Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Converging Paths Classical Articulation Study and The Jazz Saxophonist

Uploaded by

Junior CelestinusOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Converging Paths Classical Articulation Study and The Jazz Saxophonist

Uploaded by

Junior CelestinusCopyright:

Available Formats

Jazz Perspectives

ISSN: 1749-4060 (Print) 1749-4079 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjaz20

Converging Paths: Classical Articulation Study and

the Jazz Saxophonist

Jeremy Trezona & Matthew Styles

To cite this article: Jeremy Trezona & Matthew Styles (2014) Converging Paths: Classical

Articulation Study and the Jazz Saxophonist, Jazz Perspectives, 8:3, 259-280, DOI:

10.1080/17494060.2015.1089580

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17494060.2015.1089580

Published online: 01 Oct 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 75

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjaz20

Download by: [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris]

Date: 11 July 2016, At: 06:36

Jazz Perspectives, 2014

Vol. 8, No. 3, 259280, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17494060.2015.1089580

Converging Paths: Classical

Articulation Study and the Jazz

Saxophonist

Jeremy Trezona and Matthew Styles

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

Introduction

In speech, articulation is critical to delivering a clear message. Not only does it provide

clarity in ones words, articulation is vital for imparting character in a conversation.

Conversation itself constitutes a form of improvisation, and as Charles Edmund

writes, The spontaneous nature of spoken conversation is analogous to that of jazz

performance.1 In a musical context, articulation may be dened as the art of note

grouping by the use of legato and staccato.2 When investigating the practical application of saxophone articulation, two indispensable components must be considered:

1) The physical process utilized to produce the articulation; and

2) The stylistic implementation of the articulation.

Overall mastery in articulation therefore cannot be achieved without prociency in

these two very unique skill sets, presenting a signicant challenge to the aspiring musician. It should be noted however, that the relationship between these components is not

entirely mutually exclusive. In short, the musicians ability to physically execute the

desired articulations will always inuence their stylistic performance. On the saxophone,

the physical process of articulating is achieved primarily through a technique known as

tonguing. As Kyle Horch writes in The Cambridge Companion to the Saxophone:

The technique is quite simple: a spot very close to, but not absolutely on, the tip of the

tongue (the same spot used when pronouncing the syllable DAH against the roof of the

mouth) touches the tip of the reed just at the moment the airow begins, and comes

away again, allowing the reed to vibrate freely during the sustain period of the note.3

With stylistic expression an indispensable component of jazz performance, one may

expect to nd a multitude of pedagogical resources available on jazz articulation. As

some scholars have pointed out, there are in fact very few resources on the subject,

and fewer still when considering those related to the saxophone.4 One telling

David Charles Edmund, The Effect of Articulation Study on Stylistic Expression in High School Musicians Jazz

Performance (Ph.D. diss., Univesity of Florida, 2009), 12.

2

Larry Teal, The Art of Saxophone Playing (Miami: Summy-Birchard Inc., 1963), 87.

3

Kyle Horch, The Mechanics of Playing the Saxophone Saxophone Technique, in The Cambridge Campanion to

the Saxophone, ed. Richard Ingham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 82.

4

Edmund, Effect , 17. Jill Sullivan, The Effects of Syllabic Articulation Instruction on Woodwind Articulation

Accuracy, Contributions to Music Education 33, no. 1 (2006): 2.

1

2015 Taylor & Francis

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

260

Converging Paths

example of this is evidenced by David Bakers widely regarded method text Jazz

Improvisation, in which (of a 126 page book) Baker dedicated less than half a page

to articulation.5 Jazz saxophonists have instead traditionally relied upon developing

articulation skills aurally,6 and whilst effective in understanding stylistic intricacies,

this method cannot directly address the placement of the tongue in the oral cavity

that can affect efciency of articulation. Many jazz educators agree that saxophonists

require more concrete direction in articulation.7

Perhaps the most daunting task of the jazz saxophonist studying articulation is to

understand the tonguing action itself. Saxophone students seem to have to approximate

the articulations as heard on jazz records and therefore may nd it problematic to accurately replicate the sounds being produced. The problem is further compounded by the

fact that the tonguing action itself is hard to explain. It can be difcult for teachers to

point to their oral cavity to explain the physical processes involved in varying articulations.8 We may note also that this problem with articulation is not likely limited to the

saxophone, and indeed prevalent throughout jazz education.9

For the jazz performer, seemingly the next reasonable step in developing articulation

technique is to investigate the instruments classical tradition. During the 1930s, 40s,

and 50s a small but prominent group of classical saxophonists established themselves

as pedagogues on the instrument.10 These included Marcel Mule, Larry Teal, Sigard

Rascher, Jean-Marie Londeix and Joseph Allard.11 Far from advocating a single

approach to articulation, many classical practitioners recommend experimenting

with differing articulation techniques to nd which is most suited to the performer

both physiologically and stylistically.12

Unlike in the jazz tradition, however, these techniques tend to be specic and well

documented. As Jean-Marie Londeix writes:

It must not be thought that the restrictive choice of types of attacks is the sole prerogative of that which we call classical music. This is not the case. Indeed, we

may note that in jazz, for example, the choice of attacks inherent to a particular

type of articulation characterizing the style is just as crucial and decisive.13

Nevertheless, the classical diction seems more rigorous. Perhaps because it is more

meticulously polished, and of an older and stricter tradition, it demands not only a

similarity of attacks in all registers of each instrument, but calls for a severely limited

David Baker, Jazz Improvisation, 2nd ed. (Van Nuys: Alfred Publishing Co. Inc., 1983).

Edmund, Effect, 8.

7

See Sullivan, Effects, 2; Edmund, Effect, 17; Also, Jeremy Trezona, Interview with George Garzone, (2012).

8

Sullivan, Effects, 2.

9

Edmund, Effects, 17.

10

McKim, Joseph Allard, 1.

11

Ibid., 1.

12

See Kenneth Douse, The Saxophone, The Instrumentalist, SeptemberOctober 1949; Glen Gillis, Spotlight on

Woodwinds: Sound Concepts for the Saxophonist (Part 2), Canadian Winds: The Journal of the Canadian Band

Association 7, no. 1 (2008): 3032; Horch, Mechanics, 82; Teal, Art, 80; George E. Waln, Saxophone Playing,

The Instrumentalist, March 1965, 76.

13

Jean-Marie Londeix, Hello! Mr. Sax, ou, Paramtres du saxophone (Paris: Alphonse Leduc & Cie, 1989), 88.

