Professional Documents

Culture Documents

321

Uploaded by

Diego Guevara Valenzuela0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views2 pagesGeoff Eley's essay on the politics of globalization presents a powerful critique of current 'globalization talk' he argues for a more discriminating sense of the complex historical geographies of economy, society and politics. He also illuminates a veritable galaxy of ideas currently being debated by theorists across the academy.

Original Description:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentGeoff Eley's essay on the politics of globalization presents a powerful critique of current 'globalization talk' he argues for a more discriminating sense of the complex historical geographies of economy, society and politics. He also illuminates a veritable galaxy of ideas currently being debated by theorists across the academy.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views2 pages321

Uploaded by

Diego Guevara ValenzuelaGeoff Eley's essay on the politics of globalization presents a powerful critique of current 'globalization talk' he argues for a more discriminating sense of the complex historical geographies of economy, society and politics. He also illuminates a veritable galaxy of ideas currently being debated by theorists across the academy.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

FEATURE

Global Times and Spaces:

On Historicizing the Global

INTRODUCTION

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org at Pontificia Universidad Cat?lica de Chile on October 4, 2010

Geoff Eley’s essay on the politics of globalization, published in History

Workshop Journal 63, presents a powerful critique of current ‘globalization

talk’ amongst politicians, journalists, lobbyists and academics.1 In common

with many other critics, he argues for a more discriminating sense of

the complex historical geographies of economy, society and politics that

have characterized the long-term development of global capitalism, whose

unevenness tends to be flattened out in neo-liberal accounts of the process.

He also illuminates a veritable galaxy of ideas currently being debated

by theorists across the academy, as they grapple with some of the more

striking changes in the contemporary global political economy.

Globalization, as anthropologist James Ferguson puts it his account of

Africa’s place in the new world order, is a process ‘not of planetary

communion, but of disconnection, segmentation, and segregation – not a

seamless world without borders, but a patchwork of discontinuous

and hierarchically ranked spaces, whose edges are carefully delimited,

guarded and enforced’.2

In the face of what Geoff Eley describes as ‘the inescapable discursive

noise of globalization’, historians have begun to expose and explore the

historical depth and geographical differentiation of the world-economic

processes too often currently described as entirely new or entirely universal.

Seen in the light of his essay, however, this historicizing response is

necessary but not sufficient. The challenge posed by recent events on the

world stage – the end of the Cold War, the intensification of post-Fordism,

the consequences of 9/11, the reconfiguration of global power in the wake of

US intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan – is to reconsider the terms on

which these global histories are understood, and their effects in the world

today. In this context, Eley draws attention to an array of recent work which

re-centres, in various ways, the condition of slavery and servitude in the

narratives of global capitalism, and which questions the analytical

precedence conventionally given to waged work in the framework of

Marxist political economy. This inevitably requires a corresponding effort to

de-centre, geographically and historically speaking, the experience of

Western Europe in the era of Fordism.

Given the significance and scope of the issues raised by Geoff Eley’s

essay, History Workshop Journal invited contributions to a roundtable

debate from four leading historians working on economic, political and

History Workshop Journal Issue 64 doi:10.1093/hwj/dbm038

ß The Author 2007. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of History Workshop Journal, all rights reserved.

322 History Workshop Journal

cultural aspects of what has come to be known as world history. Of course,

thinking in world-historical terms is nothing new for historians – indeed,

in its Enlightenment form (only one of its many guises, as several

contributors point out), this was once supposed to define the difference

between philosophical history and mere antiquarianism. Moreover, the

notion of a turn to ‘the global’ in writing history has become something of a

commonplace in recent years. The question raised here is how to think

globally while not effacing the local; or rather, how to conceive the processes

Downloaded from hwj.oxfordjournals.org at Pontificia Universidad Cat?lica de Chile on October 4, 2010

through which the experience of world history have become intensely

differentiated under the sign of ‘globalization’. This requires, in part, a

willingness to rethink the geography of the world historical process - that

‘patchwork of discontinuous and hierarchically ranked spaces, whose edges

are carefully delimited, guarded and enforced’ which James Ferguson

describes. For this very reason, several of the contributors to this roundtable

respond to Geoff Eley’s challenge to ‘historicize the global’ by highlighting

what they regard as the blind-spots in his own map of global change.

The need to rethink the histories of Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas

in the light of the host of uneven exchanges between them is today

more urgent than it has ever been. The eloquence and passion of the

responses which follow suggest grounds for hope that historians are up

to the challenge.

Felix Driver

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1 Geoff Eley, ‘Historicizing the global, politicizing capital: giving the present a name’,

History Workshop Journal, 63, pp. 154–88.

2 James Ferguson, Global Shadows: Africa in the Neoliberal World Order, Durham NC,

2006, p. 14.

