Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Consti 1

Uploaded by

Lady BancudOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Consti 1

Uploaded by

Lady BancudCopyright:

Available Formats

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

Case Digest: The Holy See vs. Rosario, Jr.

G.R. No. 101949 01December 1994

FACTS: This petition arose from a controversy over a parcel of land

consisting of 6,000 square meters located in the Municipality of Paranaque.

Said lot was contiguous with two other lots. These lots were sold to Ramon

Licup. In view of the refusal of the squatters to vacate the lots sold, a

dispute arose as to who of the parties has the responsibility of evicting and

clearing the land of squatters. Complicating the relations of the parties was

the sale by petitioner of the lot of concern to Tropicana.

ISSUE: Whether the Holy See is immune from suit insofar as its business

relations regarding selling a lot to a private entity

RULING: As expressed in Section 2 of Article II of the 1987 Constitution,

we have adopted the generally accepted principles of International Law.

Even without this affirmation, such principles of International Law are

deemed incorporated as part of the law of the land as a condition and

consequence of our admission in the society of nations. In the present

case, if petitioner has bought and sold lands in the ordinary course of real

estate business, surely the said transaction can be categorized as an act

jure gestionis. However, petitioner has denied that the acquisition and

subsequent disposal of the lot were made for profit but claimed that it

acquired said property for the site of its mission or the Apostolic Nunciature

in the Philippines. The Holy See is immune from suit for the act of selling

the lot of concern is non-proprietary in nature. The lot was acquired by

petitioner as a donation from the Archdiocese of Manila. The donation was

made not for commercial purpose, but for the use of petitioner to construct

thereon the official place of residence of the Papal Nuncio. The decision to

transfer the property and the subsequent disposal thereof are likewise

clothed with a governmental character. Petitioner did not sell the lot for

profit or gain. It merely wanted to dispose of the same because the

squatters living thereon made it almost impossible for petitioner to use it

for the purpose of the donation.

Republic of the Philippines, petitioner, vs. Hon. Edilberto G.

Sandoval, RTC of Manila, Branch 9, Caylao et.al G. R. No. 84607,

March 19, 2003

FACTS: The doctrines of immunity of the government from suit are

expressly provided in the Constitution under Article XVI, Section 3. It is

provided that the State may not be sued without its consent. Some

instances when a suit against the State is proper are: (1) When the

Republic is sued by name; (2) When the suit is against an unincorporated

government agency; (3) When the suit is, on its face, against a

government officer but the case is such that ultimate liability will belong

not to the officer but to the government. With respect to the incident that

happened in Mendiola on January 22, 1987 that befell twelve rallyists, the

case filed against the military officers was dismissed by the lower court.

The defendants were held liable but it would not result in financial

responsibility to the government. The petitioner (Caylao Group) filed a suit

against the State that for them the State has waived its immunity when

the Mendiola Commission recommended the government to indemnify the

victims of the Mendiola incident and the acts and utterances of President

Aquino which is sympathetic to the cause is indicative of State's waiver of

immunity and therefore, the government should also be liable and should

be compensated by the government . The case has been dismissed that

State has not waived its immunity. On the other hand, the Military Officer

filed a petition for certiorari to review the orders of the Regional Trial Court,

Branch 9.

ISSUE: Whether or not the State has waived its immunity from suit and

therefore should the State be liable for the incident?

HELD: No. The recommendation made by the Mendiola Commission

regarding the indemnification of the heirs of the deceased and the victims

of the incident does not in any way mean liability automatically attaches to

the State. The purpose of which is to investigate of the disorders that took

place and the recommendation it makes cannot in any way bind the State.

The acts and utterances of President Aquino does not mean admission of

the State of its liability. Moreover, the case does not qualify as suit against

the State. While the Republic in this case is sued by name, the ultimate

liability does not pertain to the government. The military officials are held

liable for the damages for their official functions ceased the moment they

have exceeded to their authority. They were deployed to ensure that the

rally would be peaceful and orderly and should guarantee the safety of the

people. The court has made it quite clear that even a high position in the

government does not confer a license to persecute or recklessly injure

another. The court rules that there is no reversible error and no grave

abuse of discretion committed by the respondent Judge in issuing the

questioned orders.

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

G.R. No. L-26400 February 29, 1972

VICTORIA AMIGABLE, plaintiff-appellant, vs. NICOLAS CUENCA, as

Commissioner of Pub. Highways and REP. OF THE PHIL,

defendants-appellees.

This is an appeal from the decision of the Court of First Instance of Cebu

dismissing the plaintiff's complaint.

FACTS: Victoria Amigable, is the registered owner of a lot in Cebu City.

Without prior expropriation or negotiated sale, the government used a

portion of said lot for the construction of the Mango and Gorordo Avenues.

On March 27, 1958 Amigable's counsel wrote the President of the

Philippines, requesting payment of the portion of her lot which had been

appropriated by the government. The claim was indorsed to the Auditor

General, who disallowed it in his 9th Endorsement. Thus, Amigable filed in

the court a quo a complaint against the Republic of the Philippines and

Nicolas Cuenca (Commissioner of Public Highways) for the recovery of

ownership and possession of her lot. The defendants denied the plaintiffs

allegations stating: (1) that the action was premature, the claim not having

been filed first with the Office of the Auditor General; (2) that the right of

action for the recovery had already prescribed; (3) that the action being a

suit against the Government, the claim for moral damages, attorney's fees

and costs had no valid basis since the Government had not given its

consent to be sued; and(4) that inasmuch as it was the province of Cebu

that appropriated and used the area involved in the construction of Mango

Avenue, plaintiff had no cause of action against the defendants. On July 29,

1959, the court rendered its decision holding that it had no jurisdiction

over the plaintiff's cause of action for the recovery of possession and

ownership of the lot on the ground that the government cannot be sued

without its consent; that it had neither original nor appellate jurisdiction to

hear and decide plaintiff's claim for compensatory damages, being a money

claim against the government; and that it had long prescribed, nor did it

have jurisdiction over said claim because the government had not given its

consent to be sued. Accordingly, the complaint was dismissed.

ISSUE: W/N the appellant may properly sue the government

RULING: Yes. Considering that no annotation in favor of the government

appears at the back of her certificate of title and that she has not executed

any deed of conveyance of any portion of her lot to the government, the

appellant remains the owner of the whole lot. As registered owner, she

could bring an action to recover possession of the portion of land in

question at anytime because possession is one of the attributes

of ownership. However, since restoration of possession of said portion by

the government is neither convenient nor feasible at this time because it is

now and has been used for road purposes, the only relief available is for

the government to make due compensation which it could and should have

done years ago. To determine the due compensation for the land, the basis

should be the price or value thereof at the time of the taking.

As regards the claim for damages, the plaintiff is entitled thereto in the

form of legal interest on the price of the land from the time it was taken up

to the time that payment is made by the government. In addition, the

government should pay for attorney's fees, the amount of which should be

fixed by the trial court after hearing. WHEREFORE, the decision appealed

from is hereby set aside and the case remanded to the court a quo for the

determination of compensation, including attorney's fees, to which the

appellant is entitled as above indicated.

REPUBLIC VS. VILLASOR, ET AL.

G.R. No. L-30671November 28, 1973

Facts: On July 7, 1969, a decision was rendered in Special Proceedings No.