6

Jazz Perspectives

261

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

choice of attacks, codied and parsimonious (by comparison with the large number of

possible attacks available to all of the instruments together).14

In consideration of Londeixs comments, an important question arises for the jazz

performer: Can the articulation techniques advocated by classical pedagogues be

appropriately and effectively utilized in a jazz context? Many jazz saxophonists may

contend on grounds of stylistic differences that the articulation techniques of the classical diction are simply unsuitable for jazz performance, particularly when relating to

improvisation. Yet, as mentioned earlier, jazz educators continue to note a general

deciency in the articulation of saxophone students, even in tertiary levels.15 As prominent jazz saxophonist and educator George Garzone explained in an interview conducted for this paper:

I think most of my career was based off of articulationteaching these guys [jazz saxophone students] how to use it because no one really knows how to do it no one

really talked about the ne line in articulation. The proof is in listening to these

people play. Over-using articulation, or using it in the wrong placesit upsets the

rhythm of what theyre playing.16

Widely known for both his unique no-tongue approach to articulation and the long

list of saxophone luminaries that have sought his tutelage (including Seamus Blake,

Joshua Redman, Donny McCaslin and Mark Turner)17, Garzone also espouses the

importance of classical study for the jazz saxophonist. When asked about his view

on a jazz saxophonist studying classical technique, Garzone replied:

Absolutely. I think the likelihood of a saxophone player understanding jazz is going to

be much greater coming from his background in classical [music], rather than

someone who just goes straight into jazz. Its ne, you can do that [go straight

into jazz], but if youve had that discipline of studying classical you know how

intense it is and thats me.18

Given that such prominent jazz saxophonists as Michael Brecker, Kenny Garrett, Branford Marsalis, Eddie Daniels, and David Liebman have all sought classical instruction in

their careers, there is a clear precedent for the jazz saxophonist to investigate the classical tradition as a means of enhancing technical ability, particularly considering the

declining inuence of classical training in jazz education.19 This paper therefore,

seeks to investigate the articulation techniques advocated by the most prominent classical pedagogues in the eld, and assess their potential utilization in jazz performance.

14

Ibid., 88.

Scott James Zimmer, A Fiber Optic Investigation of Articulation Differences between Selected Saxophonists

Procient in both Jazz and Orchestral performance Styles (DMA diss., Arizona State University, 2002), 2425;

Joel Patrick Vanderheyden, Approaching the Classical Style: a Resource for Jazz Saxophonists (DMA diss.,

The University of Iowa, 2010), 43; Trezona, Interview.

16

Trezona, Interview.

17

George Garzone on Articulating with 8th Notes, YouTube video, 6:50, posted by DAddario Woodwinds,

November 9, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jMgyckoveRw.

18

Trezona, Interview.

19

Ibid.

15

262

Converging Paths

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

Fundamental Differences between Jazz and Classical Articulation

When compared with other orchestral instruments, the saxophone is a remarkably

recent invention. Patented in 1846 by Adolphe Sax, the saxophone had been initially

designed to combine the agility of a woodwind instrument with the power and projection

of brass.20 Despite strong interest from composers such as Berlioz and Rossini shortly

after its invention,21 the saxophone would not become a permanent xture in the orchestra, instead nding its place in the classical tradition through works specically commissioned for the instrument, along with enthusiastic adoption by a growing tide of military

and wind bands.22 It would not be until the early twentieth century that the saxophone

became popularized amongst the wider public, however early adoptions in the United

States by vaudeville acts did little to promote the true capabilities of the instrument.

For many in the early twentieth century, both in professional and public spheres, the saxophone was viewed as somewhat of a novelty instrument.23 As Larry Teal explains:

From 19151919, it was possible that a typical saxophonist might have purchased an

instrument on Thursday and by Saturday that same week made 35 cents on a vaudeville stage. The requirements for securing work as a saxophonist were low because

there were almost no examples of what the instrument was capable of.24

Although vaudeville was seen by most as merely a source of entertainment, ragtimes

early associations with both jazz and vaudeville may have contributed to those in classical circles who considered jazz as an extension of this performance style. Perhaps for a

similar reason, many classical pedagogues such as Marcel Mule viewed the popularization of the saxophone in jazz music with more than a hint of regret:

As you undoubtedly know, I have tried to prove that the saxophone, just like the

other instruments, could have its place in the classical symphony orchestra and

that it possessed all the qualities needed for it to be taken seriously, that it could

play as soloist with the piano or orchestra, just like a violin or cello.

In this, it seems to me, I have remained completely in agreement with the ideas of the

inventor, Adolphe Sax, who at the time when he introduced the saxophone, around

1840, certainly had not foreseen the coming of jazz.

I think that my conception of the saxophone is in no wise original or unusual, for it

seems to me quite normal to wish to serve the cause of music, whatever the instrument may be. Isnt this the case for the clarinet, or the trumpet, or the trombone, or

the guitar, all of which, however, are much used in jazz?25

20

Claus & Ventzke Raumburger, Karl, Saxophone, The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley

Sadie (London: Macmillan Publishers Limited, 2001), 352; Vanderheyden, Approaching, 3.

21

Michael Segell, The Devils Horn (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), 15.

22

Vanderheyden, Approaching, 3.

23

Ibid. 4.

24

Michael Eric Hester, A Study of the Saxophone Soloists Performing with the John Philip Sousa Band, 1893

1930 (DMA diss., The University of Arizona, 1995), 57.

25

Marcel Mule, The Saxophone, The Instrumentalist, March 1959.

Jazz Perspectives

263

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

Unsurprisingly, these two traditions of saxophone performance developed somewhat

independently of each other for the majority of the early to mid-twentieth century.

Whilst gures such as Marcel Mule strived to promote the saxophone as an orchestral

instrument worthy of inclusion in conservatories across Europe,26 jazz saxophone

developed almost entirely as an aural tradition with very little formalization by comparison.27 For jazz saxophonists, stylistic intricacies forged on the bandstand soon

inuenced instrumental technique, and as Stephen Duke explains, the performance

space itself may have played a key role in developing articulation style:

The conceptual difference between classical and jazz is that silent ambience that does

not exist in jazz. So when youre playing jazz, youre often playing into a microphone,

there is a drummer playing, a bass player playing, and there is always some other

sound happening. People are drinking, ordering food, and there is always noise

going on. As I tell people, one sound you will never hear at Symphony Center in

Chicago is Excuse me, may I have another drink here? You never hear that

sound, and if you do youre probably getting kicked out of there! The reason for

that is because of the silent ambience. There is an incredible amount of time,

money and research spent on the acoustics for halls that orchestras play in.

Compare that with your typical jazz club where they have to add the reverb into

the amplication. So, were not even talking about the same environment that

theyre playing in, which is another big part of how the two styles had to have

been shaped. Look at the difference in concept between an orchestra hall and a

jazz club. Now you have some idea of why the attacks and releases are so different

in each style.28

As Duke makes clear in his comments, the ambient silence of the concert hall lends

itself to a kind of technical precision that may never be fully realized if performed in

a typical jazz club. By comparison, in the same article in which he expresses regret

for the publics single-mindedness in failing to associate the saxophone with music

other than jazz, Marcel Mule expresses his own desire for the manner in which the

instrument should be performed:

Particularly, one has to avoid anything which might make it seem vulgar, one must

strive for a noble, moving sound quality, and observe the most scrupulous exactitude

in pitch. In the matter of expression, nothing must be left to chance.

The saxophonist must always seek to take his inspiration from the string instruments,

and thereby justify what a certain Paris music critic once wrote about it: the saxophone, this cello of the brasses.29

Yet for all the talk of the demands of precision in the classical genre, could a real difference continue to exist between the articulation ability of modern jazz and classical saxophonists? It should be noted of course, that since the University of North Texas

became the rst university to offer a Jazz Studies degree in 1947,30 jazz has been

26

Ibid.

