Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Potential Stagnation and Decline in Return On Investment Identifying Medium-Term Issues in An Intensive English Program in A Japanese University

Uploaded by

Global Research and Development ServicesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Potential Stagnation and Decline in Return On Investment Identifying Medium-Term Issues in An Intensive English Program in A Japanese University

Uploaded by

Global Research and Development ServicesCopyright:

Available Formats

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

Gavin Lynch, 2019

Volume 5 Issue 1, pp. 656-669

Date of Publication: 1st May 2019

DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2019.51.656669

This paper can be cited as: Lynch, G., (2019). Potential Stagnation and Decline in Return on Investment

~Identifying Medium-Term Issues in an Intensive English Program in a Japanese University~.

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 5(1), 656-669.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International

License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a

letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA.

POTENTIAL STAGNATION AND DECLINE IN RETURN ON

INVESTMENT ~IDENTIFYING MEDIUM-TERM ISSUES IN AN

INTENSIVE ENGLISH PROGRAM IN A JAPANESE

UNIVERSITY~

Gavin Lynch

Kanazawa Seiryo University, Kanazawa, Japan

lynch@seiryo-u.ac.jp

Abstract

This research reports on five years of results of IELTS (International English Language Testing

System) testing taken by first year university students in a Japanese university. The data

analyzed in previous papers was from economics majors taking higher level English classes in

the academic years of 2013 and 2014, and then in 2016 and 2017 by liberal arts

(culture/tourism/English) majors in a new department whose initial focus was English. Lynch

(2017) reported that “return on investment (ROI) in education increases when students are given

choices in their education”, confirming earlier results found by Lynch & McKeurtan (2011), and

Spokes (1989). Furthermore, teaching in a more intensive way (using a quarter system rather

than a semester system) was found to give greater ROI. This study goes further and examines a

further year of results, finding that stagnation and some decline in results began. This may

indicate that the initial high results may have been partly due to special circumstances present in

the new department, or that new circumstances have appeared which limited academic gains.

Results are reported and discussed. Data and a discussion including class student-teacher ratio

is added, giving a new direction to the research. Overall, despite decline in results, it was found

that the continuing the intensive program is still worth it in terms of ROI for some years.

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 656

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

Findings also included how changing university entrance examination requirements, teacher

experience and burnout, and temporary dips in shown ability can all be important points of

research.

Keywords

IELTS, Intensive Program, Return on Investment, Stagnation/Decline in Results, Four-Skills

Evaluation

1. Introduction: Stagnation and Decline Noticed in Results over Time

Lynch (2015a) (2015b) compared groups of students and investigated their performance

in IELTS examinations in two academic years (2013 and 2014) for economic majors in a

university in Japan. The paper looked at results in terms of return on investment (ROI), with

investment being teaching hours (and hired staff/teacher ability), and return being the IELTS

examination scores students obtained, which is an international English skills test (IELTS, 2018).

A further paper (Lynch, 2017) included new data with more years of students’ IELTS

performance, allowing greater insights. A limitation was that the new data was taken from a

different department (as the program in the first department was closed). Despite this, some

comparisons were able to be made as students were all in their first year in the same university,

with both groups not yet fully embarking on their major subject studies until their second or third

years. Other characteristics of students were observed to be, or partly assumed to be, similar.

This paper adds an additional data set, that of the 2018 academic year. The 2018 data

showed a fall in some scores compared to previous years, and this warranted investigation and

research. This decline had been partly part predicted/anticipated and lower student-teacher ratios

were put in place in advance to avoid such academic decline. However, this strategy was not

successful in all cases, and it was not shown that lower student-teacher numbers resulted in

higher academic achievement across the board in terms of English skills in the IELTS

examination.

2. Background

The IELTS scores reported in this paper are from the academic years of 2013, 2014,

2016, 2017, and 2018. The students are separated into the “Economics Group”, (the former two

years) and the “Liberal Arts Group” (the latter three years). The Economics Group decided (self-

selected) to enter what was regarded and explained as being a challenging class (referred to as

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 657

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

the Super Class) and have a goal of gaining a high score in IELTS of 5.5 points. The reward (for

those few who succeeded) was to be allowed to study abroad as part of the university subsidised

international educational program. The students in this group tended to be high performers when

compared with their peers in the same department. The Liberal Arts Group were students in a

new university department opened in 2016, and were from the 2016, 2017 and 2018 academic

years. This department was also advertised/regarded as being challenging (and was more

difficult to enter than the other departments). Study abroad was included in the curriculum for all

students, but they were told that a high IELTS score would give them an advantage/priority when

choosing their destination/country from a list, as each destination offered only a limited number

of places. They were told to aim for (but not strictly required to) a score of 6.0 points, a

department recommendation/expectation.

Details about these groups, teaching time and frequency etc., are given in Lynch (2017).

In brief, the Economics Group had 60 English education classes before IELTS 1 (their first

IELTS), and then the same again (another 60), making a total of 120 classes prior to IELTS 2

(their second IELTS examination). On the other hand, the Liberal Arts Group experienced 75

classes of English education before IELTS 1, and 150 classes before IELTS 2, a 25% increase

when compared to the Economics Group. The Economics Group took the IELTS at the end of

each semester, in August and then again in January of each year. The Liberal Arts Group took

the IELTS at the end of each quarter (the first in June, and the second in August). One class is 90

minutes in duration. The Japanese academic year begins in April.

This paper adds data for the 2018 year to the previous research. A big change was that

more new teachers were hired, and class numbers (i.e., the number of students per teacher) were

reduced due to this. This situation is one of the items of core interest to this and future studies.