2156-R in favor of respondents P.J. Kiener Co., Ltd., Gavino Unchuan, and

International Construction Corporation and against petitioner confirming

the arbitration award in the amount of P1, 712,396.40. The award is for

the satisfaction of a judgment against the Philippine Government. On June

24, 1969, respondent Honorable Guillermo Villasor issued an

Order declaring the decision final and executory. Villasor directed the

Sheriffs of Rizal Province, Quezon City as well as Manila to execute said

decision. The Provincial Sheriff of Rizal served Notices of Garnishment with

several Banks, specially on Philippine Veterans Bank and PNB. The funds of

the Armed Forces of the Philippines on deposit with Philippine Veterans

Bank and PNB are public funds duly appropriated and allocated for the

payment of pensions of retirees, pay and allowances of military and civilian

personnel and for maintenance and operations of the AFP. Petitioner, on

certiorari, filed prohibition proceedings against respondent Judge Villasor

for acting in excess of jurisdiction with grave abuse of discretion amounting

to lack of jurisdiction in granting the issuance of a Writ of Execution against

the properties of the AFP, hence the notices and garnishment are null and

void.

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

Issue: Is the Writ of Execution issued by Judge Villasor valid?

Held: What was done by respondent Judge is not in conformity with the

dictates of the Constitution. It is a fundamental postulate of

constitutionalism flowing from the juristic concept of sovereignty that the

state as well as its government is immune from suit unless it gives its

consent. A sovereign is exempt from suit, not because of any formal

conception or obsolete theory, but on the logical and practical ground that

there can be no legal right as against the authority that makes the law on

which the right depends. The State may not be sued without its consent. A

corollary, both dictated by logic and sound sense from a basic concept is

that public funds cannot be the object of a garnishment proceeding even if

the consent to be sued had been previously granted and the state liability

adjudged. The universal rule that where the State gives its consent to be

sued by private parties either by general or special law, it may limit

claimants action only up to the completion of proceedings anterior to the

stage of execution and that the power of the Courts ends when the

judgment is rendered, since the government funds and properties may not

be seized under writs of execution or garnishment to satisfy

such judgments, is based on obvious considerations of public policy.

Disbursements of public funds must be covered by the corresponding

appropriation as required by law. The functions and public services

rendered by the State cannot be allowed to be paralyzed or disrupted by

the diversion of public funds from their legitimate and specific objects, as

appropriated by law.

Dept. of Agriculture vs. NLRC

Facts: Petitioner Department of Agriculture (DA) and Sultan Security

Agency entered into a contract for security services to be provided by the

latter to the said governmental entity. Pursuant to their arrangements,

guards were deployed by Sultan Security Agency in the various premises of

the DA. Thereafter, several guards filed a complaint for underpayment of

wages, nonpayment of 13th month pay, uniform allowances, night shift

differential pay, holiday pay, and overtime pay, as well as for damages

against

the

DA

and

the

security

agency.

The Labor Arbiter rendered a decision finding the DA jointly and severally

liable with the security agency for the payment of money claims of the

complainant security guards. The DA and the security agency did not

appeal the decision. Thus, the decision became final and executory. The

Labor Arbiter issued a writ of execution to enforce and execute the

judgment against the property of the DA and the security agency.

Thereafter, the City Sheriff levied on execution the motor vehicles of the

DA.

Issue: Whether or not the doctrine of non-suability of the State applies in

the

case

Held: The basic postulate enshrined in the Constitution that the State

may not be sued without its consent reflects nothing less than a

recognition of the sovereign character of the State and an express

affirmation of the unwritten rule effectively insulating it from the

jurisdiction of courts. It is based on the very essence of sovereignty. A

sovereign is exempt from suit based on the logical and practical ground

that there can be no legal right as against the authority that makes the law

on

which

the

right

depends.

The rule is not really absolute for it does not say that the State may not be

sued under any circumstances. The State may at times be sued. The

States consent may be given expressly or impliedly. Express consent may

be made through a general law or a special law. Implied consent, on the

other hand, is conceded when the State itself commences litigation, thus

opening itself to a counterclaim, or when it enters into a contract. In this

situation, the government is deemed to have descended to the level of the

other contracting party and to have divested itself of its sovereign

immunity.

But not all contracts entered into by the government operate as a waiver of

its non-suability; distinction must still be made between one which is

executed in the exercise of its sovereign function and another which is

done in its proprietary capacity. A State may be said to have descended to

the level of an individual and can this be deemed to have actually given its

consent to be sued only when it enters into business contracts. It does not

apply where the contract relates to the exercise of its sovereign functions.

In the case, the DA has not pretended to have assumed a capacity apart

from its being a governmental entity when it entered into the questioned

contract; nor that it could have, in fact, performed any act proprietary in

character.

But, be that as it may, the claims of the complainant security guards

clearly constitute money claims. Act No. 3083 gives the consent of the

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

State to be sued upon any moneyed claim involving liability arising from

contract, express or implied. Pursuant, however, to Commonwealth Act

327, as amended by PD 1145, the money claim must first be brought to

the Commission on Audit.

although they are considered to be public in character, they are not exempt

from garnishment (legal proceedings).

GAUDENCIO RAYO vs. COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE OF BULACAN

G.R. No. L-55273-83 December 19, 1981

RAYO vs. CFI of BULACAN

Facts:

1. During the height of typhoon Kading, the National Power Corporations

plant superintendent Chavez opened simultaneously all the three

floodgates of the Angat Dam.

2. As a direct and immediate result, several towns in Bulacan were flooded

(particularly Norzagaray). About a hundred of its residents died and

properties worth million of pesos were destroyed.

3. The petitioners, who are among the unfortunate victims of the mancaused flood, filed several complaints for damages against NPC and the

plant superintendent.

4. NPC claimed, as its defense, that in the operation of the Angat Dam, it is

performing a purely governmental function. Thus, it cannot be sued

without the express consent of the State.

5. The petitioners opposed the claim of NPC and claimed that it is

performing not governmental but merely proprietary functions and that

based on the organic charter (charter -a legal document that provides for

the creation of a corporate entity) of NPC, it can be sued and be sued in

any court.

Issue: Whether or not the power of NPC to sue and be sued under its

organic charter includes the power to be sued for tort.

FACTS: At the height of the infamous typhoon "Kading", the respondent

opened simultaneously all the three floodgates of the Angat Dam which

resulted in a sudden, precipitate and simultaneous opening of said

floodgates several towns in Bulacan were inundated. The petitioners filed

for damages against the respondent corporation.

Petitioners opposed the prayer of the respondents from dismissal of the

case and contended that the respondent corporation is merely performing a

propriety functions and that under its own organic act, it can sue and be

sued in court.

ISSUE:

1.

2.

W/N the respondent performs governmental functions with

respect to the management and operation of the Angat Dam.

W/N the power of the respondent to sue and be sued under its

organic charter includes the power to be sued for tort.

HELD: The government has organized a private corporation, put money in

it and has allowed it to sue and be sued in any court under its charter.

As a government owned and controlled corporation, it has a personality of

its own, distinct and separate from that of the government. Moreover, the

charter provision that it can sue and be sued in any court.

BUREAU

OF

PRINTING,

SERAFIN

SALVADOR

and

MARIANO

Held: The government has organized a private corporation, put money in it

and has allowed it to sue and be sued in any court under its charter. NPC,

as a government owned and controlled corporation, has a personality of its

own, distinct and separate from that of the Government. In any court, NPC

can sue and be sued for tort. The petition of the petitioners was granted.

