Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Peritonitis Anak

Uploaded by

Vhiena ShittaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Peritonitis Anak

Uploaded by

Vhiena ShittaCopyright:

Available Formats

Access this article online

Original Article

Website:

www.afrjpaedsurg.org

DOI:

10.4103/0189-6725.125429

PMID:

Role of damage control enterostomy in ***

Quick Response Code:

management of children with peritonitis

fromacute intestinal disease

Emmanuel A. Ameh, Michael A. Ayeni, Stephen A. Kache, Philip M. Mshelbwala

ABSTRACT and electrolyte balance, and stoma care, especially in

the first several days following surgery, are important

Background: Intestinal anastomosis in severely ill in preventing morbidity and mortality.

children with peritonitis from intestinal perforation,

intestinal gangrene or anastomotic dehiscence (acute Key words: Anastomotic dehiscence, damage

intestinal disease) is associated with high morbidity control, entetorostomy, intestinal gangrene,

and mortality. Enterostomy as a damage control intestinal perforation, peritonitis

measure may be an option to minimize the high

morbidity and mortality. This report evaluates the

role of damage control enterostomy in the treatment

of these patients. Materials and Methods: A

retrospective review of 52 children with acute intestinal INTRODUCTION

disease who had enterostomy as a damage control

measure in 12 years. Results: There were 34 (65.4%) The morbidity and mortality rate following intestinal

boys and 18 (34.6%) girls aged 3 days13 years resection and anastomosis in very ill patients, for

(median 9 months), comprising 27 (51.9%) neonates intestinal perforation or intestinal gangrene with

and infants and 25 (48.1%) older children. The primary

indication for enterostomy in neonates and infants was

peritonitis can be high in sub Saharan Africa,[1-3] with

intestinal gangrene 25 (92.6%) and perforated typhoid mortalities reaching 2656% in neonates and infants.[2,3]

ileitis 22 (88%) in older children. Enterostomy was Postoperative complications following anastomotic leak

performed as the initial surgery in 33 (63.5%) patients is also high especially in very ill patients. An alternative

and as a salvage procedure following anastomotic to intestinal anastomosis, in these situations, is the

dehiscence in 19 (36.5%) patients. Enterostomy-

creation of an enterostomy as a temporizing measure

related complications occurred in 19 (36.5%) patients,

including 11 (21.2%) patients with skin excoriations (damage control or salvage). Such use of enterostomy,

and eight (15.4%) with hypokalaemia. There were however, often generates controversy, especially in

four (7.7%) deaths (aged 19 days, 3 months, 3 children, due to apprehension that the enterostomy is

years and 10 years, respectively) directly related to difficult to manage particularly in settings with limited

the enterostomy, from hypokalaemia at 4, 12, 20 and resources.

28 days postoperatively, respectively. Twenty other

patients died shortly after surgery from their primary

disease. Twenty of 28 surviving patients have had

This report evaluates the role of enterostomy as a

their enterostomy closed without complications, while damage control measure in a selected group of children

eight are awaiting enterostomy closure. Conclusion: with intestinal perforation or gangrene in presence of

Damage-control enterostomy is useful in management peritonitis.

of severely ill children with intestinal perforation or

gangrene. Careful and meticulous attention to fluid

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In the period January 2000-November 2012, 52 severely

Department of Surgery, Division of Paediatric Surgery, Ahmadu Bello

University Teaching Hospital, Zaria, Nigeria ill children had damage control enterostomy for

This paper was presented in part at the 11th Annual Meeting and extensive peritonitis (faeces, pus or both) from acute

Scientific Conference of the Association of Paediatric Surgeons of intestinal disease (intestinal perforation, intestinal

Nigeria (APSON) in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, 22-24 September 2011. gangrene or dehiscence of an intestinal anastomosis) at

Address for correspondence: the Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Zaria,

Prof. Emmanuel A. Ameh,

Department of Surgery, PO Box 76, Zaria 810001, Nigeria. Nigeria. The hospital records of the patients have been

E-mail: eaameh@yahoo.co.uk retrospectively reviewed.

