Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kelly Angle

Uploaded by

raviinterCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kelly Angle

Uploaded by

raviinterCopyright:

Available Formats

Stocks & Commodities V17:12 (529-532): Markets Don’t Trend, They Burst by K.D.

Angle

TRADING TECHNIQUES

Markets THE BURST EFFECT

First, I looked at a 10-year history of the current bull stock

market and determined how many trading days generated

Don’t Trend,

most of the vertical price movement each year. My research

confirmed that 80% of the gains made in the stock market

have been generated in about three trading days on average

per calendar year. Unlike many other markets, however, the

They Burst stock market has been pretty much a straightforward affair

for many years.

Most other markets such as Treasury bonds, crude oil, and

foreign currencies have not experienced a decade-long bull

market the way the stock market has. In most other markets,

sometimes the trend is up, and sometimes the trend is down.

Is there really such a thing as a trend? Maybe not. Maybe a So rather than using a 10-year period in evaluating those

relatively few pops in price make up most of the market markets that do not concern stocks, I looked at each market

movement we see. and defined the direction of the trend in terms of calendar-

year periods.

by K.D. Angle Defining trends in terms of a calendar year gave me the

oes this statement, or something ability to compare differing markets and compare them with

like it, sound familiar? “Of the a major stock index such as the Standard & Poor’s 500. Doing

annual returns from the stock this helped me determine if this burst phenomenon was

D market over the last 10 years,

90% were generated in a month

or so, and unless you’re always

in the market, you’ll miss out

on those few days that generate

unique to the stock market or one that also occurred in other

markets, whether prices moved up or down. I used as ex-

amples four very different markets representing stocks (the

Standard & Poor’s 500), debt (T-bonds), currencies (yen),

and commodities (coffee).

the vast majority of returns.” I examined calendar years starting in 1983 and ending in

Variations of that statement 1998. In each calendar year, I determined that a market had

are common, and it’s true that an up year or a down year if the year-end closing price was up

an “always in the market” strategy has worked for portfolio or down relative to the closing price at the beginning of that

managers like Warren Buffett as well as large commodity/ year. If the year was up, I determined how many net up days

futures money managers that utilize long-term trend-follow- actually contributed to the highest closing price for that year.

ing strategies. Stepping back and taking a look at a 10-year I define a net up day as one that produced a high that was

chart of the daily prices of the Dow Jones Industrial Average higher than the previous highest high made up to that point

(DJIA) would certainly give an observer the impression that during that calendar year.

this has been a long-term trending bull market. Even if you

New Net up

examined a monthly chart over the last few decades, you high days

would come up with a similar conclusion. But if you were to

analyze the movement of daily net vertical price movement,

you would begin to understand that there was something

altogether different taking place. New

As a market timer, I wanted to know if market prices really high

tended to move in bursts, something that generally favors the

“in the market all the time” approach. I wanted to answer the

following questions:

1 Out of roughly 250 trading days in a calendar year, how

many trading days contributed to generating all of the

net vertical price movement during the course of a

calendar year?

NET UP DAYS

2 If the net vertical price movement were generated from

a particularly small number of trading days, is this In a down year, I determined how many net down days

phenomenon unique to the stock market, or does it contributed to making the lowest closing price for that year.

occur in other markets as well? A net down day is a day that produced a low that was lower

than the previous lowest low made up to that point during that

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V17:12 (529-532): Markets Don’t Trend, They Burst by K.D. Angle

calendar year. With these num-

bers in hand, I then compared

those net up or down days as a

percentage of the 250-odd total

trading days for that year. Take a

look at the Standard & Poor’s

500 index market:

CALENDAR MARKET TOTAL NET PERCENT OF

YEAR DIRECTION DAYS TOTAL DAYS

1983 Up 42 16.8%

1984 Down 23 9.2

1985 Up 26 10.4

1986 Up 30 12.0

1987 Up 42 16.8

1988 Up 20 8.0

1989 Up 48 19.2

1990 Down 24 9.5

1991 Up 26 10.4

1992 Up 15 6.0

1993 Up 21 8.4

1994 Down 7 2.8

1995 Up 80 32.0

1996 Up 29 11.6

1997 Up 41 16.4

1998 Up 41 16.4

As you can see, the fewest

trading days that generated all

of the vertical price movement

for the year occurred in 1994,

with only seven days, or 2.8%,

of the total year’s trading days.