LEDESMA, petitioners, vs. THE BUREAU OF PRINTING EMPLOYEES

Notes: Government-owned and controlled corporations have a personality

of their own, separate and distinct from the government. Therefore,

Facts: The action in question was upon complaint of the respondents

ASSOCIATION (NLU), et al. respondents.

G.R. No. L-15751 January 28, 1961

Bureau of Printing Employees Association (NLU) Pacifico Advincula, Roberto

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

Mendoza, Ponciano Arganda and Teodulo Toleran filed by an acting

Note: The Bureau of Printing is an office of the Government created by the

prosecutor of the Industrial Court against herein petitioner Bureau of

Administrative Code of 1916 (Act No. 2657). As such instrumentality of the

Printing, Serafin Salvador, the Acting Secretary of the Department

Government, it operates under the direct supervision of the Executive

of General Services, and Mariano Ledesma the Director of the Bureau of

Secretary, Office of the President, and is "charged with the execution of all

Printing. The complaint alleged that Serafin Salvador and Mariano Ledesma

printing and binding, including work incidental to those processes, required

have been engaging in unfair labor practices by interfering with, or

by the National Government and such other work of the same character as

coercing the employees of the Bureau of Printing particularly the members

said Bureau may, by law or by order of the (Secretary of Finance)Executive

of the complaining association petition, in the exercise of their right to self-

Secretary, be authorized to undertake . . .." (See. 1644, Rev. Adm. Code).

organization an discriminating in regard to hire and tenure of their

It has no corporate existence, and its appropriations are provided for in the

employment in order to discourage them from pursuing the union

General Appropriations Act. Designed to meet the printing needs of the

activities.The petitioners Bureau of Printing, Serafin Salvador and Mariano

Government, it is primarily a service bureau and obviously, not engaged in

Ledesma denied the charges of unfair labor practices attributed to the and,

business or occupation for pecuniary profit.

by way of affirmative defenses, alleged, among other things, that

respondents Pacifico Advincula, Roberto Mendoza Ponciano Arganda and

Teodulo Toleran were suspended pending result of an administrative

investigation against them for breach of Civil Service rules and regulations

petitions; that the Bureau of Printing has no juridical personality to sue and

be sued; that said Bureau of Printing is not an industrial concern engaged

for the purpose of gain but is an agency of the Republic performing

government functions. For relief, they prayed that the case be dismissed

for lack of jurisdiction. Thereafter, before the case could be heard,

petitioners filed an "Omnibus Motion" asking for a preliminary hearing on

the question of jurisdiction raised by them in their answer and for

suspension of the trial of the case on the merits pending the determination

of such jurisdictional question. The motion was granted, but after hearing,

the trial judge of the Industrial Court in an order dated January 27, 1959

sustained the jurisdiction of the court on the theory that the functions of

the Bureau of Printing are "exclusively proprietary in nature," and,

consequently, denied the prayer for dismissal. Reconsideration of this order

was also denied by the court en banc.

Issue: whether or not Bureau of Printing can be sued.

Ruling: No. Indeed, as an office of the Government, without any corporate

or juridical personality, the Bureau of Printing cannot be sued. Any suit,

action or proceeding against it, if it were to produce any effect, would

actually be a suit, action or proceeding against the Government itself, and

the rule is settled that the Government cannot be sued without its consent,

much less over its objection. t is true that the Bureau of Printing receives

outside jobs and that many of its employees are paid for overtime work on

regular working days and on holidays, but these facts do not justify the

conclusion that its functions are "exclusively proprietary in nature."

Overtime work in the Bureau of Printing is done only when the interest of

the service so requires. As a matter of administrative policy, the overtime

compensation may be paid, but such payment is discretionary with the

head of the Bureau depending upon its current appropriations, so that it

cannot be the basis for holding that the functions of said Bureau are wholly

proprietary in character. Clearly, while the Bureau of Printing is allowed to

undertake private printing jobs, it cannot be pretended that it is thereby an

industrial or business concern. The additional work it executes for private

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

parties is merely incidental to its function, and although such work may be

Bureau of Printing is an office of the Government created by the

deemed proprietary in character, there is no showing that the employees

Administrative Code of 1916 (Act No. 2657). As such instrumentality of the

performing said proprietary function are separate and distinct from those

Government, it operates under the direct supervision of the Executive

employed in its general governmental functions.

Secretary, Office of the President, and is "charged with the execution of all

printing and binding, including work incidental to those processes, required

Bureau of Printing vs Bureau of Printing Employees Association

by the National Government and such other work of the same character as

G.R. No. L-15751 January 28, 1961 1 SCRA 340

said Bureau may, by law or by order of the Executive Secretary, be

Facts: Upon complaint of the respondents of the Bureau of Printing

Employees Association against the Bureau of Printing, the complaint

alleged that the latter have been engaging in unfair labor practices by

interfering with, or coercing their employees, in the exercise of their right

to self-organization and discriminating in regard to hire and tenure of their

employment in order to discourage them from pursuing the union

activities. The Petitioners of Bureau of Printing denied the charges of unfair

labor practices attributed to and, by way of affirmative defenses, alleged,

among other things, that the respondents of the Bureau of Printing

Employees

Association

were

suspending

the

pending

result

of

an

administrative investigation against them for breach of Civil Service rules

and regulations petition; that the Bureau of Printing has no juridical

personality to sue and be sued; that said bureau is not an industrial

concern engaged for the purpose of gain but is an agency of the Republic

performing government functions. The petitioners filed an "Omnibus

Motion" asking for a preliminary hearing on the question of jurisdiction

raised by them in their answer and for suspension of the trial of the case

on the merits pending the determination of such juridical question.

Issue: Whether or not the Bureau of Printing, in the proceeding in the

action for unfair labor practice, lacks jurisdiction thereof.

authorized to undertake...". It has no corporate existence, and its

appropriations are provided for in the General Appropriations Act. Designed

to meet the printing needs of the Government, it is primarily a service

bureau

and obviously, not engaged in

business or occupation for

pecuniary profit. Overtime work in the Bureau of Printing is done only when

the interest of the service so requires. As a matter of administrative policy,

the overtime compensation may be paid, but such payment is discretionary

with the head of the Bureau depending upon its current appropriations, so

that it cannot be the basis for holding that the functions of said Bureau are

wholly proprietary in character. The additional work it executes for private

parties is merely incidental to its function, and although such work may be

deemed proprietary in character, there is no showing that the employees

performing said proprietary function are separate and distinct from those

employed in its general governmental functions. As an office of the

Government, without any corporate or juridical personality, the Bureau of

Printing cannot be sued. Any suit, action or proceeding against it, if it were

to produce any effect, would actually be a suit, action or proceeding

against the Government itself, and the rule is settled that the Government

cannot be sued without its consent, much less over its objection.

Civil Aeronautics Administration v. Court of Appeals - Not all

government entities whether corporate or not are immune from suits.

Held: The trial judge of the Industrial Court in an order dated January 27,

Immunity from suits is determined by the character of the objects for

1959 sustained the jurisdiction of the court on the theory that the functions

which the entity was organized. - Suits against State agencies with relation

of the Bureau of Printing are "exclusively proprietary in nature,". The

to matters in which they have assumed to act in private or non-

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

governmental capacity, and various suits against certain corporations

created by the State to engage In matters partaking more of the nature of

ordinary business are not regarded as suits against the State

G.R. No. L-51806 November 8, 1988

CIVIL

AERONAUTICS

ADMINISTRATION,

petitioner,

vs. COURT OF APPEALS and ERNEST E. SIMKE, respondents. The

Solicitor General for petitioner. Ledesma, Guytingco, Veleasco &

Associates for respondent Ernest E. Simke.