Edmund, Effect, 8.

28

Vanderheyden, Approaching, 42.

29

Mule, The Saxophone.

30

Edmund, Effect, 28.

27

264

Converging Paths

widely taught in universities worldwide, becoming a popular stepping-stone in the early

stages of many young musicians careers. In the words of OMeally, Edwards, and

Grifn in the introduction to their 2004 book Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz

Studies:

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

One of the wondrous oddities of our current moment is that the best advice to a

serious jazz player in training is not to drop out and study in New Yorks nightclubs

but to attend one of the several conservatories where excellent jazz instruction, by

accomplished jazz artists, is richly available.31

Despite the changing nature of jazz education, perhaps one should not underestimate

the need for a critical reassessment, particularly in the area of articulation study. As

Scott Zimmer revealed in a 2002 study utilizing ber optics to study selective saxophonists tonguing action, clear distinctions in articulation technique between jazz and

classical styles are still prevalent:

The exploratory study suggests that, generally, more tongue surface area touches the

reed in jazz articulation than in orchestral articulation. Also, the entire tongue

appears to move in jazz articulation, while the tip moves somewhat more independently of the middle and back of the tongue in orchestral articulation.32

In short, results of the study tend to suggest that classical performers exert more independence over their tongue than their jazz-based counterparts, giving credit to both

Duke and Mules comments. As jazz educators such as George Garzone continue to

teach, an over use of the tongue when articulating can lead to jazz performers encountering serious problems with phrasing and rhythmic execution.33 According to

Garzone, failure to translate aural cues into an appropriate physical response may

form the core of this problem:

When people over-articulate, its for two reasons. The nave reason is they havent

been told that theyre over-articulating, and the even more nave reason is that

they havent realized that theyre over-articulating. Students would often come to

me not realizing they had this problem and I would ask if theyd even heard themselves playing. Often their response would be Well Ive listened to Michael

Brecker and he articulates like this to which I would reply Michael denitely

doesnt articulate like this. They hear it as a misconception. They hear it one way,

but go at it from another angle, which is not what is happening at that moment.

Thats when I started to doubt how students hear these sounds; they dont process

it the way its actually being played.34

The problems many saxophone students experience when attempting to develop

articulation technique aurally are surely compounded by a lack of printed resources

on the subject. In research conducted for this paper, the authors could nd only one

item of print material outside of university academia that specically related to jazz

31

R. OMeally, B.H. Edwards, and F.J. Grifn, eds., Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 1.

32

Zimmer, Fiber, 2425.

33

Trezona, Interview.

34

Ibid.

Jazz Perspectives

265

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

Example 1. Notated back-tonguing technique.

saxophone articulationa supplement to a 1998 volume of the Saxophone Journal,

authored by University of Kentucky professor Miles Osland. In his supplement,

Osland lists seven different phrasing examples of articulation cells being utilized over

eighth note lines. The supplement however, still does not address or clarify the technical process of tonguing, instead serving as an example of stylistic implementation. As

most jazz saxophonists could surely profess, the current state of jazz articulation education seems to revolve around the back-tonguing technique (often simply referred

to as jazz articulationsee Example 1),35 a process that involves articulating the upbeats of a given eighth note line.36

Given the multi-faceted nature of modern jazz music, a point of contention when

considering back-tonguing is the techniques ongoing relevance to modern musical

situations. In the words of George Garzone:

In a certain period in time like the 40s and 50s they were using that kind of articulation, but as time went on they got away from that. I think for the young students these

teachers never really hip them to progress, and as music moved on it went forward

but no one showed them.37

The problems students encounter when pursuing jazz saxophone articulation study

therefore may be considered twofold. Firstly, there is a lack of information compiled

on the differing implementations of jazz articulationi.e. which notes may be accented

in a given musical phrase, and secondly, there is a lack of information afforded to jazz

saxophonists on the tonguing process itself, particularly those that could be considered

unique or especially important within the jazz genre. The back-tonguing technique,

whilst vital to understanding swing based jazz music, cannot sufciently address the

deciencies in these two critical areas.

Established Approaches to Classical Articulation

Contrary to a popular assumption, there is no singular, correct method of classical

saxophone articulation, as the procedures advocated for tonguing often vary widely

between teachers and performers.38 It is vital therefore, to investigate several of the

most prominent approaches to classical articulation technique, for in the words of

Larry Teal, An expert performer will usually base his advice on the system that he

has found most successful for his personal needs.39

35

How To Execute Jazz Articulation Chris Farr, YouTube video, 4:43, posted by Andreas Eastman, August 16,

2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H8f-hp8N0aE.

36

Miles Osland, Jazz Eighth Note Phrasing Cells, Saxophone Journal 22, no. 6 (1998).

37

Trezona, Interview.

38

Sullivan, Effects, 2; Waln, Saxophone Playing.

39

Teal, Art, 79.

266

Converging Paths

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

Often referred to as the father of American saxophone, Larry Teals legacy on saxophone performance was codied with the release of his comprehensive instructional

text The Art of Saxophone Playing in 1963. As the rst full time professor of saxophone

at any American university,40 Teals text has been widely quoted and seen as highly

authoritative on the subject of saxophone techniques and performance. For the jazz

saxophonist, an engaging feature of Teals text is to consider the placement of the

tongue during the tonguing process. Teal suggests three unique placements:41

1) Tip of tongue to tip of reed

2) Slightly back of tip of tongue to tip of reed, or

3) Anchoring the tip of the tongue on the lower teeth and bending the tongue to

the tip of the reed

According to Teal, performers with a large oral cavity and short tongue will nd that

tip-to-tip tonguing is advantageous, whilst if the cavity is small and the tongue long,

the third method is likely to be preferable. The majority of players however, nd

that the best results are produced by touching the tip of the reed with the top part

of the tongue at a point slightly back from its tip.42 An important feature of Teals

methodology is the small portion of the tongue that is actually required when articulating, contrary to the overuse frequently demonstrated by jazz students.43 44 As Teal

explains, the tongue should not serve as an air valve, but instead simply prevent the

reed from vibrating.45 In this way, it matters little how much area of the tongue

makes contact with the reed, for even a small area is sufcient to regulate the reeds

vibration. In words that validate the results of Zimmers ber optic study, Teal stresses:

A correct tonguing stroke requires that the front portion of the tongue be controlled

independently of any of the other factors which make up the embouchure.46

Teal develops these fundamentals of tongue placement further by introducing three

primary syllables for saxophone tone separation: too, doo and la. Regardless

of genre, most saxophonists are likely to recognize the T syllable (e.g. too or ta)

as their primary tonguing stroke, as it is readily taught to students as a means of producing a clear, stable attack. Doo, whilst not used as extensively, allows for a softer and

more connected style, just as the pronunciation of the word indicates. The doo syllable requires that the tongue be in a slightly atter and more rounded shape at the tip,

creating a softer attack. Of the three syllables Teal prescribes however, the la syllable

seems the most elusive. As he explains:

40

Honorary Member: Laurence (Larry) Teal, North American Saxophone Alliance, http://www.saxalliance.org/

honorary-members/laurence-larry-teal.

41

Teal, Art, 79.

42

Ibid., 7980.

43

George Garzone.

