Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review

Uploaded by

Arturo EsCaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Uploaded by

Arturo EsCaCopyright:

Available Formats

382

Current Anthropology

and cognitive function. What else are we missing now, and what

will we miss in the future? Last but not least, chapter 13 carves

out a space for a new inquiry and asks what happens to our

digital content and lives upon death. Does it make sense to treat

digital assets as individual property or as part of a larger and

interconnected virtual realm that continues on in the world of

cyber ghosts long past the death of the machine?

Aging and the Digital Life Course neither offers an entirely

groundbreaking set of anthropological theories nor reframes

issues of capitalism and critical gerontology from any new

theoretical positions, which would have been nice to see in a

concluding chapter linking information and communication

technologies to various Foucauldian technologies of the body.

Research agencies, various international institutes, societies dedicated to gerontechnology, and scholars of science, technology,

and society (and even Leonardo da Vinci) have all contributed

to the pertinent issues at hand. What Aging and the Digital

Life Course manages to deliver, however, is engaging these long

standing issues in fresh and emergent contexts. There is a certain love for technology, a scientication that one can nd in

the works of Bruno Latour, here. Nonetheless, topics such as

perspectivism, technology and its application, human development, sociality, and life as an interactive eld can be found

throughout various chapters in Aging and the Digital Life

Course. More than just a commentary on the technological

products envisioned and required for addressing presbyopia,

loss of hearing, functionality issues, communication, or even

the nature of relationships in late life, this edited volume challenges us to call into question how technologies, such as web

based tools and information and communication technology,

might just reshape our conceptions and expectations of aging.

Aging and the Digital Life Course lays out some of the unintended consequences of particular technological promises and

practices and their effects on ageism and personhood. There is

value in this book, despite its unevenness.

Global Workers and the Unmaking and

Remaking of Class in the TwentyFirst

Century

Pauline Gardiner Barber

Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology, Dalhousie

University, 6135 University Avenue, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H

4R2, Canada (pgbarber@dal.ca). 28 II 16

Blood and Fire: Toward a Global Anthropology of Labor.

Edited by Sharryn Kasmir and August Carbonella. New

York: Berghahn, 2014.

There is something of a renaissance underway in the anthropology of work. While some anthropologists, including contributors to Blood and Fire, never faltered in studying the effects of global capitalism on working class lives and political

struggles, others abandoned the project. As this volume makes

Volume 57, Number 3, June 2016

abundantly clear, despite four decades of bafegab about neoliberalisms wealth generation and its trickledown effects, what

is good for capital is decidedly not and never has been good

for all, and especially not for working people. This volume

presents six examples of labor struggles and associated political violence from Colombia, the United States, India, Spain,

and Poland. Each chapter commences with a historical account

of working class struggles against powerful political coalitions.

Together they model the violent accomplishment of capitalisms making and unmaking of class relations under the guise

of neoliberalism as it unfolded in each context. It is a riveting

and sobering story conveyed through theoretically coherent

ethnographies carefully structured to represent a truly global

anthropology of labor.

The volumes title is from Marx, who evoked the image of

blood and re (1977:875) when describing the historical

movement that divorced producers from the means of production to turn them into dependent wage laborers under industrial capitalism. The title thus signals the historical depth

necessary for a truly global scholarship long absent from the

discipline. Eric Wolf (1982), cited throughout the volume, applied Marxs analysis of labor in the colonial world to challenge anthropologists on the new interrelationships and interdependencies of capitalism. Later, in the preface to a second

edition of Europe and the People Without History, Wolf saw the

need to explain why, as an anthropologist, he drew upon history and political economy to locate the peoples studied by

anthropology in the larger elds of force generated by systems of power exercised over social labor (1997:viii). By that

time, mainstream anthropology had turned inward, distracted

by postmodernism and the multiple challenges to the disciplines imperialist origins from the very people without history. However, as Carbonella and Kasmirs splendid introduction makes clear, Wolfs historical political economy, drawn

from Marx, is foundational for a truly global anthropology of

labor as the world sustains a protracted (and predictable) series of global political and economic crises.