Private respondent then filed an action for damages based on quasi-delict

with the Court of First Instance of Rizal, Branch VII against petitioner Civil

Aeronautics Administration or CAA as the entity empowered "to administer,

operate, manage, control, maintain and develop the Manila International

Airport ... ." [Sec. 32 (24), R.A. 776].

Said claim for damages included, aside from the medical and hospital bills,

consequential damages for the expenses of two lawyers who had to go

abroad in private respondent's stead to finalize certain business

transactions and for the publication of notices announcing the

postponement of private respondent's daughter's wedding which had to be

cancelled because of his accident [Record on Appeal, p. 5].

CORTES, J.:

Assailed in this petition for review on certiorari is the decision of the Court

of Appeals affirming the trial court decision which reads as follows:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered ordering defendant to pay

plaintiff the amount of P15,589.55 as full reimbursement of his actual

medical and hospital expenses, with interest at the legal rate from the

commencement of the suit; the amount of P20,200.00 as consequential

damages; the amount of P30,000.00 as moral damages; the amount of

P40,000.00 as exemplary damages; the further amount of P20,000.00 as

attorney's fees and the costs [Rollo, p. 24].

Judgment was rendered in private respondent's favor prompting petitioner

to appeal to the Court of Appeals. The latter affirmed the trial court's

decision. Petitioner then filed with the same court a Motion for,

Reconsideration but this was denied.

Petitioner now comes before this Court raising the following assignment of

errors:

1. The Court of Appeals gravely erred in not holding that the present the

CAA is really a suit against the Republic of the Philippines which cannot be

sued without its consent, which was not given in this case.

In the afternoon of December 13, 1968, private respondent with several

other persons went to the Manila International Airport to meet his future

son-in-law. In order to get a better view of the incoming passengers, he

and his group proceeded to the viewing deck or terrace of the airport.

2. The Court of Appeals gravely erred in finding that the injuries of

respondent Ernest E. Simke were due to petitioner's negligence although

there was no substantial evidence to support such finding; and that the

inference that the hump or elevation the surface of the floor area of the

terrace of the fold) MIA building is dangerous just because said respondent

tripped over it is manifestly mistaken circumstances that justify a review

by this Honorable Court of the said finding of fact of respondent appellate

court (Garcia v. Court of Appeals, 33 SCRA 622; Ramos v. CA, 63 SCRA

331.)

While walking on the terrace, then filled with other people, private

respondent slipped over an elevation about four (4) inches high at the far

end of the terrace. As a result, private respondent fell on his back and

broke his thigh bone.

3. The Court of Appeals gravely erred in ordering petitioner to pay actual,

consequential, moral and exemplary damages, as well as attorney's fees to

respondent Simke although there was no substantial and competent

proof to support said awards I Rollo, pp. 93-94 1.

The facts of the case are as follows:

Private respondent is a naturalized Filipino citizen and at the time of the

incident was the Honorary Consul Geileral of Israel in the Philippines.

The next day, December 14, 1968, private respondent was operated on for

about three hours.

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

I. Invoking the rule that the State cannot be sued without its consent,

petitioner contends that being an agency of the government, it cannot be

made a party-defendant in this case.

This Court has already held otherwise in the case of National Airports

Corporation v. Teodoro, Sr. [91 Phil. 203 (1952)]. Petitioner contends that

the said ruling does not apply in this case because: First, in the Teodoro

case, the CAA was sued only in a substituted capacity, the National Airports

Corporation being the original party. Second, in the Teodoro case, the

cause of action was contractual in nature while here, the cause of action is

based on a quasi-delict. Third, there is no specific provision in Republic Act

No. 776, the law governing the CAA, which would justify the conclusion

that petitioner was organized for business and not for governmental

purposes. [Rollo, pp. 94-97].

Second, the Teodoro case did not make any qualification or limitation as to

whether or not the CAA's power to sue and be sued applies only to

contractual obligations. The Court in the Teodoro case ruled that Sections 3

and 4 of Executive Order 365 confer upon the CAA, without any

qualification, the power to sue and be sued, albeit only by implication.

Accordingly, this Court's pronouncement that where such power to sue and

be sued has been granted without any qualification, it can include a claim

based on tort or quasi-delict [Rayo v. Court of First Instance of Bulacan,

G.R. Nos. 55273-83, December 19,1981, 1 1 0 SCRA 4561 finds relevance

and applicability to the present case.

Third, it has already been settled in the Teodoro case that the CAA as an

agency is not immune from suit, it being engaged in functions pertaining to

a private entity.

Such arguments are untenable.

xxx xxx xxx

First, the Teodoro case, far from stressing the point that the CAA was only

substituted for the National Airports Corporation, in fact treated the CAA as

the real party in interest when it stated that:

The Civil Aeronautics Administration comes under the category of a private

entity. Although not a body corporate it was created, like the National

Airports Corporation, not to maintain a necessary function of government,

but to run what is essentially a business, even if revenues be not its prime

objective but rather the promotion of travel and the convenience of the

travelling public. It is engaged in an enterprise which, far from being the

exclusive prerogative of state, may, more than the construction of public

roads, be undertaken by private concerns. [National Airports Corp. v.

Teodoro, supra, p. 207.]

xxx xxx xxx

... To all legal intents and practical purposes, the National Airports

Corporation is dead and the Civil Aeronautics Administration is its heir or

legal representative, acting by the law of its creation upon its own rights

and in its own name. The better practice there should have been to make

the Civil Aeronautics Administration the third party defendant instead of

the National Airports Corporation. [National Airports Corp. v. Teodoro,

supra, p. 208.]

xxx xxx xxx

xxx xxx xxx

True, the law prevailing in 1952 when the Teodoro case was promulgated

was Exec. Order 365 (Reorganizing the Civil Aeronautics Administration

and Abolishing the National Airports Corporation). Republic Act No. 776

(Civil Aeronautics Act of the Philippines), subsequently enacted on June 20,

1952, did not alter the character of the CAA's objectives under Exec, Order

365. The pertinent provisions cited in the Teodoro case, particularly Secs. 3

and 4 of Exec. Order 365, which led the Court to consider the CAA in the

category of a private entity were retained substantially in Republic Act 776,

Sec. 32 (24) and (25).<re||an1w> Said Act provides:

Sec. 32. Powers and Duties of the Administrator. Subject to the general

control and supervision of the Department Head, the Administrator shall

have among others, the following powers and duties:

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

xxx xxx xxx

(24) To administer, operate, manage, control, maintain and develop the

Manila International Airport and all government-owned aerodromes except

those controlled or operated by the Armed Forces of the Philippines

including such powers and duties as: (a) to plan, design, construct, equip,

expand, improve, repair or alter aerodromes or such structures,

improvement or air navigation facilities; (b) to enter into, make and

execute contracts of any kind with any person, firm, or public or private

corporation or entity; ... .