The greatest number of trading

days that contributed to verti-

cal price movement occurred

in 1995, when 80 days, or 32%,

of the year’s total trading days

generated all of the vertical

price movement.

On average, 32 trading days,

or 12.88%, of the total trading

days in an average year for the

S&P 500 generates 100% of

the vertical net change for the

year, regardless if the market is

moving up or down. This study

indicates that a trader trying to

take advantage of all of the

vertical price movement in a

typical calendar year will be

bored a great deal of the time,

since the market is going no-

where 87.12% of the time.

Next, I checked three other

major markets to determine if

what I had found in the S&P

LISA HANEY

was the rule or the exception.

OTHER MARKETS

Using the same criteria I used to

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V17:12 (529-532): Markets Don’t Trend, They Burst by K.D. Angle

study the S&P 500, I generated Figures 1, 2, and 3, a 20%

comparison of coffee, Treasury bonds, and the yen. I noted Coffee

18%

the relative consistency of the average percentage of net days, Net Days

PERCENT OF ALL TRADING DAYS

going up or down: 12% +/-1%. 16%

14%

Markets don’t trend; they burst. 12%

They generate the vast majority of

10%

their movement in only 12% of Average = 11.3%

their trading days. 8%

6%

In addition to the markets discussed previously, I looked at 4%

most of the major futures markets available. Of those I

2%

examined, all exhibited similar burstlike characteristics; nearly

all of their vertical price movement was generated in only 0%

1977 1982 1987 1992 1997

about 12% of the trading days during the course of a calendar YEAR

year. I concluded this is one reason why the long-term trend-

following strategies of the very large trading managers suc- FIGURE 1: COFFEE, DAYS OF MOVEMENT. When you count the days that actually led to

new highs and new lows, you’ll find that, in most markets, only about 12% of trading days

ceed, while those trying to time the market (generally small

contribute to net price movement, up or down. For coffee, it was 11.3%.

individual traders) are not usually rewarded for their efforts.

But if this burst effect is inherent within all markets, how

can the small trader with smaller levels of capital be success-

ful if significant vertical price movement occurs so seldom? In designing an appropriate trading strategy for small

individual clients who want to use their own accounts, I

USING THE BURST EFFECT wanted to avoid entering the market during high levels of

As appealing as the low-maintenance qualities of long-term price volatility and instead enter when low volatility worked

trend-following strategies are, small individual traders should to my advantage. Most long-term trend-following strategies

accept the fact that they require large exit stops. This means that are in the market all of the time tend to reverse themselves

greater risk per trade and the necessity of a large pool of when a large degree of volatility comes into the market. A

trading capital if the trader is going to have a small risk trade exit point must be outside the point at which price

relative to capital. If, on average, 12% of the trading days volatility occurred to make any sense. An exit stop inside this

generates all of the net vertical price movement during a range of high volatility will tend to bounce the trader out

calendar year, you have about a one-in-eight chance of prematurely and actually add more risk to the program in an

predicting when this net price movement might occur. These attempt to reduce losses.

are not good odds. We actively look for periods when price activity is rela-

25% 30%

Treasury Bonds Yen

Net Days Net Days

25%

PERCENT OF ALL TRADING DAYS

20%

PERCENT OF TRADING DAYS

20%

15%

15%

10%

Average = 13.7%

10%

Average = 12%

5%

5%

0% 0%

1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997

YEAR YEAR

FIGURE 2: TREASURY BONDS, DAYS OF MOVEMENT. Similarly, for Treasury bonds, it was FIGURE 3: YEN, DAYS OF MOVEMENT. And for yen, it was 13.7%.

12% even.

