Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Great Cas - Judicially Noticed Matters Can Support A Demurrer To A Complaint That Isvalid On Its Face

Uploaded by

tonyformsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Great Cas - Judicially Noticed Matters Can Support A Demurrer To A Complaint That Isvalid On Its Face

Uploaded by

tonyformsCopyright:

Available Formats

two documents in the record: (1) an Interspousal Transfer Deed recorded on February 14,

2002 whereby "William hereby agrees and consents to transmute 280 Kuss Road,

Danville, California, fiom community property to Debra's sole and separate property"

effective upon the signing of the "Transmutation Agreement" on February 14,2002; and

(2) the 2007 deed of trust on that property lists Ms. McCann, "an unmarried woman," as

the sole borrower on the 2007 deed of trust on the Danville property. Respondents

requested judicial notice of both of these documents, a request appellant did not oppose

and the court granted. (See West v. J. P. Morgan Chase Bank, N.A. (20 13) 2 14

Cal.App.4th 780, 802-803; Ragland v. U.S.Bank National Assn. (20 12) 209 Cal.App.4th

182, 194; Maryland Casualty Co. v. Reeder (1990) 22 1 Cal.App.3d 96 1,977; see also

Evid. Code, §$452,453.)

Finally, the law is clear that judicially-noticed matters are relevant in considering a

demurrer. In Del E. Webb Corp. v. Structural Materials Co. (1981) 123 Cal.App.3d 593,

604, the court held: "As a general rule in testing a pleading against a demurrer the facts

alleged in the pleading are deemed to be true, however improbable they may be.

[Citation.] The courts, however, will not close their eyes to situations where a complaint

contains allegations of fact inconsistent with attached documents, or allegations contrary

to facts which are judicially noticed. [Citations.] Thus, a pleading valid on its face may

nevertheless be subject to demurrer when matters judicially noticed by the court render

the complaint meritless." (See also City of Chula Vista v. County ofSan Diego (1994) 23

Cal.App.4th 1713, 1719.) This principle applies here, as the judicially-noticed records

clearly established that appellant had no interest in the Danville property.

In his sole brief to us,2 appellant contends that (1) he adequately pled a quiet title

cause of action, (2) if not, he should be allowed to amend it, and (3) the trial court was

Appellant filed no reply brief. Additionally, in his brief to us appellant cites to

the record in an entirely different appeal, i.e., Ms. McCann's appeal fiom the trial court's

judgment dismissing all of her causes of action, save one, in the FAC, and permitting her

to amend that one cause of action. Appellant assumes that the clerk's transcripts in the

two appeals are the same, but they are not. Similarly, this appeal does not involve, as

appellant assumes, any "appendices." Thus, appellant's citations to the record in his sole

wrong in finding his sole cause of action, i.e., the 10th cause of action for Quiet Title of

the FAC, was dependent on the validity of Ms. McCann's pleadings.

None of these contentions addresses the key issue asserted by the trial court as the

principal basis for its decision sustaining of the demurrer as to appellant's sole cause of

action, i.e., for quiet title. That basis was, as noted above, that pursuant to Code of Civil

Procedure section 76 1.020, subdivision (b), appellant was required, but failed to, assert

"that he in fact does have any 'title' to the subject property, much less 'the basis of the

title.' "

In his brief to us, and in support of his first contention, i.e., that he properly pled

an action to quiet title, appellant argues that (a) he "does not have to plead . . .

possession" and (b) he in fact alleged in the FAC that he had an " 'undivided 1/10

ownership interest in the property.' " However, neither of these arguments is of any

consequence. We agree that appellant did not have to plead ''possession;" indeed, neither

respondents nor the trial court suggested at any point that such was an issue. The fact

that he pled that he had a one-tenth ownership of the property is of no consequence in

view of the substantial record before us-a record not addressed in the slightest by

appellant-that, per documents of which both we and the trial court may take judicial

notice, he had in fact long since divested himself of any interest in the Danville property.

