Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Discover the Origins of Olmec Civilization in Mexico

Uploaded by

miguelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Discover the Origins of Olmec Civilization in Mexico

Uploaded by

miguelCopyright:

Available Formats

Maney Publishing

In the Land of Olmec Archaeology

In the Land of the Olmec by Michael D. Coe; Richard A. Diehl

Review by: Robert J. Sharer

Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Summer, 1982), pp. 253-267

Published by: Maney Publishing

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/529483 .

Accessed: 19/12/2013 20:12

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Maney Publishing is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Field

Archaeology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

In the Land of Olmec Archaeology

RobertJ. Sharer A Review Article

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Michael D. Coe and Richard A. Diehl, ln the Landof the Olmec, two vol-

umes plus maps. Volume I, TheArchaeologyof San LorenzoTenochtitlan,

416 pp.; Volume II, ThePeople of the River, 198 pp. The University of

Texas Press, Austin, Texas 1980. $100.00

Therecentpublicationof a comprehensivereportdescribingthe excavations

at San Lorenzo,Tabasco,Mexico, In the Land of the Olmec by MichaelD.

Coe and RichardA. Diehl, providesa significantcontributionto Mesoameri-

can archaeologyand a suitableopportunityto reviewthepresent statusof

Olmecstudies. The developmentof Olmecarchaeologyis a relativelyrecent

phenomenon,with the modernera of researchbeginningwithMatthewStir-

ling's surveysand excavationsat several sites in Mexico's Gulf Coast region

(1938-1946), and continuingwith the Universityof Californiaat Berkeley's

excavationsat the site of La Ventain the mid-1950s.The reportby Coe and

Diehl of the San Lorenzoinvestigations(1966-1968) adds considerablyto

our understandingof the origins and otheraspects of Olmeccivilization.

Thesecontributions,togetherwith several continuinggaps in our knowledge,

are reviewedby a resumeof Olmecchronology,archaeologicalremains,ex-

ternalconnections,and the implicationsof the Olmecfor the evolutionof

. . . . .

Mesoamerlcan clvlllzatlon.

Introduction certain until the pioneering surveys that resulted in the

Most archaeologistsand prehistoriansrecognize the discovery of Olmec sites and monuments in the dense

termOlmec as referringto the earliestknowncivilization rainforests of Tabasco and Veracruz were followed up

in Mesoamerica,centered in the tropical lowlands of by excavation. Today, after several decades of archae-

Mexico's Gulf coast (FIG. 1).1 But this recognitionhas ological research under extremely difficult conditions,

beenwon only recently,for a few decadesago Mesoam- these issues seem settled. The chronological question has

erican scholars were hotly debatingthe chronological been clarified by a series of consistent radiocarbondates.

placementof the Olmec, and questioningthe archaeo- The archaeological definition of Olmec civilization seems

logical validityof this prehistoricculture. secure, although many problems remain, at least in part

The questionswere askedbecauseOlmec culturewas because of the difficulties common to reconstructing any

firstdefinedfrom a distinctiveart style, basedprimarily prehistoric civilization from material remains alone.

on looted artifactsdevoid of context, and sculptured No historical sources exist to supplement or amplify

monumentswithoutclearevidenceof theirchronological our knowledge of the Olmec. As with the later city of

position. The definitionof Olmec civilizationwas un- Teotihuacan in the Basin of Mexico, or the far earlier

Harappancivilization of the Indus Valley, we are left to

1. For a general introduction to Olmec civilization see Ignacio Bernal,

The Olmec World, translated from the Spanish by Doris Heyden and

reconstruct the complexities of civilization without re-

FernandoHorcasitas (Berkeley 1969), and Michael D. Coe, America's course to written documents or records.

First Civilization (New York 1968). Based on current research and hypotheses, the Olmec

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

254 In theLandof OlmecArchaeologylSharer

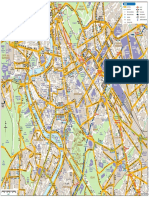

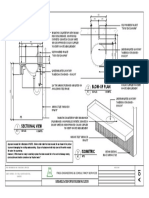

Figure 1. Map of the Olmec area.

represent the initial appearance of sufficient social com- theocratic and economic sources of power that directed

plexity to qualify as the first civilization in Mesoamerica. society, qualify the Olmec as a theocratic chiefdom3 or,

At its heart, this development was marked by the emer- perhaps more likely, an incipient theocratic state.4

gence of a small but powerful hereditary elite class pos- Much of the foregoing remains as hypothesis, for a

sessing considerable authority over a numerically larger great deal more archaeological research is necessary to

agriculturalpeasantry, as well as artisans, craftsmen, and test and refine our notions of Olmec civilization. How-

possibly other specialists such as merchants. Subsistence ever, the recent publication of In the Landof the Olmec

was based on the rich bounty of the Gulf coast, gained by Coe and Diehls is a watershed in Olmec studies, rep-

by harvesting plentiful aquatic resources, collecting, resenting the most thorough report of archaeological data

hunting, and investing in both extensive (slash-and-burn) from an Olmec site (San Lorenzo) that has to date ap-

and intensive (river-levee) agriculture. peared. Furthermore, the study incorporates an ethno-

The highest authorities in Olmec society seem to have graphic survey of the contemporary agriculturalists

been the rulers of several principal "dispersed cities,"2 dwelling in the San Lorenzo area that furnishes a unique

or major concentrations of ceremonial, economic, and ecological perspective for the reconstruction of ancient

political activity. The remains of these centers, such as life and social process in Olmec times. Although, like

San Lorenzo, La Venta, Tres Zapotes, and Laguna de any work of this magnitude, the San Lorenzo report has

los Cerros, indicate that they were constructed mostly of its weaknesses, most Mesoamerican archaeologists will

earthen platforms supporting perishable structures. The find it to be an indispensible addition to their libraries.

power of the rulers seems to have been based on super- The appearanceof Coe and Diehl's unprecedentedreport

natural sanctions and control of wealth by the redistri- is thus an appropriateoccasion to review the currentstatus

bution of local economic surpluses, such as foodstuffs of Olmec studies.

and exotic materials. The latter were imported at con-

siderable effort, and ranged from astounding quantities The Development of Olmec Archaeology

of basalt from the adjacent Tuxtla mountains, to smaller Portable Olmec objects have attractedthe attention of

amounts of obsidian and jadeite from highland areas as collectors for centuries. Small masks or celts of carved

far away as southern Guatemala. Many of these exotic

materials were shaped or carved, in a distinctive art style,

into symbols of the exalted status of the ruling elite and 3. William T. Sanders and Barbara J. Price, Mesoamerica. The Ev-

their supernaturalpatrons. Religious and political power olution of a Civilization (New York 1968) 115-134.

seem to have been fused in Olmec society, producing a 4. Paul Tolstoy "(Review of) Mesoamerica. The Evolution of a Civ-

form of theocratic authority. In general, therefore, the ilization," AmAnth 71 (1969) 554-558; Philip Drucker, ''On the Na-

control over human labor to the degree indicated by these ture of Olmec Polity,'' The Olmec and Their Neighbors, Essays in

building and trading activities, together with the inferred Memory of Matthew W. Stirling (hereafter OTN), E. P. Benson, ed.

(Washington, D .C . 198 1) 29-47 .

2. Bernal, op. cit. (in note 1) 49. 5. Michael D. Coe and Richard A. Diehl, In the Land of the Olmec.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 9, 1982 255

jadeite, bearingthe distinctive "baby face" or jaguar- Mexico City. Thus the choice of this term to refer to

like featuresof the Olmec style have been known since archaeological remains was a misnomer, unfortunate in

the SpanishConquest(e.g., a life-size jadeitemask, ap- that it caused some confusion between an historically

parentlytakento Italyin the 16thcenturyandnow in the known highland Mexican society and a far earlier and

collection of DumbartonOaks, and a miniaturemask unrelated prehistoric lowland civilization.

once belongingto the Royal House of Bavariaand now But for the first four decades of the 20th century the

in the ResidenzMuseumin Munich6).But althoughob- true age and significance of the ancient Olmec remained

jects such as these were prized as works of art, their unrecognized. The prevalent opinion was that these little-

sourceand culturalaffiliationremaineda mysteryuntil known sites along the Gulf coast represented an off-shoot

this century.The first reportof archaeologicalremains of Classic Maya civilization, which was better known

in the Gulf coast heartlandwas made in the mid-19th and more securely dated from monuments with hiero-

century,when Melgar y Serranopublishedan account glyphic calendrical dates that correlated to the 1st mil-

of the discoveryof MonumentA at the site of Tres Za- lennium A.C.l2 This cultural and chronological linkage

potes.7This monumentis a colossal basaltsculpturede- was to prove false, but given the lack of firm archaeo-

picting a human head of a kind now recognized as logical evidence, it seemed justified by the observation

characteristicof Olmec culture. that Olmec remains were located in a region adjacent and

