers were absent early in

life became sexually active prior to age 16 compared with 40% for fathers absent late

and 27% for fathers present through age 13 (p. 811). Similarly, girls whose fathers were

absent early became pregnant more often (34%) than fathers present (5%) and fathers

absent late (10%).

b. Nichols 2013

In the Nichols (2013) study, the researchers discovered that when young rodents

were deprived of a parent it induced hyperactivity of the HPA axis in both males and

females however this led to more aggression in the males and reduced aggression in

the females. These findings tend to support the hypothesis that with families who raise

their offspring in biparental environments, parental loss is experienced differently by

males and females (Noorikhajavi et al., 2007; Pinkernelle et al., 2009; Sobrinho et al.,

2012). In this last study by Sobrinho et al. (2012), it is interesting to note that paternal

deprivation for girls prior to adolescence was found to significantly increase their risk of

developing pituitary adenomas in adulthood and that this risk was associated with

persistent and sustained HPA hyperactivity in reaction to parental loss (OConnor,

Halloran, & Shanahan, 2000).

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

Forensic Application of Paternal Deprivation Research

Within the context of applying the foregoing paternal deprivation research to

legal cases that involve children who are being denied access to a father, it is important

to evaluate the developmental needs of those children using current research as a

guide. Lamb & Kelly (2009) provide some insight into this issue when they reported the

following:

Children benefit from supportive relationships with both of their parents, whether

or not those parents live together. In order to ensure that both adults become

or remain parents to their children, post-divorce parenting plans need to

encourage participation by both parents in as broad as possible an array of social

contexts on a regular basis. Brief dinners and occasional weekend visits do not

provide a broad enough or extensive enough basis for such relationships to be

fostered. at least one-third of the non-school hours should be spent with the

non-resident parent and most experts would agree that 15% (every other

weekend) is almost certainly insufficient (p. 206).

These statements from Lamb & Kelly (2009) clearly indicate that children who are

only provided contact with their father every other weekend (15% of available time) are

being substantively deprived of their developmental attachment needs for the presence

of their father. These insights are the result of over 40 years of parent-child relationship

research which shows that children raised without a father are at nearly four times the

risk of needing treatment for emotional and behavioral problems including the

probability of drug and alcohol abuse, mental illness, poor educational performance and

criminal activity (Helmeke et al., 2009, p. 790). Accordingly, the minimum

developmentally appropriate threshold of time spent between a non-resident parent

and his or her children should be at least 33% (Lamb & Kelly, 2009, p. 206).

References

Allen, S., & Daly, K. (2007). The effects of father involvement: An updated research

summary of the evidence. In FIRA: Father Involvement Research Alliance. Guelph, ON:

University of Guelph. Retrieved from

http://fira.ca/cms/documents/29/Effects_of_Father_Involvement.pdf

Bambico, F. R., Lacoste, B., Hattan, P. R., & Gobbi, G. (2013). Father absence in the

monogamous California mouse impairs social behavior and modifies dopamine and

glutamate synapses in the medial prefrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, bht310, 1-44.

Retrieved from http://cusm.ca/sites/default/files/Submitted-last.pdf

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

Bloch, M., Peleg, I., Koren, D., Aner, H., & Klein, E. (2007). Long-term effects of early

parental loss due to divorce on the HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior, 51, 516-523.

Cashmore, J., Parkinson, P., & Taylor, A. (2008). Overnight stays and childrens

relationships with resident and nonresident parents after divorce. Journal of Family Issues,

29(6), 707-733.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2005). Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical

Psychology, 1, 409-438.

Cuplin, I., Heron, J., Araya, R., Melotti, R., & Joinson, C. (2013). Father absence and

depressive symptoms in adolescence: Findings from a UK cohort. Psychological Medicine,

43, 2615-2626.

De Bellis, M. D., Baum, A. S., Birmaher, B., Keshavan, M. S., Eccard, C. H., Boring, A. M.,

Jenkins, F. J., & Ryan, N. D. (1999). Developmental traumatology parts I & II: Biological

stress systems & brain development. Biological Psychiatry, 45, 1259-1284.

