Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal Tipus

Uploaded by

Devi DamayantiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jurnal Tipus

Uploaded by

Devi DamayantiCopyright:

Available Formats

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS)

Author: Professor Jaime Campos-Castell1

Creation Date: March 2003

Update: September 2004

Scientific Editor: Professor Jacques Motte

1

Departmento de Pediatria, Servicio de Neurologia, Hospital clinica de San Carlos, Calle Profesor Martin

Lagos, S/N, 28040 Madrid, Spain.

Abstract

Key-words

Disease name and synonymes

Excluded diseases

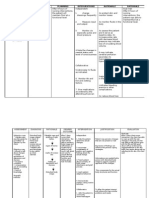

Diagnostic criteria / definition

Differential diagnosis

Frequency

Clinical description

Management including treatment

Etiology

Diagnostic methods

Genetic counselling

Unresolved questions

References

Abstract

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) belongs to the group of severe childhood epileptic encephalopathies.

This disorder is defined as a cryptogenic or symptomatic generalized epilepsy, which is characterized by

the following symptomatic triad: several epileptic seizures (atypical absences, axial tonic seizures and

sudden atonic or myoclonic falls); diffuse slow interictal spike wave in the waking electroencephalogram

(EEG) (< 3 Hz) and fast rhythmic bursts (10 Hz) during sleep; slow mental development associated with

personality disturbances. Incidence is estimated to 1:1,000,000 inhabitants per year, and the prevalence

to 5-10% of epileptic patients, representing 1-2% of all childhood epilepsies. The onset occurs between 2

and 7 years. The most characteristic clinical manifestations in LGS consist of tonic seizures (17-92%),

atonic seizures (26-56%) and atypical absences (20-65%). Diagnosis is based on the presence of specific

EEG recordings. Treatment is difficult as LGS is usually refractory to conventional therapy. Some of the

new antiepileptic drugs (AED) (Felbamate, Lamotrigine, Topiramate) have proven efficient in the control of

seizures in LGS. The symptoms in cryptogenic LGS forms (20-30%) appear without antecedent history or

evidence of brain pathology, whereas symptomatic LGS cases (30-75%) are associated with pre-existent

brain damage.

Keywords

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS), childhood epileptic encephalopathies, tonic seizures, EEG recordings,

new antiepileptic drugs (AED)

Disease name and synonyms

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS)

Historical overview

In 1938, Gibbs et al. described the characteristic

EEG pattern of spikes and slow frequency

waves and proposed the term of petit mal

Campos-Castell J. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Orphanet Encyclopedia. September 2004

.http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/GB/uk-Lennox.pdf

variant to differentiate it from the petit mal

absence seizures associated with rhythmic

spike-and-waves (1). In 1950, Lennox and Davis

found clinical correlation between this type of

EEG and patients with multiple epileptic crisis

(2). Based upon the contributions of Lennox and

colleagues, Gastaut (3) and Dravet and

colleagues of the Marseille school, the term

"Lennox-Gastaut

Syndrome"

(LGS)

was

adopted.

Diagnosis criteria / definition

LGS belongs to the group of severe infantile

epileptic

syndromes

(epileptic

neonatal

encephalopathy with suppression-burst, West

syndrome, severe myoclonic epilepsy of

infancy), which represent the most distressing

epileptic encephalopathies of infancy. LGS is

characterized by the following symptomatic triad:

several epileptic seizures (atypical absences,

axial tonic seizures and sudden atonic or

myoclonic falls); diffuse slow interictal spike

wave in the waking EEG (<3 Hz) and fast

rhythmic bursts (10 Hz) during sleep; slow

mental development associated with personality

disturbances.

Although this last element is not indispensable

for the diagnosis, it is manifested in a high

percentage of cases (4).

LGS is a controversial entity due to the difficulty

of establishing its semiological electroclinical

features and some authors have considered that

severe cases of myoclonic astatic epilepsy

represent myoclonic variants of LGS (4; 5).

However the myoclonic phenomenon is not

predominant in LGS, and this review focuses

only on Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, as strictly

defined above.

LGS is defined by the International Classification

of Epilepsies, Epileptic Syndromes, and Related

Seizure Disorders as a cryptogenic or

symptomatic generalized epilepsy (6).