(25) To determine, fix, impose, collect and receive landing fees, parking

space fees, royalties on sales or deliveries, direct or indirect, to any aircraft

for its use of aviation gasoline, oil and lubricants, spare parts, accessories

and supplies, tools, other royalties, fees or rentals for the use of any of the

property under its management and control.

xxx xxx xxx

From the foregoing, it can be seen that the CAA is tasked with private or

non-governmental functions which operate to remove it from the purview

of the rule on State immunity from suit. For the correct rule as set forth in

the Tedoro case states:

xxx xxx xxx

Not all government entities, whether corporate or non-corporate, are

immune from suits. Immunity functions suits is determined by the

character of the objects for which the entity was organized. The rule is thus

stated in Corpus Juris:

Suits against State agencies with relation to matters in which they have

assumed to act in private or non-governmental capacity, and various suits

against certain corporations created by the state for public purposes, but to

engage in matters partaking more of the nature of ordinary business rather

than functions of a governmental or political character, are not regarded as

suits against the state. The latter is true, although the state may own stock

or property of such a corporation for by engaging in business operations

through a corporation, the state divests itself so far of its sovereign

character, and by implication consents to suits against the corporation. (59

C.J., 313) [National Airport Corporation v. Teodoro, supra, pp. 206-207;

Emphasis supplied.]

This doctrine has been reaffirmed in the recent case of Malong v. Philippine

National Railways [G.R. No. L-49930, August 7, 1985, 138 SCRA 631,

where it was held that the Philippine National Railways, although owned

and operated by the government, was not immune from suit as it does not

exercise sovereign but purely proprietary and business functions.

Accordingly, as the CAA was created to undertake the management of

airport operations which primarily involve proprietary functions, it cannot

avail of the immunity from suit accorded to government agencies

performing strictly governmental functions.

II. Petitioner tries to escape liability on the ground that there was no basis

for a finding of negligence. There can be no negligence on its part, it

alleged, because the elevation in question "had a legitimate purpose for

being on the terrace and was never intended to trip down people and injure

them. It was there for no other purpose but to drain water on the floor

area of the terrace" [Rollo, P. 99].

To determine whether or not the construction of the elevation was done in

a negligent manner, the trial court conducted an ocular inspection of the

premises.

xxx xxx xxx

... This Court after its ocular inspection found the elevation shown in Exhs.

A or 6-A where plaintiff slipped to be a step, a dangerous sliding step, and

the proximate cause of plaintiffs injury...

xxx xxx xxx

This Court during its ocular inspection also observed the dangerous and

defective condition of the open terrace which has remained unrepaired

through the years. It has observed the lack of maintenance and upkeep of

the MIA terrace, typical of many government buildings and offices. Aside

from the litter allowed to accumulate in the terrace, pot holes cause by

missing tiles remained unrepaired and unattented. The several elevations

shown in the exhibits presented were verified by this Court during the

ocular inspection it undertook. Among these elevations is the one (Exh. A)

where plaintiff slipped. This Court also observed the other hazard, the

slanting or sliding step (Exh. B) as one passes the entrance door leading to

the terrace [Record on Appeal, U.S., pp. 56 and 59; Emphasis supplied.]

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

The Court of Appeals further noted that:

The inclination itself is an architectural anomaly for as stated by the said

witness, it is neither a ramp because a ramp is an inclined surface in such a

way that it will prevent people or pedestrians from sliding. But if, it is a

step then it will not serve its purpose, for pedestrian purposes. (tsn, p. 35,

Id.) [rollo, p. 29.]

These factual findings are binding and conclusive upon this Court. Hence,

the CAA cannot disclaim its liability for the negligent construction of the

elevation since under Republic Act No. 776, it was charged with the duty of

planning, designing, constructing, equipping, expanding, improving,

repairing or altering aerodromes or such structures, improvements or air

navigation facilities [Section 32, supra, R.A. 776]. In the discharge of this

obligation, the CAA is duty-bound to exercise due diligence in overseeing

the construction and maintenance of the viewing deck or terrace of the

airport.

It must be borne in mind that pursuant to Article 1173 of the Civil Code,

"(t)he fault or negligence of the obligor consists in the omission of that

diligence which is required by the nature of the obligation and corresponds

with the circumstances of the person, of the time and of the place." Here,

the obligation of the CAA in maintaining the viewing deck, a facility open to

the public, requires that CAA insure the safety of the viewers using it. As

these people come to the viewing deck to watch the planes and

passengers, their tendency would be to look to where the planes and the

incoming passengers are and not to look down on the floor or pavement of

the viewing deck. The CAA should have thus made sure that no dangerous

obstructions or elevations exist on the floor of the deck to prevent any

undue harm to the public.

The legal foundation of CAA's liability for quasi-delict can be found in Article

2176 of the Civil Code which provides that "(w)hoever by act or omission

causes damage to another, there being fault or negligence, is obliged to

pay for the damage done... As the CAA knew of the existence of the

dangerous elevation which it claims though, was made precisely in

accordance with the plans and specifications of the building for proper

drainage of the open terrace [See Record on Appeal, pp. 13 and 57; Rollo,

p. 391, its failure to have it repaired or altered in order to eliminate the

existing hazard constitutes such negligence as to warrant a finding of

liability based on quasi-delict upon CAA.

The Court finds the contention that private respondent was, at the very

least, guilty of contributory negligence, thus reducing the damages that

plaintiff may recover, unmeritorious. Contributory negligence under Article

2179 of the Civil Code contemplates a negligent act or omission on the part

of the plaintiff, which although not the proximate cause of his injury,

contributed to his own damage, the proximate cause of the plaintiffs own

injury being the defendant's lack of due care. In the instant case, no

contributory negligence can be imputed to the private respondent,

considering the following test formulated in the early case of Picart v.

Smith, 37 Phil. 809 (1918):

The test by which to determine the existence of negligence in a particular

case may be stated as follows: Did the defendant in doing the alleged

negligent act use that reasonable care and caution which an ordinarily

prudent man would have used in the same situation? If not, then he is

guilty of negligence. The law here in effect adopts the standard supposed

to be supplied by the imaginary conduct of the discreet paterfamilias of the

Roman law. The existence of the negligence in a given case is not

determined by reference to the personal judgment of the actor in the

situation before him. The law considers what would be reckless,

blameworthy, or negligent in the man of ordinary intelligence and prudence

and determines liability by that.

The question as to what would constitute the conduct of a prudent man in

a given situation must of course be always determined in the light of

human experience and in view of the facts involved in the particular case.

Abstract speculations cannot be here of much value but this much can be

profitably said: Reasonable men-overn their conduct by the circumstances

which are before them or known to them. They are not, and are not

supposed to be omniscient of the future. Hence they can be expected to

take care only when there is something before them to suggest or warn of

danger. Could a prudent man, in the case under consideration, foresee

harm as a result of the course actually pursued' If so, it was the duty of the

actor to take precautions to guard against that harm. Reasonable foresight

of harm, followed by the ignoring of the suggestion born of this prevision,

is always necessary before negligence can be held to exist.... [Picart v.

Smith, supra, p. 813; Emphasis supplied.]

The private respondent, who was the plaintiff in the case before the lower

court, could not have reasonably foreseen the harm that would befall him,

considering the attendant factual circumstances. Even if the private

respondent had been looking where he was going, the step in question

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

could not easily be noticed because of its construction. As the trial court

found:

In connection with the incident testified to, a sketch, Exhibit O, shows a

section of the floorings oil which plaintiff had tripped, This sketch reveals

two pavements adjoining each other, one being elevated by four and onefourth inches than the other. From the architectural standpoint the higher,

pavement is a step. However, unlike a step commonly seen around, the

edge of the elevated pavement slanted outward as one walks to one

interior of the terrace. The length of the inclination between the edges of

the two pavements is three inches. Obviously, plaintiff had stepped on the

inclination because had his foot landed on the lower pavement he would

not have lost his balance. The same sketch shows that both pavements

including the inclined portion are tiled in red cement, and as shown by the

photograph Exhibit A, the lines of the tilings are continuous. It would

therefore be difficult for a pedestrian to see the inclination especially where

there are plenty of persons in the terrace as was the situation when

plaintiff fell down. There was no warning sign to direct one's attention to

the change in the elevation of the floorings. [Rollo, pp. 2829.]