African Journal of Paediatric Surgery October-December 2013 / Vol 10 / Issue 4 315

Ameh, et al.: Peritonitis from acute intestinal disease in Children: Role of damage control enterostomy

Demographics, indications for surgery, location RESULTS

of enterostomy, post-operative complications and

outcome were retrieved from the patients case notes There were 34 boys (65.4%) and 18 girls (34.6%) aged

and operation notes. Decision to create an enterostomy 3 days13 years (median 9 months).

was taken if the child was critically ill, and there

was intraopereative finding of extensive peritoneal There were 27 neonates and infants aged <1 year

contamination with faeces or pus, grossly oedematous [Table 1]. The indications for enterostomy in these

intestine after resecting macroscopically diseased patients were gangrenous intussusceptions 13 (48.1%),

intestine, intestine of questionable viability or gangrene, intestinal malrotation with gangrenous midgut volvulus

or leaking/dehisced intestinal anastomosis. Following 12 (44.4%), intestinal atresia one (3.7%) and necrotising

enterostomy, the postoperative management protocol enterocolitis one (3.7%). In 22 (81.5%) of these patients,

included: enterostomy was a primary procedure and salvage

1. Fluid and electrolyte administration and procedure in five (18.5%). In 14 (51.9%) patients, the

stoma was sited in the ileum with mucus fistula in

monitoring: In addition to fluid maintenance,

colon, ileum alone in nine (33.3%) and in colon alone

ostomy effluent was replaced with appropriate

four (14.8%).

intravenous fluid while waiting for re-

establishment of bowel function; in the later part

Twenty one (77.8%) of these patients developed

of the study, in those with high ostomy effluent,

postoperative complications, nine (42.9%) of which

the proximal effluent was collected and infused

were directly related to the enterostomy procedure

into the distal stoma (mucus fistula), if there was (enterostomy related complication rate of 33.3%) and

no ileus. 12 (57.1%) related to the primary disease [Table 2].

2. Application of stoma appliance once proximal

stoma begins to function with monitoring of Fourteen (51.9%) of the patients in this age group

stoma effluent, application of barrier cream (zinc died, 12 died shortly after surgery from the primary

oxide or petroleum jelly) to the peri-stoma skin, disease and two deaths were related to the enterostomy

intravenous antibiotics administration and early procedure (these two deaths were aged 19 days and

and appropriate post-operative enteral nutrition as 3months and died from hypokalaemia after 4 and

the patients condition permitted. 12days, respectively).

There are two paediatric surgeons in this hospital There were 25 children aged one year and older.

and the decision to create a stoma is a division policy The indications for enterostomy in these patients

once the above mentioned conditions for creating an were typhoid ileal perforation 22 (88%), gangrenous

enterostomy were present. intussusceptions 2 (8%) and intestinal malrotation

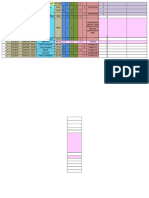

Table 1: Age and primary disease condition in 52 children requiring damage control enterostomy

Age (Years) Typhoid ileal Intussusception Intestinal malrotation Intestinal atresia Necrotizing Total (%)

perforation and midgut volvulus enterocolitis

<1month 7 1 1 9 (17.3)

<1 13 5 18 (34.4)

1-4 4 1 1 6 (11.5)

5-9 9 9 (17.3)

10+ 9 1 10 (19.2)

Total (%) 22 (42.3) 15 (28.8) 13 (25.0) 1 (1.9) 1 (1.9) 52 (100)

Table 2: Post-operative complications following enterostomy in 52 patients

Postoperative complications Age (Years) Total (%)

<1 month <1 1-4 5-9 10+ n=44

Related to primary disease 24 (54.5)

Septicaemia 4 4 1 4 1 14

Surgical site infections 4 1 3 2 10

Related to enterostomy 20 (45.4)

Skin excoriation 1 5 2 1 3 12

Hypokalaemia 1 2 1 2 2 8

316 October-December 2013 / Vol 10 / Issue 4 African Journal of Paediatric Surgery

Ameh, et al.: Peritonitis from acute intestinal disease in Children: Role of damage control enterostomy

with gangrenous midgut volvulus one (4%). In 14 that primary resection and anastomosis is growing in