Ellis, B. J., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Fergusson, D.M., Horwood, J. J., Pettit, G. S., &

Woodward, L. (2003). Does father absence place daughters at special risk for early sexual

activity and teenage pregnancy? Child Development, 74(3), 801-821.

Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Fremmer-Bombik, E., Kindler, H., Scheuerer-Englisch, J.,

& Zimmermann, P. (2002). The uniqueness of the child-father attachment relationship:

Fathers sensitive and challenging play as pivotal variable in a 16-year longitudinal study.

Social Development, 11(3), 301-337.

Heim, C., Shugart, M., Craighead, W. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2010). Neurobiological and

psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychobiology,

52(7), 671-690.

Helmeke, C., Seidel, K., Poeggel, G., Bredy, T.W., Abraham, A., & Braun, K. (2009). Paternal

deprivation during infancy results in dendrite and time-specific changes of dendritic

development and spine formation in the orbitofrontal cortex of the biparental rodent

octodon degus. Neuroscience, 163, 790-798.

Jia, R., Tai, F., An, S., Zhang, X., & Broders, H. (2009). Effects of neonatal paternal

deprivation or early deprivation on anxiety and social behaviors of the adults in

mandarin voles. Behavioural Processes, 82(3), 271-278.

Kolb, B., Mychasiuk, R., Muhammad, A., Li, Y., Frost, D. O., & Gibb, R. (2012). Experience

and the developing prefrontal cortex. PNAS, 109(Suppl. 2), 17186-17193.

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

10

Lamb, M. E., & Kelly, J. B. (2009). Improving the quality of parent-child contact in

separating families with infants and young children: Empirical research foundations. In R.

M. Galazter-Levy, J. Kraus, and J. Galatzer-Levy (Eds.), The Scientific Basis of Child Custody

decisions Second Edition (pp. 187-214). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

Lamb, M. E., & Lamb, J. E. (1976). The nature and importance of the father-infant

relationship. The Family Coordinator, 25(4), 379-385.

Lohr, R., Legg, C., Mendell, A. E., & Riemer, B. S. (1989). Clinical observations on

interferences of early father absence in the achievement of femininity. Clinical Social

Work Journal, 17(4), 351-365.

Luecken, L. J., & Appelhans, B. M. (2006). Early parental loss and salivary cortisol in

young adulthood: The moderating role of family environment. Development and

Psychopathology, 18, 295-308.

Lynn, D. B., & Sawrey, W. L. (1959). The effects of father-absence on Norwegian boys

and girls. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59(2), 258-262.

Maier, E. H., & Lachman, M. E. (2000). Consequences of early parental loss and

separation for health and well-being in midlife. International Journal of Behavioral

Development, 24(2), 183-189.

Meerum Terwogt, M., Meerum Terwogt-Reijinders, C. J., & Hekken, S. M. (2002). Identity

problems related to an absent genetic father. Zeitschrift fur Familienforschung, 14, 257271.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2012). The science of neglect: The

persistent absence of responsive care disrupts the developing brain: Working paper 12.

In Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University. Retrieved from

http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/reports_and_working_papers/working_pap

ers/wp12/

Nelson, C. A., Bos, K., Gunnar, M. R., & SonugaBarke, E. J. (2011). V. The neurobiological

toll of early human deprivation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child

Development, 76(4), 127-146.

Nichols, C. (2013). Evidence for a link between early life stress and adult aggression: The

role of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. BioSciences Master Reviews, 1-8.

Retrieved from http://biologie.ens-lyon.fr/biologie/ressources/bibliographies/pdf/m112-13-biosci-reviews-clairis-n-2c-m.pdf?lang=en

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

Paternal Deprivation and its Harmful Effects on Child Development

11

Noorikhajavi, M., Afghah, S., Dadkhah, A., Holakoyie, K., & Motamedi, S. H. (2007). The

effect of parental loss under 18 on developing MDD in adult age. International Journal

of Psychiatry in Medicine, 37(3), 347-355.

OConnor, T. M., Halloran, D. J., & Shanahan, F. (2000). The stress response and the

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: From molecule to melancholia. The Quarterly

Journal of Medicine, 93, 323-333.

Personen, A., & Raikkonen, K. (2012). The lifespan consequence of early life stress.

Physiology & Behavior, 106, 722-727.