While anthropologies of neoliberalism proliferate, and there

is more discussion of late about capitalism, this is less true

when it comes to studying class and capital (Carrier and Kalb

2015). Blood and Fire lls this gap and contributes theoretical substance to anthropologys sometimes theorylight take

on neoliberalism. Framing the discussions that follow, the introduction by the editors provides a theoretical map for a global

anthropology of labor from a Marxist perspective. It begins with

what we now recognize, in 2016, as an overly hopeful image

about expressions of political solidarity in various parts of the

world. But as the books examples reveal, protestors everywhere

confront a formidable force: capitalisms simultaneously destructive and creative accumulation strategies, pressuring labor,

its essential other, everywhere to conform or risk becoming

disposable.

In the introductions rst section, dispossession and difference, the editors outline how primitive accumulation, as a

recurrent process, relies on the production of difference among

This content downloaded from 128.110.184.042 on June 26, 2016 21:24:46 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

383

groups of workers across a global spatial scale. In their discussion of place, space, and power, they identify a dialectical

relationship between particular local struggles and the potential

for universal political ambition. Because localities are merged

and disaggregated in the production of new spaces for capital accumulation, the signicance of any local becomes an

empirical question for investigation. Readers are reminded

of Wolf s insistence on the relationship between labor made

visible through the wage relation and invisible labor outside

of that relation. Elaborated on throughout the volume, outsiders are likely to reside elsewhere across the region, the continent, or the globe. Capitalism can thus be seen to operate

through the multiplication of the proletariat and the simultaneous production of new labor and disposable populations.

Key questions for the volumes authors are (1) how has

social labor become everywhere diminished? And (2) why

has the link between the idea of labor demands and the greater

good become broken? In addressing these, the volumes chapters, taken together, make a convincing case for the renaissance of global labor studies and the multiplication of labor

perspective to replace the currently popular dualistic models,

which rely on outdated class maps in positioning people as

somehow outside of capitalism, be that as a precariat, in a

state of exception, or as excluded citizens. First up, Leslie

Gill analyzes neoliberalisms coming of age in Barrancabermeja,

Colombia. Elite class power was restored, while working class

and peasant solidarities became the target of extreme political

violence. Dispossession was enforced by a rightwing alliance

of entrepreneurs, narcoparamilitaries, state security forces,

and traditional politicians. Next, August Carbonella also depicts

collusion and cunning on the part of corporate and political

elites in their concerted attacks in the making and unmaking of

twentiethcentury Fordist working class solidarities in Maines

paper industry. Here we see how neoliberalism enhances the

geographic rescaling efforts of corporations as they dispossess

labor in some localities while creating employment elsewhere.

Central Mumbai is the setting for Judy Whiteheads discussion of class politics and spatial restructuring, which saw

the double waves of dispossession in Indias transition from

Fordism in the textile industry to exible contract work. Following mass political action during the late 1980s and 1990s,

about one million people lost their jobs, many moving to edge

cities, where the industry was reshaped to become reliant upon

contract labor. Piece workers earned onethird or onequarter

less than they did as wage employees in the former mills. From

this example, we see how exibility for capital equals dispossession of workers from livelihood security and their entrapment in the interstices of an exclusive urban geography.

Next we turn to the contours of class struggle in deindustrializing Europe, to the Spanish town of Ferrol, Galicia, birth

place of General Franco and of Pablo Iglesias, the founder of

the Spanish Socialist Party. Susana Narotzky analyzes Ferrol as

a space of extreme examples of confrontation and cooperation,

of military repression and working class mobilization. Here

again, the particularized local struggle of shipyard workers ght-

ing dispossession is contrasted with a more expansive form of

political mobilization, one that transcends class fragmentation

to become potent in working toward structural transformation.

Sharryn Kasmir considers the long history of dispossession

of US auto workers in her ethnographic analysis of the Saturn automobile factory in Spring Hill, Tennessee. Yet again,

the geographies of labor struggles for these workers reveals

how the corporation draws advantage from the localism of

US unions, as United Automobile Workers chapters act against

each other in competition for jobs. It is a competition that dissipates the potency of the union, while workers are subjected

to a major campaign about Saturns new labor relations promoting a Different kind of Company (225).

In the books nal chapter, Don Kalb explains how working

class resentment became rechanneled into rightwing populism in Central Europe. While the discussion focuses on the

hidden histories of one particular Polish pathway for labors

disenfranchisement, dispossession, and resistance, the chapter

serves as a kind of theoretical conclusion. Kalb applies the idea

of critical junctions (see Kalb 1997) to varying scales and

forms of powerstructural, tactical, and agential, taken from

Wolf (1990)to show how inequality and structural dependence can incubate a politics of fear and anger. Such ideas

add substance for critical investigation of neoliberal globalization and move us forward to a truly global Anthropology of

Labor.