Subsequentdecades saw furthercollecting and more similar to the environment of the Classic Maya.

publicationof Olmec-styleartifacts,althoughthe term The successful challenge to this thesis was founded in

Olmecwas not appliedto the emergingcorpusof objects evidence provided by archaeological research. Olmec

until the late 1920s.8 A few years before, Blom and archaeology came of age with the work of Matthew Stir-

LaFargepublishedtheir pioneering archaeologicalre- ling, who began his surveys and excavations in the Gulf

connaissanceof the Gulf coast and adjacentregions.9 coast region in 1938.l3 These investigations not only

This reportincludedan accountof the site of La Venta provided the first adequate information about already

anddescribeda series of newly discoveredmonuments. known sites, but led to the discovery of San Lorenzo,

One of the first attemptsto define the Olmec artstyle the site of the much later investigations reported by Coe

was madeby GeorgeVaillantin 1932.l0Vaillantsaw the and Diehl. 14

jaguar as a centraltheme in Olmec art, but confused Stirling conducted excavations in 1939 and 1940 at the

legitimateOlmec objectswith much lateritems such as site of Tres Zapotes, and in 1941 at Cerro de las Mesas,

gold artifacts.Partof the confusionmay have been be- a post-Olmec site where he discovered a famous cache

cause of the termOlmec ("Dweller in the Landof Rub- containing Olmec heirloom artifacts. In 1942 and 1943

ber'') itself.l l The originalreferencesto the Olmeccome Stirling excavated at La Venta, and finally, in 1945 and

from the SpanishConquestperiod, as the name of an 1946, at San Lorenzo.ls Although when he began his

ethnicgroupthen living in the Valley of Pueblaeast of career in Olmec archaeology Stirling thought he might

be probing part of Maya civilization,l6 his own research

and contacts with the outstanding art historian, Miguel

Covarrubias, soon convinced him otherwise.l7 Covar-

Vol. I: The Archaeology of San Lorenzo; Vol. II: The People of the

rubias and his fellow Mexican scholar, Alfonso Caso,

Wiver(Austin 1980).

held that the Olmec were far older than the Classic Maya,

6. Bernal, op. cit. (in note 1) 29. Summaries of Olmec research may old enough to be the Mesoamerican culturamadrefrom

be found in ibid. 28-32, and Matthew W. Stirling, ''Early History

of the Olmec Problem," Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec

(hereafterDOCO), E. P. Benson, ed. (Washington, D.C. 1968) 1-8.

7. Jose Maria Melgar y Serrano, i'Antiguedades Mexicanas," Socie-

12. Stirling,op. cit. (in note 6) 4-6.

dad Mexicana de Geografway Estadistica Boletzn 1 (1869) 292-297.

13. Ibid. A fascinatingaccountof Stirling'sresearchis providedby

8. Hermann Beyer, ''Bibliografica: Tribes and Temples," El Mexico

his wife andcolleague:MarionStirlingPugh, ''An IntimateView of

Antiguo 2 (1927) 305-313; Marshall H. Saville, "Votive Axes from

ArchaeologicalExploration," OTN ( 1981) 1-13 .

Ancient Mexico," Museum of the Americun Indian, Indian Notes 6

(1929) 266-299, 335-343. 14. Op. cit. (in note 5).

9. Franz Blom and Oliver LaF;arge,A Record of the Expedition to 15. Stirling,op. cit. (in note 6) 4-6.

Middle America Conducted by the Tulane University of Louisiana in

1925 (New Orleans 1926) .

16. MatthewW. Stirling, "Discovering the New World's Oldest

DatedWorkof Man," The National Geographic Magazine (hereafter

10. George C. Vaillant, ''A Pre-Columbian Jade,s' Natural History NGM) 76 (1939) 183-218.

32 (1932) 512-520, 556-558.

17. Michael D. Coe, "Matthew Williams Stirling, 1896-1975,"

11. Bernal, op. cit. (in note 1) 11. AmAnt41 (1976) 67-70.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

256 In theLandof OlmecArchaeologylSharer

which all othercivilizationsin this New Worldnuclear caches that yielded a consistent set of radiocarbondates,

areawere derived.18 placing occupation at La Venta in the Middle Preclassic

At Tres ZapotesStirlingdiscovereda brokenmonu- period of Mesoamerican prehistory (ca. 1100-500

ment,StelaC, with a partialcalendricalinscriptioncom- s.c.).26 As a result, La Venta was shown to significantly

posed of Mesoamerican bar-and-dot numerals pre-date Tres Zapotes Stela C, and the florescence of

representingthe date 16.6. 16. 18. Unfortunately,the cru- Olmec civilization was placed over a thousand years prior

cial initial numberwas missing, but based on the pre- to the Classic Maya. Although some scholars still be-

servedcoefficientsMarionStirlingcalculatedthe absent lieved that the Olmec were not this ancient,27 the issue

numberto havebeena 7. l9Thisreconstructed calendrical was resolved for most. The more recent excavations at

date correspondedto 31 B.C., according to the usually San Lorenzo by the Yale University team led by Michael

acceptedcorrelationto the Gregoriancalendarused for Coe have provided an independent set of radiocarbon

Maya inscriptions.This calculationmade Stela C over dates that indicate an even earlier position for Olmec

300 years older than the earliest Maya date then florescence. Furthermore, San Lorenzo yielded the first

accepted.20 evidence for the antecedents of Olmec civilization, dating

The battlelineswere thus drawnin the great Olmec to the early Preclassic era (ca. 1500-1150 s.c.).28 The

debate2l between scholarsled by Caso, Covarrubias, temporal placement of Olmec civilization is now consid-

and Stirling,22who held that the Olmec were far older ered secure, for it is consistent with independently de-

thanthe ClassicMaya, andthose who deniedthe Olmec rived chronologies from other Mesoamerican sites, and

chronologicalprimacy,led by most Mayaexperts.23The articulated by ceramic modes and other diagnostic

latterincludedJ. EricThompson,whose 1941paperpro- artifacts.29

vided the principalcounter-argument to Stirling's case

for the date of Stela C at Tres Zapotesand the antiquity A Contemporary View of the Olmec

of the Olmec.24 In order to assess the present status of Olmec studies,

The issuewas ultimatelysettledin favorof theprimacy several topics will be considered, beginning with cultural

of the Olmec by radiocarbonage assessmentsand the chronology, and continuing with a resume of archaeo-

articulationof Olmec artifactualsequences with well- logical remains (sculpture, artifacts, architecture, and

anchoredchronologies elsewhere in Mesoamerica.In sites), discussion of Olmec expansion beyond the heart-

1955 excavationswere renewedat La Venta by an ar- land, and concluding with the issue of the causes and

chaeologicalteam from the Universityof Californiaat consequences of Olmec civilization.

Berkeley.25This project recovered a series of carbon

samplesassociatedwith superimposedconstructionand Chronology

While the general outline of Olmec development is

18. Miguel Covarrubias, ''Origen y desarrollo del estilo artistico O1- well established30(TABLE1), there remains a somewhat

mec," Sociedad Mexicana de Antropologia, Reuniones de Mesa Re- frustrating lack of detailed artifactual sequences from

donda, Mayas y Olmecas (hereafter SMAMO) (1942) 46-49; idem, Olmec sites. The standby for such sequences in Me-

"La Venta: Colossal Heads and Jaguar Gods," DYN 6 (1944) 24-33;

Alfonso Caso, "Definicion y extension de complejo 'Olmeca',"

26. Philip Drucker and Robert F. Hiezer, ''Radiocarbon Dates from

SMAMO (1942) 43-46.

La Venta, Tabasco," Science 126 (1957) 72-73; Rainer Berger, John

19. Pugh, op. cit. (in note 13) 6. A. Graham, and Robert F. Heizer, ''A Reconsideration of the Age

of the La Venta Site,'' Contributions of the University of California

20. Stirling, op. cit. (in note 6). The upper portion of Stela C was

Archaeological Research Facility (hereafter UCARF) 3 (1967) 1-24.

discovered many years later, complete with the missing coefficient,

a seven, just as predicted; see Pugh, op. cit. (in note 13) 6. 27. William R. Coe and Robert Stuckenrath, Jr., "Review of La

Venta, Tabasco and Its Relevance to the Olmec Problem," The Kroe-

21. Bernal, op. cit. (in note 1) 31; Coe, op. cit. (in note 17) 69.

ber Anthropological Society Papers 31 (1964) 1-43.

22. Caso, op. cit. (in note 18); Covarrubias (1942), op. cit. (in note

28. Michael D. Coe, ''San Lorenzo and Olmec Civilization," DOCO

18); Stirling, op. cit. (in note 6). (1968) 41-78; ''The Archaeological Sequence at San Lorenzo Ten-

23. See, for instance, Sylvanus G. Morley, The Ancient Maya (Stan- ochtitlan, Veracruz, Mexico, " UCARF 8 (1970) 21 -34; Coe and

ford 1946) 40-42. Diehl, op. cit. (in note 5).