Pinkernelle, J., Abraham, A., Seidel, K., & Braun, K. (2009). Paternal deprivation induces

dendritic and synaptic changes and hemispheric asymmetry of pyramidal neurons in the

somatosensory cortex. Developmental neurobiology, 69(10), 663-673.

Sarkadi, A., Kristiansson, R., Oberklaid, F., & Bremberg, S. (2008). Fathers involvement

and childrens developmental outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies.

Acta Paediatrica, 97, 153-158.

Shea, A., Walsh, C., MacMillan, H., & Steiner, M. (2005). Child maltreatment and HPA axis

dysregulation: Relation to major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder

in females. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(2), 162-178.

Slavich, G. M., Monroe, S. M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Early parental loss and depression

history: Associations with recent life stress in major depressive disorder. Journal of

Psychiatric Research, 45(9), 1146-1152.

Sobrinho, L. G., Duarte, J. S., Paiva, I., Gomes, L., Vicente, V., & Aguiar, P. (2012). Paternal

deprivation prior to adolescence and vulnerability to pituitary adenomas. Pituitary, 15(2),

251-257.

Teicher, M. H., Andersen, S. L., Polcari, A., Anderson, C. M., Navalta, C. P., & Kim, D. M.

(2003). The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment.

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 27(1), 33-44.

Tyrka, A., Wier, L., Price, L. H., Ross, N., Anderson, G. M., Wilkinson, C.W., & Carpenter, L.

L. (2008). Childhood parental loss and adult hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function.

Biological Psychiatry, 63(12), 1147-1154.

Wygant, S. A. (March, 2014)

You might also like

- Saunders (2016) Battered Women Negative Consequences Child Custody Parental AlienationDocument25 pagesSaunders (2016) Battered Women Negative Consequences Child Custody Parental AlienationShawn A. Wygant100% (1)

- Fairy Tales and Script Drama AnalysisDocument5 pagesFairy Tales and Script Drama AnalysisAdriana Cristina SaraceanuNo ratings yet

- Custody Evaluations When There Are Allegations of Domestic Violence - Practices, Beliefs, and Recommendations of Professional EvaluatorsDocument156 pagesCustody Evaluations When There Are Allegations of Domestic Violence - Practices, Beliefs, and Recommendations of Professional EvaluatorsAnotherAnonymomNo ratings yet

- Child Maltreatment Assessment-Volume 3: Investigation, Care, and PreventionFrom EverandChild Maltreatment Assessment-Volume 3: Investigation, Care, and PreventionNo ratings yet

- Script Drama AnalysisDocument17 pagesScript Drama Analysisanagard2593No ratings yet

- Parental Alienation - EditedDocument7 pagesParental Alienation - Editedwafula stanNo ratings yet

- Toxic Stress Toolkit: For Primary Care Providers Caring For Young ChildrenDocument37 pagesToxic Stress Toolkit: For Primary Care Providers Caring For Young Childrenariny oktavianyNo ratings yet

- Get Help From San Diego Divorce AttorneyDocument6 pagesGet Help From San Diego Divorce AttorneyKelvin bettNo ratings yet

- Parental Alienation and The Courts (2002) Medico Legal JournalDocument2 pagesParental Alienation and The Courts (2002) Medico Legal JournalSiu Chen LimNo ratings yet

- Dr. Craig Childress Professional LetterDocument4 pagesDr. Craig Childress Professional Letterko_andrew9963No ratings yet

- Dallam (2016) Recommended Treatments Parental Alienation Cause Psychological Harm To Children PDFDocument11 pagesDallam (2016) Recommended Treatments Parental Alienation Cause Psychological Harm To Children PDFShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- How Should Management Be Structured British English StudentDocument7 pagesHow Should Management Be Structured British English Studentr i s uNo ratings yet

- Harman-Jennifer Prevalence of Adults Who Are The Targets of Parental Alienating Behaviors and Their ImpactDocument22 pagesHarman-Jennifer Prevalence of Adults Who Are The Targets of Parental Alienating Behaviors and Their ImpactMilos VuckovicNo ratings yet

- Bernet 2020 Five-Factor Model With Cover PageDocument16 pagesBernet 2020 Five-Factor Model With Cover PageFamily Court-CorruptionNo ratings yet