(56%) patients, enterostomy was a salvage procedure popularity,[4] intestinal anastomosis in the presence of

and primary procedure in 11 (44%). The stoma was peritonitis has always been a surgical challenge. Various

sited in the ileum in 24 (96%) patients and colon in techniques have been devised to improve the safety,

one (4%). but all are fraught with dangers of leakage.[5] Several

factors affect the healing and success of an intestinal

Twenty three (92%) of the patients in this age group anastomosis include,[5,6] (a) well-nourished patient with

developed postoperative complications, 12 (52.2%) no systemic illness, (b) no faecal contamination either

of which were related to the primary procedure and within gut or in the surrounding peritoneal cavity,

11 (47.8%) were related to the enterostomy procedure (c)adequate exposure and access, (d) well-vascularised

(enterostomy related complication rate of 44%). tissues, (e) absence of tension at anastomosis and

(f)meticulous technique.

Ten (40%) of these patients died: Eight patients died

shortly after surgery from the primary disease and The leading primary indication for performing an

two deaths were directly related to the enterostomy enterostomy in the present report was peritonitis due

procedure (these were aged 3 years and 10 years, to typhoid perforation which is still prevalent in many

and died after 20 and 28 days, respectively, from developing countries.[2,7,8] Other indications for creating

hypokalaemia). an enterostomy were intussusception with gangrenous

intestine (29%), malrotation with intestinal gangrene

Overall, the primary condition warranting enterostomy associated with volvulus (19%) and to a lesser extent,

were mostly perforated typhoid ileitis 22 (42.3%), ileal atresia and necrotising enterocolitis. Infants with

intussusceptions with intestinal gangrene 15 (28.8%) intussusceptions in this setting often present late and

and intestinal malrotation with gangrenous midgut intestinal gangrene may warrant resection. Our previous

volvulus 13 (25%). experience[9] showed that anastomosis in these patients

often leak and when there is a leak, the risk of further

Overall, 14 of 33 (42.4%) patients, who had enterostomy leak is high if another resection and anastomosis is

as a primary procedure, died from the primary disease done.

and 10 of 19 patients who had enterostomy as a

salvage procedure following anastomotic dehiscence Anastomosis, in emergency surgery, as in the setting

died. Twenty four (46.2%) patients died (typhoid ileal of acute intestinal diseases, is often performed in

perforation 13, malrotation with gangrenous midgut critically ill patients under difficult situations. Some of

volvulus six, intussusceptions with intestinal gangrene the patients may be malnourished or have co-morbid

four and anorectal anomaly with ileal atresia one). conditions. Anastomotic leak rate following resection

Twenty (38.5%) mortalities were related to the primary and anastomosis vary from 10% to 42.8%.[3,5]

disease and four (7.7%) were directly related to the

enterostomy procedure. The logical use of enterostomy as a damage control

measure is based on the understanding of the

Of the 28 surviving patients, 20 have had their pathologic changes and perverted function present in

enterostomies closed after 8 weeks-10 months (median diseases associated with distension of the intestine,

6 months). There was no anostomotic leakage following whether from obstruction or peritonitis. In the present

ostomy closure in any of these patients and they have report, 64% (n = 33) had enterostomy performed as

remained well. Eight patients are awaiting closure of a primary procedure. Patients, who were critically

their stoma. ill with the finding of extensive faecal peritonitis,

grossly oedematous resected intestine, and intestine

DISCUSSION of questionable viability/blood supply, were given

enterostomy as a primary procedure. Enough blood

When there is intestinal gangrene and perforation in supply required to keep a segment of intestine viable

children, the decision to resect a diseased segment may not be adequate for healing of an anastomosis.

of intestine is usually straightforward. However, the The adequacy of blood supply to the intestines also

clinical decision to subsequently perform a primary depends on the haemodynamic status of the patient.

anastomosis or end colostomy/ileostomy or protect These points should be taken into consideration

a distal anastomosis with a defunctioning stoma is when deciding on the extent of resection when there

often more complicated. While most surgeons agree is intestinal gangrene and whether an intestinal

African Journal of Paediatric Surgery October-December 2013 / Vol 10 / Issue 4 317

Ameh, et al.: Peritonitis from acute intestinal disease in Children: Role of damage control enterostomy

anastomosis is safe or an enterostomy should included in the fluid management, if there are no

be done. Where conditions for safe anastomosis contraindications to potassium administration.