24. J. Eric Thompson, "Dating of Certain Inscriptions of Non-Maya 29. Paul Tolstoy, ''Recent Research into the Early Preclassic of the

Origin," Carnegie Institution of Washington, Theoretical Approaches CentralHighlands," UCARF 11 (1971); GarethW. Lowe, ''The Mixe-

to Problems (Cambridge 1941) . Zoque as Competing Neighbors of the Early Lowland Maya," The

Origins of Maya Civilization (hereafter OMC), R. E. W. Adams, ed.

25. Philip Drucker, Robert F. Heizer, and Robert J. Squier, Exca- (Albuquerque 1977) 197-248.

vations at La Venta, Tabasco, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin

(hereafter BAEBull) 170 (Washington, D. C . 1959) . 30. Bernal, op. cit. (in note 1) 106-117.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

.

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 9, 1982 257

Table 1. Summaryof Olmec chronology and culturaldevelopment(see note 42).

Mesoamericun Site sequences

(ulturalperlods Olmesperiodsandtrends Dates SanLorenzo LaVellta

- 1l00 A.C.

Postclassic - 900 A.C.

Villa Alta

Classic _ 200 A.C. (Hiatus)

Derived sculpturalstyles on Gulf coast

Late Preclassic and elsewhere (Izapanon Pacific coast) - 200 B.C. Remplas

111

Decline of Olmec civilization - 400 B.C. (Hiatus?)

Palagana

II 600 B.C.

IV

Middle Preclassic Expansionof Olmec beyond Gulf coast

(Olmec horizon in Mesoamerica) - (Hiatus) 11& 111

- 800 B.C. Nacaste

San Lorenzo

I _ | 000 B . C.

Initial florescence of Olmec A&B

civilization - '?

early PrecIass1c --------------------------------------- - 1200 B.C. Chicharras

Pre-Olmec

(Antecedentsto Olmec - 1400 B.C. Bajo

civilization) _ Ojochi

soamericais usuallypottery,but the preservationof ce- ological position of the various defined pottery types.34

ramicsis notoriouslypoor in the Gulf coast lowlands. Unfortunately, the San Lorenzo report does not provide

Thepotteryfromthe originalLa Ventaexcavations31 was us much in the way of quantitative data, so that readers

plaguedby this problem, as well as a lack of relevant cannot rework the chronological sequence. The seriation

comparativesequences at the time the studies were of ceramics from construction-fill contexts have been

done.32The analysis of the ceramicsfrom the later La used to produce accurate chronological sequences else-

Venta excavationshas yet to appear. The recent San where, 35 and it would be interesting to independently

Lorenzoreportbecomes all the more significantas a attemptthe same at San Lorenzo. Coe and Diehl provide

result,for it providesthe only detailedpotterysequence the raw sherd counts from one ''midden-like" deposit

(as well as descriptionsof artifacts)for an Olmec site.33 (StratigraphicPit II), together with a histogram that sup-

Problemsof preservationand context(a majorityof the ports and summarizes a portion of the available San Lor-

ceramicmaterialderivefrom secondaryor construction- enzo sequence.36 But a fuller presentation of the ceramic

fill deposits)have createduncertaintiesaboutthe chron-

34. Ibid. 133.

31. Drucker, Heizer, and Squier, op. cit. (in note 25).

35. Alfred V. Kidder, ';Archeological Investigations at Kaminaljuyu,

32. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 131-132. Guatemala," ProcPhilSoc 105 (1961) 559-570.

33. Ibid. 13 l -292. 36. Coe and Diehl, op cit. I (in note 5) fig. 97 and table 4-1.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

258 ln theLandof OlmecArchaeologylSharer

data seems to be called for, given the paucity of this kind period.42The chronological placement of Laguna de los

of information from the Olmec heartland. Regrettably, Cerros appearsapproximatelycontemporaneous with San

the earliest ceramic phase (Ojochi or ca. 1500-1350 B.C.) Lorenzo.43 But it is already apparent that there was a

defined at San Lorenzo is not representedin Stratigraphic long period of occvpation and cultural development in

Pit II (along with the Middle Preclassic Palangana and the Gulf coast heartland, during which individual centers

Late Preclassic Remplas materials, dated to ca. 600-400 of population and power rose and fell. The hallmarks of

and 300-100 B.C. respectively).37 The primary position Olmec civilization, especially monumental sculpture and

of the Ojochi phase is based on evidence from transported other "art", also underwent a long and complex devel-

fills revealed in the excavation of Monument 20, where opment.44Based on these factors, and on recognition of

Ojochi sherds, mixed with a "few Chicharras pieces" Olmec stylistic manifestations elsewhere in Mesoamer-

(dated as ca. 1250-1150 B.C.) were found to underliea ica, a reasonable consensus of Olmec chronology can be

stratumcontaining Bajio and San Lorenzo phase pottery presented (TABLE 1).

(dated as ca. 1350-1250 and 1150-900 B.C., respec-

tively).38 Thus, given the secondary context of the Mon- Archaeological Remains

ument 20 evidence, and accepting the sequence seen in The remains of Olmec culture include artifacts (port-

StratigraphicPit II (Bajio, Chicharras, San Lorenzo), it able items), monuments, architecture, and sites. By vir-

does not seem possible to determine the relative chron- tue of their merit, many of the artifacts and monuments

ological position of Ojochi from the presented excavated rank as great art. In fact, as mentioned earlier, Olmec

materials found at San Lorenzo. Rather, Ojochi is dated civilization was originally defined by its distinctive art

solely by its similarities to pottery from the Ocos phase style,45 and recognition of the Olmec horizon is still

defined far away on the Pacific coast of Guatemala.39 largely based on these characteristics.

This excursion into ceramic detail may give some idea The most familiar motif in Olmec art is the infantile

of the difficulties encountered in deriving a pottery se- human face with flared lips and down-turned mouth,

quence at San Lorenzo. rendered full front or in profile. When combined with

Comparingwhat is at present known about Olmec chro- feline characteristics, this is referred to as the werejag-

nology, it seems generally accepted that the two best uar, usually further marked by a cleft forehead.46 Other

known sites, San Lorenzo and La Venta, were not fully common motifs are human figures seated in a niche or

contemporaneous. The San Lorenzo report40concludes cave mouth, often depicted with earth-monsterjaws (as

that this center was occupied by agriculturalvillagers by entranceto the underworld), adults carrying or presenting

1500 B.C., and developed a fully florescent Olmec Period

infants (often as werejaguars), crocodilian or "dragon"

I culture (marked by monumental construction and the creatures, and tricephalicrepresentations.47The prevalent

sculpture of Olmec-style monuments) between 1150 and themes are both human (naturalistic) and supernatural

900 B.C. After 900 B.C. many of the San Lorenzo mon- (abstract). Joralemon has classified a series of deity rep-

uments appearto have been ritually disposed of (buried),

although occupation continued. The conclusions derived 42. Bernal, op . cit. (in note 1) 106- 117.

from La Venta see florescent Olmec occupation between

43. Frederick J. Bove, "Laguna de los Cerros: An Olmec Central

ca. 1000-500 B.C., without clear indications of a pre-

Place," Journalof New WorldArchaeology2:3 (1978) 1-56.

ceding developmental period as at San Lorenzo.41 Al-

though two colossal heads are known from Tres Zapotes, 44. Covarrubias, op. cit. (in note 18); Michael D. Coe, "The Olmec

Style and its Distribution,'' Handbookof MiddleAmericanIndians

the few clues from ceramics and the calendrical position (hereafter HMAI),R. Wauchope, ed. 3 (Austin 1965) 739-775.

of Stela C indicate that this site may, at least in part,

45. Ibid.

post-date Olmec occupation at both San Lorenzo and La

Venta, probably reaching its zenith in the Late Preclassic 46. Ibid.; also see Peter T. Furst, "The Olmec Were-Jaguar Motif

in Light of Ethnographic Reality," DOCO(1968) 143-178; ''Jaguar

Baby or Toad Mother: A New Look at an Old Problem in Olmec

Iconography," OTN( 1981) 149- 162.

