Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ESCO Review

Uploaded by

Tim Knauss0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11K views8 pagesNY Public Service Commission document.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentNY Public Service Commission document.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11K views8 pagesESCO Review

Uploaded by

Tim KnaussNY Public Service Commission document.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

STATE OF NEW YORK

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION

CASE 15-M-0127 - In the Matter of Eligibility Criteria for Energy

Service Companies.

CASE 12-M-0476 - Proceeding on Motion of the Commission to Assess

Certain Aspects of the Residential and Small

Non-residential Retail Energy Markets in New

York State.

CASE 98-M-1343 - In the Matter of Retail Access Business Rules.

NOTICE OF EVIDENTIARY AND COLLABORATIVE TRACKS

AND DEADLINE FOR INITIAL TESTIMONY AND EXHIBITS

(Issued December 2, 2016)

When the Commission first opened up the energy

services market to retail competition, the intended purpose of

allowing Energy Service Companies (ESCOs) to serve residential

and small non-residential customers (mass-market customers) was

to spur innovation in the creation of value-added products,

particularly energy efficiency services that regulated rates may

not provide, and to create commodity price competition that

would result in efficiencies.

It was believed that robust

competition would result in efficiencies that would be

beneficial to customers and would produce just and reasonable

rates for commodity service better than would monopoly

regulation.

The Commission accordingly exercised its ratemaking

authority to effectuate competitive access to utility systems by

unbundling utility rates into monopoly (transport) and

competitive (energy commodity) portions.

The Commissions

planned policy of regulatory forbearance, under which market

pressures set rates for competitive electric commodity

suppliers, was upheld based on continued Commission oversight of

CASES 15-M-0127 et al.

the commodity market to ensure that market rates were just and

reasonable.1

Although often necessary, the regulation of monopoly

services can be imperfect, administratively burdensome and

untimely, and can lead to inefficient pricing.

Competitive

markets tend to efficiently distribute and allocate resources in

society because customers consider their own benefit when

choosing how much to consume or to pay for a good or service.

The actions of such consumers in a functioning competitive

market generally drive prices to a state where marginal benefits

equal marginal costs, since customers are not willing to

purposefully pay any more than the minimum necessary to obtain

the benefits they desire.

Similarly, competitive markets tend

to be efficient at encouraging sellers to produce goods and

services for the lowest cost so as not to lose market share to

their competitors.

Robust competitive markets typically have

the following characteristics:

(1) sufficiently large enough

number of buyers and sellers to prevent individuals or groups

from exclusively influencing the market price; (2) products that

can be readily compared; (3) complete information about prices

and supplies for both producers and consumers; (4) sellers that

face significant elasticity of demand around the market price

such that, if a seller charges a higher price, demand will

significantly drop because buyers will switch suppliers, and if

a seller charges a lower price (below market cost), it will

receive significantly less net revenue than if it charged the

market price; and (5) few barriers to entry to the market for

both buyers and sellers.

Matter of Energy Assn. of New York State v Public Serv. Commn.

of the State of N.Y., 169 Misc. 2d 924, 936-37 (Albany County

1996), affd on other grounds, 273 A.D. 2d 708 (3d Dept 2000).

-2-

CASES 15-M-0127 et al.

After considerable experience with the offering of

retail service to mass market customers by ESCOs, the Commission

has determined that the retail markets serving mass-market

customers are not providing sufficient competition or innovation

to properly serve consumers.2

Despite efforts to realign the

retail market,3 customer abuses and overcharging persist, and

there has been little innovation, particularly in the provision

of energy efficiency and energy management services.

Commodity

price differentiation has not worked, and the market for

differentiated services is immature or non-existent.

If ESCOs

were truly living up to the promise of their function as

innovators, it is expected that there would be much greater

variety and transparency in the market for goods and services

that supply real consumer energy value, insistence from serious

participants on rules that govern against consumer fraud,

maturity beyond door to door selling, and a consumer base with a

much greater degree of satisfaction.

While a well designed

market could offer these consumer opportunities, it simply does

not exist today.

Accordingly, the Commission continues to

examine measures that must be taken to ensure that these

customers receive valuable services and pay just and reasonable

rates for commodity and other services.