Differential diagnosis

All the epilepsies with frequent and brief seizures

occurring in childhood should be eliminated from

differential diagnosis:

Myoclonic epilepsies

- Benign atypical partial epilepsy of the childhood

- Partial post-traumatic epilepsy with slow spikewave

- ESES syndrome

- Rett syndrome

- Angelman syndrome

Epilepsy absence with tonic or atonic

component.

Landau-Kleffner syndrome

Multifocal severe epilepsy

Ceroid-lipofuscinosis

Gobbi syndrome (epilepsy, celiac

disease and occipital calcifications)

Epidemiology

Although the incidence is estimated to 0.1 in

100.000 inhabitants per year, the prevalence is

high (5-10% of epileptic patients), representing

1-2% of all childhood epilepsies. The onset

occurs between 2 and 7 years. Cryptogenic

cases have a later onset (7). Males seem to be

more frequently affected. No family cases of

LGS have been reported.

Clinical description

The most characteristic clinical manifestations in

LGS (4, 8) consist of:

Tonic seizures, the most frequent finding

(1792%), occurring especially during

the slow sleep and never in the rapid

eye movement (REM) phase. Duration is

from a few seconds to a minute.

Seizures can be tonic-axial, proximal

appendicular or global. They are

accompanied with apnoea and facial

flushing, and they may lead to sudden

falling if they appear when patient is

awake.

Atonic

seizures

(2656%)

are

characterized by sudden loss of tone

that either involve the head or the whole

body. They can be very brief and may

be associated with myoclonic seizures at

the beginning of the crisis.

Atypical absences

(2065%)

are

associated with decrease or loss of

consciousness.

The

onset

and

termination are less abrupt than in

typical absence. Duration is from 5 to 30

seconds. These seizures are neither

induced by hyperventilation, nor by

photic stimulation.

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus has

been reported in two-thirds of the

patients, with duration ranging from

hours to weeks. The episodes may be

subtle and hardly noticeable. Tonic

status epilepticus appears frequently

following intravenous administration of

benzodiazepines.

Other seizure types, such as tonic-clonic

seizures,

clonic

seizures,

partial

seizures and spasms can sometimes be

observed, although they are not typical

of LGS.

Evolution

LGS, one of the most severe epileptic

syndromes in childhood, is refractory to

treatment and tends to become chronic. Mental

retardation, which is frequently associated with

the condition (9), especially in symptomatic

cases (10), tends to worsen as disease

progresses, although it is not the absolute rule.

Campos-Castell J. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Orphanet Encyclopedia. September 2004

.http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/GB/uk-Lennox.pdf

Psychosis may manifest during disease

evolution (8).

Patients with symptomatic LGS, especially with

pre-existent West syndrome, frequent seizures

and repeated episodes of status epilepticus,

have the worse prognosis.

The mortality rate is around 5%, but is rarely

bound to the evolution of the epilepsy itself, as

death is often related to accidents or episodes of

tonic status epilepticus.

Treatment

LGS is essentially characterized by a lack of

responsiveness to treatment, especially the

classic anti-epileptic drugs (AED) (11).

Barbiturates must be avoided as they

exacerbate seizures and also worsen the

behaviour of many patients. Bitherapy should be

preferred over polytherapy.

The association of valproic acid (VPA) and

benzodiazepines (specifically clobazam, in our

experience) is usually the first-line therapy for

most authors. The recommended doses are 20

40 mg/kg/day for valproic acid, and 0.51

mg/kg/day for clobazam.

Among the classic AED, phenytoin and

carbamazepine are effective on tonic and tonicoclonic seizures, but they can increase the other

types of seizures. Ethosuximide is useful in

some cases to control absences.

Some of the new AED have proven efficiency in

the control of LGS in clinical add-on trials.

Felbamate has been reported to control 8% of

seizures and to reduce 50% of all seizures type

in 50% of patients treated. However, as this drug

is associated with severe adverse side effects, it

is important to weigh benefits versus risks.

Lamotrigine has also shown a significant effect

in multicentric studies (12), with at least a 50%

reduction in seizure frequency in 32% of the

cases. When associated with VPA, this drug

should be introduced slowly at low initial dose to

prevent serious rash. Topiramate has also been

shown effective (13, 14, 15), with a responder

rate of 55-85%, its effects on atonic seizures

(suppression rate of 15%) being of special

interest. Preliminary studies suggest that

levetiracetam as add-on therapy appeared

effective in reducing atonic and tonic-clonic

seizures in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome seizures

(16, 17) ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) or

corticosteroids treatment (for up to four months)

may be helpful in LGS not responding to

therapy, although it may induce a Cushings

syndrome.