- A Random-Walk-Down-Wall-Street-Malkiel-En-2834 PDFDocument5 pagesA Random-Walk-Down-Wall-Street-Malkiel-En-2834 PDFTim100% (1)

- Elzer (2014) Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy Handbook KARNACDocument345 pagesElzer (2014) Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy Handbook KARNACShawn A. Wygant100% (2)

- Falshaw Et Al (1996) - Victim To Offender - A Review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 1 (4), 389-404 PDFDocument16 pagesFalshaw Et Al (1996) - Victim To Offender - A Review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 1 (4), 389-404 PDFShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Child Neglect: A Guide For Intervention: James M. Gaudin, JR., Ph.D. April 1993Document103 pagesChild Neglect: A Guide For Intervention: James M. Gaudin, JR., Ph.D. April 1993Anonymous GCEXEkSNo ratings yet

- Family Court Review - 2014 - Jaffe - A Presumption Against Shared Parenting For Family Court LitigantsDocument6 pagesFamily Court Review - 2014 - Jaffe - A Presumption Against Shared Parenting For Family Court LitigantssilviaNo ratings yet

- True Deceit False Love: Word Search Puzzles on Domestic Violence, Narcissistic Abuse, Parental Alienation & Intergenerational Family TraumaFrom EverandTrue Deceit False Love: Word Search Puzzles on Domestic Violence, Narcissistic Abuse, Parental Alienation & Intergenerational Family TraumaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Profile - Outline of Character PathologyDocument9 pagesPsychological Profile - Outline of Character PathologyGary FreedmanNo ratings yet

- Stupid Guy in the Midwest: Helpful Hints for Non-Custodial Dads and StepmomsFrom EverandStupid Guy in the Midwest: Helpful Hints for Non-Custodial Dads and StepmomsNo ratings yet

- Phenomenological Study of Fathers - Parental Alienation ExperienceDocument142 pagesPhenomenological Study of Fathers - Parental Alienation ExperienceIsel VarzebaNo ratings yet

- Highlights in USE OF THE MMPI IN CUSTODY CASESDocument9 pagesHighlights in USE OF THE MMPI IN CUSTODY CASESMarija OrelNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Analysis of Parental AlienationDocument110 pagesQuantitative Analysis of Parental AlienationbenidroNo ratings yet

- Swanson 2009 Parental Psychological Control - Mutually Autonomous Relationship in AdulthoodDocument52 pagesSwanson 2009 Parental Psychological Control - Mutually Autonomous Relationship in AdulthoodMaria ChrisnataliaNo ratings yet

- Federal Lawsuit in AJ Freund SlayingDocument36 pagesFederal Lawsuit in AJ Freund SlayingNational Content Desk100% (1)

- Eng - Gyermekelhelyezési Per - Szülői ElidegenítésDocument26 pagesEng - Gyermekelhelyezési Per - Szülői ElidegenítésodinNo ratings yet

- Court Upholds Joint Custody Despite Father's ViolenceDocument9 pagesCourt Upholds Joint Custody Despite Father's ViolenceAnotherAnonymomNo ratings yet

- Short Guide - The Parental Alienation SyndromeDocument3 pagesShort Guide - The Parental Alienation SyndromeSarosh BastawalaNo ratings yet

- Financial Management-Capital BudgetingDocument39 pagesFinancial Management-Capital BudgetingParamjit Sharma100% (53)

- A - Therapist's - View - of - Parental - Alienation - Syndrome - Mary Lund 1995Document8 pagesA - Therapist's - View - of - Parental - Alienation - Syndrome - Mary Lund 1995peter bishopNo ratings yet

- APA PA Is Abuse PrintedDocument6 pagesAPA PA Is Abuse PrintedFamily Court-CorruptionNo ratings yet

- Family Law Newsletter Summer 2010Document5 pagesFamily Law Newsletter Summer 2010SilenceIsOppressionNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Early Psychological Trauma On Memory FinalDocument9 pagesThe Impact of Early Psychological Trauma On Memory FinalNiloc Et NihilNo ratings yet

- Neil J. Salkind - Encyclopedia of Research Design (2010, SAGE Publications, Inc) PDFDocument1,644 pagesNeil J. Salkind - Encyclopedia of Research Design (2010, SAGE Publications, Inc) PDFMark Cervantes91% (11)