44

Zimmer, Fiber,2425.

45

Teal, Art, 79.

46

Ibid., 82. Emphasis in original.

Jazz Perspectives

267

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

Example 2. Excerpt of Johnny Grifns solo on The Way You Look Tonight (starting

at 1:18), from A Blowin Session. New Jersey: Blue Note, 1957.

The la-la-la type, while seldom used, is a valuable acquisition for certain subtle

phrases. The tongue merely brushes the reed tip and the result is the lightest possible

separationthe effect is really felt rather than actually heard. It must be an extremely

delicate stroke and requires much practice to control but is used by advanced players

to artistic advantage. Some artists go so far to touch but one side of the reed.47

When considering the application of this technique in jazz performance, one can

immediately draw comparisons with the tongue muting technique employed by saxophonists of the swing era and beyond. Whilst rarely (if ever) formalized, this particular

device is evidenced extensively in the playing of saxophonists such as Sonny Rollins and

Johnny Grifn.48 In Russell Petersons account, the similarities with Teals description

are uncanny:

I tend to do lots of tongue muting as I call it. Again, no one ever taught this to me, I

just heard guys do it and started imitating. I put a bit of tongue on the corner of the

reed, so its still vibrating, but its been muted a bit. When I release my tongue, I get a

nice, fat accent.49

In the example above of Johnny Grifns solo on The Way You Look Tonight from

his lauded album A Blowin Session, Grifn employs the technique to ghost a chromatic

style passage before releasing the tongue on a chord tone on beat one of the following

bar (Example 2).50 The result is something akin to a mini explosion, as the tension built

tonally during the muted passage is released with a heavy accent at a signicant point in

the phrase, both harmonically and rhythmically.

Although the three syllables prescribed by Teal open up new tonal possibilities for

the saxophonist, one classical pedagogue, Jean-Marie Londeix, takes this syllabic

approach to articulation several steps further. In his book Hello! Mr. Sax, Ou, Paramtres Du Saxophone, Londeix identies three perceptible parts of the tone: attack, duration and ending. For Londeix, the two transitory componentsthe attack and ending,

are particularly signicant. For each of these transitory components, Londeix presents a

table containing a notated example of the articulation, a name for the technique, a

graphical representation of the sound and a suggested syllable for achieving the

desired articulation. Although there are many more subtle variations on the syllabic

approach to articulation advocated by classical pedagogues (syllables include tah, ti,

47

Ibid., 82.

Trezona, Interview.

49

Vanderheyden, Approaching, 92.

50

All examples were transcribed by the author(s) and are notated in the transposed key of the instrument.

48

268

Converging Paths

di, tu),51 one can be almost certain that to date, no other classical pedagogue has prescribed a more thorough method for approaching the process of articulation than

Londeix.

With the wide variety of approaches espoused by classical pedagogues, one may wish

to consider the validity of the aforementioned techniques in the jazz genre. The reader

should be reminded of course, about the differing objectives of the two traditions. In

the words of Larry Teal:

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

Use of the word attack for the start of a tone implies an explosive or forceful assault

which, except in isolated instances, has no place in artistic performance.52

Here is surely a key point of difference between jazz and classical articulation, yet one

standout principle that classical pedagogues seem to unanimously agree on is the lightness of the tonguing action that is required to achieve articulation efciency. In this,

saxophonists may nd a concept that is readily transferrable into jazz performance.

As Rick VanMatre explains:

There is a misconception that classical tonguing is light and jazz tonguing is heavy,

but that only applies to special accents or cutoffs in jazz. Most intermediate and

beginning jazz saxophonists need to work on getting their tongue lighter on the

reed in both jazz and classical playing. In classical music, it could be said that the

goal is to have as little of the tongue touch as little of the reed as possible; whereas

in jazz; having more of a blob of tongue touching more of the reed is probably a

good thing, but only if it can be done in an extremely light way.53

Whilst some jazz instructors, such as Garzone, would continue to point out that too

much surface area of the tongue is undesirable in jazz performance,54 lightness of tonguing stroke, a focus on tongue placement and syllabic choice appear to be the key considerations to be taken from mainstream classical pedagogy when approached from a

background of jazz performance.

Joe AllardBridging the Gap between Classical and Jazz

With almost no professional saxophone instruction available in the early twentieth

century, most of the prominent saxophone pedagogues of that time did not possess

formal university or conservatory saxophone training.55 As a result, it became

common practice for these instructors to develop their own pedagogical philosophies

that they passed on to their studentsevidenced in part by the wide variety of technical

approaches advocated on articulation. Of these pedagogues, perhaps none have had

more of a notable impact on the jazz tradition than Joseph Allard. As a performer procient in both jazz and classical styles,56 Allards unique pedagogy focused intently on

Gillis, Spotlight; Douse, The Saxophone; Waln, Saxophone Playing.

Teal, Art, 79.

53

Vanderheyden, Approaching, 111.

54

George Garzone.

55

McKim, Joseph Allard, 1.

56

Ibid., 3.

51

52

Jazz Perspectives

269

the anatomical aspects of saxophone performance. As one former student of Allard

recalls:

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

I never studied technique with Joe for a minute. Out of all the lessons I took, and I

dont know if it was 100 or more over the years, they were all just about sound production. Mostly about anatomy. Thats what Joe teaches you; constantly reminding

you about the anatomy of what goes on when youre producing a sound, whats happening to your breathing, and your posture, and your muscles, and your jaw, and the

sense that you have, the sensation in your voice box. Its just amazing.57

For this reason, Allards teachings have widely transcended genre, attracting such distinguished students as Michael Brecker, Bob Berg, David Liebman, Eddie Daniels and

Eric Dolphy.58 Harvey Pittel, a prominent classical performer and former student of

Allards, attributes practically his entire teaching methodology to Allard.59 Pittel, in

turn, has taught such luminaries as Branford Marsalis and Kenny Garrett. This

unique pedagogical approach by Allard sets his teachings apart from many other classical instructors of the time. As former student Jay Weinstein illustrates in documenting Allards teachings:

The beauty of Joes principles is that they combine the physical tools that nature has

given us with the laws of physics, as they relate to the sound production. The technical explanations are as simple as possible and you will see specic reasonings

behind the ideas. This is in sharp contrast to different schools of thought that have

no true basis other than this is the way I do it or this is what Ive found to work.60

Allard taught that articulation was an indispensable expressive device, in the same camp

as dynamics and phrasing.61 According to his methodology, the key to developing

effortless articulation technique is predicated upon the tongues position in the oral

cavity. In this, two outcomes must be achieved: rstly, the tongue must be as relaxed

as possible, and secondly, the tongue must be placed in a high position in the

mouth, allowing for ease of the tonguing process. Allard formulated this concept

based on his own study into the physiology of the oral cavity, and the natural function

of the tongue.62 Allard noted that when in a relaxed state, as in daydreaming, the

tongue is positioned high and wide in the mouth.63 In order to demonstrate this position to his students, Allard formulated a linguistic solution. In Allards words:

I usually try to get them to say something like row, row, row your boat. Now,

instead of saying o if you would say re, re, r, e. In English we only have one

e, but in French there are three. You have the eh, which is called the open e,

57

Ibid., 4.