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V17:12 (529-532): Markets Don’t Trend, They Burst by K.D. Angle

tively quiet. An easy way to determine if price volatility is following trading programs, long-term trading certainly did

currently low is by comparing last week’s price range to last not benefit those in the stock market between 1929 and 1955.

month’s price range. Generally, when the weekly price range It took 26 years for stocks to finally make a new market high.

exceeds the monthly price range, there are significant levels However, if you don’t have the necessary trading capital to

of price volatility and it’s a good time to avoid the market, at employ a long-term trend-following strategy, paying atten-

least when using a relatively small trading account. We look tion to when volatility is absent in the market should go a long

to enter when price volatility is low or nonexistent. way in improving your chances for success.

During a quiet period in the market, I can concentrate on

the direction to position myself. I define the major trend by Kelly Angle, CTA, is president of K.D. Angle & Co.

using a simple long-term moving average of at least three to

four months. If prices are trading above this moving average, †See Traders’ Glossary for definition S&C

the greatest burst days are generally going to be in the up

direction, while the greatest down burst days are most often

going to be small and much shorter in duration because they

run counter to the major trend. By looking to enter new

positions during periods of low volatility, I have the oppor-

tunity to use relatively small exit stops, which is the edge that

a small trading account must have in order to generate a better

probability of producing positive results over time.

SUMMARY

Markets don’t trend; they burst. They generate the vast

majority of their movement in only 12% of their trading days.

While the tendency for prices to burst or move quickly in a

short period may favor the in-the-market, long-term trend-

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

You might also like

- @TradersLibrary2 Monster Stock Lessons 2020 202 John BoikDocument111 pages@TradersLibrary2 Monster Stock Lessons 2020 202 John BoikKartik Iyer91% (11)

- Thackray Market Letter 2010 AugustDocument7 pagesThackray Market Letter 2010 AugustprestigetradeNo ratings yet

- New Complete Market Breadth IndicatorsDocument30 pagesNew Complete Market Breadth Indicatorsemirav2100% (2)

- An Introduction To Stock Market IndexesDocument5 pagesAn Introduction To Stock Market IndexesAlexis SinghNo ratings yet

- The Amazing Story of Stock Market SeasonalityDocument5 pagesThe Amazing Story of Stock Market SeasonalityBrook Rene JohnsonNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of The Relative Strength IndexDocument6 pagesAn Investigation of The Relative Strength IndexiswardiNo ratings yet

- Technical Analysis, The Markets and Moving AveragesDocument4 pagesTechnical Analysis, The Markets and Moving AveragesShashikant BhujadeNo ratings yet

- Adamodar MkttimingDocument56 pagesAdamodar MkttimingMardiko NumbraNo ratings yet

- Explanation of Net Change in Open InterestDocument8 pagesExplanation of Net Change in Open Interestaniljain16No ratings yet

- Market StrengthDocument7 pagesMarket Strengthsidd2208No ratings yet

- Stock Volatility PerspectiveDocument6 pagesStock Volatility PerspectiveTadhg NealonNo ratings yet

- BreadthDocument8 pagesBreadthemirav2No ratings yet

- Pivot Point Analysis in Stock TradingDocument5 pagesPivot Point Analysis in Stock TradingSIightlyNo ratings yet

- Dalal Street English Magazine Preview Issue 22Document14 pagesDalal Street English Magazine Preview Issue 22vikram0mg100% (1)

- Index: Stock Market Key TermsDocument49 pagesIndex: Stock Market Key TermsSOMINI ENTERPRISESNo ratings yet

- John P. Hussman, PH.D.: The Future Is NowDocument6 pagesJohn P. Hussman, PH.D.: The Future Is NowdickygNo ratings yet

- Market Tops Booklet PDFDocument16 pagesMarket Tops Booklet PDFAzraf HamidNo ratings yet

- Time Varying Volatility in The Indian Stock Market VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Day of The Week Effect BackupDocument18 pagesTime Varying Volatility in The Indian Stock Market VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Day of The Week Effect BackupSrinu BonuNo ratings yet

- LFM Commentary December 2009Document10 pagesLFM Commentary December 2009eclaneNo ratings yet

- The Dow Theory (Part 1) : Technical AnalysisDocument24 pagesThe Dow Theory (Part 1) : Technical AnalysisHarsh MisraNo ratings yet

- Broschuere The Basics of Commodities EnglischDocument12 pagesBroschuere The Basics of Commodities EnglischMohamed BhathurudeenNo ratings yet