cannot be guaranteed, an enterostomy as a primary 2. Nutrition: Although parenteral nutrition is useful,

procedure should be done. One-third of the patient this is not readily available in this setting. We

in the present report had enterostomy as a salvage have relied largely on early enteral feeding (soon

procedure following anastomotic dehiscence. One as intestinal function returns) using protein-rich

report has noted a dramatic decrease in mortality from enteral diets. When the output is high, collecting

82.5% to 33.8% and later to 20% with enterostomy the proximal stoma effluent (without sterilisation)

in postoperative peritonitis after anastomotic and re-infusing it into the distal stoma (mucus

dehiscence.[12] fistula) was useful in a few patients. In one report,[11]

including children and adults, it was noted that it

Intestinal anastomosis may be unsafe in critically ill was not necessary to sterilize the effluent before

patients with peritonitis from intestinal perforation, reinfusion as the bacterial concentration of the re-

intestinal gangrene or anastomotic dehiscence. In this infused fluid averaged 105/ml. In another report[14]

scenario, damage control enterostomy is required. The of 30 patients with peritonitis and stoma or fistula,

surgical options for such enterostomy may include: re-infusion of proximal effluent into the distal

1. Exteriorisation of the bowel ends (proximal end intestine significantly reduced the proximal stoma

stoma and distal mucus fistula) after resecting the output. This can be useful in controlling fluid and

diseased segment. This was the choice in most of electrolyte loss, but we have only used this in a few

the patients in this report. patients.

2. Exteriorisation of the site of perforation (after 3. Peri-stoma skin care: In small bowel stomas,

excision of edges of the perforation to healthy peri-stoma skin excoriations can readily occur.

intestine) as a loop enterostomy. This was not used Its important that peri-stoma skin care begins

in the present report as the primary pathologies immediately after surgery to avoid the complication.

warranted resection of the diseased segment of In our setting, zinc oxide cream and petroleum

intestine. This option is most suitable in situations jelly were effective. After about 4-6 weeks, the risk

where the intestine adjacent to the perforation is of excoriation often reduces as the skin appears to

not significantly compromised. adapt but skin care must be maintained until the

3. A n a s t o m o t ic e n t e r o s t o m y : T h i s i n v o l v e s time of stoma closure.

exteriorisation of the anterior wall of a partially

dehisced anastomosis when up to 50% of the The overall complication rate in the present report was

circumference of the wall is intact (after excision high at 85%. Previous reports have noted a complication

of the devitalised edges). If an intestinal resection rate of 20.8-68% following enterostomy.[13-15] The high

has been done, the posterior wall is anastomosed complication rate in the present report may be due to

and the anterior walls exteriorised as a loop stoma. the fact that those enterostomies were created using

In one report of 91 patients including adults and intestine of tenuous viability, in patients with poor

children,[10] this method was effective. This method nutritional status and ongoing sepsis. However, 55% of

is thought to facilitate subsequent enterostomy these complications were related to the primary disease

closure by extraperitoneal approach. We have, and 45% directly related to the enterostomy procedure.

however, not used this technique in any of our

patients. Mortality has been reported with enterostomy done for

peritonitis from perforation or obstruction in infants

There are several challenges following enterostomy. and children. More number of deaths was reported

These challenges need to be carefully addressed to avoid in patients operated for peritonitis than for intestinal

serious complications and mortality: obstruction. Many factors influencing the deaths in

1. Fluid and electrolytes: This is important especially children are younger age, delayed presentation, longer

in small bowel stoma located high in the ileum interval between presentation and operation, sepsis,

or jejunum. Due to high output of effluent, much peritonitis, multi-organ failure.[3,7] The overall mortality

fluid and electrolytes can be lost and need to be in the present report was 46% but most were from the

meticulously replaced. Intravenous replacement primary disease condition and 8% directly related to

is critical until the intestine begins to adapt the enterostomy procedure, from hypokalaemia. Weber

and the stoma output reduces. Hypokalaemia is etal.,[15] evaluated enterostomies in newborns and found

common and potassium replacement should be an overall morbidity of 28.3%. They put emphasis on

318 October-December 2013 / Vol 10 / Issue 4 African Journal of Paediatric Surgery

Ameh, et al.: Peritonitis from acute intestinal disease in Children: Role of damage control enterostomy

the fact that early and late mortality is due to coexisting 2. Ameh EA. Intestine resection in children. East Afr Med J