McKim, Joseph Allard, 28.

59

Harvey Pittel Presents the Saxophone Teachings of the Master, Joe Allard, Youtube video, 2:44, posted by

Andreas Eastman, June 17, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fgsA9Rab4Ww. First in a series of videos

on Allard by Pittel.

60

Joseph Allard and Jay Weinstein, Joe Allards Saxophone and Clarinet Principles [video recording] (Van Nuys:

Backstage Pass, 1991), VHS.

61

McKim, Joseph Allard,44.

62

Ibid., 42.

63

Ibid., 42.

58

270

Converging Paths

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

and you have the ee which is called the closed e and you have what they call a

neutral vowel, uh. In the tongue there are thirty muscles going through different

contractions to shape the mouth into all the different syllables we use in the

English language. In the neutral vowel e none of these lingual muscles are used,

thats the reason its called neutral. You could actually let your tongue hang on

your bottom lipits nothing more than a glottal expression, theres no lingual

tension at all. So if you go from this uh and you take it to ru the sides of

the tongue touch in the widest part of the back and the tongue is wide as the

widest part of the arch in the mouth.64

In a term borrowed from the eld of aerodynamics, this high tongue position Allard

advocated became known as forward-coning, and crucially, the technique had

more than one immediate effect on the saxophonists performance. When comparing

past students of Allard and Pittel, such as Michael Brecker, Bob Berg, Eddie Daniels,

David Liebman, Branford Marsalis and Kenny Garrett, a common thread amongst

the performers becomes readily apparenteach musician possesses a remarkably

focused tone that is synonymous with their personal sound. In David Demseys words:

When I hear Ken [Radnofsky] and I hear Harvey [Pittel] and I hear [David] Liebman

and Mike [Brecker] and Eddie Daniels, I still hear Joe. I hear that focustheres such

a focus in the sound that you can just tell that somebody studied with Joe.65

A common analogy used to consider the effect of the forward coning technique is that

of a running garden hose; a faster stream is created when the opening is narrowed with

ones nger, just as the velocity of the airstream in the oral cavity increases as a result of

a higher tongue position. With this added velocity comes a more focused tone, and for

many, this may be an unexpected but welcome byproduct of transitioning to Allards

articulation style.

In another point of difference with other prominent pedagogues, Allard compliments his principles of tongue placement with a unique approach to syllabic articulation. In this, Allard garnered his concept from a lesson with clarinetist Gaston Hamelin.

As Allard recalls:

I remember the very rst thing Hamelin ever said after he heard me play. He thought

I was French. He said that when I released my tongue from the reed in order to

produce the sound, I did it like the Americans do. He said But you are French,

you know the difference between tu and teu. Whatever you do, dont say tu like

the Americans, but say teu.66

In the teachings of other classical pedagogues, syllabic articulation often plays a key role

in articulation uency, however rarely is such a ne distinction as tu and teu made. In

Allards method, the French vowel maintains a high tongue position, with the tip of the

tongue dropping only to the level of the upper teeth. In the English pronunciation

however, the tongue drops well below the upper teeth and creates a larger cavity at

the front of the mouth. Allards action therefore promotes a much more efcient

64

Ibid., 43.

Ibid., 28.

66

Ibid., 40.

65

Jazz Perspectives

271

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

use of the tongue, and a lighter tonguing stroke. Allard noted the greatest difculty

faced by his students, both at the New England Conservatory and in professional

circles, was to achieve lightness in the tonguing stroke.67 To this end, Allard developed

exercises that he used with students to create awareness of this problem. As Ken Radnofsky explains:

One was a long note exercise. We would begin with no tongue, get very loud and

while the note was still going on, hed have us barely articulate. We would touch

the reed as lightly as possible, so that the tongue would interrupt the vibration of

the reed without stopping it, teaching us to barely tongue. Hed have us practice it

loud so that wed learn to use a light articulation even though we were playing

loud. A lot of students tongue hard when they play loud; Joes exercise separated

that.68

In this, the objectives of both Allard and mainstream classical pedagogy are aligned. A

lightness of tonguing stroke and independence over the tongue is key to developing

overall articulation prociencya critical point of consideration for the jazz

saxophonist.

Applying Classical Techniques to Jazz Performance

In a sense, much reasoning has already been provided for the potential implementation

of classical articulation techniques into the vocabulary of the jazz saxophonist. It is

apparent, through both anecdotal and scientic evidence,69 70 that jazz saxophonists

typically face difculties with a heavy tonguing stoke, largely resulting from a lack of

information afforded to them on effective articulation technique.71 To this end, classical study may ll in the gaps of knowledge of the performer, empowering the artist in

their creative pursuit.

It should be recognized however, that classical study is not always a prerequisite to

attaining prociency in articulation technique; in fact, many highly accomplished performers would attest that their technical mastery comes in large part from dedication to

a trial and error approach to practice instead. Therefore, if a case is to be made in

favor of some form of classical training for the jazz performer, perhaps it is equally

appropriate to investigate the potential application of these classical techniques into

the jazz idiom; after all, a common view amongst jazz saxophonists seems to be that

single tonguing consecutive eighth notes does not lend itself well to the jazz genre, particularly in swing-based music. As a result, articulation study for jazz performers has

become particularly focused on the aforementioned technique of back-tonguing.

By choosing a select group of jazz saxophonists who have all sought or received classical training in their careers, and honing ones listening to consider only the articulation being performed, a number of signicant and intriguing creative devices can be

67

Ibid., 44.

Ibid., 44.

69

Zimmer, Fiber,

70

Trezona, Interview.

71

Ibid.

68

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

272

Converging Paths

Example 3. Excerpt from Michael Breckers solo (starting at 6:12) on Quartet No. 2,

Part 2, from Chick Corea. Three Quartets. Los Angeles: Warner Bros. Records, 1981.

discovered. Michael Brecker is one such musician who sought tutelage from Joe Allard,

with this having a signicant impact on his playing style for the rest of his career. In the

example above (Example 3), Brecker not only demonstrates the seamless execution of

consecutive staccato eighth note phrases over an up-tempo (240bpm) swing composition, but demonstrates the dramatic albeit effective use of this technique in a

modern swing-based composition.

As many jazz performers can attest, a tendency exists for eighth note passages to

straighten out organically as the tempo increases,72 perhaps lending themselves naturally to a more classically inuenced approach to articulation. The awless execution

displayed here by Brecker, however, challenges the notion that single tongued passages

are not suitable in jazz performance.

It is inevitable, also, that heightened articulation ability will complement the traditional back-tonguing technique widely taught in jazz education. In the transcription

on the following page (Example 4) of Branford Marsalis performing Cheek to Cheek,

what at rst may be heard by the listener as consecutive single tongued passages instead

seem to be a precisely executed variant of the back-tonguing technique.

As can be seen on the following page, this presumed HADA vocalization allows

for the separation of the eighth notes (grouped in twos) without the need to single

tongue each note. In a display of technical prowess, however, Marsalis demonstrates

his articulation facility by single tonguing consecutive eighth notes in bars 10, 18

and 19, providing a subtle contrast to the previous technique. This captivating articulation style forms arguably the most remarkable moment of this improvisation, for an

artist renowned to traverse between jazz and classical genres.