- Email Nomura AssetDocument6 pagesEmail Nomura AssetWyllian CapucciNo ratings yet

- TOP Stocks: Adversity Leads To OpportunityDocument168 pagesTOP Stocks: Adversity Leads To OpportunityJoyce Dick Lam PoonNo ratings yet

- Review of Literature On Stock Market IndicesDocument6 pagesReview of Literature On Stock Market Indicesafmabzmoniomdc100% (1)

- Market Indicator of Technical AnalysisDocument13 pagesMarket Indicator of Technical AnalysisMuhammad AsifNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Stock Market IndicesDocument3 pagesAn Introduction To Stock Market IndicesGopi KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Stock Cycles: Why Stocks Won't Beat Money Markets over the Next Twenty YearsFrom EverandStock Cycles: Why Stocks Won't Beat Money Markets over the Next Twenty YearsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Chapter 7 Market Price BehaviorDocument57 pagesChapter 7 Market Price BehaviorCezarene FernandoNo ratings yet

- Weitz Funds 4 Q2008 LetterDocument5 pagesWeitz Funds 4 Q2008 LetterfwallstreetNo ratings yet

- WpviewerDocument9 pagesWpviewernloucaNo ratings yet

- Market Commentary 7-30-12Document3 pagesMarket Commentary 7-30-12CLORIS4No ratings yet

- Answer:: A Basic DefinitionDocument3 pagesAnswer:: A Basic DefinitionchandravadiyaketanNo ratings yet

- Market Haven Monthly 2011 FebruaryDocument10 pagesMarket Haven Monthly 2011 FebruaryMarketHavenNo ratings yet

- Stock Exchange IndicesDocument19 pagesStock Exchange IndicesBunu MarianaNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics and Stock Market TimingDocument31 pagesMacroeconomics and Stock Market Timingjl123123No ratings yet

- April 2011 CommentaryDocument4 pagesApril 2011 CommentaryMKC GlobalNo ratings yet

- Stock Volatility Perspective4Document5 pagesStock Volatility Perspective4annawitkowski88No ratings yet

- The Broyhill Letter: Executive SummaryDocument3 pagesThe Broyhill Letter: Executive SummaryBroyhill Asset ManagementNo ratings yet

- Fixed Income DerivativesDocument24 pagesFixed Income DerivativesKrishnan ChariNo ratings yet

- Secondary Stock Indexes GuideDocument2 pagesSecondary Stock Indexes Guideadrien_ducaillouNo ratings yet

- Book Trading Focus FinalDocument85 pagesBook Trading Focus FinalIan Moncrieffe86% (7)

- Larry Williams - Trading Patterns For Stocks and CommoditiesDocument8 pagesLarry Williams - Trading Patterns For Stocks and CommoditiesAlex Grey83% (6)

- J. Peter Steidlmayer:: in Step With The MarketsDocument6 pagesJ. Peter Steidlmayer:: in Step With The Marketsdoron1100% (4)

- Yardeni Stock Market CycleDocument36 pagesYardeni Stock Market CycleOmSilence2651100% (1)

- Xtrades Members Select Weekend Analysis Report Part 1, 2, & 3Document9 pagesXtrades Members Select Weekend Analysis Report Part 1, 2, & 3Anonymous MulticulturalNo ratings yet

- Joi Evaluating Index Tradeability 201209Document11 pagesJoi Evaluating Index Tradeability 201209Philip LeonardNo ratings yet

- F2011 OptimalMomentum2 GaryantonacciDocument28 pagesF2011 OptimalMomentum2 GaryantonacciNagy ZoltánNo ratings yet

- Home Work - ZADocument3 pagesHome Work - ZAvgfhvgNo ratings yet

- 1 - Dollar Cost Averaging: Stock Market TimingDocument30 pages1 - Dollar Cost Averaging: Stock Market TimingkenNo ratings yet

- 20-Modified Volume-Price Trend IndicatorDocument7 pages20-Modified Volume-Price Trend Indicatorvip_thb_2007100% (1)

- Market Tops BookletDocument16 pagesMarket Tops BookletDebarshi MajumdarNo ratings yet

