Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hyman v. Town of Plymouth NC, 4th Cir. (1996)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government Docs0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views4 pagesFiled: 1996-05-30

Precedential Status: Non-Precedential

Docket: 95-2865

Copyright

© Public Domain

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentFiled: 1996-05-30

Precedential Status: Non-Precedential

Docket: 95-2865

Copyright:

Public Domain

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views4 pagesHyman v. Town of Plymouth NC, 4th Cir. (1996)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsFiled: 1996-05-30

Precedential Status: Non-Precedential

Docket: 95-2865

Copyright:

Public Domain

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

UNPUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

WANDA S. HYMAN,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

TOWN OF PLYMOUTH, NORTH

CAROLINA; JARAHNEE BAILEY, Mayor

of the Town of Plymouth, North

No. 95-2865

Carolina; RICHARD HOLEMAN,

Councilman for the Town of

Plymouth, North Carolina; HARRY

HOUSE, Councilman for the Town of

Plymouth, North Carolina,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina, at Elizabeth City.

Franklin T. Dupree, Jr., Senior District Judge.

(CA-94-41-D)

Submitted: May 16, 1996

Decided: May 30, 1996

Before RUSSELL, LUTTIG, and WILLIAMS, Circuit Judges.

_________________________________________________________________

Affirmed by unpublished per curiam opinion.

_________________________________________________________________

COUNSEL

Robert Lee White, Greenville, North Carolina, for Appellant. Patricia

Lee Holland, CRANFILL, SUMNER & HARTZOG, L.L.P., Raleigh,

North Carolina, for Appellees.

Unpublished opinions are not binding precedent in this circuit. See

Local Rule 36(c).

_________________________________________________________________

OPINION

PER CURIAM:

Wanda S. Hyman appeals from the district court's order granting

summary judgment in favor of the Defendants on her 42 U.S.C.

1983 (1988) claim and her pendent state defamation claim. We

affirm.

Hyman was employed by the Town of Plymouth, North Carolina,

as its city manager from May 1993 to August 1994. On August 8,

1994, the Plymouth town council held a closed meeting after which

Hyman was advised to resign or face termination. Hyman refused to

resign and the council then voted, in an open session, to terminate

Hyman. Councilman Holeman stated in that session that Hyman

lacked the "skills and traits" necessary to solve a number of "extreme

difficulties" facing the community. This statement was published in

two local newspapers.

On September 12, 1994, approximately one month after Hyman

was fired, Councilman House made a motion during the town council

meeting to investigate "improper handling of public funds, now suspected or in the future discovered." No mention was made of Hyman

or her position. In fact, the only person even vaguely mentioned during the meeting was the town's finance officer. The local newspaper

reported that the town council had initiated an investigation "regarding possible embezzlement of town funds by a town employee," but

did not in any way refer to Hyman. One of the papers stated that

"House did not say who he suspects was responsible for the misuse

of funds."

Hyman filed this action alleging that the Defendants' actions

deprived her of due process in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and that they had defamed her based on the newspaper articles

following her termination. The district court granted summary judgment to the Defendants on both claims. Hyman appeals.

2

This court reviews the granting of summary judgment de novo.

Higgins v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 863 F.2d 1162, 1167 (4th

Cir. 1988). The party moving for summary judgment has the burden

of showing that no genuine issue of material fact exists and that it is

entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(c); Barwick

v. Celotex Corp., 736 F.2d 946, 958 (4th Cir. 1984). The party opposing the motion must come forward with some minimal facts to show

that summary judgment is not warranted. Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(e); see

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 322-23 (1986). The facts and

all reasonable inferences are to be viewed in the light most favorable

to the non-moving party. Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S.

242, 255 (1986). Hyman claimed first that she had a protected liberty

interest in maintaining her reputation in the community and that the

Defendants deprived her of that liberty interest by denying her a posttermination "name-clearing" hearing. The Supreme Court has held

that a public employee has a protected liberty interest entitling him to

notice and an opportunity to be heard where a charge is made which

damages his reputation in the community, "for example, that he had

been guilty of dishonesty, or immorality." Board of Regents v. Roth,

408 U.S. 564, 573 (1972). This court has held that"[a]llegations of

incompetence do not imply the existence of serious character defects

such as dishonesty or immorality, contemplated by Roth . . . and are

not the sort of accusations that require a hearing." Robertson v.

Rogers, 679 F.2d 1090, 1092 (4th Cir. 1982) (holding that statements

that the plaintiff had been fired for "incompetence and outside activities" did not impose on the plaintiff a stigma or disability sufficient

to implicate a constitutionally protected liberty interest); see also

Zepp v. Rehrmann, 79 F.3d 381, 388 (4th Cir. 1996).

We agree with the district court's conclusion that statements made

at the August 8 council meeting regarding Hyman's competency did

not give rise to a protected liberty interest. Nor do comments made

at the September 12 council meeting--which Hyman claims "insinuated" that she embezzled funds--give rise to a protected liberty interest because they were made after she had already been terminated.