For acclaimed alto saxophonist Kenny Garrett, precise and inventive articulation has

become synonymous with his unique sound. As one critic wrote while reviewing his

2003 album Standard of Language:

72

Trezona, Interview; How To Execute Jazz Articulation.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

Jazz Perspectives

273

Example 4. Excerpt from Branford Marsalis solo (starting at 0:57) on Cheek to

Cheek, from Contemporary Jazz. New York: Columbia, 2000.

While lesser talents too often sacrice articulation in the pursuit of passion, no matter

how hard he blows (very, very hard in many instances), Garrett never compromises

tone, because he doesnt need to.73

Even when listening to the introduction of the rst trackWhat is this Thing Called

Love? (Example 5)one gets an immediate sense of the rhythmic playfulness Garrett

is able to convey through his use of precise articulation.

Garretts tendency for building rhythmic tension in his improvisation is ideally complimented by his articulation ability, itself garnered from Harvey Pittel. There could be no

clearer example of this inventiveness than Garretts performance on Like the Rose,

taken from Jeff Tain Wattss live album Detained at the Blue Note (Example 6). On

this track, Garrett closes his solo by playfully targeting a single note, demonstrating both

his skillful articulation ability and rhythmic creativity. Perhaps less of an afrmation of

the classical methodology, this excerpt still stands as a ne example of how the implementation of articulation can form the focal point of an improvisation.

As we will investigate further in the following section, George Garzone is a central

gure in this investigation into jazz saxophone articulation; his prominence as a

73

Shaun Dale, Standard of Language by Kenny Garrett, JazzReview.com, accessed November 14, 2012, http://jazzreview.com/index.php/cd-reviews/cd-reviews/bebop-hard-bop-jazz-cd-reviews/item/19798-.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

274

Converging Paths

Example 5. Kenny Garretts solo introduction on What Is This Thing Called Love?

from Standard of Language. Los Angeles: Warner Bros. Records, 2003.

performer and educator, coupled with his no-tongue approach to articulation has

been highly inuential in discouraging the heavier tonguing stroke exhibited by

many younger saxophonists. According to Garzone however, this elimination of the

tongue is simply an intermediary step towards utilizing a lighter tonguing stroke to

greater musical effect in ones performance. By removing the rigidity of the heavier

style, Garzone teaches that musical phrases are given more freedom in direction,

opening the player up to more creative possibilities in improvisation.74 When more

forceful articulation is employed however (Example 7), it stands in stark contrast

with the lighter style, and thus can be used with more purpose and dramatic intent.

What is particularly remarkable about the example above is the exceptionally broad

range of articulation that Garzone draws upon, even in the relatively short space of

sixteen bars. Right away we nd the smooth eighth note phrasing synonymous with

his no-tongue method, punctuated by a subtle use of the tongue mute in the lead74

Trezona, Interview.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

Jazz Perspectives

275

Example 6. Excerpt from Kenny Garretts solo (starting at 9:34) on Like The

Rose, from Jeff Tain Watts. Detained at the Blue Note. New York: Half Note

Records, Inc., 2004.

up to the peak of the phrase in bar 2, followed by a rapid contrast to heavier articulation

in bars 411. It should be noted however, that the tongue really only plays a secondary

role in this passage; the punchiness achieved by the lower target notes comes both

from the natural characteristics of the horn and the powerful airstream that Garzone

employs here, another hallmark of his no-tongue approach. In the nal bars of

the excerpt, the tongue mute is again used to great effect by building musical

tension up to a release at the peak of the phrase, forming a harmonic resolution (by

outlining the guide-tone harmony), as well as a signicant timbral one.

By examining these short excerpts of music and considering only the articulation

being employed by these prominent artists, one can immediately get the sense of the

vast creative palette that awaits the performer by delving deeper into the realm of

articulation study. Not only does this study have the power to improve the execution

of our desired articulations (solving many of the issues exhibited by students today),

but it may also lend itself to new and exciting creative possibilities wholly compatible

within the jazz genre. To this end, classical study has the potential to form an important

bridge to harnessing these techniques, as these jazz saxophonists at the forefront of the

art form are able to demonstrate.

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

276

Converging Paths

Example 7. Excerpt from George Garzones solo (starting at 0:47) on Stablemates,

from George Garzone. One Two Three Four. Copenhagen: Stunt Records, 2007.

George GarzoneThe No-tongue Approach to Articulation

For world-renowned jazz saxophonist George Garzone, articulation has formed a critical component of his career, both in the roles of performer and educator. Garzone has

noted several key challenges that the modern-day jazz saxophonist faces when considering articulation technique, the most prominent being a tendency to overstress the traditional back-tonguing approach:

When young players are taught, theyre taught to swing the eighth notes with the

dotted eighth and the sixteenth, so people concentrate more on the rhythm of that

sound but they never really address how the dotted eighth and sixteenth are

played. So what happens is they bypass the whole situation of trying to play them

smoothly, so when they start to play it they always end up playing it with a heavy

T, [demonstrates] TA TEE TA TEE TA TEE, so that to me is an example of overusing articulation.75

As Garzone describes, this overuse of articulation stems primarily from a heavy tonguing stroke, but also reects a lack of focus on the appropriate implementation of

articulation devices. In turn, Garzone developed a radical exercise to break students

from their habitual use of heavy articulationthe no-tongue approach:

when these young students were coming in, they were over articulating, and I

tried to think what I could do to get rid of that right from the beginning. So I just

gured OK, lets use no articulation at all. So not only did it strip them down

from heavily articulating, but I found it was really challenging even for myself,

75

Trezona, Interview.

Jazz Perspectives

277

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

because it made me realize how much of a crutch the tongue is, because the tongue

stabilized the time. I think thats one reason why people over articulate, to give solidity in their time, and not thinking or realizing what theyre doing to the sound of the

eighth notes as they go along. What I did was I would be like Ok, no articulation at

all, even eighth notes, and base the articulation and the time off of how precise you

are when you press your ngers downand thats really difcult.76

For Garzone, the implementation of the no-tongue approach brought added freedom,

as the phrases being performed were seemingly released from stylistic constraints. As

mentioned earlier, jazz articulationalso known as back-tonguing, generally

only lends itself to a very straight-ahead style of performance, borne from the swing

and bebop styles of the 30s, 40s and 50s. As a modern innovator who regularly incorporates aspects of free jazz performance in his original group The Fringe, Garzone felt

increasingly compelled to overhaul his own articulation style:

of all the heavy articulators I ever heard in my life, the worst was myself I realized I needed to get rid of the articulation, and when I did it was so intense to lose it,

but once I did I realized it allowed my playing the opportunity to be less directional,

and I could stab at whatever I wanted. I could play wider intervals, where when you

articulate, even when you play a light jazz articulation its only going to head the

direction of your line one wayand thats straight-ahead; but when you lose the

articulation completely, the possibility of playing whatever you want is right there

77

While the no-tongue approach to articulation at rst appears incongruous with the

classical techniques detailed in earlier chapters, Garzone identies this exercise as the

rst step in the jazz saxophonists overhauling of their approach to articulating on

the instrument. In fact, Garzone credits much of his awareness of articulation style

to the training he received from classical saxophonist Joe Viola in his early career:

Talking about him [Joe], his concept of how he played his instruments was so [light],

he had this feather touchand I think thats where I got it from because I never heard

anyone that had a sound like that

Being with Joe, I realize now that even the way that I play free with The Fringe is

really based off a classical background. When I listen back to it, its free and its crazy,

but theres solidity to it that I think he gave me. He would say Sure, play free and do

all of that crazy stuff, but do it this way. It gives it validity.78

Throughout this process of searching for a unique articulation style, Garzones own

investigation has led him to eventually reintroduce the tonguing action into his performance, albeit in the lightest way possible:

This whole articulating thing, if you use TA its backpressure to the reed and then a

release. So anything with a T stops the reed, shuts it down and then opens it up

again, like a mini explosion. So what I did was, I developed this syllable called

Da, which is less than T. I went from T to D, and the D was a lot less

76

Ibid.