Among the measures to

be considered are: (a) whether ESCOs should be completely

prohibited from serving their current products to mass-market

customers; (b) whether the regulatory regime, rules and Uniform

2

Case 12-M-0476, et al., Retail Access, Order Taking Actions to

Improve the Residential and Small Non-residential Retail

Access Markets (issued February 25, 2014).

Case 12-M-0476, et al., supra, Order Granting and Denying

Petitions for Rehearing in Part (issued February 6, 2015); and

Case 15-M-0127, et al., Eligibility Criteria for Energy

Service Companies, Order Resetting Retail Energy Markets and

Establishing Further Process (issued February 23, 2016).

-3-

CASES 15-M-0127 et al.

Business Practices (UBP) applicable to ESCOs need to be modified

to implement such a prohibition, to provide sufficient

additional guidance as to acceptable rates and practices of

ESCOs, or to create enforcement mechanisms to deter customer

abuses and overcharging, including whether the Commission

decision not to subject ESCOs to Article 4 of the Public Service

Law should be revisited; and (c) whether new ESCO rules and

products can be developed that would provide sufficient real

value to mass-market customers such that new products could be

provided to them by ESCOs in the future in a manner that would

ensure just and reasonable rates.

Please take notice that in furtherance of these

efforts, two procedural tracks are established in these

proceedings for the consideration of measures "(a)", "(b)" and

"(c)" described above.

Track I shall be for the consideration

of measures "(a)" and "(b)" and shall include an evidentiary

hearing at which sworn testimony and exhibits will be subject to

cross-examination, followed by the filing of post-hearing briefs

prior to Commission action.

Track II shall be for the

consideration of measure "(c)" and shall include collaborative

meetings of interested parties, collaborative or party reports

or proposals, and the opportunity to comment in writing prior to

Commission action.

Please take further notice that Track I initial prefiled testimony and exhibits must be filed on or before April 7,

2017.

An Administrative Law Judge will be assigned to conduct

and oversee the evidentiary hearing process of Track I.

The

assigned Administrative Law Judge will work with the parties to

establish other Track I milestones and set the schedule for

them, including the date for the evidentiary hearing and the

schedule for post-hearing briefs.

-4-

CASES 15-M-0127 et al.

It is anticipated that Staff of the Department of

Public Service will provide testimony and exhibits in Track I

along with the testimony of ESCOs, regulated utilities, consumer

groups, and other interested parties.

All parties to these

proceedings may be subject to discovery regarding Track I

issues.

Parties submitting Track I testimony and exhibits

should address the following topics where relevant to their

positions:

1.

Whether ESCOs should be prohibited in total or in part

from serving their current products to mass-market

customers, or whether ESCOs should be required to offer

value-added energy efficiency and energy management

services as a condition to offering commodity services.

2.

Whether the regulatory regime of how the Commission

applies the Public Service Law to ESCOs should be modified

to ensure that customer abuses and overcharging by ESCOs

is deterred. In particular, the Commission has not

applied Article 4 to ESCOs, based on a construction that

Public Service Law 66(1) only applies to utilities with

plant in public streets.4 Is that construction justified

today? Would it be appropriate to revisit that

construction in light of subsequent events, such as the

adoption of the 2002 amendments to the Home Energy Fair

Practices Act? If the construction is revisited, would it

be appropriate and beneficial to customers and in the

public interest to apply the restrictions of Public

Service Law 65 to ESCOs?

3.

Whether the regulatory regime of how the Commission

applies the Public Service Law to ESCOs should be modified

to ensure adequate enforcement mechanisms, including

penalties, to deter customer abuses and overcharging. In

this regard, please comment on whether it is possible for

the Commission to seek penalties against ESCOs under the

current regime, pursuant to which they are only regarded

as gas and/or electric corporations under PSL Article

1, or if it is necessary to also regulate ESCOs under

Article 4 to seek penalties against ESCOs? If Article 4

Case 94-E-0952, Competitive Opportunities Regarding Electric

Service, Opinion No. 97-17 (issued November 18, 1997), mimeo

p. 34.