47. David C. Grove, "Olmec Monuments: Mutilation as a Clue to

37. Ibid. 133. Meaning," OTN (1981) 49-68; Peter D. Joralemon, "The Olmec

Dragon: A Study in Pre-Columbian Iconography," Originsof Reli-

38. Ibid. 97.

giousArt&lconographyinPreclassicMesoamerica,H. B . Nicholson,

39. "Ojochi is a country cousin version of the far more sophisticated ed. (Los Angeles 1976) 27-71; Terry Stocker, Sarah Meltzoff, and

Ocos phase . . . and must be contemporary with it." Ibid. 137. Steve Armsey, "Crocodilians and Olmecs: Further Interpretationsin

40. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. (in note S) I:387, II:139-140. Formative Period Iconography," AmAnt 45 (19808 740-758; Jacinto

Quirarte, "Tricephalic Units in Olmec, Izapan-Style, and Maya Art,''

41. Berger, Graham, and Heizer, op. cit. (in note 26). OTN(1981) 289-308.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 9, 1982 259

resentations in Olmec art.48There is a sizable corpus of Maya civilization, although later mirrorswere often made

works on Olmec art, so that the present summary need in mosaics ratherthan the single pieces typical of Olmec

not cross into the domain of stylistic analysis.49 Rather, times .53

this paper will treat instead the archaeological signifi- Portable items such as these provide direct evidence

cance of Olmec remains, including those often considered of trading activity during the Olmec era, especially when

as art objects. The familiar problem with such objects sources of raw materials can be detected.54 In contrast,

is, of course, that most are plundered from their original the appearance of monumental Olmec sculpture outside

context, and thus have lost their significance for archae- of the heartlandis often considered prima facie evidence

ological purposes. Therefore, to avoid distortions pro- of short- or long-term Olmec occupation in foreign areas.

duced by looted remains, the following summary will In fact, the basis of defining the Gulf coast lowlands as

consider only those remains with secure proveniences. the heartland of Olmec civilization is that the greatest

concentration of monumental sculpture rendered in O1-

Sculpture mec style is found there.55 One distinctive Olmec form

Stone sculpture is surely the most prominent of Olmec of monumental sculpture seems restricted to this heart-

remains. Sculpture ranges from the truly monumental- land (colossal heads), while several others are rarely

including the carved basalt blocks transported from the found outside this region (flat-topped altars and human

Tuxtla mountains to the Gulf coast sites50 and the bas figures sculptured in the round). It should be noted at

reliefs rendered on the living rock faces at Chalcatzingo this point that the catalogue of the San Lorenzo monu-

in highland Mexico to easily transportablejadeite pen- ments presented by Coe and Diehl56 sets a new standard

dants, masks, and similar artifacts. in Olmec archaeology, especially because of the excellent

Many of the Olmec artifactsand sculptured motifs date illustrations by Felipe Davalos C.

to Period I and II and began traditions that can be traced The best known of Olmec monumental sculptures are

throughout the Precolumbian era right up to the Spanish the colossal heads,57 renderings of human heads carved

Conquest over 2000 years later. One of these distinctive in the round at a scale far larger than life. Fifteen ex-

artifacttraditionsthat began in the Olmec era was the use amples are known from three Olmec sites: La Venta with

of highly polished, concave ferric-ore mirrors.51These 4, San Lorenzo with 9, and Tres Zapotes with 2. The

items were traded into the Olmec heartland, either as largest known, San Lorenzo Monument 4, measures 2.85

blanks or finished products, from highland sources.52 m. high. Olmec colossal heads have been seen as rep-

They seem to have been importantsymbols of ideological resentations of ball-game players or warriors,58but the

and political power, worn about the neck of Olmec rulers,

as depicted on many monumental sculptures. This as-

sociation between ferric-ore mirrorsand theocratic power 53. JohnB. Carlson,"Olmec ConcaveIron-OreMirrors:The Aes-

seems to have continued in importanceduring subsequent thetics of a Lithic Technologyand the Lord of the Mirror,"OTN

(1981) 117-147.

54. As in the case of obsidianfrom San Lorenzo, identifiedfrom

48. Peter D. Joralemon, "A Study of Olmec Iconography," Dum- severalhighlandsources in Mexico and Guatemala;see RobertH.

barton Oaks Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology (hereafter, Cobean,MichaelD. Coe, EdwardA. Perry,Jr., KarlK. Turekian,

DOSPM) 7 (Washington, D .C . 1971) . andDinkarP. Kharkar,"ObsidianTradeat SanLorenzoTenochtitlan,

Mexico," Science 174 (1971) 666-671.

49. Covarrubias (1942), op. cit. (in note 18); Coe op. cit. (in note

44); Beatriz de la Fuente, "Toward a Conception of Monumental 55. Olmec monumentshave been classified variously;the 11 types

Olmec Art, " OTN (1981) 83-94; George Kubler, The Art and Ar- definedby WilliamC. Clewlow, Jr., "A StylisticandChronological

chitecture of Ancient America. The Mexican, Maya, and Andean Peo- Studyof OlmecMonumentalSculpture,"UCARF 19 (1974) areused

ples (Baltimore 1962); Tatiana Proskouriakoff, "Olmec and Maya Art; by Coe and Diehl. The presentationhere follows Grove, op. cit. (in

Problems of Their Stylistic Relation," DOCO (1968) 119-134; Mat- note 46) Table 1. RecentlyGrahamhas hypothesizedthatthe south

thew W. Stirling, "Monumental Sculpture of Southern Veracruz and coastof Guatemalawas the genesis areaof Olmecsculpture;see John

Tabasco," AIMAI3 (1965) 716-738; Charles R. Wicke, Olmec: An A. Graham,"Abaj Takalik:The Olmec style and its antecedentsin

Early Art Style of Precolumbian Mexico (Tucson 1971). PacificGuatemala,"Ancient Mesoamerica, J. A. Graham,ed. (Palo

Alto, California1981) 163- 176.

50. Howel Williams and Robert F. Heizer, "Sources of Rocks Used

in Olmec Monuments," UCARF 1 (1965) 1-39. 56. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 293-374.

51. Robert F. Heizer and Jonas E. Gullberg, "Concave Mirrors from 57. William C. Clewlow, Jr., Richard A. Cowan, James F.

the Site of La Venta, Tabasco: Their Occurrence, Mineralogy, Optical O'Connell,and Carlos Benemann,"Colossal Heads of the Olmec

Description, and Function, ' ' OTN ( 1981) 109- 116. Culture," UCARF 4 (1967).

52. Ibid. 110; Jane W. Pires-Ferreira, "Formative Mesoamerican 58. RomanPinaChanandLuisCovarrubias,"E1Pueblodel Jaguar,"

Exchange Networks with Special Reference to the Valley of Oaxaca," Consejo para la Planeacion e lnstalacion del Museo Nacional de

MMichMusAnth7 (Ann Arbor 1975). Antropologia (Mexico 1964). Citedin Grove,op. cit. (in note47) 61.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

260 In theLandof OlmecArchaeologylSharer

consensus seems to be that they are portraits of rulers.59 Finally, we may consider a series of bas relief sculp-

Michael Coe has noted that the headgear on each head tures, most of which appear to be carved upright stone

is unique, and this may have served to identify individual shafts (stelae), but a few fragmentarypieces may derive

rulers.60David Grove has pointed to one case, where the from other sources. This catagory includes two monu-

symbol of an eagle talon from the headgear of a colossal ments from San Lorenzo that appear to be among the

head (La Venta number 4) is also found on the headdress earliest Olmec sculptures found. Both (Monuments 41

of a figure carved in bas relief on San Lorenzo Monument and 42) are broken columnar stelae adorned with simple

14; if both represent the same person, as seems likely, reliefs of human figures.65 Some 24 stelae are known

this would be evidence of dynastic ties between these from the three sites of La Venta (17), San Lorenzo (5),

two Olmec centers.6' and Laguna de los Cerros (1). This category is the most

The term "altar" has been traditionally applied to ba- widespread of heartlandsculpturalforms, with numerous

salt blocks, usually with overhanging flat tops and sculp- examples known from outside the region, including Chal-

tured sides. Some 18 of these monuments are known catzingo,66San Miguel Amuco in western Mexico,67 and

from the three sites of La Venta (7), San Lorenzo (9, Padre Piedra in Chiapas (southem Mexico).68 The scenes

including 1 from nearby Potrero Nuevo), and Laguna de on Olmec stelae are often multi-figured and complex, but

los Cerros (2). A common altar motif is a human figure seem usually to include rulers. An imposing example of

seated in a niche, often holding an infant in the lap. This the latter appears to be represented on La Venta Stela 2,

has been interpretedas a representationof a ruler emerg- wearing an elaborate headdress and holding a scepter.

ing from the mouth of the underworld (the niche), sym- Stela 3 from the same site depicts a meeting between two

bolizing his supernaturalpower and right to rule.62 On personages, shown in profile. In both cases, the borders

La Venta Altar 4 the niched figure is connected by a cord of the bas reliefs contain smaller figures that may rep-

to other figures, which may symbolize kinship or descent resent attendants, ancestors, or supernaturalbeings.69

relationships.63 Most examples of these sculptures were broken or

The Olmec also carved a variety of figures in the round, mutilated in antiquity, a practice common in later Me-

including some 34 human effigies known from three sites: soamerican eras, as in the defacing of ruler portraits on

La Venta (16), San Lorenzo (11), and Laguna de los Maya stelae of the Classic period. The mutilation of

Cerros (7). In addition there are four smaller-than-co- Olmec monuments has been seen as the result of outside

lossal human heads at La Venta and one at San Lorenzo invasion or internal revolt.70 The available evidence,

that appear to be broken from full figures. These figures however, does not appear to support these suggestions.

are usually seen as portraits of rulers or deities. Animal Monumentmutilation seems established very early at San

figures were also carved in the round. Twelve of these Lorenzo, as indicated by broken fragments recovered

are known from La Venta, six at San Lorenzo (including from fill containing Chicharrasphase pottery. These frag-

1 each from nearby Tenochtitlan and Potrero Nuevo), ments included a piece apparently from a colossal head

and one from Laguna de los Cerros. The most common that would date earlier than ca. 1150 B.C. by this asso-

creature represented is feline (5 examples), but others ciation.71 The destruction of monuments seems to have

include monkeys (2), serpents (1), ducks (2), whales (1), occurred throughout the Olmec period, and continued

and arthropods(1). In addition, several full-figure mon- with the latest sculptures at Tres Zapotes.72 An analysis

uments depict two figures, as in the famous fragmentary

Potrero Nuevo Monument 3, which purportedly depicts 65. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 351-352.

a jaguar copulating with a human female, a theme Stirling 66. DavidC. Grove,"Chalcatzingo,Morelos,Mexico:A Reappraisal

proposed as representing the Olmec origin myth.64 of the OlmecRock Carvings,"AmAnt 33 (1971) 486-491.