Ibid.

78

Ibid.

77

278

Converging Paths

dynamic than the T. But then I was even able to down play the Da, to the point

where it almost wasnt there, so I would play no articulation even eighth notes to this

light Da which is probably the lightest moment of articulation that you could possibly have. Thats what Im investigating right nowthe distance between nothing and

the beginning of something.79

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

What is particularly striking about this method is its resemblance to the techniques

espoused by classical pedagogues, and in particular, Joe Allard. This precise attention

to syllabic articulation, coupled with an exceptionally light stroke of the tongue,

forms the basis of both Allards articulation technique and wider classical pedagogy.

To remind the reader of the exercise Allard prescribed:

We would begin with no tongue, get very loud and while the note was still going on,

hed have us barely articulate. We would touch the reed as lightly as possible, so that

the tongue would interrupt the vibration of the reed without stopping it, teaching us

to barely tongue. Hed have us practice it loud so that wed learn to use a light articulation even though we were playing loud.80

Although Garzone was in close proximity to Allard at various points in his career (both

taught at the New England Conservatory), it is curious to note the two never engaged in

a lesson,81 leading Garzone to develop this technique entirely independently, save for

the ongoing inuence of Joe Violas early instruction. In several ways, Garzones

arrival at a light articulation style - informed by close attention to syllabic use, represents a clear endorsement of many of the principles of classical articulation pedagogy

and their relevance to jazz saxophonists.

Conclusion

Personal technique is very different from actual technique My brother Wynton

used to say that classical music helped him to develop actual technique, as

opposed to personal technique. Branford Marsalis 82

Amongst the research presented in the preceding pages about the potential benets of

classical articulation study for the jazz saxophonist, a wider conclusion about the state

of jazz education becomes increasingly more apparent: that very little time and focus

seems to be spent addressing articulation issues by jazz educators and students alike.

Instead, many aspiring jazz saxophonists seem to rely upon a combination of the prevalent back-tonguing technique and their own intuition to guide them through the

development of their articulation style. But perhaps an over-reliance on this approach

has trained saxophone students to hear only the most rudimentary articulations in a

musical phrase, and not the numerous intricacies that exist and were employed by

the greats of the genre, past and present.

A central problem that exists then is the ability to recognize more creative possibilities with articulation, learning to hear these nuances as we are trained to hear

79

Ibid.

McKim, Joseph Allard, 44.

81

Trezona, Interview.

82

Vanderheyden, Approaching, 8384.

80

Jazz Perspectives

279

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

rhythmic and harmonic elements in a phrase, the latter of which tends to form the hallmark of jazz education. Another equally important solution to this problem is nding a

way to execute these articulations effectively, and it is in this endeavor that classical

articulation study may form an important role. If the ability to recognize more possibilities with articulation forms part of our personal technique, then learning to

execute these articulations may be thought of as our actual technique, a distinction

Branford Marsalis makes when describing his brother, Wynton. Further to this, it is

perhaps a misconception by many self-taught musicians to think about these classical

techniques as being solely in the realm of the conservatory. In fact, in many cases the

reverse may be true. In the words of George Garzone:

when I started with Joe [Viola] a lot of it was classical, because back then in the

60s, they felt you needed an understanding of how to play this instrument, rather

than saying OK, heres a iiVI, which often happens now.83

Therefore, it may be a common thread amongst formally trained musicians and their selftaught counterparts that a large degree of personal investigation is required in order to

fully grasp the wide array of techniques that pertain to their instrument. Whereas in

decades past access to this information may have posed a signicant barrier in its own

right, the reality today is that most of the principles espoused by classical pedagogues

can be discovered in books, recordings, videos, and in a multitude of resources online.

Although there may be fewer obstacles to accessing this information than ever

before, the idea of taking it upon ones self to explore technical aspects of performance

has been a common thread amongst jazz musicians for their genres entire history. As

Garzone himself recalls in one example:

Joe [Viola] never said to me Youre over articulating, but I dont think he had to,

because I gured it out on my own. When I did, because of my understanding of the classical tradition, it helped me put everything together and realize what I needed to do.84

Perhaps the worst misconception a young instrumentalist can have then is assuming

that all worthwhile aspects of technical knowledge will be imparted to them in the

course of their institutional study, as this misguided belief can distract from the

reality that a large degree of personal investigation will always underpin progress in

this art form. Although nothing said is to take away from the importance of these institutions in the development of an aspiring performer, perhaps more of an emphasis

should be made on encouraging students to uncover the kind of benecial systems

prevalent throughout the classical diction. By doing so, this exploration stands to

greatly benet the student both technically and creatively.

Abstract

This article examines the numerous challenges faced by jazz saxophonists in developing

an effective articulation technique, and investigates classical saxophone pedagogy to

Trezona, Interview.

Ibid.

83

84

Downloaded by [Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris] at 06:36 11 July 2016

280

Converging Paths

address the apparent gap in knowledge and prociency. Furthermore, the paper seeks

to expand the readers creative potential by uncovering a range of articulation techniques, many of which are borne from the classical tradition and have proved compatible with jazz styles. As will be demonstrated, numerous esteemed saxophonists such as

George Garzone, Michael Brecker, Branford Marsalis, Kenny Garrett and Eric Dolphy

have sought classical tutelage during their careers, often recognizing that the classical

diction can inspire fresh creative devices in jazz improvisation. By examining the teachings of Joe Allard, Jean-Marie Londeix, Larry Teal, Marcel Mule and others, the reader

gains an overview of the most prominent classical pedagogy in the eld, and may discover ways in which these techniques can be applied to their own jazz performance. By

considering the saxophone as a case study, this paper also provides wider implications to non-saxophonists looking to expand their technique and creative potential

by delving into the classical diction.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- CRUSADE of PRAYERS 1-170 Litany 1-6 For The Key To Paradise For DistributionDocument264 pagesCRUSADE of PRAYERS 1-170 Litany 1-6 For The Key To Paradise For DistributionJESUS IS RETURNING DURING OUR GENERATION100% (10)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Sax AltissimoDocument2 pagesSax AltissimoRafael Cordova100% (19)

- Class Homework Chapter 1Document9 pagesClass Homework Chapter 1Ela BallıoğluNo ratings yet