Ketogenic diet has been used in intractable

infantile epilepsies (18) and we have had

positive results in LGS patients (19, 20). Control

of all seizure types improved the first days after

the beginning of this therapy, but this diet

requires very strict compliance.

Barbiturate anesthesia is generally used in the

treatment of status epilepticus; a 5-day treatment

under these conditions proved a significant

improvement of seizures, but long term results

indicated that seizures recurred, and the number

of AEDs was significantly greater after than

before the anesthesia (21).

Clinical trials of intravenous immunoglobulins in

high doses have shown effectiveness in reduced

series.

Surgical treatment is an exceptional option in

cases of well-located lesions. Callosotomy has

been shown effective in intractable atonic

seizures, but it does not improve other seizure

types and the focal crises can even increase.

Presurgical study with PET allows to differentiate

four forms of SLG: cortical resections located in

cases of focal hypometabolism, hemisferectomy

and callosotomy in cases of unilateral diffuse

hypometabolism, callosotomy in bilateral diffuse

hypometabolism and abstention in cases without

demonstrable alteration.

Results of vagal stimulation in children with LGS

are difficult to evaluate because of the

methodology used in the published cases. A

serie showed an effectiveness limited in epileptic

encephalopathy (22). Another study reported

effective long-term results (over 5 years) with

50% reduction of seizures and with restricted

adverse side effects (23).

In any event, treatment of LGS should minimise

seizures and maximise quality of life, since the

last studies on the syndrome outcome maintain

bad prognosis in LGS (24), even when using

stringent criteria in defining the cryptogenic LGS

subgroups (25).

Etiology

In the cryptogenic forms (2030%), symptoms

appear without antecedent history or evidence of

brain pathology, but dendrites alterations have

been described in some of them (26). The

symptomatic cases (3075%) are associated

with perinatal asphyxia, tuberous sclerosis,

meningoencephalitis

sequelae,

cortical

dysplasia, cranial trauma and more rarely,

tumours and metabolic dysfunction. Some

idiopathic cases have been described (5%) to be

not associated with mental retardation or

neurological signs, normal neuroimaging, family

antecedents of epilepsy and genetic features in

the EEG studies.

Diagnostic methods

The hallmark of the awake interictal EEG in

patients with LGS is the diffuse slow spike wave

pattern (equal or inferior tp 2.5 Hz) (8, ). The

epileptiform discharges last from several minutes

to a near continuous state, they are prevalent in

frontal regions, and asymmetric in 25% of cases.

Campos-Castell J. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Orphanet Encyclopedia. September 2004

.http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/GB/uk-Lennox.pdf

Spike discharges at 10 Hz lasting 1 to 10

seconds are common during non-REM sleep.

The ictal EEG depends on the seizure type. In

tonic seizures, the activity pattern consists of

diffuse, rapid (1025 Hz), and bilateral

discharges in the anterior or vertex areas. During

atonic seizures, the EEG shows slow spike

waves and fast-recruiting discharges. Myoclonic

seizures are characterized by synchronous and

symmetrical spike and sharp waves of brief

duration, followed by one or several slow waves.

References

1. Gibbs FA, Gibbs EL, Lennox WG. Influence of

blood sugar level on wave and spikes formation

in petit mal epilepsy. Arch Neurol Psychiatry

1939; 41:1111-1116.

2. Lennox WG, Davis JP. Clinical correlates of

the

fast

and

the

slow

spikes-wave

electroencephalogram. Pediatrics 1950; 5:626644.

3. Gastaut H, Roger J, Soulayrol R, Tassinari C,

Regis H, Dravet C, Bernard R, Pinsard N, SaintJean M. Childhood epileptic encephalopathy with

diffuse slow spike-waves (otherwise known as

petit mal variant) or Lennox syndrome.

Epilepsia 1966, 7:139-179.

4. Aicardi J. The problem of Lennox syndrome.

Dev Med Child Neurol 1973, 15:77-81.