That fact also answers appellant's second contention, i.e., that he should be

allowed leave to amend the FAC. First of all, per the documents submitted by

respondents to the trial court, no amendment that appellant could submit could cure the

result dictated by the judicially-noticed documents regarding title to the Danville

property. Second, the grant or denial of a motion to amend is reviewed for abuse of

discretion. (See, e.g., Montclair Parkowners Assn. v. City of Montclair ( 1 999) 76

- -

brief to us are (except for a few to the reporter's transcript) of no value. However, the

record does include several important documents omitted from the clerk's transcript, but

before us via a motion to augment filed by respondents on January 6,20 14, and granted

by this court on February 10,20 14.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Sharpulator: List ThreeDocument3 pagesThe Sharpulator: List ThreeTim RichardsonNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Economics Sba UnemploymentDocument24 pagesEconomics Sba UnemploymentAndreu Lloyd67% (21)

- Great Case - A Malicious Prosecution Action Can Be Based On Administrative ProceedingsDocument16 pagesGreat Case - A Malicious Prosecution Action Can Be Based On Administrative ProceedingstonyformsNo ratings yet

- The Marriott WayDocument4 pagesThe Marriott WayDevesh RathoreNo ratings yet

- Arballo v. Orona-Hardee, Ariz. Ct. App. (2015)Document6 pagesArballo v. Orona-Hardee, Ariz. Ct. App. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Court Can Take Judicial Notice of Recorded DeedsDocument7 pagesGreat Case - Court Can Take Judicial Notice of Recorded DeedstonyformsNo ratings yet

- Insular Life Assurance Co. CBA DisputeDocument2 pagesInsular Life Assurance Co. CBA Disputedoraemon0% (1)

- Effects of Mother Tongue Based Multi-LinDocument7 pagesEffects of Mother Tongue Based Multi-LinAriel Visperas VeloriaNo ratings yet

- Great Case - A Final Judgment Is Binding Even If It Was Wrongly DecidedDocument9 pagesGreat Case - A Final Judgment Is Binding Even If It Was Wrongly DecidedtonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Mootness Explored in Great DetailDocument13 pagesGreat Case - Mootness Explored in Great DetailtonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Burden of Proof To Renew A Civil Harassment TRO or Restraining OrderDocument20 pagesGreat Case - Burden of Proof To Renew A Civil Harassment TRO or Restraining OrdertonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - A Case That Becomes Moot While An Appeal Is Pending Should Be DismissedDocument10 pagesGreat Case - A Case That Becomes Moot While An Appeal Is Pending Should Be DismissedtonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartyDocument36 pagesGreat Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartytonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - (Terry Childs, CCSF Computer Guru Employee Committed Crimes)Document74 pagesGreat Case - (Terry Childs, CCSF Computer Guru Employee Committed Crimes)tonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - A Contention Is Waived Unless There Is Analysis and Argument Supporting ItDocument10 pagesGreat Case - A Contention Is Waived Unless There Is Analysis and Argument Supporting IttonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - 373 Year Sentence To Criminal Defendant For Multiple Rapes and AssaultsDocument45 pagesGreat Case - 373 Year Sentence To Criminal Defendant For Multiple Rapes and AssaultstonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartyDocument36 pagesGreat Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartytonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartyDocument36 pagesGreat Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartytonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartyDocument36 pagesGreat Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartytonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartyDocument36 pagesGreat Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartytonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartyDocument36 pagesGreat Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartytonyformsNo ratings yet

- Cadlo v. Owens-ILlinois (2004) - Actual Reliance An Element of FraudDocument9 pagesCadlo v. Owens-ILlinois (2004) - Actual Reliance An Element of FraudtonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - A Statute Has Retrospective Effect When It Substantially Changes The Legal Consequences of Past EventsDocument9 pagesGreat Case - A Statute Has Retrospective Effect When It Substantially Changes The Legal Consequences of Past EventstonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartyDocument36 pagesGreat Case - An Unverified Complaint Is An Admission by The PartytonyformsNo ratings yet

- Graton Casino Elder Abuse Case - #A147100Document7 pagesGraton Casino Elder Abuse Case - #A147100tonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Textbook Case of Harassment Between NeighborsDocument10 pagesGreat Case - Textbook Case of Harassment Between NeighborstonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Assumption of The Risk Re Hack Squat MachineDocument8 pagesGreat Case - Assumption of The Risk Re Hack Squat MachinetonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Attorney Disqualified Due To Being A Percipient WitnessDocument6 pagesGreat Case - Attorney Disqualified Due To Being A Percipient WitnesstonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Statutory Causes of Action Must Be Pleaded With Specificity, Just Like FraudDocument31 pagesGreat Case - Statutory Causes of Action Must Be Pleaded With Specificity, Just Like FraudtonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Definition of What A Trial IsDocument6 pagesGreat Case - Definition of What A Trial IstonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - No Premises Liability When Guest Threw Bullet I BonfireDocument9 pagesGreat Case - No Premises Liability When Guest Threw Bullet I BonfiretonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Payee of Check Cannot Sue For Conversion If He Never Took Delivery of ItDocument12 pagesGreat Case - Payee of Check Cannot Sue For Conversion If He Never Took Delivery of IttonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Definition of What A Trial IsDocument6 pagesGreat Case - Definition of What A Trial IstonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - Buyer of Public Nuisance Liable For Prior Fines, On Demurrer The Facts in Exhibits Outweigh The Facts PleadedDocument10 pagesGreat Case - Buyer of Public Nuisance Liable For Prior Fines, On Demurrer The Facts in Exhibits Outweigh The Facts PleadedtonyformsNo ratings yet