2001;78:477-9.

diseases, prematurity, short-bowel syndrome, liver

3. Abdur-Rahman LO, Adeniran JO, Taiwo JO, Nasir AA, Odi T. Intestine

failure and sepsis and is not usually caused by a resection in Nigerian children. Afr J Paediatr Surg 2009;2:85-7.

complicated enterostomy course. In another report of 4. Singh M, Owen A, Gull S, Morabito A, Bianchi A. Surgery for

334 children (excluding neonates, atresias, anorectal intestinal perforation in preterm neonates: Anastomosis vs. stoma.

J Pediatr Surg 2006;41:725-9.

malformations, Hirschsprungs disease, trauma and

5. Nikhil T, Romesh L, Pathania OP. Pedicled ileal seromuscular flap.

tumours) with peritonitis, [16] 44 (13.2%) required A new technique for protection of intestinal anastomosis in patients

terminal ileostomy. Of 290 that did not have ileostomy, with peritonitis. Available from: http://www.jkscience.org/archive/

28 (9.7%) needed re-exploration for anastomotic leak, volume7/pedicled.pdf [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 23].

6. Moriura S, Nakahara R, Ichikawa T. A new Pedicled seromuscular

burst abdomen or faecal fistula, while three (6.8%) of the

flap technique for high risk intestinal anastomosis. Surg Today

ileostomy group needed to be re-explored. Mortality in 1997;27:379-81.

the ileostomy group was 1.8% compared to 8.4% in the 7. Uba AF, Chirdan LB, Ituen AM, Mohammed AM. Typhoid intestinal

group that did not have an ileostomy, and mortality from perforation in children: A continuing scourge in a developing

country. Pediatr Surg Int 2007;23:33-9.

stoma closure was 2.6% from convulsion. This report

8. Ameh EA. Typhoid ileal perforation in children, a scourge in

and our experience suggest that enterostomy is safe and developing countries. Ann Trop Paediatr 1999;19:267-72.

may improve outcome in children with peritonitis from 9. Ameh EA. The morbidity and mortality of right hemicolectomy

acute intestinal disease. for complicated intussusception in infants. Niger Postgrad Med J

2002;9:123-4.

10. Lange R, Dominquez Fernandez E, Friedrich J, Erhad J, Eigler FW.

CONCLUSION The anastomotic stoma: A useful procedure in emergency bowel

surgery. Langenbecks Arch Chir 1996;381:333-6.

Enterostomy as a damage control or salvage measure 11. Frileux P, Attal E, Sarkis R, Parc R. Anastomic dehiscence and severe

peritonitis. Infection 1999;27:67-70.

in very ill children with intestinal perforation and

12. Levy E, Palmer DL, Frileux P, Parc R, Huguet C, Loygue J. Inhibition

gangrene with severe peritonitis, oedematous intestine of upper gastrointestinal secretions by reinfusion of succus entericus

and whenever intestinal viability is in question is into distal small bowel. Ann Surg 1983;198:596-600.

useful in minimizing mortality and should be used 13. OConnor A, Sawin RS. High morbidity of enterostomy and its

closure in premature infants with necrotizing enterocolitis. Arch

where necessary. Careful attention to technical details Surg 1998;133:875-80.

at stoma creation and meticulous attention to fluid 14. Steinau G, Ruhl KM, Hornchen H, Schumpelick V. Enterostomy

and electrolyte balance and stoma care, especially in complications in infancy and childhood. Langenbecks Arch Surg

the first two weeks following surgery, are important 2001;386:346-9.

15. Weber TR, Tracy TF Jr, Silen ML, Powell MA. Enterostomy and its

in preventing morbidity and mortality. A randomized, closure in newborns. Arch Surg 1995;130:534-7.

controlled, comparison of damage control enterostomy 16. Ghritlaharey RK, Budhwani KS, Shrisvastava DK. Exploratory

with primary anastomosis would be needed but this laparatomy for acute intestinal conditions in children: A review of

may present ethical challenges. 10 years experience of 334 cases. Afr J Paediatr Surg 2011;8:6-69.