67. David C. Grove and Louise I. Paradis,"An Olmec Stela from

San MiguelAmuco, Guerrero,"AmAnt 36 (1971) 95-102.

59. MatthewW. Stirling, "Stone Monumentsof the Rio Chiquito,

Veracruz,Mexico," BAEBull 157 ( 1955) 1-23; Michael D. Coe, 68. CarlosNavarrete,Archaeological Explorations in the Region of

''OlmecandMaya:A Studyin Realtionships,"OMEC (1977) 186. Frailesca, Chiapas, Mexico. Papers of the New WorldArchaeological

Foundation (hereafterNWAF) 7 (Orinda1960).

60. Coe, ibid.

69. Bernal,op. cit. (in note 1) pls. 17 and4, respectively.

61. Grove, op. cit. (in note 47) 66-67.

70. MatthewW. Stirling, "GreatStone Faces of the MexicanJun-

62. David C. Grove, "Olmec Altars and Myths," Archaeology 26 gle," NGM 78 (1940) 334; MichaelD. Coe, "Solvinga Monumental

(1973) 134-135. Mystery,"Discovery 3 (1967) 25.

63. Ibid. 134. 71. Coe andDiehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 294.

64. Stirling,op. cit. (in note59); Clewlow,op. cit. (in note54) 83-85 72. MatthewW. Stirling,"StoneMonumentsof SouthernMexico,"

challengesthis interpretation. BAEBull 138 (1943) 11.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 9, 1982 261

of the patterns of monument mutilation at Olmec sites thatthe Complex C mound never supported a structure,

undertakenby Grove indicates that the portraitsof rulers but represented an effigy volcano.80 Recently, Graham

received the brunt of destruction.73Depictions of rulers andJohnson have modified this hypothesis and presented

on altars, stelae, and full-figure portraits are nearly al- two other possible reconstructions of its original form.81

ways broken, decapitated, or defaced, and then buried. A magnetometersurvey has indicated that a concentration

The colossal heads seem to have warrantedspecial treat- of basalt or similar stone lies near its summit, possibly

ment less severe mutilation by grooving and conical a tomb chamber,82 but to date little is known of this

pitting,74and then burial ratherthan the more destructive importantconstruction, one of the largest for its time in

patternseen on the other monuments. This evidence sug- all of Mesoamerica, since it remains unexcavated.

gests periodic, ritualized activity. Grove proposes that The San Lorenzo map reveals the unusual form of this

these actions either marked the end of particular cal- site, situated on a low plateau apparently modified by

endrical cycles, or the termination of individual ruler's filling and leveling to form a series of six projecting

reigns (or changes in dynasties), perhaps to eliminate the ridges to the north, west, and south.83The mapped area

supernaturalpower believed to be embodied within the is approximately 1.2 km. x 0.8 km. Assuming that this

monuments prior to the installation of a successor.75 Per- area represents the extent of the artificial filling and lev-

haps both factors were responsible; individual acts of eling at San Lorenzo, the scale of labor involved must

destruction to mark the death of each ruler, and periodic have been colossal, implying a sophisticated organization

(calendrically determined) rites that saw the accumulated and sizable labor force. Coe has proposed that the form

defaced portraits of former rulers buried, as evidenced of San Lorenzo represents a gigantic, albeit unfinished,

by the alignment of interred monuments found at San effigy of a flying bird,84which while quite possible, only

LorenzO.76 proves that beauty (or bird effigies) lie in the eye of the

beholder.8s

Architecture and Sites The San Lorenzo map also reveals the existence of

Archaeological research in the Olmec heartland has "house mounds'', or remains of domestic occupation,

focused on the conspicuous remains at the core of major for the first time at an Olmec site. But unfortunately,

sites: the largest structures and monuments. Our infor- because only one of these mundane structureswas tested

mation about Olmec architectureremains essentially lim- by excavation, and then only sparsely treated in the San

ited to these kinds of remains at two sites: La Venta and Lorenzo report, Coe and Diehl's research makes little

San Lorenzo. And knowledge of overall site organization contribution to the beginning of Olmec settlement ar-

and settlement was practically nonexistent until the pub- chaeology.86 When compared to the contributions settle-

lication of the San Lorenzo report with its excellent site ment research has made to lowland Maya archaeology,87

maps.77 it is surprising that so little has been done towards this

The form and extent of La Venta remains somewhat potentially significant aspect of Olmec archaeology.

clouded, and there are discrepancies between the 1959 The findings from the excavation of the one house

map of the site core78 and a more recent version.79 The mound and the other structures at the site do raise a

controversy over the form and function of the largest

structureat La Venta, the Complex C Mound (some 30

m. high), illustrates this difficulty. Originally it was

80. Ibid.

mapped without removing obscuring vegetation, and de-

picted as a rectified rectangular pyramid. Later clearing 81. John A. Graham and Mark Johnson, "The Great Mound at La

Venta," UCARF 41 (1979) 1-5.

revealed it to be a fluted conical construction of earth,

and it was mapped accordingly; it was then suggested 82. Frank C. Morrison, William C. Clewlow, Jr., and Robert F.

Heizer, "Magnetometer Survey of the La Venta Pyramid, 1969,"

UCARF 8 ( 1970) 1-20.

73. Grove, op. cit. (in note 47) 62. 83. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 25-29 and map 2.

74. Clewlow, op. cit. (in note 55). 84. Ibid. 28, 387.

75. Grove, op. cit. (in note 47) 63-65. 85. In another publication, Diehl acknowledges an inability to per-

ceive this effigy form of San Lorenzo: Richard A. Diehl, "Olmec

76. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 298-299. Architecture: A Comparison of San Lorenzo and La Venta," OTN

77. Ibid. Map 2. (1981) 75.

78. Drucker, Heizer, and Squier, op. cit. (in note 25) fig 4. 86. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 20.

79. Robert F. Heizer, John A. Graham, and Lewis K. Napton, "The 87. See, e.g., Wendy Ashmore, ed., Lowland Maya Settlement Pat-

1968 Investigations at La Venta," UCARF 5 (1968) map. terns (Albuquerque 1981).

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

262 In theLandof OlmecArchaeologylSharer

questionas to the datingof occupationat San Lorenzo. La Venta made by Diehl9s reveals a surprising disparity

The distributionof potteryfromvery late (ca. 900-1100 between these best known of Olmec sites. In fact, given

A.C.) re-occupationthroughoutthe site88indicates the their architecturaldifferences, and apparent distinctions

possibilitythat many of these house moundsmay date in their ceramic traditions, the basic criteria for desig-

from that period, ratherthan the Olmec era. In fact, nating both San Lorenzo and La Venta as Olmec sites

althoughexcavationof the largerstructuresin the central rests on the similarities of their monumental sculpture

part of the site revealed evidence of underlyingfloor and the approximate contemporaneity of their occu-

constructiondatablefromthe periodof monumentcarv- pation.

ing (San Lorenzoto Nacastetimes, ca. 1150-700 B.C.), While both sites utilized local earthenmaterialfor most

the visible surfaceconstructionswere all datedeitherto construction, colored sands and clays being favored for

the Palangana(ca. 600-400 B.C.) or Villa Alta (ca. floors and platform surfaces respectively, the monumen-

900-1 100 A.C.) eras.89 The largestpyramidat San Lor- tal construction of the San Lorenzo site platform has no

enzo, MoundC3-1 (S m. high) was constructedduring known parallel at La Venta. Re-use of midden deposits

Villa Alta times.90 for fills appears much more common at San Lorenzo; in

This is not to say that the era of Olmec florescence fact, the rarity of occupational debris in construction at