You might also like

- Leonardo Da Vinci Anatomical Drawings From The Royal Library Windsor CastleDocument170 pagesLeonardo Da Vinci Anatomical Drawings From The Royal Library Windsor CastleCristina Stoian100% (2)

- Liechtenstein Palaces in Vienna From The Age of The Baroque (Art Ebook)Document66 pagesLiechtenstein Palaces in Vienna From The Age of The Baroque (Art Ebook)Tommy ParkerNo ratings yet

- Resume NDocument2 pagesResume NDiego Guevara ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- 913995362Document3 pages913995362Diego Guevara ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- Cover: Giorgio Vasari and Assistants (16th Century), Battle of Lepanto, Fresco, Sala Regia, Vatican. © Photoscala, FlorenceDocument25 pagesCover: Giorgio Vasari and Assistants (16th Century), Battle of Lepanto, Fresco, Sala Regia, Vatican. © Photoscala, FlorenceDiego Guevara ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- ABS surveys rules guideDocument1 pageABS surveys rules guideJohnNo ratings yet

- Black Soldier Fly larvae reduce vegetable waste up to 74Document11 pagesBlack Soldier Fly larvae reduce vegetable waste up to 74Firman Nugraha100% (1)

- Rules of Origin and Full Cumulation in Regional Trade Agreements (RCEPsDocument16 pagesRules of Origin and Full Cumulation in Regional Trade Agreements (RCEPsLina AstutiNo ratings yet

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning's The Cry of the ChildrenDocument5 pagesElizabeth Barrett Browning's The Cry of the ChildrenShirley CarreiraNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Chemical Processing Equipment: Nicholas Cheremisinoff, PH.DDocument3 pagesHandbook of Chemical Processing Equipment: Nicholas Cheremisinoff, PH.DIrfan SaleemNo ratings yet

- The Historical and International Foundations of The Socialist Equality Party Sri LankaDocument50 pagesThe Historical and International Foundations of The Socialist Equality Party Sri LankaSanjaya Wilson JayasekeraNo ratings yet

- Downfall OF MobilinkDocument26 pagesDownfall OF Mobilinkfizza.azam100% (1)

- Unit 3 - Theory of Production - MicroDocument50 pagesUnit 3 - Theory of Production - Microraghunandana 12No ratings yet

- 10 Ways To Make Your Country SuccessfulDocument7 pages10 Ways To Make Your Country SuccessfulHassan BerryNo ratings yet

- CIS Bayad Center Franchise InformationDocument11 pagesCIS Bayad Center Franchise InformationJay PadamaNo ratings yet

- 120619ER63130633Document2 pages120619ER63130633Prakalp TechnologiesNo ratings yet

- Transit Oriented Development Policy Guidelines: Amended December 2005Document44 pagesTransit Oriented Development Policy Guidelines: Amended December 2005Hiam GaballahNo ratings yet

- 2022 Term 2 JC 2 H1 Economics SOW (Final) - Students'Document5 pages2022 Term 2 JC 2 H1 Economics SOW (Final) - Students'PROgamer GTNo ratings yet

- HersheyDocument9 pagesHersheyPew DUckNo ratings yet

- Business ModelsDocument3 pagesBusiness ModelsSteven KimNo ratings yet

- Pemboran 3Document74 pagesPemboran 3Gerald PrakasaNo ratings yet

- Israel's Development from Nationhood to PresentDocument21 pagesIsrael's Development from Nationhood to PresentAbiodun Ademuyiwa MicahNo ratings yet

- Indonesia HollySys Base-Installation. 11.03.2019Document3 pagesIndonesia HollySys Base-Installation. 11.03.2019Aerox neoNo ratings yet

- Syngenta Annual Report 2014 - 2015Document120 pagesSyngenta Annual Report 2014 - 2015Movin Menezes0% (1)

- Cost Accounting For Ultratech Cement LTD.Document10 pagesCost Accounting For Ultratech Cement LTD.ashjaisNo ratings yet

- MALAYSIA Port Schedules-20200603-053951Document29 pagesMALAYSIA Port Schedules-20200603-053951MRimauakaNo ratings yet

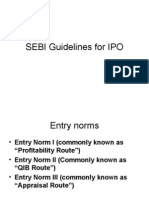

- SEBI IPO Guidelines SummaryDocument12 pagesSEBI IPO Guidelines SummaryAbhishek KhemkaNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need To Know About GST Goods and Services TaxDocument2 pagesEverything You Need To Know About GST Goods and Services TaxNagendra SinghNo ratings yet

- 14C 2RS HB 4631 Recommissioning Bataan Nuclear Power PlantDocument17 pages14C 2RS HB 4631 Recommissioning Bataan Nuclear Power PlantIan Martinez100% (4)

- Statsmls April2012Document2 pagesStatsmls April2012Allison LampertNo ratings yet

- Cafe Industry PresentationDocument10 pagesCafe Industry PresentationSandeep MishraNo ratings yet

- GlobalDocument373 pagesGlobalMiguel RuizNo ratings yet

- Full Download Work Industry and Canadian Society 7th Edition Krahn Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Work Industry and Canadian Society 7th Edition Krahn Test Bankdarienshadidukus100% (15)

- Ernesto Serote's Schema On Planning ProcessDocument9 pagesErnesto Serote's Schema On Planning ProcessPatNo ratings yet

- Perth Freight Link FOI DocumentsDocument341 pagesPerth Freight Link FOI DocumentsYarra Campaign for Action on Transport (YCAT)No ratings yet