- Great Case - How Wrongful Death Actions WorkDocument7 pagesGreat Case - How Wrongful Death Actions WorktonyformsNo ratings yet

- Lifeline Australia Director - Letter of Appointment.Document5 pagesLifeline Australia Director - Letter of Appointment.Kapil Dhanraj PatilNo ratings yet

- The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) Play BookDocument2 pagesThe Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) Play Bookterese akpemNo ratings yet

- 2018 Utah Voter Information PamphletDocument140 pages2018 Utah Voter Information PamphletOmer ErgeanNo ratings yet

- MPU 2163 - ExerciseDocument7 pagesMPU 2163 - ExerciseReen Zaza ZareenNo ratings yet

- Republic of Kosovo - Facts and FiguresDocument100 pagesRepublic of Kosovo - Facts and FiguresTahirNo ratings yet

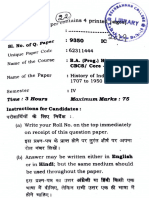

- B.A (Prog) History 4th Semester 2019Document22 pagesB.A (Prog) History 4th Semester 2019lakshyadeep2232004No ratings yet

- Conclusion To A Research Paper About The HolocaustDocument5 pagesConclusion To A Research Paper About The HolocaustgudzdfbkfNo ratings yet

- ESTABLISHING A NATION: THE RISE OF THE NATION-STATEDocument10 pagesESTABLISHING A NATION: THE RISE OF THE NATION-STATEclaire yowsNo ratings yet

- Quilt of A Country Worksheet-QuestionsDocument2 pagesQuilt of A Country Worksheet-QuestionsPanther / بانثرNo ratings yet

- Grand Forks BallotDocument3 pagesGrand Forks BallotinforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Transformation of Tribes in India Terms of DiscourseDocument7 pagesTransformation of Tribes in India Terms of DiscourseJYOTI JYOTINo ratings yet

- Women: Changemakers of New India New Challenges, New MeasuresDocument39 pagesWomen: Changemakers of New India New Challenges, New MeasuresMohaideen SubaireNo ratings yet

- Jerome PPT Revamp MabiniDocument48 pagesJerome PPT Revamp Mabinijeromealteche07No ratings yet

- Basics of Custom DutyDocument3 pagesBasics of Custom DutyKeshav JhaNo ratings yet

- Kulekhani Hydropower Conflict ResolutionDocument3 pagesKulekhani Hydropower Conflict ResolutionKisna Bhurtel0% (1)

- Penguin Readers Factsheets: by Jane RollasonDocument4 pagesPenguin Readers Factsheets: by Jane RollasonOleg MuhendisNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Contract LawDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Contract LawTsholofeloNo ratings yet

- Rizal's works promote nationalism and patriotismDocument5 pagesRizal's works promote nationalism and patriotismEleanor RamosNo ratings yet

- Jahan RamazaniDocument5 pagesJahan RamazaniMustafa A. Al-HameedawiNo ratings yet

- Sutan Sjahrir and The Failure of Indonesian SocialismDocument23 pagesSutan Sjahrir and The Failure of Indonesian SocialismGEMSOS_ID100% (2)

- 18 Barreto-Gonzales v. Gonzales, 58 Phil. 67, March 7, 1933Document5 pages18 Barreto-Gonzales v. Gonzales, 58 Phil. 67, March 7, 1933randelrocks2No ratings yet

- Mil Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesMil Reflection PaperCamelo Plaza PalingNo ratings yet

- FC - FVDocument88 pagesFC - FVandrea higueraNo ratings yet

- Buffalo Bills Letter 4.1.22Document2 pagesBuffalo Bills Letter 4.1.22Capitol PressroomNo ratings yet