(OlmecPeriodI) was devoid of large-scaleconstruction La Venta indicates the lack of substantial local popula-

activityat San Lorenzo.As mentionedpreviously,it ap- tions adjacent to the ceremonial precinct. Both sites pos-

pearsthatthe entiresite platformwas builtby filling and sess drains of basalt troughs, but the lagunas of San

leveling on a trulymonumentalscale priorto the place- Lorenzo may be unique. The general patternof rectilinear

ment of the colossal heads and other sculpturedmonu- structuralarrangementat La Venta existed at San Lorenzo

ments,probablyat the beginningof OlmecPeriodI. But by the Palangana phase, but as we have seen there is

thereis a somewhatmysteriouslack of structuresfrom little evidence of building platforms during the Olmec

this era at San Lorenzo, a fact Coe and Diehl account I period at the latter site. A variety of construction ma-

for by proposingthat the buildingsof Olmec PeriodI terials were used at La Venta that apparently were not

weredestroyedby lateractivity.9lTheonly directsupport used at San Lorenzo, including basalt columns and

forthishypothesiscomesfromone smallearthenplatform blocks, limestone slabs, and adobe blocks. The number

(MoundB2-1) thatexcavationrevealedwas builtduring and size of building platforms is far greater at La Venta,

the San Lorenzophase (ca. 1150-900 B.C.), locatedin culminating in the fluted conical Complex C mound. The

tte farNW corIlerof the site, whereit presumablyescaped size and number of ceremonial (dedicatory) deposits was

the postulateddestructionof latertimes.92 one of the most astounding features discovered in the

Otherthanthe monuments,the most conspicuousfea- excavations at La Venta. These consist of a wealth of

turesfrom Olmec PeriodI at San Lorenzoare a series caches containingjadeite and other artifacts, five massive

of 21 lagunas (reservoirs)andan extensivedrainthatran deposits of cut serpentine blocks found underlying con-

for at least 170 m. directlywest from between two of struction in Complex A, and five tombs found along the

these lagunas. The drain, built of trough-shapedbasalt N-S axis of the same area. Several small caches were

segmentswith flat basalt covers, was apparentlycon- excavated at San Lorenzo, but no evidence of massive

structedduringthe lastpartof the SanLorenzoor Nacaste offerings or tombs was discovered.

phases.93The lagunas may be derivedfromborrowpits, From this brief resume, it is obvious that the major

andseem to have been lined with clay. Theirpurposeis constructional energies at San Lorenzo were invested in

unknown,althoughCoe and Diehl suggest eitherutili- the mammoth site platform itself. At La Venta, the pri-

tarian water storage or ritual (purification-bathing) mary investment of wealth and labor went into massive

functions.94 offerings, tombs, large building platfox-llls,and at least

A comparisonof the architectureof San Lorenzoand one conical pyramid. Both sites must have used their

human resources to transport large amounts of earthen

fill from local sources as well as monolithic basalt blocks

88. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 213. from fartheraway that were carved to commemoratetheir

89. Ibid. 54-71. rulers.

90. Ibid. 50-54.

External Connections

91. Ibid. 388.

Beginningin Olmec PeriodI, and culminatingin Pe-

92. Ibid. 71-78.

riod II (the latter generally correspondingto the Me-

93. Ibid. 118-126.

94. Ibid. 30. 95. Diehl, op. cit. (in note 85) 69-81.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field Archaeology/Vol. 9, 1982 263

soamerican Middle Preclassic), the sphere of influence Olmec artifacts.98Similar pottery comes from the larger

for the Gulf coast centers ranged far beyond their hin- and wealthier site of Tlatilco, situated near the western

terland. The approximateboundaries of this exterIlalnet- exit of the basin, including forms decorated with motifs

work can be traced from the archaeological distribution emulating those found in the Olmec heartland.99These

of Olmec works artifacts from the heartland, or local- connections probably derive from trade contacts, al-

ized products that emulated Olmec works, as well as though some scholars have proposed that Olmec colonists

monumentalrock sculpture and cave paintings that testify may have resided at both Tlapacoya and Tlatilco to insure

to the presence of Olmec artisans, merchants, or even the continuity of economic ties with the Gulf coast

administratorsand priests far beyond the Gulf coast. centers. I00

In its widest extent, defined by the distribution of On the plateau south of the Basin of Mexico, two

tradedOlmec artifacts, this sphere of influence extended Olmec-related Early and Middle Preclassic sites occupy

from Central Mexico to Costa Rica in Central America, positions that suggest their function was to control routes

some 2500 km. to the SE. It is probablethat Olmec traders through the region. Las Bocas is situated in a defensible

were responsible for at least some of the far-flung dis- position at the eastern entry to the plateau, while Chal-

tribution of their masks, celts, and other objects. But it catzingo is located to the west, on the route leading to

is also likely that at least some of these items were traded the Rio Balsas valley and the corridorto westerIl Mexico.

beyond the limits of Olmec commerce because they were Las Bocas is badly plundered, but its burials seem to

highly esteemed and retained their value as heirlooms contain Olmec motif vessels.l°l Chalcatzingo is well

long after Olmec civilization waned.96 known for its outstanding Olmec-style bas reliefs carared

A more limited, but still extensive area within Me- on the volcanic deposits rising above the site. The ar-

soamerica can be defined for direct Olmec interaction. chaeological excavations conducted by Grove and his

The prime motive for this external involvement seems colleagues102have documented the origins of an Early

to have been economic the Olmec oversaw a wide- Preclas<,icvillage there, followed by expansion of the

spreadnetwork of tradeto provide the wealth and prestige settlement during the Middle Preclassic era when the bas

goods that helped support the exalted theocratic position reliefs seem to have been carved. In addition to these

of the Gulf coast rulers.97Accordingly, the source areas carvings, which probably made Chalcatzingo an impor-

of many of the prized exotic materials demanded by the tant focus for pilgrimages from throughout central Mex-

ruling elite correspondto regions with evidence of Olmec ico, Grove's research discovered several new bas reliefs

interaction. To the west of the heartland lies the central and a series of Olmec-style carved stelae, as well as a

Mexican highlands, a rich source of obsidian and other flat-topped altar built of a series of slabs. The excavation

volcanic minerals. To the sw is the Valley of Oaxaca, of high-status burials in stone-lined crypts revealed an

where workshops for the manufacture of ferric-ore mir- array of prestige goods, such as jadeite orIlaments, a

rors have been excavated. To the SE lies the fertile Pacific greenstone Olmec-style werejaguar figurine, and a fer-

coastal plain of modern Guatemala, the greatest Pre- ric-ore mirror. In one case, a crypt (Burial 3) contained

columbian source of cacao, and the route to the Maya a sculpturedhead broken from a statue, perhaps an effigy

highlands and their jadeite and obsidian, as well as the of the buried individual. Together, the archaeological

corridor to Central America beyond. A series of Middle evidence from Chalcatzingo suggests that it serarednot

Preclassic sites in these areas with evidence of Olmec only as a ceremonial center, but as a strategic trading

ties seem well situated to control access to local products station for highland products such as obsidian, ferric ores,

or protect and maintain the trade routes leading to the and possibly kaolin clay, controlled by an elite with

Gulf coast.

The dominant area within the central Mexican high-

98. PaulTolstoy,andLouiseI. Paradis,"EarlyandMiddlePreclassic

lands is the Basin of Mexico, where Mexico City is Culturein the Basin of Mexico," Science 167 (1970) 344-351.

presently located. By ca. 1200 B CU the villagers living

99. Ibid.

at Tlapacoya, set at the SE entrance to the basin on the

most logical route to the Gulf coast, were using pottery 100. Bernal,op. cit. (in note 1) 136-137; also see David C. Grove,

vessels and hollow figurines reminiscent of contemporary "The HighlandOlmec Manifestation:A Considerationof WhatIt Is

and Isn't," MesoamericanArchaeology:New Approaches,N. Ham-

mond,ed. (Austin 1974) 109-128, for a contraryinterpretation.

96. Anatole Pohorilenko, "The Olmec Style and Costa Rican Ar- 101. MichaelD. Coe, TheJaguar's Children(New York 1965).

chaeology, 99 OTN ( 1981 ) 309-327.

102. Grove,op. cit. (in note 47) 55-61; Grove,op. cit. (in note66);

97. Lee A. Parsons and Barbara J. Price, "Mesoamerican Trade and David C. Grove, KennethG. Hirth, David E. Buge, and Ann M.