- Volatality in Stock MarketDocument16 pagesVolatality in Stock Marketpratik tanna0% (1)

- Key Financial Terms and RatiosDocument16 pagesKey Financial Terms and RatiosShravan KumarNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Turn-Of-The-Month, Window Dressing, Market AnomaliesDocument19 pagesKeywords: Turn-Of-The-Month, Window Dressing, Market Anomaliespderby1No ratings yet

- Nick Train The King of Buy and Hold PDFDocument13 pagesNick Train The King of Buy and Hold PDFJohn Hadriano Mellon FundNo ratings yet

- College of Business Administration University of Pittsburgh: Risk and ReturnDocument9 pagesCollege of Business Administration University of Pittsburgh: Risk and ReturnAbi VillaNo ratings yet

- August 022010 PostsDocument150 pagesAugust 022010 PostsAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- The WSJ Guide to the 50 Economic Indicators That Really Matter: From Big Macs to "Zombie Banks," the Indicators Smart Investors Watch to Beat the MarketFrom EverandThe WSJ Guide to the 50 Economic Indicators That Really Matter: From Big Macs to "Zombie Banks," the Indicators Smart Investors Watch to Beat the MarketRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Bear Market Day Trading Strategies: Day Trading Strategies, #1From EverandBear Market Day Trading Strategies: Day Trading Strategies, #1Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Pring PeaksAndTrophs PDFDocument5 pagesPring PeaksAndTrophs PDFbillthegeekNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Fibonacci Price Clusters and Timing on the CBOT mini-Sized DowDocument45 pagesIntroduction to Fibonacci Price Clusters and Timing on the CBOT mini-Sized DowraviinterNo ratings yet

- Java Collections FrameworkDocument44 pagesJava Collections FrameworkAdarshNo ratings yet

- Out BulletsDocument1 pageOut BulletsraviinterNo ratings yet

- PublicationDocument25 pagesPublicationraviinterNo ratings yet

- This Is A Pageout Stored As Resource in Runtime DatabaseDocument5 pagesThis Is A Pageout Stored As Resource in Runtime DatabaseraviinterNo ratings yet

- Selenium NotesDocument2 pagesSelenium NotesraviinterNo ratings yet

- TraderDocument2 pagesTraderraviinterNo ratings yet

- EnglishDocument2 pagesEnglishraviinterNo ratings yet

- Nava Graha Stotram in TeluguDocument2 pagesNava Graha Stotram in TeluguBhamidipati PremNo ratings yet

- Jesse Livermore - Reminiscences of A Stock OperatorDocument238 pagesJesse Livermore - Reminiscences of A Stock OperatoraardeiNo ratings yet

- Software Test Report TemplateDocument10 pagesSoftware Test Report TemplateraviinterNo ratings yet

- Software Test Report TemplateDocument10 pagesSoftware Test Report TemplateraviinterNo ratings yet

- Alphabar 1.0 by RedBlackProductionDocument3 pagesAlphabar 1.0 by RedBlackProductionManic AmalgamNo ratings yet

- MailgrepDocument3 pagesMailgrepraviinterNo ratings yet

- Testing TechniquesDocument13 pagesTesting TechniquesraviinterNo ratings yet

- Fruit WashDocument2 pagesFruit WashraviinterNo ratings yet

- QTP1Document5 pagesQTP1raviinterNo ratings yet

- Rest AssuredDocument25 pagesRest AssuredraviinterNo ratings yet

- Personalizaciondecontenidoenservidor ATGDocument10 pagesPersonalizaciondecontenidoenservidor ATGRobert MorkosNo ratings yet

- Volume Profile, Market Profile, Order Flow - Next Generation of DaytradingDocument207 pagesVolume Profile, Market Profile, Order Flow - Next Generation of DaytradingNguyen Tuan93% (14)

- Balance Sheet of Tata Communications: - in Rs. Cr.Document24 pagesBalance Sheet of Tata Communications: - in Rs. Cr.ankush birlaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 - BUSINESS TRANSACTIONS AND THEIRANALYSIS AS APPLIED TO THEDocument34 pagesChapter 9 - BUSINESS TRANSACTIONS AND THEIRANALYSIS AS APPLIED TO THEmarkalvinlagunero1991No ratings yet