-5-

CASES 15-M-0127 et al.

regulation is deemed necessary, then what burdens would

such regulation impose? For instance, would it be

possible for ESCOs to obtain incidental regulation under

Public Service Law 66(13) and would such incidental

regulation serve the public interest? Would ESCOs also be

subject to undue burdens if they needed to obtain approval

for stock issuances under Public Service Law 69 or the

transfer of stocks, plant or franchises under Public

Service Law 70? Should ESCOs be further regulated as to

credit worthiness?

4.

Whether the regulatory regime of how the Commission

applies the Public Service Law to ESCOs should be modified

to guide ESCOs toward acceptable rates and practices and

deter customer abuses and overcharging. In particular, if

the Commission decides that Public Service Law Article 4

applies to ESCOs, should the Commission use the

discretionary authority of Public Service Law 66(12)(a)

to require filing of tariffs by ESCOs in order to ensure

that ESCO bills be no greater than utility bills? If so,

should the Commission require filing of tariffs by all

ESCOs, just ESCOs offering commodity-only service, or just

ESCOs that have been determined to charge prices in excess

of utility bills? Should the Commission take steps to

void existing ESCO contracts if it tariffs ESCO services?

5.

Whether the rules applicable to ESCOs should be modified

to ensure that customer abuses and overcharging by ESCOs

are deterred. If so, then should the authority be

imposition of Public Service Law Article 4 and/or other

requirements created by Public Service Law Article 6?

6.

Whether the Uniform Business Practices (UBP) applicable to

ESCOs should be modified to ensure that customer abuses

and overcharging by ESCOs are deterred.

7.

Whether door-to-door and outbound telemarketing practices

of ESCOs to mass market customers should be prohibited,

and whether other ESCO marketing practices should be

prohibited?

8.

Whether the purchases of receivables system regarding mass

market customers should be modified in any way, including

but not limited to imposing "purchase with recourse"

provisions or tiered discount rates so that ESCOs with

abusive practices bear more financial risk from such

practices?

-6-

CASES 15-M-0127 et al.

9.

The prices for retail gas and/or electric service charged

to and paid by mass-market customers of ESCOs in the

recent past, including, at a minimum, calendar years 2014

and 2015 and as much of 2016 as may be available, and the

prices those customers would have paid for comparable

utility service. If different products are offered (e.g.,

fixed vs. variable), the prices by product offering. In

addition to annual data, seasonal (summer and winter) and

monthly data should be provided where possible and

relevant. Data for residential and small commercial

customers should be provided separately. Data for

electric and natural gas products should be provided

separately. Where an ESCO product has been offered for

more than five years, the last five years of historical

data should be provided. Parties providing significant

quantities of data should consult with Staff as to

providing the data in a useful electronic format.

10. Data setting forth the number of customers served by

ESCOs, by ESCO, for 2014, 2015, and so much of 2016 as is

available.

11. Data setting forth the volume of sales in total dollars

and in kWh, by ESCO, for 2014, 2015, and so much of 2016

as is available.

12. Evidence that an ESCO has, in fact, in recent years

offered or is currently offering lower prices on an annual

basis compared to the incumbent utility consistently,

including number of customers served and total volume of

sales in both dollars and kWh. Such evidence should also

include an analysis of whether that price offering has

been profitable or resulted in a loss to the ESCO.

13. Whether, given the current retail market structure, it is

possible for an ESCO to profitably offer lower prices on

an annual basis compared to the incumbent utility

consistently and, if possible, how it can be done.

14. The number and nature of customer complaints regarding i)

retail prices and bills and ii) sales and marketing

practices from a) customers directly to ESCOs, b) from

customers to utilities about ESCOs, by ESCO, and c)

customers to the Commission about ESCOs, by ESCO during

calendar years 2014 and 2015 and as much of 2016 as it is

available.

15. ESCO marketing and sales practices, including printed

materials, customer contracts, scripts for telephone or

-7-

CASES 15-M-0127 et al.

door-to-door solicitations, and other training materials

for ESCO sales people for practices in effect during

calendar years 2014, 2015, and 2016. Such evidence should

include all efforts by ESCOs to ensure that they and their

personnel comply with the Uniform Business Practices (UBP)

and that they otherwise avoid any deceptive marketing

practices.

16. The ability of mass-market customers to obtain information

about relative prices and offerings of ESCOs and regulated

utilities and to understand such information, including

evidence regarding the transparency of the retail market

for mass-market customers and the level of knowledge in

that market.