Its Role in the Emergence of Civilization, " UCARF 11 ( 1971) Cyphers,"Settlementand CulturalDevelopmentat Chalcatzingo,"

169-195. Science 192 (1976) 1203- 1210.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

264 In theLandof OlmecArchaeologylSharer

strong Olmec ties, if not actually ruled by colonial Olmec also provided the naturalroute to CentralAmerica, avoid-

elites. This function has been typified by Hirth as a ing the rugged highlands inland, and the easiest access

"Gateway Community" . 103 to the obsidian andjadeite resources found in the souther

The westerIlmost evidence of Olmec presence in Mex- Maya highlands.1l0

ico is a carved stela from San Miguel Amuco in the Rio In coastal Chiapas, at the head of the Pacific plain,

Balsas drainage of Guerrero.l04Two cave sites, also in Navarrete's research has brought to light an array of

Guerrero (south of Chalcatzingo), furnish spectacular Olmec rock sculptures at Pijijiapan.111 Furtherdown the

polychrome paintings in Olmec style. One of these, at coast, recent excavations by Graham have revealed a

Oxtotitlan,105includes an elaborately adorIledfigure with series of Olmec-style monuments at Abaj Takalik, Gua-

an avian (eagle?) mask and costume, seated on a dais temala, in addition to the Olmec rock carving long known

decorated with a jaguar mask nearly identical to Gulf at this site.l12 Farthest to the SE iS Chalchuapa and the

coast motifs, such as that on La Venta Altar 4. Olmec-style carved boulder at Las Victorias.ll3 That the

The archaeological record from the other dominant Olmec also penetrated the Maya highlands is attested by

focus of highland civilization, the Valley of Oaxaca, the recent discovery of a fragmentaryOlmec-style carved

includes ceramic and other artifactual ties to the Gulf head at La Lagunita, in central Guatemala.1l4

coast Olmec during the Middle Preclassic. But like the While few of these Pacific coast Olmec sculptures can

Basin of Mexico, Oaxaca is devoid of direct sculptural be directly dated, stylistically they seem fully within the

links to Olmec art. It has been reasonably argued that in Middle Preclassic Olmec tradition (Period II). At Chal-

Oaxaca socio-cultural complexity developed only slightly chuapa, the pottery of this period includes specific Olmec

slower than on the Gulf coast. Accordingly, when the modes and motifs.1l5 A mammoth (20 m. high) conical

Olmec established trade contacts with the Oaxacan ruling earthenmound was also constructedat Chalchuapaduring

elites to secure desired goods, such as ferric-ore mirrors, this era, recalling a similar pyramid (the Complex C

they could not colonize or control this region. Rather Mound) at La Venta.1l6 It would appear that Olmec in-

exchanges were conducted between the Olmec and Oax- teraction had a catalytic effect on the cultural develop-

acan elites as equals in a trading relationship. 106 ment of the Preclassic societies along the Pacific plain,

The remaining major region of Olmec contact lay to for the growth of these societies continued at an accel-

the SE, along the rich Pacific coastal plain that stretches erated pace after the waning of Olmec connections in the

from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec into Central America. region.1l7 In the wake of the Olmec, the Pacific coastal

In later times this was the prime area for Mesoamerican plain was host to a rich sculptural tradition in the Late

cacao production. Cacao beans were prized both as a Preclassic, known as the Izapan style, and the earliest

food (and as a mild stimulant), and as a currency, used examples of Maya hieroglyphic texts and calendrical

by merchants throughout Mesoamerica.l07 Although notations.ll8 These appear to represent the direct ances-

highly perishable so that few archaeological traces re-

main, it is probable that Pacific coast cacao was one of

the mainstays of Olmec commerce. 108 One of the Olmec graph 36 (Philadelphia 1978) 175.

figures carved on the Las Victorias boulder at Chal- 110. Robert J. Sharer, "The Prehistory of the Southeastern Maya

chuapa, E1 Savador, cradles a rounded and ridged object Periphery," CA 15 (1974) 165- 187.

that appearsto represent a cacao pod. 109The Pacific plain 111. Carlos Navarrete, The Olmec Rock Carvings at Pijijiapan, Chia-

pas, Mexico, and Other Olmec Pieces from Chiapas and Guatemala,

NWAF Papers 35 (Provo 1974) .

103. Kenneth G. Hirth, "Interregional Trade and the Formation of

Prehistoric Gateway Communities,99 AmAnt 43 (1978) 35-45. 112. John A . Graham, ' 'Maya, Olmecs, and Izapans at Abaj Taka-

lik,9' XLII International Congress of Americanists, Actas 8 (1979)

104. Grove and Paradis, op. cit. (in note 67).

179-188.

105. David C. Grove, ''The Olmec Paintings of Oxtotitlan Cave,

113. Anderson, loc. cit. (in note 109).

Guerrero, Mexico," DOSPM 6 (Washington, D.C. 1970).

114. Alain Ichon, Les sculptures de la Lagunita, El Quiche, Guate-

106. Kent V. Flannery, "The Olmec and the Valley of Oaxaca: A

mala (Paris 1977) 34.

Model for Interregional Interaction in Formative Times,99 DOCO

(1968) 79-110. 115. Robert J. Sharer, "Pottery," in Sharer, ed., op. cit. III (in note

109) 124.

107. Rene Millon, 'iWhen Money Grew on Trees," unpublished

Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University (New York 1955). 116. Robert J. Sharer, ''Excavations in the E1 Trapiche Group,99in

Sharer, op. cit. I (in note 109) 73-74.

108. Parsons and Price, op. cit. (in note 97).

117. Sharer, op . cit. (in note 110) 170- 172.

109. Dana Anderson, "Monuments,9' in The Prehistory of Chal-

chuapa, El Salvador I, R. J. Sharer, ed., University Museum Mono- 118. Susanna W. Miles, ' ' Sculpture of the Guatemala-Chiapas High-

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 9, 1982 265

tors to the dynastic monuments that characterize lowland classic era of Olmec interaction124(see above), there is

Maya civilization during the subsequent Classic thus little to support the thesis that Olmec civilization

period.119 originated in westerIl Mexico, or anywhere else outside

of the Gulf coast.

Conclusion In the heartlanditself, the San Lorenzo reportprovides

From this all-too-brief summary it is apparent that some suggestive but inconclusive data on this issue. The

Olmec research to date has posed far more questions than San Lorenzo evidence, which is significant in attesting

answers. But this is a healthy and stimulating climate for the earliest occupation yet found at an Olmec site, sug-

further research which promises to provide exciting gests an in situ development from an initial village-level

results. foundation that seems to have been part of a general

The two major unresolved questions involve expla- tradition of settled communities adapted to the lowlands

nations for the origins of Olmec civilization, and the role of southern Mesoamerica.125

of the Olmec in the growth of later Mesoamerican civ- The various theories seeking to explain the rise of

ilizations. The San Lorenzo report addresses the first of civilization (or ''complex society") are well known, and

these problems,120but Coe and Diehl's research was not need not be reviewed here. In the case of the Olmec,

designed to cope with the second issue. these theories have provided fuel for several specific

Archaeology supports the idea that the heartland of developmental scenarios, based on the interrelated con-

Olmec cultural development lay in the tropical lowlands ditions of population growth, ecological diversity,

of the Gulf coast, and has chartedits chronological frame- competition, and differential access to scarce resources,

work. But the ultimate origins of Olmec civilization re- that resulted in the emergence of a ruling elite from an

main unresolved. 121 Are its roots to be found in the same egalitarian foundation. For example, William Rathje, in

tropical environment? Early works dealing with the 01- a model originally applied to the lowland Maya but that

mec, and their later tropical lowland companions, the he also saw as relevant to the Olmec, proposed that the

Maya, often assumed that this habitat was far too inhos- catalyst in this process was long distance trade.126 These

pitable uncomfortable, lacking in good agricultural exchange networks developed to supply scarce but nec-

land and other resources to have spawned civilization. essary goods such as salt, obsidian for cutting tools, and

Thus both the Olmec and the Maya were often seen as basalt for grinding stones, that were unavailable in the

an enigma, an exception to the ''rule" as to the origins tropical lowlands of Mesoamerica. In this scheme, the

of civilization. The only explanation lay in postulating Olmec elite would have grown out of the group of en-

that civilization had to be an import, transplanted into trepreneurswho organized and controlled trade to supply

the lowlands from highland regions, once assumed to these vital commodities.

have had a greater potential for supporting the growth In the San Lorenzo report, Coe and Diehl adapt this

of complex societies. 122Beginning with Covarrubias,the scenario, adding new variables provided by their ar-

idea has persisted that Olmec origins lay in the wester chaeological research, and reinforced by an analogy de-

highlands of Guerrero, Mexico.l23 Although recent ar- rived from their enthnographicstudy of the contemporary

chaeological investigations in Guerreroindicate an Early San Lorenzo region. 127As the report acknowledges, con-

Preclassic development of village life and a Middle Pre- textual limitations within the archaeological data preclude

quantitativeassessments (size and rates of growth) of the

ancient population at San Lorenzo, especially during the

critical pre-Olmec I period (ca. 1500-1150 B.C.) when

lands and Pacific Slopes and Associated Hieroglyphs, " HMAI 2 (1965) it is assumed that the transition between egalitarian and

237-277; Coe, op. cit. (in note 44); Jacinto Quirarte, ''Izapan-Style non-egalitarian social structureoccurred. But by assum-

Art: A Study of its Form and Meaning," DOSPM 10 (Washington,

D.C. 1973); Lee A. Parsons, ''Post-Olmec Stone Sculpture: The O1-

mec-Izapan Transition on the Southern Pacific Coast and Highlands,"

OTN (1981) 257-288. 124. Louise I . Paradis, ' ' Guerrero, and Olmec ' ' OTN ( 1981)

195-208; John S. Henderson, Atopula, Guerrero, and OlmecHorizons

119. Sylvanus G. Morley and George W. Brainerd;revised by Robert

in Mesoamerica, Yale University Publication in Anthropology 77 (New

J. Sharer, The Ancient Maya, 4th ed. (Stanford, in press) Chapter 3.

Haven 1979).

120. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. II (in note 5) 139-152.

125. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 137; Lowe, op. cit. (in note

121. Ibid. 139; Graham, op. cit. (in note 55). 29) 204-218.

122. See, for instance, Betty J. Meggers, ''Environmental Limitation 126. William L. Rathje, ''The Origin and Development of Classic

on the Development of Culture," AmAnth 56 (1954) 801-824. Maya Civilization," AmAnt 36 (1971) 275-285.

123. Covarrubias (1942), op. cit. (in note 18) . 127. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 139-152.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

266 In theLandof OlmecArchaeologylSharer

ing populationgrowthand consequentincreasingcom- on this question. The first of these, referred to as the

petitionfor resourcesduringthis interval,Coe andDiehl "highland school," sees a contemporarygrowth of socio-

posit the origins of the San Lorenzoelite from groups political complexity in the Basin of Mexico and the Val-

(probablylineages) that gained control over the prime ley of Oaxaca equivalent to the Olmec. In this view, the

local resource:the ca. one-fifthof the landscapecorre- laterdevelopment of urbanstates in Mesoamerica, a high-

spondingto the fertileriverlevee soils (21%of the land land phenomenon, owes little, if anything, to the Olmec,

todaywithinthe 77 sq. km. surroundingthe site). They being a direct descendant of the Preclassic highland tra-

note thatSan Lorenzois in an especiallyproductiveset- tition.l30 The second view, the "lowland school" sees

ting, possessing more river levee land than furtherup- the Olmec as the culturamadreof all subsequent cultural

stream, and a longer growing season (because of less development, not only in the lowlands (such as the Clas-

flooding) than areas downstream,so that its emerging sic period Maya), but the highlands as well.l3l As often

ruling elite would have had an advantageover other happens in such debates, it would appear that the truth

groupsin the region. This same fact may have tended may lie somewhere between these positions, and that

to circumscribethe San Lorenzopopulation,preventing lowland-highland interaction, of the kind hypothesized

emigrationand allowing the new elite to intensifytheir by Flannery for the Preclassic Valley of Oaxaca, affected

authority.To bolsterthis scenario,Coe and Diehl apply cultural development in both regions.l32

the resultsof their ethnographicstudy, specificallythe If we assume that the primary purpose of Olmec in-

rise to powerof caciques ("leaders") in the nearbyvil- teraction with other Mesoamerican societies was eco-

lage of Tenochtitlan.Caciques gain power within the nomic, which seems highly probable, the answer to this

essentiallyegalitariansystemof todayby workingharder problem may lie in considering what the Olmec offered

to earn extra money, which they invest in good river in return for the exotic goods demanded by their theo-

levee land and transportation facilities. In time these in- cratic rulers. Gordon Willey has noted that the funda-

vestmentspay off as the caciques acquirewealth, pres- mental contribution made by Olmec civilization was that

tige, and politicalpower. it provided the basis for integrating a diverse and rela-

The second and complementaryfactor in Coe and tively isolated series of agricultural societies throughout

Diehl's model for the originsof the San LorenzoOlmec Mesoamerica.l33 While the immediate mechanism for

is the adoptionof Rathje'sscheme:elite controlof the this integration appears to have been economic-the for-

trade networksthat supplied vital importedgoods.128 mation of a tightly controlled trade network this same

Finally, they arguethat Olmec ideology reinforcedthe network also communicated the Olmec ideological sys-

entireprocess, for the politicalpowerof the rulingelite tem throughout Mesoamerica. In simplest terms, there-

was notbasedonly on controlover subsistenceandtrade, fore, in exchange for exotic goods the Olmec provided

but the supernatural realmas well. Coe and Diehl admit knowledge concepts of a universal order and the myths,

they do not know how the rulersof San Lorenzocame deities, and rituals, that explained this order that was

to monopolizethe relationshipbetween society and the adopted by their trading partners, the newly emerging

supernatural, nor whichcame first:did the possessionof elites of highland Mexico and the Pacific coastal plain,

religious authorityfacilitatethe acquisitionof political for very practical political purposes. For by adopting the

andeconomicpower,or vice versa?l29Buttherearemany Olmec cosmology, these neighboring elites could better

other questionsthat could be asked of this model. For integrate and better administer their subjects. In this way

Coe andDiehl's reconstruction representsa detailedand a common underlying cosmological order emerged, and

plausible hypothesis derived from their San Lorenzo integratedMesoamerica with an ethos that prevailed until

study, but it is not an explanationof the origins of the the Spanish Conquest (vestiges of which survive to the

San Lorenzo Olmec. It will take considerablefurther present day).

effortto subjecteachof thecomponentsof thishypothesis The sculptured reliefs of Olmec personages found in

to archaeologicaltesting before we can even begin to highland Mexico and along the Pacific coastal plain are

considerthese scenariosas explanations. the most dramatic evidence of this common symbolic

The secondissue facing not only Olmec archaeology,

but all of Mesoamericanarchaeology,is the delineation

of the developmentalimpactmadeby Olmeccivilization 130. Sanders and Price, op. cit. (in note 3) 132-134.

on its neighbors.Two schoolsof thoughthavedeveloped 131. Caso, op. cit. (in note 18); Coe, op. cit. (in note 1); see also

Tolstoy, op. cit. (in note 4).

132. Flannery, op. cit. (in note 106).

128. Rathje, op. cit. (in note 126). 133. Gordon R. Willey, "The Early Great Styles and the Rise of the

129. Coe and Diehl, op. cit. I (in note 5) 148-149. Pre-Columbian Civilizations" AmAnth 64 (1962) 1-14.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 9, 1982 267

heritage.First adoptedand later adaptedin varyingde-

grees in local andregionalstyles to providethe focus of

ceremonial,economic,andpoliticallife, the Olmectheo-

cratic order transformedmuch of the rest of Meso-

america,ultimatelycontributingto the rise of states as

diverseas those of Teotihuacan,Oaxaca,and the Maya

lowlands.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thankProfessorsWendy A. Ashmore,Mi-

chael D. Coe, RichardA. Diehl, and David C. Grove

for their commentsand suggestionsthat aided the re-

finementof this paper.The author,however, takes full

responsibilityfor its content.

Theauthorfirst encounteredevidenceof Olmec

expansionbeyondthe Gulf coast lowlandsduring

excavationsin MiddlePreclassic contextsat

Chalchuapa,El Salvador(1966-1970), a research

programhe directedfor the UniversityMuseum,

Universityof Pennsylvania.Since then he has directed

the VerapazProject in the highlandsof Guatemala

(1971-1973), and the QuiriguaProject in the lowlands

of the MotaguaValleyin NE Guatemala(1974-1979),

for the UniversityMuseumwherehe is currently

AssociateCuratorof the AmericanSectionand

AssociateProfessorin the AnthropologyDepartmentof

the Universityof Pennsylvania.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Thu, 19 Dec 2013 20:12:23 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Amazing Places (Tell Me Why #128) (Gnv64)Document99 pagesAmazing Places (Tell Me Why #128) (Gnv64)hamed hatami100% (1)

- Turin PapyrusDocument5 pagesTurin PapyrusNabil Roufail100% (1)

- (Gale) Spanish-American WarDocument235 pages(Gale) Spanish-American WarmiguelNo ratings yet

- Andrews Iv Shells Yucatan PDFDocument140 pagesAndrews Iv Shells Yucatan PDFDixsis KenyaNo ratings yet

- The Origins of The Final Solution. The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy September 1939-March 1942. Comprehensive History of The Holocaust PDFDocument631 pagesThe Origins of The Final Solution. The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy September 1939-March 1942. Comprehensive History of The Holocaust PDFmiguelNo ratings yet

- A Greek Cave Sanctuary in Sphakia SW CreteDocument54 pagesA Greek Cave Sanctuary in Sphakia SW CreteJeronimo BareaNo ratings yet

- Rosicrucian Digest, January 1955Document44 pagesRosicrucian Digest, January 1955sauron385100% (1)

- Linda Schele (1942-1998): Pioneering Mayanist who revolutionized understanding of ancient MayaDocument3 pagesLinda Schele (1942-1998): Pioneering Mayanist who revolutionized understanding of ancient MayamiguelNo ratings yet