- Munchausen by Proxy: A Collaborative Approach to Investigation, Assessment and TreatmentDocument29 pagesMunchausen by Proxy: A Collaborative Approach to Investigation, Assessment and TreatmentShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- No Contactorders AbafamilylawlitigationnewsletterDocument9 pagesNo Contactorders AbafamilylawlitigationnewsletterFamily Court-CorruptionNo ratings yet

- Should Children Be Asked by The Court Who They Want To Stay With After Their ParentDocument5 pagesShould Children Be Asked by The Court Who They Want To Stay With After Their ParentAli AgralNo ratings yet

- Who Is Minding The ChildrenDocument5 pagesWho Is Minding The Childrentheplatinumlife7364100% (1)

- Lawyers, Advocacy and Child ProtectionDocument30 pagesLawyers, Advocacy and Child ProtectionBritt KingNo ratings yet

- Parenting Styles: Its Influence On Children's Emotional GrowthDocument10 pagesParenting Styles: Its Influence On Children's Emotional GrowthBAISHA BARETENo ratings yet

- Yoga Practice Guide: DR - Abhishek VermaDocument26 pagesYoga Practice Guide: DR - Abhishek VermaAmarendra Kumar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Military Divers ManualDocument30 pagesMilitary Divers ManualJohn0% (1)

- AP Psychology Review in 40 CharactersDocument83 pagesAP Psychology Review in 40 CharactersKitty chenNo ratings yet

- APPsych Chapter5 TargetsDocument3 pagesAPPsych Chapter5 TargetsDuezAPNo ratings yet

- AIRs LM Business-Finance Q1 Module-5Document25 pagesAIRs LM Business-Finance Q1 Module-5Oliver N AnchetaNo ratings yet

- The Emotionally Abused and Neglected Child: Identification, Assessment and Intervention: A Practice HandbookFrom EverandThe Emotionally Abused and Neglected Child: Identification, Assessment and Intervention: A Practice HandbookNo ratings yet

- Child and DivorceDocument15 pagesChild and DivorceShubh MahalwarNo ratings yet

- APPsych Chapter3 TargetsDocument2 pagesAPPsych Chapter3 TargetsDuezAPNo ratings yet

- Spouses vs. Dev't Corp - Interest Rate on Promissory NotesDocument2 pagesSpouses vs. Dev't Corp - Interest Rate on Promissory NotesReinQZNo ratings yet

- Interventive I - K. TommDocument11 pagesInterventive I - K. TommlocologoNo ratings yet

- Ana's StatementDocument2 pagesAna's StatementmikekvolpeNo ratings yet

- Alienação ParentalDocument20 pagesAlienação ParentalFabio RochaNo ratings yet

- Child Welfare for the Twenty-first Century: A Handbook of Practices, Policies, & ProgramsFrom EverandChild Welfare for the Twenty-first Century: A Handbook of Practices, Policies, & ProgramsNo ratings yet

- Improving the Quality of Child Custody Evaluations: A Systematic ModelFrom EverandImproving the Quality of Child Custody Evaluations: A Systematic ModelNo ratings yet

- Child Custody Evaluations - JIBC LibraryDocument2 pagesChild Custody Evaluations - JIBC Librarygeko1No ratings yet

- 04 EmotionalDocument2 pages04 EmotionalSandra Barnett CrossanNo ratings yet

- Elder AbuseDocument2 pagesElder AbuseKaran4u5229No ratings yet

- Growing Up With Parental Alcohol Abuse, Exposure To Childhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household DysfunctionDocument14 pagesGrowing Up With Parental Alcohol Abuse, Exposure To Childhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household DysfunctionAndreea PalNo ratings yet

- Build a High-Nurturance Stepfamily: A Guidebook for Co-ParentsFrom EverandBuild a High-Nurturance Stepfamily: A Guidebook for Co-ParentsNo ratings yet

- Iowa Supreme Court - 061722Document182 pagesIowa Supreme Court - 061722Washington ExaminerNo ratings yet

- Mandatory Reporting Requirements: Children: Questions Arkansas Louisiana TexasDocument14 pagesMandatory Reporting Requirements: Children: Questions Arkansas Louisiana TexasCurtis HeyenNo ratings yet