III. Finally, petitioner appeals to this Court the award of damages to private

respondent. The liability of CAA to answer for damages, whether actual,

moral or exemplary, cannot be seriously doubted in view of one conferment

of the power to sue and be sued upon it, which, as held in the case of Rayo

v. Court of First Instance, supra, includes liability on a claim for quasi-dilict.

In the aforestated case, the liability of the National Power Corporation to

answer for damages resulting from its act of sudden, precipitate and

simultaneous opening of the Angat Dam, which caused the death of several

residents of the area and the destruction of properties, was upheld since

the o,rant of the power to sue and be sued upon it necessarily implies that

it can be held answerable for its tortious acts or any wrongful act for that

matter.

With respect to actual or compensatory damages, the law mandates that

the same be proven.

Art. 2199. Except as provided by law or by stipulation, one are entitled to

an adequate compensation only for such pecuniary loss suffered by him as

he has duly proved. Such compensation is referred to as actual on

compensatory damages [New Civil Code].

Private respondent claims P15,589.55 representing medical and

hospitalization bills. This Court finds the same to have been duly proven

through the testimony of Dr. Ambrosio Tangco, the physician who attended

to private respondent (Rollo, p. 26) and who Identified Exh. "H" which was

his bill for professional services [Rollo, p. 31].

Concerning the P20,200.00 alleged to have been spent for other expenses

such as the transportation of the two lawyers who had to represent private

respondent abroad and the publication of the postponement notices of the

wedding, the Court holds that the same had also been duly proven. Private

respondent had adequately shown the existence of such losses and the

amount thereof in the testimonies before the trial court [CA decision, p. 81.

At any rate, the findings of the Court of Appeals with respect to this are

findings of facts [One Heart Sporting Club, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, G.R.

Nos. 5379053972, Oct. 23, 1981, 108 SCRA 4161 which, as had been held

time and again, are, as a general rule, conclusive before this Court [Sese v.

Intermediate Appellate Court, G.R. No. 66186, July 31, 1987,152 SCRA

585].

With respect to the P30,000.00 awarded as moral damages, the Court

holds private respondent entitled thereto because of the physical suffering

and physical injuries caused by the negligence of the CAA [Arts. 2217 and

2219 (2), New Civil Code].

With respect to the award of exemplary damages, the Civil Code explicitly,

states:

Art. 2229. Exemplary or corrective damages, are imposed, by way of

example or correction for the public good, in addition to the moral,

liquidated or compensatory

Art. 2231. In quasi-delicts, exemplary damages may be granted if the

defendant acted with gross negligence.

Gross negligence which, according to the Court, is equivalent to the term

"notorious negligence" and consists in the failure to exercise even slight

care [Caunan v. Compania General de Tabacos, 56 Phil. 542 (1932)] can be

attributed to the CAA for its failure to remedy the dangerous condition of

the questioned elevation or to even post a warning sign directing the

attention of the viewers to the change in the elevation of the floorings

notwithstanding its knowledge of the hazard posed by such elevation

[Rollo, pp. 28-29; Record oil Appeal, p. 57]. The wanton disregard by the

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

CAA of the safety of the people using the viewing deck, who are charged

an admission fee, including the petitioner who paid the entrance fees to get

inside the vantage place [CA decision, p. 2; Rollo, p. 25] and are,

therefore, entitled to expect a facility that is properly and safely maintained

justifies the award of exemplary damages against the CAA, as a

deterrent and by way of example or correction for the public good. The

award of P40,000.00 by the trial court as exemplary damages

appropriately underscores the point that as an entity changed with

providing service to the public, the CAA. like all other entities serving the

public. has the obligation to provide the public with reasonably safe

service.

Finally, the award of attorney's fees is also upheld considering that under

Art. 2208 (1) of the Civil Code, the same may be awarded whenever

exemplary damages are awarded, as in this case, and,at any rate, under

Art. 2208 (11), the Court has the discretion to grant the same when it is

just and equitable.

However, since the Manila International Airport Authority (MIAA) has taken

over the management and operations of the Manila International Airport

[renamed Ninoy Aquino International Airport under Republic Act No. 6639]

pursuant to Executive Order No. 778 as amended by executive Orders Nos.

903 (1983), 909 (1983) and 298 (1987) and under Section 24 of the said

Exec. Order 778, the MIAA has assumed all the debts, liabilities and

obligations of the now defunct Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA), the

liabilities of the CAA have now been transferred to the MIAA.

WHEREFORE, finding no reversible error, the Petition for review on

certiorari is DENIED and the decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. No.

51172-R is AFFIRMED. SO ORDERED.

MUNICIPALITY OF SAN FERNANDO, LA UNION vs. FIRMEG.R. No. L52179 April 8, 1991

Facts:

A collision occurred involving a passenger jeepney owned by the Estate

of Macario Nieveras, a gravel and sand truck owned by Tanquilino

Velasquez and a dumptruck of the Municipality of San Fernando, La Union

and driven by Alfredo Bislig. Due to the impact, several passengers of the

jeepney including Laureano Bania Sr. died as a result of the injuries they

sustained and four (4) others suffered varying degrees of physical injuries.

On December 11, 1966, the private respondents instituted a compliant for

damages against the Estate of Macario Nieveras and Bernardo Balagot,

owner and driver, respectively, of the passenger jeepney. However, the

aforesaid defendants filed a Third Party Complaint against the petitioner

and the driver of a dump truck of petitioner. Petitioner filed its answer and

raised affirmative defenses such as lack of cause of action, non-suability of

the State, prescription of cause of action and the negligence of the owner

and driver of the passenger jeepney as the proximate cause of the

collision. Respondent Judge Romeo N. Firme ordered defendants

Municipality of San Fernando, La Union and Alfredo Bislig to pay, jointly and

severally, the plaintiffs for funeral expenses. Private respondents stress

that petitioner has not considered that every court, including respondent

court, has the inherent power to amend and control its process and orders

so as to make them conformable to law and justice.

Issue: Whether or not the respondent court committed grave abuse of

discretion whenit deferred and failed to resolve the defense of non-suability

of the State amounting tolack of jurisdiction in a motion to dismiss.

Ruling: Non-suability of the state. The doctrine of non-suability of the

State is expressly provided for in Article XVI, Section 3 of the Constitution,

to wit: "the State may not be sued without its consent."Consent takes the

form of express or implied consent. Municipal corporations, for example,

like provinces and cities, are agencies of the State when they are engaged

in governmental functions and therefore should enjoy the sovereign

immunity from suit. Nevertheless, they are subject to suit even in the

performance of such functions because their charter provided that they can

sue and be sued."Suability depends on the consent of the state to be sued,

liability on the applicable law and the established facts. The circumstance

that a state is suable does not necessarily mean that it is liable; on the

other hand, it can never be held liable if it does not first consent to be

sued. Liability is not conceded by the mere fact that the state has allowed

itself to be sued. When the state does waive its sovereign immunity, it is

only giving the plaintiff the chance to prove, if it can, that the defendant is

liable."Anent the issue of whether or not the municipality is liable for the

torts committed by its employee, the test of liability of the municipality

depends on whether or not the driver, acting in behalf of the municipality,

is performing governmental or proprietary functions.