5. Aicardi J. Epilepsy in children. In LennoxGastaut Syndrome 2nd Ed. pp. 44-66. Raven

Press, New York, 1994.

6.

Commission

on

Classification

and

Terminology of the International League Against

Epilepsy: Proposal for Revised Classification of

Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes. Epilepsia

1989, 30:389-399.

7. Oller Daurella L. Sndrome de LennoxGastaut, pp. 128. Ed. Espaxs, Barcelona, 1967.

8. Beaumanoir A, Dravet C. The Lennox-Gastaut

syndrome. In Epileptic Syndromes in Infancy,

Childhood and Adolescence, 2nd. Ed. Roger J,

Bureau M, Dravet C et al. pp. 115-132. John

Libbey, London, 1992.

9. Oller-Daurella L, Oller Ferrer-Vidal L, Sanchez

ME. Evolucin del sndrome de Lennox-Gastaut.

Rev Neurol (Barcelona), 1985; 63:169-184.

10. Oguni H, Hayashi K, Osawa M. Long term

prognosis

of

Lennox-Gastaut

syndrome.

Epilepsia 1996; 37:44-47.

11. J. A. French, A. M. Kanner, J. Bautista, B.

Abou-Khalil, T. Browne, C. L. Harden, W. H. et

al. Efficacy and tolerability of the new

antiepileptic drugs II: Treatment of refractory

epilepsy: Report of the Therapeutics and

Technology Assessment Subcommittee and

Quality Standards Subcommittee of the

American Academy of Neurology and the

American Epilepsy Society. Neurology, 2004; 62:

1261 - 1273.

12. Motte J, Trevathan E, Arvidson JFV, Nieto

M, Mullens EL, Manasco P, and the Lamictal

Lennox-Gastaut Study Group. Lamotrigine for

generalized seizures associated with the

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. N Engl J Med 1997,

337:1807-1812.

13. Herranz JL, Arteaga R. Eficacia y

tolerabilidad del topiramato a largo plazo en 44

nios con epilepsias rebeldes. Rev Neurol 1999;

28:1049-1053.

14. Glauser TA, Levisohn PM, Ritter F, Sachdeo

RC. Topiramate in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome:

open label treatment of patients completing a

randomized controlled trial. Topiramate study

Group. Epilepsia 2000, 41 (suppl 1): S 86-90.

15. Glauser TA. Topiramate in the catastrophic

epilepsies of childhood. J Child Neurol 2000; 15:

S14-S21.

16. De Los Reyes EC, Sharp GB, Williams JP,

Hale SE. Levetiracetam in the treatment of

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Pediatr Neurol.

2004;30:254-6.

17. Huber B, Bommel W, Hauser I, Horstmann

V, Liem S, May T, Meinert T, Robertson E,

Schulz L, Seidel M, Tomka-Hoffmeister M,

Wagner W. Efficacy and tolerability of

levetiracetam in patients with therapy-resistant

epilepsy and learning disabilities. Seizure.

2004;13:168-75.

18. Huttenlocher PR, Wilbourn AJ, Signore JM.

Medium-chain triglycerides as a therapy for

intractable childhood epilepsy. Neurology, 1971,

21:1097-1103.

19. Prats Vias JM, Madoz P, Martin R.

Triglicridos de cadena media en la epilepsia

infantil teraputicamente rebelde. Rev Esp Ped

1976, 187:111-122.

20. Calandre L, Martnez-Martn P, Campos

Castell J. Tratamiento del sndrome de Lennox

con triglicridos de cadena media. Anales

Espaoles de Pediatra, 1978; 11:189-194.

21. Rantala H, Saukkonen AL, Remes M, Uhari

M. Efficacy of five days anesthesia in the

treatment of intractable epilepsies in children.

Epilepsia, 1999, 40:1775-1779.

22. Parker APJ, Polkey CE, Binnie CD, Madigan

C, Ferrie CD, Robinson RO. Vagal nerve

stimulation in epileptic encephalopathies.

Pediatrics 1999; 103:778-782.

23. Ben-Menachem E, Hellstrom K, Waldton C,

Augustinssen LE. Evaluation of refractory

epilepsy treated with vagus nerve stimulation for

up to 5 years. Neurology, 1999, 52:1265-1267.

24. Rantala H, Putkonen T. Occurence,

Outcome and prognostic factors of infantile

spasms

and

Lennox-Gastaut

syndrome.