- Family Deconstructed Case Study Unit 3.odtDocument7 pagesFamily Deconstructed Case Study Unit 3.odtAnonymous FVSUnLSuG100% (1)

- Elephant EthogramDocument1 pageElephant Ethogramapi-288584576No ratings yet

- Definitions of ParentDocument15 pagesDefinitions of ParentNur Anira AsyikinNo ratings yet

- Legal Aid: The First Cut Is The DeepestDocument3 pagesLegal Aid: The First Cut Is The DeepestNatasha PhillipsNo ratings yet

- A Parenting Guidebook: The Roles of School, Family, Teachers, Religion , Community, Local, State and Federal Government in Assisting Parents with Rearing Their ChildrenFrom EverandA Parenting Guidebook: The Roles of School, Family, Teachers, Religion , Community, Local, State and Federal Government in Assisting Parents with Rearing Their ChildrenNo ratings yet

- Timeline HaleyDocument13 pagesTimeline HaleymikekvolpeNo ratings yet

- Response To KVC Motion To Dismiss Schwab LawsuitDocument26 pagesResponse To KVC Motion To Dismiss Schwab LawsuitRaymond SchwabNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument4 pagesAnnotated BibliographyIris GarciaNo ratings yet

- Parent Rights CondensedDocument2 pagesParent Rights Condensedapi-511031049No ratings yet

- Juvenile Justice Resource BookDocument65 pagesJuvenile Justice Resource BookDiane FenerNo ratings yet

- Parents... Your Hs Teens Have Been Replaced by Aliens!From EverandParents... Your Hs Teens Have Been Replaced by Aliens!No ratings yet

- Jerath (2016) Pranayamic BreathingDocument2 pagesJerath (2016) Pranayamic BreathingShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Kopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Document8 pagesKopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Shawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Wang (2013) Effects of Qigong Anxiety Depression Psychological Well-BeingDocument17 pagesWang (2013) Effects of Qigong Anxiety Depression Psychological Well-BeingShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Chow (2011) Qigong Wellness DissertationDocument353 pagesChow (2011) Qigong Wellness DissertationShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Walker (2006) Extreme Consequence Parental Alienation Syndrome Richard LohstrohDocument19 pagesWalker (2006) Extreme Consequence Parental Alienation Syndrome Richard LohstrohShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Black (1999) Doing Quantitative Research Social SciencesDocument541 pagesBlack (1999) Doing Quantitative Research Social SciencesShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Glossary 03 (Aron, 2013)Document14 pagesGlossary 03 (Aron, 2013)Shawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Osborne (2008) CH 22 Testing The Assumptions of Analysis of VarianceDocument29 pagesOsborne (2008) CH 22 Testing The Assumptions of Analysis of VarianceShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Vasilyuk (1991) The Psychology of ExperiencingDocument259 pagesVasilyuk (1991) The Psychology of ExperiencingShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Hlista v. Altevogt Court Decision on Clean Hands DoctrineDocument8 pagesHlista v. Altevogt Court Decision on Clean Hands DoctrineShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Engel (1977) Need New Medical Model Challenge BiomedicineDocument9 pagesEngel (1977) Need New Medical Model Challenge BiomedicineShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Kopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Document8 pagesKopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Shawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Kopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Document8 pagesKopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Shawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Summers (2006) Unadulterated Arrogance Autopsy of The Narcissistic Parental Alienator PDFDocument31 pagesSummers (2006) Unadulterated Arrogance Autopsy of The Narcissistic Parental Alienator PDFShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Kopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Document8 pagesKopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Shawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Shaw (2016) Commentary Examining The Use of Parental Alienation SyndromeDocument4 pagesShaw (2016) Commentary Examining The Use of Parental Alienation SyndromeShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Visser (2016) Interparental Violence Mother-Child Emotion Dialogues in Families Parental AlienationDocument22 pagesVisser (2016) Interparental Violence Mother-Child Emotion Dialogues in Families Parental AlienationShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Heitler (2018) Parental Alienation Syndrome What Is It Who Does ItDocument3 pagesHeitler (2018) Parental Alienation Syndrome What Is It Who Does ItShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Clemente (2016) When Courts Accept What Science Rejects Parental Alienation SyndromeDocument9 pagesClemente (2016) When Courts Accept What Science Rejects Parental Alienation SyndromeShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- O'Donohue (2016) Examining The Validity of Parental Alienation SyndromeDocument14 pagesO'Donohue (2016) Examining The Validity of Parental Alienation SyndromeShawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- The Impact On An Abusive Family Context On ChildhoodDocument19 pagesThe Impact On An Abusive Family Context On ChildhoodRosolimou EviNo ratings yet