Dual capacity of LGU. Municipal corporations exist in a dual capacity, and

their functions are twofold. In one they exercise the right springing from

sovereignty, and while in the performance of the duties pertaining thereto,

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

their acts are political and governmental. Their officers and agents in such

capacity, though elected or appointed by them, are nevertheless public

functionaries performing a public service, and as such they are officers,

agents, and servants of the state. In the other capacity the municipalities

exercise a private, proprietary or corporate right, arising from their

existence as legal persons and not as public agencies. Their officers and

agents in the performance of such functions act in behalf of the

municipalities in their corporate or individual capacity, and not for the state

or sovereign power."It has already been remarked that municipal

corporations are suable because their charters grant them the competence

to sue and be sued. Nevertheless, they are generally not liable for torts

committed by them in the discharge of governmental functions and can be

held answerable only if it can be shown that they were acting in a

proprietary capacity. In the case at bar, the driver of the dump truck of the

municipality insists that "he was on his way to the Naguilian river to get a

load of sand and gravel for the repair of San Fernando's municipal

streets."In the absence of any evidence to the contrary, the regularity of

the performance of official duty is presumed pursuant to Section 3(m) of

Rule 131 of the Revised Rules of Court. Hence, We rule that the driver of

the dump truck was performing duties or tasks pertaining to his office. We

already stressed in the case of Palafox, et. al. vs. Province of Ilocos Norte

, the District Engineer, and the Provincial Treasurer (102 Phil 1186) that

"the construction or maintenance of roads in which the truck and the driver

worked at the time of the accident are admittedly governmental

activities."After a careful examination of existing laws and jurisprudence,

We arrive at the conclusion that the municipality cannot be held liable for

the torts committed by its regular employee, who was then engaged in the

discharge of governmental functions.

Principle/s:

1. General Rule: Public funds are not subject to levy and

execution. Unless otherwise, provided by the statute.

2. States inherent power of eminent domain (expropriation)

Municipality of Makati vs. Court of Appeals

G.R. Nos. 89898-99 October 1, 1990

Facts: Petitioner Municipality of Makati expropriated a portion of land

owned by private respondents, Admiral Finance Creditors Consortium, Inc.

After proceedings, the RTC of Makati determined the cost of the said land

which the petitioner must pay to the private respondents amounting to P5,

291,666.00 minus the advanced payment of P338,160.00. It issued the

corresponding writ of execution accompanied with a writ of garnishment of

funds of the petitioner which was deposited in PNB. However, such order

was opposed by petitioner through a motion for reconsideration,

contending that its funds at the PNB could neither be garnished nor levied

upon execution, for to do so would result in the disbursement of public

funds without the proper appropriation required under the law, citing the

case of Republic of the Philippines v. Palacio. The RTC dismissed such

motion, which was appealed to the Court of Appeals; the latter affirmed

said dismissal and petitioner now filed this petition for review.

Issue: Whether or not funds of the Municipality of Makati are exempt from

garnishment and levy upon execution.

Held: It is petitioner's main contention that the orders of respondent RTC

judge involved the net amount of P4,965,506.45, wherein the funds

garnished by respondent sheriff are in excess of P99,743.94, which are

public fund and thereby are exempted from execution without the proper

appropriation required under the law. There is merit in this contention. In

this jurisdiction, well-settled is the rule that public funds are not subject to

levy and execution, unless otherwise provided for by statute. Municipal

revenues derived from taxes, licenses and market fees, and which are

intended primarily and exclusively for the purpose of financing the

governmental activities and functions of the municipality, are exempt from

execution. Absent a showing that the municipal council of Makati has

passed an ordinance appropriating the said amount from its public funds

deposited in their PNB account, no levy under execution may be validly

affected. However, this court orders petitioner to pay for the said land

which has been in their use already. This Court will not condone petitioner's

blatant refusal to settle its legal obligation arising from expropriation of

land they are already enjoying. The State's power of eminent domain

should be exercised within the bounds of fair play and justice.

Municipality of Makati vs. CA

Facts: Petitioner Municipality of Makati expropriated a portion of land

owned by private respondent Admiral Finance Creditors Consortium, Inc.

After hearing, the RTC fixed the appraised value of the property at

P5,291,666.00, and ordered petitioner to pay this amount minus the

advanced payment of P338,160.00 which was earlier released to private

respondent. It then issued the corresponding writ of execution

accompanied with a writ of garnishment of funds of the petitioner which

was deposited in PNB. Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration,

contending that its funds at the PNB could neither be garnished nor levied

upon execution, for to do so would result in the disbursement of public

funds without the proper appropriation required under the law. The RTC

denied the motion. CA affirmed; hence, petitioner filed a petition for review

before the SC.

Constitutional Law 1: State Immunity

Issue:

1. Are the funds of the Municipality of Makati exempt from garnishment

and

levy

upon

execution?

2. If so, what then is the remedy of the private respondents?

Held:

1. Yes. In this jurisdiction, well-settled is the rule that public funds are not

subject to levy and execution, unless otherwise provided for by statute.

More particularly, the properties of a municipality, whether real or personal,

which are necessary for public use cannot be attached and sold at

execution sale to satisfy a money judgment against the municipality.

Municipal revenues derived from taxes, licenses and market fees, and

which are intended primarily and exclusively for the purpose of financing

the governmental activities and functions of the municipality, are exempt

from execution. Absent a showing that the municipal council of Makati has

passed an ordinance appropriating from its public funds an amount

corresponding to the balance due under the RTC decision, no levy under

execution may be validly effected on the public funds of petitioner.

2. Nevertheless, this is not to say that private respondent and PSB are left

with no legal recourse. Where a municipality fails or refuses, without

justifiable reason, to effect payment of a final money judgment rendered

against it, the claimant may avail of the remedy of mandamus in order to

compel the enactment and approval of the necessary appropriation

ordinance, and the corresponding disbursement of municipal funds

therefore.

For three years now, petitioner has enjoyed possession and use of the

subject property notwithstanding its inexcusable failure to comply with its

legal obligation to pay just compensation. Petitioner has benefited from its

possession of the property since the same has been the site of Makati West

High School since the school year 1986-1987. This Court will not condone

petitioner's blatant refusal to settle its legal obligation arising from

expropriation proceedings it had in fact initiated. The State's power of

eminent domain should be exercised within the bounds of fair play and

justice. (Municipality of Makati vs. CA, G.R. Nos. 89898-99, October 1,

1990)

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Temporary Restraining OrderDocument5 pagesTemporary Restraining OrderBoulder City ReviewNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Dissenting Opinion of CJ Sereno in League of Cities v. COMELECDocument12 pagesDissenting Opinion of CJ Sereno in League of Cities v. COMELECJay-ar Rivera BadulisNo ratings yet

- Sales Case Digests (Atty. Casino)Document66 pagesSales Case Digests (Atty. Casino)Jamaica Cabildo Manaligod100% (3)

- Contract of Sale (Notes)Document14 pagesContract of Sale (Notes)Dael GerongNo ratings yet

- The in Pari Delicto RuleDocument1 pageThe in Pari Delicto RuleLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Filcar vs. EspinasDocument2 pagesFilcar vs. Espinasmoinky100% (1)

- Williams v Carwardine Case SummaryDocument8 pagesWilliams v Carwardine Case SummaryBhumika M ShahNo ratings yet

- Cagayan Valley vs. CADocument1 pageCagayan Valley vs. CALady BancudNo ratings yet