- Training Plan JDVP 2020 - BPP (40days)Document36 pagesTraining Plan JDVP 2020 - BPP (40days)Shallimar Alcarion100% (1)

- Case Digest For Labor Relations 2Document40 pagesCase Digest For Labor Relations 2zeigfred badanaNo ratings yet

- Method Statement Soil NailedDocument2 pagesMethod Statement Soil NailedFa DylaNo ratings yet

- Jazz Chords - Folk College 2009Document20 pagesJazz Chords - Folk College 2009Erick RamoneNo ratings yet

- CherlynDocument2 pagesCherlynJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- My Hero ProjectDocument18 pagesMy Hero ProjectJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Carl OrffDocument3 pagesCarl OrffJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Circular Breathing JornalDocument11 pagesCircular Breathing JornalJunior Celestinus100% (3)

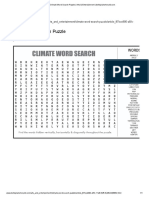

- Climate Word Search Puzzle from Belle Plaine Herald Arts SiteDocument1 pageClimate Word Search Puzzle from Belle Plaine Herald Arts SiteJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Speaking Test Form 5 2021Document5 pagesSpeaking Test Form 5 2021Junior Celestinus100% (3)

- Climate Word Search Puzzle from Belle Plaine Herald Arts SiteDocument1 pageClimate Word Search Puzzle from Belle Plaine Herald Arts SiteJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Carl OrffDocument3 pagesCarl OrffJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- 62E1Document2 pages62E1Junior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Sistem Denda Dan Bayaran Pengurusan Hal Ehwal Pengajian Siswazah (Fine Charges and Payment Related To Academic Affair Administration)Document1 pageSistem Denda Dan Bayaran Pengurusan Hal Ehwal Pengajian Siswazah (Fine Charges and Payment Related To Academic Affair Administration)Shima SenseiiNo ratings yet

- WordpuzzleDocument1 pageWordpuzzleJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- 62E1Document2 pages62E1Junior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- SBM AnnDocument1 pageSBM AnnJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- He Will Cover You With His Feathers, and Under His Wings You Will Find Refuge His Faithfulness Will Be Your Shield and Rampart. Psalm 91:4 (NIV)Document2 pagesHe Will Cover You With His Feathers, and Under His Wings You Will Find Refuge His Faithfulness Will Be Your Shield and Rampart. Psalm 91:4 (NIV)Junior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Sistem Denda Dan Bayaran Pengurusan Hal Ehwal Pengajian Siswazah (Fine Charges and Payment Related To Academic Affair Administration)Document1 pageSistem Denda Dan Bayaran Pengurusan Hal Ehwal Pengajian Siswazah (Fine Charges and Payment Related To Academic Affair Administration)Shima SenseiiNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of Saxophone Multiphonics Musical Psychophysical and Spectral AnalysisDocument13 pagesA Comparative Study of Saxophone Multiphonics Musical Psychophysical and Spectral AnalysisJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Stage PlanDocument8 pagesStage PlanJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Extended SaxDocument230 pagesExtended Saxconxin7100% (5)

- Language LinguisticsDocument49 pagesLanguage LinguisticsTijana RadisavljevicNo ratings yet

- Take Me Home & Home LyricDocument1 pageTake Me Home & Home LyricJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Eric Marienth LickDocument5 pagesEric Marienth LickJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Take Me Home & Home LyricDocument1 pageTake Me Home & Home LyricJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- Leonard BernsteinDocument19 pagesLeonard Bernsteindick100% (1)

- Animal PuzzelDocument1 pageAnimal PuzzelJunior CelestinusNo ratings yet

- AIA Layer Standards PDFDocument47 pagesAIA Layer Standards PDFdanielNo ratings yet

- Bach Invention No9 in F Minor - pdf845725625Document2 pagesBach Invention No9 in F Minor - pdf845725625ArocatrumpetNo ratings yet

- Recommender Systems Research GuideDocument28 pagesRecommender Systems Research GuideSube Singh InsanNo ratings yet

- RITL 2007 (Full Text)Document366 pagesRITL 2007 (Full Text)Institutul de Istorie și Teorie LiterarăNo ratings yet

- History of Early ChristianityDocument40 pagesHistory of Early ChristianityjeszoneNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology of GingerDocument24 pagesPharmacology of GingerArkene LevyNo ratings yet

- Westbourne Baptist Church NW CalgaryDocument4 pagesWestbourne Baptist Church NW CalgaryBonnie BaldwinNo ratings yet

- Credit Suisse AI ResearchDocument38 pagesCredit Suisse AI ResearchGianca DevinaNo ratings yet

- A StarDocument59 pagesA Starshahjaydip19912103No ratings yet

- Midnight HotelDocument7 pagesMidnight HotelAkpevweOghene PeaceNo ratings yet

- Script - TEST 5 (1st Mid-Term)Document2 pagesScript - TEST 5 (1st Mid-Term)Thu PhạmNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Sexual Reorientation What Should Clinicians and Researchers DoDocument8 pagesThe Ethics of Sexual Reorientation What Should Clinicians and Researchers DoLanny Dwi ChandraNo ratings yet

- Mechanics of Solids Unit - I: Chadalawada Ramanamma Engineering CollegeDocument1 pageMechanics of Solids Unit - I: Chadalawada Ramanamma Engineering CollegeMITTA NARESH BABUNo ratings yet

- Public Relations & Communication Theory. J.C. Skinner-1Document195 pagesPublic Relations & Communication Theory. J.C. Skinner-1Μάτζικα ντε Σπελ50% (2)

- Management of Dyspnoea - DR Yeat Choi LingDocument40 pagesManagement of Dyspnoea - DR Yeat Choi Lingmalaysianhospicecouncil6240No ratings yet

- Introduction To ResearchDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Researchapi-385504653No ratings yet

- BIS Standards in Food SectorDocument65 pagesBIS Standards in Food SectorRino John Ebenazer100% (1)

- Lecture Notes - Design of RC Structure - Day 5Document6 pagesLecture Notes - Design of RC Structure - Day 5Tapabrata2013No ratings yet

- Trends, Networks, and Critical Thinking in The 21st CenturyDocument22 pagesTrends, Networks, and Critical Thinking in The 21st CenturyGabrelle Ogayon100% (1)

- Presentation 1Document13 pagesPresentation 1lordonezNo ratings yet

- Community ResourcesDocument30 pagesCommunity Resourcesapi-242881060No ratings yet

- Study of Storm and Sewer Drains For Rajarhat (Ward No 4) in West Bengal Using Sewergems SoftwareDocument47 pagesStudy of Storm and Sewer Drains For Rajarhat (Ward No 4) in West Bengal Using Sewergems SoftwareRuben Dario Posada BNo ratings yet

- Quatuor Pour SaxophonesDocument16 pagesQuatuor Pour Saxophoneslaura lopezNo ratings yet

- INDIA'S DEFENCE FORCESDocument3 pagesINDIA'S DEFENCE FORCESJanardhan ChakliNo ratings yet

- Mobile Services Tax Invoice for Dr Reddys LaboratoriesDocument3 pagesMobile Services Tax Invoice for Dr Reddys LaboratoriesK Sree RamNo ratings yet