17. Tools that are available in the public domain that

customers can use to do comparison shopping.

18. Specific customer surveys that shed light on customers

understanding about retail choices available and how to

make informed choices.

19. Actions by state agencies or consumer advocacy groups to

protect customers, to monitor the state of the retail

market customers, to provide information, or to lodge

complaints or impose discipline in the case of improper

ESCO practices, including specific concrete steps the

group has taken and any results obtained from those

actions.

20. Actions that have been taken or that could be taken to

strengthen the retail market or otherwise to provide

consumer protections sufficient to protect mass-market

customers from overcharges or deceptive marketing

practices. For instance, if the Commission decided to

subject ESCOs to Article 4 of the Public Service Law would

it be appropriate to require ESCOs to obtain Certificates

of Public Convenience and Necessity under Public Service

Law 68 in order to provide commodity service?

Track II activities shall be initiated by Staff of the

Department of Public Service upon notice to all parties in these

proceedings.

(SIGNED)

KATHLEEN H. BURGESS

Secretary

-8-

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Dispensers of CaliforniaDocument4 pagesDispensers of CaliforniaShweta GautamNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Costing Sheet Retail Price Calculation SheetDocument2 pagesCosting Sheet Retail Price Calculation SheetitskashifNo ratings yet

- Estee Lauder Beautiful Start Guide 2014Document165 pagesEstee Lauder Beautiful Start Guide 2014warpsbyherself100% (6)

- Sales FinalsDocument35 pagesSales FinalsJoesil Dianne100% (1)

- Caroline RegisDocument4 pagesCaroline RegisMayank SainiNo ratings yet

- Case Study Summary 1 SofameDocument2 pagesCase Study Summary 1 Sofameotma_rocks100% (2)

- The US Airline Industry Case Study SolutionDocument6 pagesThe US Airline Industry Case Study SolutionGourab Das80% (5)

- The FEIS Executive Summary of The I-81 Viaduct ProjectDocument42 pagesThe FEIS Executive Summary of The I-81 Viaduct ProjectNewsChannel 9No ratings yet

- 81 Travel Time EstimatesDocument6 pages81 Travel Time EstimatesTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- The FEIS Executive Summary of The I-81 Viaduct ProjectDocument42 pagesThe FEIS Executive Summary of The I-81 Viaduct ProjectNewsChannel 9No ratings yet

- National Grid Energy Vision NYDocument32 pagesNational Grid Energy Vision NYTim KnaussNo ratings yet

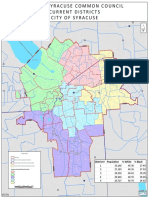

- Syracuse Council Districts MapDocument1 pageSyracuse Council Districts MapTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Rates by ZIP CodeDocument1 pageVaccination Rates by ZIP CodeTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Letter To President Biden On Ukraine RefugeesDocument1 pageLetter To President Biden On Ukraine RefugeesTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Destiny OffensesDocument1 pageDestiny OffensesTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- FAQ On COBRA SubsidyDocument10 pagesFAQ On COBRA SubsidyTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- 12 Worst DealsDocument17 pages12 Worst DealsTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Report of The County Executive 11-22-21Document1 pageReport of The County Executive 11-22-21Tim KnaussNo ratings yet

- B&L Sanitation Study 2.23.22Document12 pagesB&L Sanitation Study 2.23.22Tim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Onondaga County DecisionDocument15 pagesOnondaga County DecisionTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Attorney General James Releases Report On Nursing Homes' Response To COVID-19Document76 pagesAttorney General James Releases Report On Nursing Homes' Response To COVID-19News 8 WROCNo ratings yet

- TranscriptDocument3 pagesTranscriptNick Reisman100% (1)

- Assembly Senate Response.2.10.21. Final PDFDocument16 pagesAssembly Senate Response.2.10.21. Final PDFZacharyEJWilliamsNo ratings yet

- AEI Round 2 Allocation Recommendations ESDDocument3 pagesAEI Round 2 Allocation Recommendations ESDTim Knauss100% (2)