See Siegert v. Gilley, 500 U.S. 226, 234 (1991) (no due process claim

where alleged defamation not uttered incident to employee's termination).

As to Hyman's state law claim for defamation, we find that the

record reveals no defamatory statements made by either Holeman or

3

House. Accordingly, we affirm the district court's order granting

summary judgment to the Defendants on both of Hyman's claims. We

dispense with oral argument because the facts and legal contentions

are adequately presented in the materials before the court and argument would not aid the decisional process.

AFFIRMED

4

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- An International Perspective On Cyber CrimeDocument15 pagesAn International Perspective On Cyber CrimeTariqul IslamNo ratings yet

- 10-13-2016 ECF 1438-1 USA V RYAN BUNDY - Attachment To Notice Titled Writ ProhibitioDocument15 pages10-13-2016 ECF 1438-1 USA V RYAN BUNDY - Attachment To Notice Titled Writ ProhibitioJack RyanNo ratings yet

- (English) Handbook On RSD Procedures in KoreaDocument62 pages(English) Handbook On RSD Procedures in KoreaMuhammad HamzaNo ratings yet

- 2019 Representation To Sec Jack MargieDocument1 page2019 Representation To Sec Jack MargieJenver BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Sulpico V NEDA G.R. No. 178830Document16 pagesSulpico V NEDA G.R. No. 178830Apay GrajoNo ratings yet

- Code of Ethics For Professional TeachersDocument5 pagesCode of Ethics For Professional Teachersslum_shaNo ratings yet

- People of The PH vs. Zeta PDFDocument1 pagePeople of The PH vs. Zeta PDFJulianne Ruth TanNo ratings yet

- Uposatha and Patimokkha AssembliesDocument2 pagesUposatha and Patimokkha AssembliesLong ShiNo ratings yet

- Avon Insurance PLC V CADocument7 pagesAvon Insurance PLC V CACheezy ChinNo ratings yet

- Francisco V MT DigestDocument4 pagesFrancisco V MT DigestMariel Shing100% (1)

- Architects and Engineers - A Look at Duty of Care, Causation and Contributory NegligenceDocument3 pagesArchitects and Engineers - A Look at Duty of Care, Causation and Contributory NegligenceWilliam TongNo ratings yet

- Court reinstates RTC acquittal of school official in defamation caseDocument5 pagesCourt reinstates RTC acquittal of school official in defamation caseshallyNo ratings yet

- David Barry-The SCL Delay and Disruption Protocol - 10 Years OnDocument3 pagesDavid Barry-The SCL Delay and Disruption Protocol - 10 Years OnNebojsa PavlovicNo ratings yet

- York County Court Schedule For April 25Document5 pagesYork County Court Schedule For April 25York Daily Record/Sunday NewsNo ratings yet

- Legal Aspects of Contract LawDocument62 pagesLegal Aspects of Contract LawAARCHI JAINNo ratings yet

- ERC Procedure COC ApplyDocument2 pagesERC Procedure COC Applygilgrg526No ratings yet

- Parliamentary ReformsDocument2 pagesParliamentary ReformsMp FollettNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Assets, Income and ExpenditureDocument28 pagesAffidavit of Assets, Income and ExpenditureAnubhav KathuriaNo ratings yet

- DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PD 1529 AND PUBLIC LAND ACTDocument28 pagesDIFFERENCE BETWEEN PD 1529 AND PUBLIC LAND ACTFlorz GelarzNo ratings yet

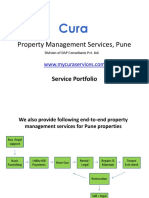

- Property ManagementDocument8 pagesProperty ManagementMyCura ServicesNo ratings yet

- The Collapse of The Muscovy Company, 1607-1620Document112 pagesThe Collapse of The Muscovy Company, 1607-1620Halim KılıçNo ratings yet

- Jails and The BJMPDocument40 pagesJails and The BJMPCinja Shidouji100% (5)

- 03 Sec 1 Tan v. MatsuraDocument11 pages03 Sec 1 Tan v. Matsurarhod leysonNo ratings yet

- Jep 24 000720603Document1 pageJep 24 000720603ivo mandantesNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Industrial Dispute Act 1947Document15 pagesCritical Analysis of Industrial Dispute Act 1947Akshat TiwaryNo ratings yet

- Southern District of Florida Local Rules (April 2002)Document176 pagesSouthern District of Florida Local Rules (April 2002)FloridaLegalBlogNo ratings yet

- Gensoc ReviewerDocument50 pagesGensoc ReviewerAdora AdoraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Quiz - Business LawDocument3 pagesChapter 2 Quiz - Business LawRayonneNo ratings yet

- Murillo vs. Bautista - No Digest YetDocument3 pagesMurillo vs. Bautista - No Digest YetBea Cape100% (1)

- Beyond Illegol Ond Is: BeyonciDocument1 pageBeyond Illegol Ond Is: BeyonciErin GamerNo ratings yet