REFERENCES Cite this article as: Ameh EA, Ayeni MA, Kache SA, Mshelbwala PM. Role of

damage control enterostomy in management of children with peritonitis from

acute intestinal disease. Afr J Paediatr Surg 2013;10:315-9.

1. Ameh EA, Nmadu PT. Intestinal volvulus: Aetiology, morbidity,

Source of Support: Nil. Conflict of Interest: Nil.

and mortality inNigerianchildren. Pediatr Surg Int 2000;16:50-2.

African Journal of Paediatric Surgery October-December 2013 / Vol 10 / Issue 4 319

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without

permission.

You might also like

- Nurse Practitioner Sep 2000 25, 9 ProquestDocument8 pagesNurse Practitioner Sep 2000 25, 9 ProquestVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Nurse Practitioner Sep 2000 25, 9 ProquestDocument8 pagesNurse Practitioner Sep 2000 25, 9 ProquestVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Literature 3 PDFDocument1 pageLiterature 3 PDFVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Literature 3Document1 pageLiterature 3Vhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- GyygDocument10 pagesGyygVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Literature 5 MassageDocument7 pagesLiterature 5 MassageVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Escharotomy GuidelinesDocument2 pagesEscharotomy GuidelinesVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Literature 5 MassageDocument7 pagesLiterature 5 MassageVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Learning Zone: An Overview of Cardiovascular Disease Risk AssessmentDocument10 pagesLearning Zone: An Overview of Cardiovascular Disease Risk AssessmentVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- SYOKDocument5 pagesSYOKVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Keluarga 3Document13 pagesJurnal Keluarga 3Vhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- 191 755 1 PBDocument6 pages191 755 1 PBVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- C122Document14 pagesC122anugerahNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Keluarga 4Document10 pagesJurnal Keluarga 4Vhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Terapi Tertawa Terhadap Perubahan Tekanan Darah Pada Lansia Dengan Hipertensi Sistolik Terisolasi Di Panti Sosial Budi Agung KupangDocument11 pagesPengaruh Terapi Tertawa Terhadap Perubahan Tekanan Darah Pada Lansia Dengan Hipertensi Sistolik Terisolasi Di Panti Sosial Budi Agung KupangAndyk Strapilococus AureusNo ratings yet

- Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine Jan 2000 6, 1 ProquestDocument8 pagesAlternative Therapies in Health and Medicine Jan 2000 6, 1 ProquestVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Asymptomatic and Mild Primary Hyperparathyroidism: SciencedirectDocument8 pagesAsymptomatic and Mild Primary Hyperparathyroidism: SciencedirectVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Nurse Practitioner Sep 2000 25, 9 ProquestDocument8 pagesNurse Practitioner Sep 2000 25, 9 ProquestVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal TugasDocument9 pagesJurnal TugasVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- SYOKDocument5 pagesSYOKVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Kritisi Jurnal NCDocument11 pagesKritisi Jurnal NCVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Current Perspective GBS (Min Zhong, Fang-Cheng Cai)Document8 pagesCurrent Perspective GBS (Min Zhong, Fang-Cheng Cai)Lalalala Gabriella KristianiNo ratings yet

- Hipersensitivitas 3Document9 pagesHipersensitivitas 3Vhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Literature 5 MassageDocument7 pagesLiterature 5 MassageVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Manifestasi HisprungDocument7 pagesJurnal Manifestasi HisprungVhiena Shitta100% (1)

- OutDocument7 pagesOutDonJohnNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Advanced Life Support Update For The Emergency Physician - Review of 2010 Guideline ChangesDocument12 pagesPediatric Advanced Life Support Update For The Emergency Physician - Review of 2010 Guideline ChangesVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- ABC Preoperative Triage System in Breast AugmentationDocument7 pagesABC Preoperative Triage System in Breast AugmentationVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- Nurse Practitioner Sep 2000 25, 9 ProquestDocument8 pagesNurse Practitioner Sep 2000 25, 9 ProquestVhiena ShittaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Abdominal X RayDocument6 pagesAbdominal X RayJennyu YuNo ratings yet

- Filia D. Yaputri A34 Barium Enema IDocument3 pagesFilia D. Yaputri A34 Barium Enema ITatyannah Alexa MaristelaNo ratings yet