- Onondaga County Police Reform PlanDocument59 pagesOnondaga County Police Reform PlanTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Veto MSG BOE Pay CutDocument2 pagesVeto MSG BOE Pay CutTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- NYCLU Letter To OCSO Re COVID Restrictions at Justice Center - 12-24-2020Document3 pagesNYCLU Letter To OCSO Re COVID Restrictions at Justice Center - 12-24-2020Tim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Mayor Walsh Letter On Orange ZoneDocument2 pagesMayor Walsh Letter On Orange ZoneTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- DeWitt Warehouse EAFDocument48 pagesDeWitt Warehouse EAFTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Resolution To Roll Back Bail ReformDocument4 pagesResolution To Roll Back Bail ReformTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- LEO #19 (Signed) (37003)Document1 pageLEO #19 (Signed) (37003)Tim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Onondaga Zones OnlyDocument1 pageOnondaga Zones OnlyTim Knauss0% (1)

- Redistricting ResolutionDocument2 pagesRedistricting ResolutionTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- 2020 Poll Watcher Certificate GeneralDocument1 page2020 Poll Watcher Certificate GeneralTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- 138 Brownfield PropertiesDocument4 pages138 Brownfield PropertiesTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Ways & Means Budget ChangesDocument12 pagesWays & Means Budget ChangesTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Brownfield PropertiesDocument5 pagesBrownfield PropertiesTim KnaussNo ratings yet

- Example Single Product LTD: Required: (A) Calculate The FollowingDocument3 pagesExample Single Product LTD: Required: (A) Calculate The FollowingHamza0% (1)

- Zspeed Close Ratio Gear CatalogueDocument3 pagesZspeed Close Ratio Gear Catalogueapi-3863246100% (1)

- Future ContractsDocument25 pagesFuture ContractsvishalalluriNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Performance Based Assessment PDFDocument2 pagesModule 4 Performance Based Assessment PDFyojosukekonodiodaNo ratings yet

- CCD Vs StarbucksDocument27 pagesCCD Vs StarbucksMukesh Manwani100% (1)

- Members: Cristopher Peña Mario RojasDocument23 pagesMembers: Cristopher Peña Mario RojasAnonymous GB2pLzNo ratings yet

- Setup MYOB for Bookstore Company GRAMA, PTDocument6 pagesSetup MYOB for Bookstore Company GRAMA, PTGunawan Setio PurnomoNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From Ford Motor Company Business Plan - RestructuringDocument5 pagesExcerpt From Ford Motor Company Business Plan - RestructuringFord Motor Company50% (4)

- Rajasthan's Secondary Board's Free Laptop Distribution SchemeDocument68 pagesRajasthan's Secondary Board's Free Laptop Distribution Schemeneeraj meenaNo ratings yet

- Honduras EnvironmentDocument4 pagesHonduras EnvironmentInoue JpNo ratings yet

- A. & B. Beginning WIPDocument31 pagesA. & B. Beginning WIPChampy MadrigalNo ratings yet

- Vinod ResumeDocument3 pagesVinod ResumeVinod KumarNo ratings yet

- Ingersoll RandDocument2 pagesIngersoll RandAnkit AvishekNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice - Problems 1Document5 pagesMultiple Choice - Problems 1KatKat Olarte100% (1)

- Energy DerivativesDocument4 pagesEnergy DerivativesOliver ShiNo ratings yet

- Who Pays Report PDFDocument139 pagesWho Pays Report PDFChris JosephNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 Integrated Marketing CommunicationsDocument51 pagesChapter 16 Integrated Marketing CommunicationsMuhammad Ibrahim AbdullahNo ratings yet

- H-E-B Own Brands - Retail Case - 121590978Document21 pagesH-E-B Own Brands - Retail Case - 121590978Anuj SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Business Plan: Syed Asfandyar BanooriDocument11 pagesBusiness Plan: Syed Asfandyar BanooriAlllioNo ratings yet

- Cartelization in the Sugar IndustryDocument17 pagesCartelization in the Sugar IndustrySyed Umair JavaidNo ratings yet

- K. Simonds ResumeDocument2 pagesK. Simonds ResumeksimondsNo ratings yet

- Ajit NewspaperDocument27 pagesAjit NewspaperNadeem YousufNo ratings yet

- Castlegar - SlocanValley Pennywise April 29, 2014Document56 pagesCastlegar - SlocanValley Pennywise April 29, 2014Pennywise PublishingNo ratings yet