- Accounting & FinanceDocument501 pagesAccounting & FinancejackNo ratings yet

- Behavioral FinanceDocument31 pagesBehavioral FinanceSwathi Velisetty25% (4)

- Value Investor Insight - May 31, 2013Document10 pagesValue Investor Insight - May 31, 2013vishubabyNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics and Fianancial AnalysisDocument2 pagesManagerial Economics and Fianancial Analysissrihari357No ratings yet

- Inflation Linked Bonds - 9-15 PDFDocument27 pagesInflation Linked Bonds - 9-15 PDFClutch Derivative100% (1)

- Ross FCF 11ce Ch19Document24 pagesRoss FCF 11ce Ch19jessedillon234567No ratings yet

- Meaning of LeverageDocument5 pagesMeaning of LeverageAdeem AshrafiNo ratings yet

- FIN622 Online Quiz - PdfaDocument531 pagesFIN622 Online Quiz - Pdfazahidwahla1100% (3)

- Basic Accounting PrinciplesDocument2 pagesBasic Accounting Principlesaashir chNo ratings yet

- CMA Exam Content Specification OutlinesDocument16 pagesCMA Exam Content Specification OutlinesMolly SchneidNo ratings yet

- Varian9e LecturePPTs Ch38 PDFDocument76 pagesVarian9e LecturePPTs Ch38 PDF王琦No ratings yet

- CH 29Document6 pagesCH 29Roselle Mae AgcaoiliNo ratings yet

- Shopping Mall Business PlanDocument4 pagesShopping Mall Business PlanJarvys DoumbeNo ratings yet

- Finance Interview QuestionsDocument15 pagesFinance Interview QuestionsJitendra BhandariNo ratings yet

- Dakhal Dar Maqoolat by Ibn e InshaDocument188 pagesDakhal Dar Maqoolat by Ibn e InshaWaqar AzeemNo ratings yet

- Metastock RSC Exploration PDFDocument5 pagesMetastock RSC Exploration PDFRaam Mk100% (1)

- Teaching Note 00-04: Girsanov'S Theorem in Derivative PricingDocument16 pagesTeaching Note 00-04: Girsanov'S Theorem in Derivative PricingVeeken ChaglassianNo ratings yet

- Explaining The Price Anomaly of KRX Preferred StocksDocument11 pagesExplaining The Price Anomaly of KRX Preferred Stockstjl84No ratings yet

- Financial Planning and StrategiesDocument5 pagesFinancial Planning and StrategiesHads LunaNo ratings yet

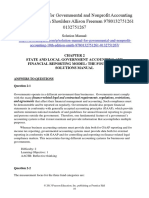

- Governmental and Nonprofit Accounting 10th Edition Smith Solution ManualDocument27 pagesGovernmental and Nonprofit Accounting 10th Edition Smith Solution Manualconsuelo100% (21)

- Ia Vol 3 Valix 2019 Solman 2 PDF FreeDocument105 pagesIa Vol 3 Valix 2019 Solman 2 PDF FreeLJNo ratings yet

- Prerev FOREX 2019Document8 pagesPrerev FOREX 2019RojParcon50% (4)

- The Elements of Financial Structure and Their Impact On The Market Value of The Firm Economic. Case Study of The Debts of Saidal Group (1999-2014)Document27 pagesThe Elements of Financial Structure and Their Impact On The Market Value of The Firm Economic. Case Study of The Debts of Saidal Group (1999-2014)Sweet AngeNo ratings yet

- IBC (Edition 3)Document369 pagesIBC (Edition 3)Kinnar ShahNo ratings yet

- Forward FuturesDocument81 pagesForward FuturesUTTAM KOIRALANo ratings yet

- Mutual Fund Screener India - Real Time MF Analysis Tool - TickertapeDocument1 pageMutual Fund Screener India - Real Time MF Analysis Tool - TickertapePrasanna GowriNo ratings yet

- Advanced Financial Accounting 12th Edition Christensen Solutions ManualDocument25 pagesAdvanced Financial Accounting 12th Edition Christensen Solutions ManualWilliamDavisdqbs100% (53)