References Cited

Carrier, James, and Don Kalb. 2015. Anthropologies of class: power, practice

and inequality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kalb, Don. 1997. Expanding class: power and everyday politics in industrial

communities: the Netherlands 18501950. Durham, NC: Duke University

Press.

Marx, Karl. 1977. Capital: a critique of political economy. Vol. 1. New York:

Vintage.

Wolf, Eric. 1982 (1997). Europe and the people without history. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

. 1990. Facing power: old insights, new questions. American Anthropologist 92:586596.

Parallel Worlds

Johannes Loubser

Stratum Unlimited, 10011 Carrington Lane, Johns Creek, Georgia 30022, USA, and Rock Art Research Institute, University of

the Witwatersrand, Origins Center, Yale Road, Johannesburg

2050, South Africa (jloubser@stratumunlimited.com). 28 II 16

Crow Indian Rock Art: Indigenous Perspectives and

Interpretations. By Timothy P. McCleary. Walnut Creek, CA:

Left Coast, 2016.

The book focuses on a specic portion of Plains Indian rock

art; those petroglyphs and pictographs made by the Crow people of south central Montana and north central Wyoming.

As an introduction to his book, McCleary justiably states that,

This content downloaded from 128.110.184.042 on June 26, 2016 21:24:46 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Super Diversity and Its ImplicationsDocument32 pagesSuper Diversity and Its ImplicationsArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Regimes of Value in Mexican Household Financial Practices: by Magdalena VillarrealDocument10 pagesRegimes of Value in Mexican Household Financial Practices: by Magdalena VillarrealArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- (Phronesis) Ernesto Laclau - New Reflections On The Revolution of Our Time (1990, Verso) (Dragged) PDFDocument7 pages(Phronesis) Ernesto Laclau - New Reflections On The Revolution of Our Time (1990, Verso) (Dragged) PDFArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Chapter Eight (Dragged) Copy - CompressedDocument18 pagesChapter Eight (Dragged) Copy - CompressedArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Critical Notes On Peasant Mobilization in Latin AmericaDocument22 pagesCritical Notes On Peasant Mobilization in Latin AmericaArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Womens Burden PDFDocument22 pagesWomens Burden PDFArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Womens Burden PDFDocument22 pagesWomens Burden PDFArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- SmartDocument20 pagesSmartArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Altieri 2011Document27 pagesAltieri 2011Arturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- 10 2307@2633554 PDFDocument22 pages10 2307@2633554 PDFArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Altieri 2011Document27 pagesAltieri 2011Arturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Bakunin in Naples - An AssessmentDocument25 pagesBakunin in Naples - An AssessmentArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Robert W Cox Production Power and World Order Social Forces in The Making of HistoryDocument10 pagesRobert W Cox Production Power and World Order Social Forces in The Making of HistoryArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Review 2Document22 pagesReview 2Arturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Altieri 2011Document27 pagesAltieri 2011Arturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Gmail - EU-LAC Newsletter December 2015Document9 pagesGmail - EU-LAC Newsletter December 2015Arturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Dependency, Land, Oranges in BelizeDocument19 pagesDependency, Land, Oranges in BelizeArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Legacy of BakuninDocument15 pagesThe Legacy of BakuninArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Indigenous Challenge in Latin AmericaDocument23 pagesThe Indigenous Challenge in Latin AmericaArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Michel Foucault - Truth, Power, SelfDocument4 pagesMichel Foucault - Truth, Power, SelfJames PollardNo ratings yet

- Michel Foucault - Truth, Power, SelfDocument4 pagesMichel Foucault - Truth, Power, SelfJames PollardNo ratings yet

- Kropotkin and LeninDocument9 pagesKropotkin and LeninArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Marxs Theory of Proletarian Dictatorship RevisitedDocument24 pagesMarxs Theory of Proletarian Dictatorship RevisitedArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Bakunin's Controversy With MarxDocument17 pagesBakunin's Controversy With MarxArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Anarchists in The Russain RevolutionDocument11 pagesThe Anarchists in The Russain RevolutionArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- The Anarchists in The Russain RevolutionDocument11 pagesThe Anarchists in The Russain RevolutionArturo EsCaNo ratings yet