- BTX Notes in Constitutional Law 1 MidtermsDocument29 pagesBTX Notes in Constitutional Law 1 MidtermsChristianneNoelleDeVera100% (2)

- Services Agreement Between Client and ContractorDocument6 pagesServices Agreement Between Client and ContractorGulshad Ahmed100% (1)

- Legal Requirements of Contract ModificationDocument3 pagesLegal Requirements of Contract ModificationLady BancudNo ratings yet

- 224 SCRA 437 - Intellectual Property Law - Law On TrademarksDocument8 pages224 SCRA 437 - Intellectual Property Law - Law On TrademarksLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Spouses Del Ocampo Vs AbesiaDocument2 pagesSpouses Del Ocampo Vs AbesiamarvinNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument17 pagesCase Digestgiovanni0% (1)

- Manlar vs. DeytoDocument2 pagesManlar vs. DeytoLady BancudNo ratings yet

- CitizenshipDocument37 pagesCitizenshipLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Disposition of Obligations Under Extraordinary InflationDocument2 pagesDisposition of Obligations Under Extraordinary InflationLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Can You Find The Names of 25 Books of The Bible in This ParagraphDocument1 pageCan You Find The Names of 25 Books of The Bible in This ParagraphLady BancudNo ratings yet

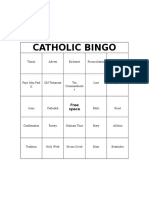

- Catholic Bingo: Trinity Advent Eucharist Reconciliation ApostlesDocument7 pagesCatholic Bingo: Trinity Advent Eucharist Reconciliation ApostlesLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Compensation in The Extinguishment of An ObligationDocument2 pagesFundamentals of Compensation in The Extinguishment of An ObligationLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Dermaline, Inc. vs. Myra Pharmaceuticals, Inc., GR No. 190065, August 16, 2010Document6 pagesDermaline, Inc. vs. Myra Pharmaceuticals, Inc., GR No. 190065, August 16, 2010Lady BancudNo ratings yet

- Pearl & Dean (Phil.), Inc. v. Shoemart, Inc. and North Edsa Marketing, Inc. G.R. No. 148222, August 15, 2003 Corona, J. FactsDocument4 pagesPearl & Dean (Phil.), Inc. v. Shoemart, Inc. and North Edsa Marketing, Inc. G.R. No. 148222, August 15, 2003 Corona, J. FactsLady BancudNo ratings yet

- ContractsDocument1 pageContractsLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Additional Cases DigestsDocument8 pagesAdditional Cases DigestsLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Obligations Nature and Effects of ObligationsDocument56 pagesObligations Nature and Effects of ObligationsLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Consolidated IPL (PG 10-18)Document23 pagesConsolidated IPL (PG 10-18)Lady BancudNo ratings yet

- TORRES VsDocument1 pageTORRES VsLady BancudNo ratings yet

- ICERDDocument6 pagesICERDLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Disposition of Obligations Under Extraordinary InflationDocument2 pagesDisposition of Obligations Under Extraordinary InflationLady BancudNo ratings yet

- SAMSON V. CABANOS 2005Document3 pagesSAMSON V. CABANOS 2005Lady BancudNo ratings yet

- Obli Statute of FraudsDocument11 pagesObli Statute of FraudsLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Municipal Court Ruling on Contract Dispute and Writ of AttachmentDocument14 pagesMunicipal Court Ruling on Contract Dispute and Writ of AttachmentLady BancudNo ratings yet

- CEMBRANO VS. CITY OF BUTUAN - Payment to Wrong Party Does Not Extinguish ObligationDocument2 pagesCEMBRANO VS. CITY OF BUTUAN - Payment to Wrong Party Does Not Extinguish ObligationLady Bancud100% (1)

- Batch 2 #S 59 and 60Document3 pagesBatch 2 #S 59 and 60Wsrc SmrNo ratings yet

- Cheryl 19-21Document6 pagesCheryl 19-21Lady BancudNo ratings yet

- Unno Commercial Enterprises and Societe-2Document3 pagesUnno Commercial Enterprises and Societe-2Lady BancudNo ratings yet

- Lacoste vs. Fernandez: Unfair Competition in Trademark RegistrationDocument2 pagesLacoste vs. Fernandez: Unfair Competition in Trademark RegistrationLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Tet Dillera - #4-6 - Mirpuri To Philip MorrisDocument5 pagesTet Dillera - #4-6 - Mirpuri To Philip MorrisLady BancudNo ratings yet

- Bancud 49,50,51Document3 pagesBancud 49,50,51Lady BancudNo ratings yet

- Philippine trademark cases on similarity, goodwill and mootnessDocument3 pagesPhilippine trademark cases on similarity, goodwill and mootnessLady BancudNo ratings yet

- ARTICLE 33 and 36 MANOLO P. SAMSON, Petitioners, v. CATERPILLAR, INC., Respondent. Decision Austria-Martinez, J.Document20 pagesARTICLE 33 and 36 MANOLO P. SAMSON, Petitioners, v. CATERPILLAR, INC., Respondent. Decision Austria-Martinez, J.tink echivereNo ratings yet

- The Law of Partnership Is An Extention of Law of AgencyDocument22 pagesThe Law of Partnership Is An Extention of Law of AgencyNominee Pareek50% (4)

- Hiew Min ChungDocument9 pagesHiew Min ChungChin Kuen YeiNo ratings yet

- (HC) (2015) 7 MLJ 305 - Universal Trustee (M) BHD V Lambang Pertama SDN BHD & AnorDocument11 pages(HC) (2015) 7 MLJ 305 - Universal Trustee (M) BHD V Lambang Pertama SDN BHD & AnorAlae KieferNo ratings yet

- Philippine Supreme Court rules bank's possession of pledged vessels lawfulDocument14 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court rules bank's possession of pledged vessels lawfulpatrixiaNo ratings yet

- Sanico V ColipanoDocument3 pagesSanico V ColipanoMarlon GarciaNo ratings yet

- Insurance Dispute Over Destroyed GoodsDocument56 pagesInsurance Dispute Over Destroyed GoodsKristabelleCapaNo ratings yet

- Gutierrez v. The House of Representatives Committee On Justice, G.R. No. 193459, 15 Feb 2011 PDFDocument91 pagesGutierrez v. The House of Representatives Committee On Justice, G.R. No. 193459, 15 Feb 2011 PDFGab EstiadaNo ratings yet

- AMLA 4 PDIC V Gidwani GR 234616 PDFDocument17 pagesAMLA 4 PDIC V Gidwani GR 234616 PDFMARIA KATHLYN DACUDAONo ratings yet

- Siok Ping Tang Vs SubicDocument2 pagesSiok Ping Tang Vs SubicTristan HaoNo ratings yet

- de Dios Vs CaDocument7 pagesde Dios Vs CalewildaleNo ratings yet

- Workmen's Compensation Case Determines Statutory EmployerDocument124 pagesWorkmen's Compensation Case Determines Statutory EmployerScpo Presinto DosNo ratings yet

- R110 Prosecution of OffensesDocument3 pagesR110 Prosecution of OffensesRafaela SironNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument17 pagesProjectHera Fatima NaqviNo ratings yet

- 525A CJ2 Performance TablesDocument20 pages525A CJ2 Performance TablesErnani L AssisNo ratings yet

- Fores vs. MirandaDocument6 pagesFores vs. Mirandakizh5mytNo ratings yet

- Rules 6 10Document77 pagesRules 6 10cmv mendozaNo ratings yet