Epilepsia, 1999, 40:286-289.

25. Goldsmith IL, Zupano ML, Buchhalter JR.

Long-term seizure outcome in 74 patients with

Lennox-Gastaut

syndrome:

effects

of

incorporating MRI head imaging in defining the

Campos-Castell J. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Orphanet Encyclopedia. September 2004

.http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/GB/uk-Lennox.pdf

cryptogenic subgroup. Epilepsia 2000, 41:395399.

26. Nieto Barrera M. Encefalopatas epilpticas

infantiles inespecficas. Monografa Roche.

1978. Karbowski K, Vassella F, Schneider H.

Electroencephalographic aspects of Lennox

syndrome. Europ Neurol 1970, 4:301-311.

Campos-Castell J. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Orphanet Encyclopedia. September 2004

.http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/GB/uk-Lennox.pdf

You might also like

- Leaf LeadDocument1 pageLeaf LeadDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Leaf Lead TB 2Document1 pageLeaf Lead TB 2Devi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Dokumentasi HeDocument1 pageDokumentasi HeDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anastesi PDFDocument292 pagesJurnal Anastesi PDFFatimah alhabsyieNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anastesi PDFDocument292 pagesJurnal Anastesi PDFFatimah alhabsyieNo ratings yet

- Herpes Zoster-Predicting and Minimizing The Impact of Post-Herpetic NeuralgiaDocument8 pagesHerpes Zoster-Predicting and Minimizing The Impact of Post-Herpetic NeuralgiaDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- PR104 FS LGS Atd 10.20.11 PDFDocument3 pagesPR104 FS LGS Atd 10.20.11 PDFDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anastesi PDFDocument292 pagesJurnal Anastesi PDFFatimah alhabsyieNo ratings yet

- PR104 FS LGS Atd 10.20.11 PDFDocument3 pagesPR104 FS LGS Atd 10.20.11 PDFDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Bio AnalyticalDocument8 pagesBio AnalyticalIkaNurMasrurohNo ratings yet

- Treatment Atrophic Facial AcneDocument5 pagesTreatment Atrophic Facial AcneDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Gambaran Kadar Kolesterol, Albumin Dan Sedimen Urin Penderita Anak Sindroma NefrotikDocument4 pagesGambaran Kadar Kolesterol, Albumin Dan Sedimen Urin Penderita Anak Sindroma NefrotikToko JamuNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Guide en PDFDocument58 pagesAnxiety Guide en PDFDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Antidepressant Discontinuation SyndromeDocument26 pagesAntidepressant Discontinuation SyndromeDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- AnginaDocument8 pagesAnginaWwwanand111No ratings yet

- Referensi ReferatDocument8 pagesReferensi ReferatDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- HistoDocument2 pagesHistoDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Population/problem Intervention Comparative/control: Pemberian Chlorampenicol 500mg OutcomeDocument6 pagesPopulation/problem Intervention Comparative/control: Pemberian Chlorampenicol 500mg OutcomeDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- QPostHerpeticNeauralgia NSinghDocument3 pagesQPostHerpeticNeauralgia NSinghDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Exclusive Breastfeeding Reduces Acute Respiratory Infection and Diarrhea Deaths Among Infants in Dhaka SlumsDocument1 pageExclusive Breastfeeding Reduces Acute Respiratory Infection and Diarrhea Deaths Among Infants in Dhaka SlumsDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Cohen 2007 Stress and DiseaseDocument3 pagesCohen 2007 Stress and DiseaseBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Petunjuk Prakt Blok 21 DosisDocument11 pagesPetunjuk Prakt Blok 21 DosisDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Petunjuk Prakt Blok 21 DosisDocument11 pagesPetunjuk Prakt Blok 21 DosisDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- 529 536Document13 pages529 536Devi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Banmal Song Lyrics and ChordDocument6 pagesBanmal Song Lyrics and ChordDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- HTTP WWW - MedscapeDocument3 pagesHTTP WWW - MedscapeDevi DamayantiNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Postop Actual &potential NCPDocument12 pagesPostop Actual &potential NCPJohn Paul Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Ayva Içerik Cydonia Oblonga PDFDocument20 pagesAyva Içerik Cydonia Oblonga PDFZeynep Emirhan ŞenyüzNo ratings yet