- Clark2016 Benign Anal DiseaseDocument7 pagesClark2016 Benign Anal DiseaseJohana Dellaneira Aucancela RamosNo ratings yet

- PancreatitisDocument7 pagesPancreatitisavigenNo ratings yet

- SEO-Optimized Title for Patient Visit RecordsDocument214 pagesSEO-Optimized Title for Patient Visit RecordsDewi PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Fecalysis: Verian John Hoo - Sudario College of Medical TechnologyDocument58 pagesFecalysis: Verian John Hoo - Sudario College of Medical Technologyepson printerNo ratings yet

- Kompetensi Bedah DigestifDocument5 pagesKompetensi Bedah DigestifOksayana Lutta100% (1)

- Intestinal Fluid and Electrolyte Movement Anatomy and PhysiologyDocument4 pagesIntestinal Fluid and Electrolyte Movement Anatomy and Physiology365 DaysNo ratings yet

- LEONCITO - Module 16 Worksheets 2Document12 pagesLEONCITO - Module 16 Worksheets 2Anton LeoncitoNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation (Age) NG Grp. A2 FinalDocument43 pagesCase Presentation (Age) NG Grp. A2 Finaljean therese83% (6)

- Constipation: Causes, Prevention Tips & Natural RemediesDocument2 pagesConstipation: Causes, Prevention Tips & Natural RemediesPrashant jainNo ratings yet

- Exam 1 Study GuideDocument3 pagesExam 1 Study GuideNataraj LoganathanNo ratings yet

- Colorectal Cancer PresentationDocument30 pagesColorectal Cancer PresentationfaikaNo ratings yet

- ACG and CAG Clinical GuidelineDocument2 pagesACG and CAG Clinical GuidelineNabila IsnainiNo ratings yet

- 20 Questions Abdominal PainDocument3 pages20 Questions Abdominal Painsumiti_kumarNo ratings yet

- Control of Gastric SecretionsDocument57 pagesControl of Gastric SecretionsPhysiology by Dr Raghuveer100% (1)

- Abdomen CAP Questions and AnswersDocument6 pagesAbdomen CAP Questions and AnswersRathnaNo ratings yet

- Fibrosis of The Liver - Liver and Gallbladder Disorders - MSD Manual Consumer VersionDocument2 pagesFibrosis of The Liver - Liver and Gallbladder Disorders - MSD Manual Consumer VersionAMIRA HELAYELNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Asupan Serat Makanan Dan Cairan Dengan Kejadian Konstipasi Fungsional Pada Remaja Di Sma Kesatrian 1 SemarangDocument10 pagesHubungan Asupan Serat Makanan Dan Cairan Dengan Kejadian Konstipasi Fungsional Pada Remaja Di Sma Kesatrian 1 SemarangHanifNo ratings yet

- PSGS Eligibility Form 2 - Tabulation of Cases 2024Document3 pagesPSGS Eligibility Form 2 - Tabulation of Cases 2024polkadatuinNo ratings yet

- CH 38 - Bowel EliminationDocument10 pagesCH 38 - Bowel EliminationJose GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever (Mhine)Document20 pagesTyphoid Fever (Mhine)Donna Salamanca DomingoNo ratings yet

- Gastritis and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Types, Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument23 pagesGastritis and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Types, Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentLisnawati Nur Farida100% (1)

- Hirschsprung Disease (Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon) : PathophysiologyDocument2 pagesHirschsprung Disease (Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon) : PathophysiologyDiane Mary S. Mamenta100% (1)

- Constipation in ChildrenDocument70 pagesConstipation in ChildrendrhananfathyNo ratings yet

- 26 Sri Rahayu OktavianiDocument123 pages26 Sri Rahayu OktavianiFebrianti FebriantiNo ratings yet

- DX Approach & MX of HMDocument8 pagesDX Approach & MX of HMjosephNo ratings yet

- Gastroenteritis HistoryDocument8 pagesGastroenteritis HistoryLeefre Mae D NermalNo ratings yet

- B. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disorder (GERD)Document15 pagesB. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disorder (GERD)Charisma MeromiNo ratings yet

- Jarvis Chapter 21 Study Guide 6th EditionDocument6 pagesJarvis Chapter 21 Study Guide 6th EditionlauramwoodyardNo ratings yet