- Levy, Carl - Gramsci and The AnarchistsDocument143 pagesLevy, Carl - Gramsci and The AnarchistsCullen Enn100% (2)

- O-L English - Model Paper - Colombo ZoneDocument6 pagesO-L English - Model Paper - Colombo ZoneJAYANI JAYAWARDHANA100% (4)

- Roll Covering Letter LathiaDocument6 pagesRoll Covering Letter LathiaPankaj PandeyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 04Document3 pagesChapter 04gebreNo ratings yet

- Pic Attack1Document13 pagesPic Attack1celiaescaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Plants Life Cycles and PartsDocument5 pagesPlants Life Cycles and PartsseemaNo ratings yet

- Nysc Editorial ManifestoDocument2 pagesNysc Editorial ManifestoSolomon Samuel AdetokunboNo ratings yet

- Self-Learning Module in General Chemistry 1 LessonDocument9 pagesSelf-Learning Module in General Chemistry 1 LessonGhaniella B. JulianNo ratings yet

- VISCOSITY CLASSIFICATION GUIDE FOR INDUSTRIAL LUBRICANTSDocument8 pagesVISCOSITY CLASSIFICATION GUIDE FOR INDUSTRIAL LUBRICANTSFrancisco TipanNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Help DocumentDocument2 pagesCase Study - Help DocumentRahNo ratings yet

- Hercules SegersDocument15 pagesHercules SegerssuneelaamjadNo ratings yet

- 3240-B0 Programmable Logic Controller (SIEMENS ET200S IM151-8)Document7 pages3240-B0 Programmable Logic Controller (SIEMENS ET200S IM151-8)alexandre jose dos santosNo ratings yet

- 50hz Sine PWM Using Tms320f2812 DSPDocument10 pages50hz Sine PWM Using Tms320f2812 DSPsivananda11No ratings yet

- Reaction CalorimetryDocument7 pagesReaction CalorimetrySankar Adhikari100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Structural - Analysis - Skid A4401 PDFDocument94 pagesStructural - Analysis - Skid A4401 PDFMohammed Saleem Syed Khader100% (1)

- Drupal 8 User GuideDocument224 pagesDrupal 8 User Guideibrail5No ratings yet

- 7 Equity Futures and Delta OneDocument65 pages7 Equity Futures and Delta OneBarry HeNo ratings yet

- Talon Star Trek Mod v0.2Document4 pagesTalon Star Trek Mod v0.2EdmundBlackadderIVNo ratings yet

- Batool2019 Article ANanocompositePreparedFromMagn PDFDocument10 pagesBatool2019 Article ANanocompositePreparedFromMagn PDFmazharNo ratings yet

- The Collected Letters of Flann O'BrienDocument640 pagesThe Collected Letters of Flann O'BrienSean MorrisNo ratings yet

- Beyond B2 English CourseDocument1 pageBeyond B2 English Coursecarlitos_coolNo ratings yet

- Value Chain AnalysisDocument4 pagesValue Chain AnalysisnidamahNo ratings yet

- List of StateDocument5 pagesList of StatedrpauliNo ratings yet

- Conservation of Kuttichira SettlementDocument145 pagesConservation of Kuttichira SettlementSumayya Kareem100% (1)

- IS 2848 - Specition For PRT SensorDocument25 pagesIS 2848 - Specition For PRT SensorDiptee PatingeNo ratings yet

- Bonding in coordination compoundsDocument65 pagesBonding in coordination compoundsHitesh vadherNo ratings yet

- CAM TOOL Solidworks PDFDocument6 pagesCAM TOOL Solidworks PDFHussein ZeinNo ratings yet

- Hilton 5-29 Case SolutionDocument4 pagesHilton 5-29 Case SolutionPebbles RobblesNo ratings yet

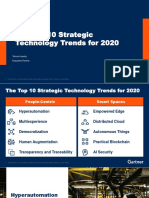

- The Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerDocument31 pagesThe Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerCarlos Stuars Echeandia CastilloNo ratings yet

- Asm Master Oral Notes - As Per New SyllabusDocument262 pagesAsm Master Oral Notes - As Per New Syllabusshanti prakhar100% (1)

- Costos estándar clase viernesDocument9 pagesCostos estándar clase viernesSergio Yamil Cuevas CruzNo ratings yet