- Annual Review of Selected ScientificDocument50 pagesAnnual Review of Selected Scientificpasber26No ratings yet

- 06 HEALTH TALK ImmunizationDocument18 pages06 HEALTH TALK Immunizationamit100% (3)

- Case Study: Vascular V12Document12 pagesCase Study: Vascular V12biomedical_com_brNo ratings yet

- Morquio Syndrome Research ProjectDocument1 pageMorquio Syndrome Research Projectapi-233837066No ratings yet

- Abu Dhabi Emirate Environment, Health & Safety Management System Technical Guideline - Safety in Heat (V2.1) 2013Document24 pagesAbu Dhabi Emirate Environment, Health & Safety Management System Technical Guideline - Safety in Heat (V2.1) 2013Clifford Juan CorreaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Andrei Manu-Marin's Guide to the Urinary MicrobiomeDocument12 pagesDr. Andrei Manu-Marin's Guide to the Urinary MicrobiomeKINETO62No ratings yet

- Clinical Approach To Brainstem LesionsDocument10 pagesClinical Approach To Brainstem LesionsJosé SánchezNo ratings yet

- Medici Di Makati College 1061 Metropolitan Avenue, San Antonio Village, Makati City, Philippines 1200Document18 pagesMedici Di Makati College 1061 Metropolitan Avenue, San Antonio Village, Makati City, Philippines 1200Andee SalegonNo ratings yet

- Screening For DiseaseDocument29 pagesScreening For DiseaseSrinidhi Nandhini Pandian100% (2)

- Ophthalmology - Diseases of The EyelidsDocument9 pagesOphthalmology - Diseases of The EyelidsjbtcmdtjjvNo ratings yet

- Rekap BPJS Ri 2015 UpdateDocument373 pagesRekap BPJS Ri 2015 UpdateA- RONIENo ratings yet

- Bam Slam Drug CardDocument4 pagesBam Slam Drug CardLeticia GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Chocolate and The Brain: Neurobiological Impact of Cocoa Flavanols On Cognition and BehaviorDocument9 pagesChocolate and The Brain: Neurobiological Impact of Cocoa Flavanols On Cognition and BehaviorStefan AvramovskiNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Earlyr' Epidemic Model and Time Series Model For Prediction of COVID-19 Registered CasesDocument8 pagesAnalysis of Earlyr' Epidemic Model and Time Series Model For Prediction of COVID-19 Registered CaseskkarthiksNo ratings yet

- 50 Cardiology Pimp QuestionsDocument19 pages50 Cardiology Pimp Questionstrail 1No ratings yet

- NCCAOM-Indications-of-162-FormulasDocument6 pagesNCCAOM-Indications-of-162-FormulasEdison halimNo ratings yet

- Esmr 2Document1 pageEsmr 2Martina FitriaNo ratings yet

- Granulomatous Mastitis - A Case ReportDocument3 pagesGranulomatous Mastitis - A Case ReportqalbiNo ratings yet

- Medical EmergenciesDocument3 pagesMedical Emergencieskiranvarma2uNo ratings yet

- Conjunctivitis Guide: Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentDocument77 pagesConjunctivitis Guide: Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentJade MonrealNo ratings yet

- Reading Plus Unit 1Document27 pagesReading Plus Unit 1Anonymous SFTeXFdnNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Selection in SepsisDocument4 pagesAntibiotic Selection in SepsisIndah AmisaniNo ratings yet

- OET Writing Review NotesDocument13 pagesOET Writing Review NotesMohamed SakrNo ratings yet

- DK Chakra Chart 2017Document2 pagesDK Chakra Chart 2017Tuxita SuryaNo ratings yet

- 13 I can talk about health issuesDocument2 pages13 I can talk about health issuesHuy NguyenNo ratings yet

- National pediatric evaluationDocument8 pagesNational pediatric evaluationMaya Susanti100% (1)

- Rule of 4 Explains Brainstem LesionsDocument3 pagesRule of 4 Explains Brainstem Lesionsashr9No ratings yet

- Resort To Faith Healing Practices in The Pathway To Care For Mental Illness A Study On Psychiatric Inpatients in OrissaDocument13 pagesResort To Faith Healing Practices in The Pathway To Care For Mental Illness A Study On Psychiatric Inpatients in OrissaGuilherme Alves PereiraNo ratings yet