- Student Worksheet 8BDocument8 pagesStudent Worksheet 8BLatomeNo ratings yet

- Catalogo 4life en InglesDocument40 pagesCatalogo 4life en InglesJordanramirezNo ratings yet

- Good Paper On Time SerisDocument15 pagesGood Paper On Time SerisNamdev UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Eric Bennett - Workshops of Empire - Stegner, Engle, and American Creative Writing During The Cold War (2015, University of Iowa Press) - Libgen - LiDocument231 pagesEric Bennett - Workshops of Empire - Stegner, Engle, and American Creative Writing During The Cold War (2015, University of Iowa Press) - Libgen - LiÖzge FındıkNo ratings yet

- 4 FIN555 Chap 4 Prings Typical Parameters For Intermediate Trend (Recovered)Document16 pages4 FIN555 Chap 4 Prings Typical Parameters For Intermediate Trend (Recovered)Najwa SulaimanNo ratings yet

- Ferret Fiasco: Archie Carr IIIDocument8 pagesFerret Fiasco: Archie Carr IIIArchie Carr III100% (1)

- Bracketing MethodsDocument13 pagesBracketing Methodsasd dsa100% (1)

- Brochure For Graduate DIploma in Railway Signalling 2019 v1.0 PDFDocument4 pagesBrochure For Graduate DIploma in Railway Signalling 2019 v1.0 PDFArun BabuNo ratings yet

- Dell Market ResearchDocument27 pagesDell Market ResearchNaved Deshmukh0% (1)

- KAMAGONGDocument2 pagesKAMAGONGjeric plumosNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet Highlights Key Hazards and ProtectionsDocument7 pagesSafety Data Sheet Highlights Key Hazards and ProtectionsOm Prakash RajNo ratings yet

- Referensi Blok 15 16Document2 pagesReferensi Blok 15 16Dela PutriNo ratings yet

- Building Materials Alia Bint Khalid 19091AA001: Q) What Are The Constituents of Paint? What AreDocument22 pagesBuilding Materials Alia Bint Khalid 19091AA001: Q) What Are The Constituents of Paint? What Arealiyah khalidNo ratings yet

- Recommender Systems Research GuideDocument28 pagesRecommender Systems Research GuideSube Singh InsanNo ratings yet

- Quatuor Pour SaxophonesDocument16 pagesQuatuor Pour Saxophoneslaura lopezNo ratings yet

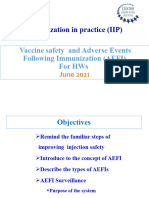

- AefiDocument38 pagesAefizedregga2No ratings yet

- The Alkazi Collection of Photography Vis PDFDocument68 pagesThe Alkazi Collection of Photography Vis PDFMochamadRizkyNoorNo ratings yet

- How to use fireworks displays at Indian weddings to create magical memoriesDocument3 pagesHow to use fireworks displays at Indian weddings to create magical memoriesChitra NarayananNo ratings yet

- Synthesis of The ArtDocument2 pagesSynthesis of The ArtPiolo Vincent Fernandez100% (1)

- DC Rebirth Reading Order 20180704Document43 pagesDC Rebirth Reading Order 20180704Michael MillerNo ratings yet

- ABAP Program Types and System FieldsDocument9 pagesABAP Program Types and System FieldsJo MallickNo ratings yet

- Final Project On Employee EngagementDocument48 pagesFinal Project On Employee Engagementanuja_solanki8903100% (1)

- Grammar Level 1 2013-2014 Part 2Document54 pagesGrammar Level 1 2013-2014 Part 2Temur SaidkhodjaevNo ratings yet