It can be estimated that the Economics Group began their studies at an approximate

average level of at least 3.5 points, while the Liberal Arts Group began at an average level of

approximately 4.0 IELTS points, although individual students varied and the above figures are

estimates by the educators in charge/the department.

3. Data Collection, Analysis and Results

3.1 Data Collection: IELTS Scores

This is a continuation and expansion of the Lynch (2017) paper. The official IELTS

scores were collected, and the data is presented below as graphs/figures (of the mean overall

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 658

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

scores as well as those for each skill) and tables are shown below, with other data (variations in

ability, SD, and p-values) included. An overall, general pattern can be observed, part of which is

predictable based on the number of hours and intensity of tuition. Average scores for 2013 and

2014 were lower than for years 2016, 2017 and 2018, forming two “groups” of data, one from

the former dates, and the other from the latter. This in itself shows that changing the method and

amount of education provided to students produced clear benefits. Looking at the latter years

(2016, 2017 and 2018), the beginning of score stagnation and decline can be observed.

IELTS Overall Scores

(1st, 2nd test comparison)

5.50

5.00

4.50

4.00

3.50

2013 2014 2016 2017 2018

Average scores Average scores

(IELTS 1st) (IELTS 2nd)

Figure 1: Averaged Overall IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 659

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

Table 1: Averaged Overall IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

2013 2014 2016 2017 2018

Overall Overall Overall Overall Overall

n 48 18 36 37 57

Average scores

3.97 4.17 5.03 4.80 4.65

(IELTS 1st)

Stdev (1st) 0.559 0.42 0.366 0.376 0.37

Average scores

4.38 4.53 5.14 5.15 5.03

(IELTS 2nd)

Stdev (2nd) 0.467 0.436 0.355 0.349 0.360

p-value p=0.0002 p=0.0165 p=0.1998 p<0.0001 p<0.0001

Increase 0.41 0.36 0.11 0.35 0.38

IELTS Listening Scores

(1st, 2nd test comparison)

5.50

5.00

4.50

4.00

3.50

2013 2014 2016 2017 2018

Listening Listening Listening Listening Listening

Average scores Average scores

(IELTS 1st) (IELTS 2nd)

Figure 2: Averaged Listening IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

Table 2: Averaged Listening IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 660

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

2013 2014 2016 2017 2018

Listening Listening Listening Listening Listening

n 48 18 36 37 57

Average scores

4.24 4.33 5.08 4.78 4.62

(IELTS 1st)

Stdev (1st) 0.357 0.569 0.500 0.400 0.607

Average scores

4.20 4.14 5.04 5.20 5.03

(IELTS 2nd)

Stdev (2nd) 0.572 0.614 0.498 0.492 0.530

p-value p=0.620 p=0.3424 p=0.7348 p<0.0001 p=0.0001

Increase -0.04 -0.19 -0.04 0.42 0.40

IELTS Reading Scores

(1st, 2nd test comparison)

5.50

5.00

4.50

4.00

3.50

2013 2014 2016 2017 2018

Reading Reading Reading Reading Reading

Average scores Average scores

(IELTS 1st) (IELTS 2nd)

Figure 3: Averaged Reading IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 661

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

Table 3: Averaged Reading IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

2013 2014 2016 2017 2018

Reading Reading Reading Reading Reading

n 48 18 36 37 57

Average scores

4.25 4.58 5.29 4.93 4.98

(IELTS 1st)

Stdev (1st) 0.450 0.600 0.498 0.699 0.582

Average scores

4.64 5.06 5.31 5.32 5.08

(IELTS 2nd)

Stdev (2nd) 0.434 0.684 0.636 0.543 0.653

p-value p<0.0001 p=0.0319 p=0.8823 p=0.091 p=0.0009

Increase 0.39 0.47 0.01 0.39 0.10

IELTS Writing Scores

(1st, 2nd test comparison)

5.50

5.00

4.50

4.00

3.50

2013 Writing 2014 Writing 2016 Writing 2017 Writing 2018 Writing

Average scores Average scores

(IELTS 1st) (IELTS 2nd)

Figure 4: Averaged Writing IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 662

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

Table 4: Averaged Writing IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

2013 2014 2016 2017 2018

Writing Writing Writing Writing Writing

n 48 18 36 37 57

Average scores

4.68 3.78 4.99 4.88 4.78

(IELTS 1st)

Stdev (1st) 0.455 0.691 0.528 0.477 0.535

Average scores

4.25 4.42 4.82 5.26 5.18

(IELTS 2nd)

Stdev (2nd) 0.676 0.575 0.55 0.466 0.361

p-value p=0.0004 p=0.0048 p=0.1853 p=0.0009 p=0.7074

Increase -0.43 0.64 -0.17 0.38 0.40

IELTS Speaking Scores

(1st, 2nd test comparison)

5.50

5.00

4.50

4.00

3.50

2013 2014 2016 2017 2018

Speaking Speaking Speaking Speaking Speaking

Average scores Average scores

(IELTS 1st) (IELTS 2nd)

Figure 5: Averaged Speaking IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 663

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

Table 5: Averaged Speaking IELTS Scores, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018

2013 2014 2016 2017 2018

Speaking Speaking Speaking Speaking Speaking

n 48 18 36 37 57

Average scores

3.90 3.81 4.51 4.32 4.25

(IELTS 1st)

Stdev (1st) 0.765 0.689 0.541 0.615 0.560

Average scores

4.07 4.50 5.21 4.53 4.84

(IELTS 2nd)

Stdev (2nd) 0.737 0.728 0.625 0.471 0.649

p-value p=0.2704 p=0.0062 p<0.0001 p=0.1035 p=0.0362

Increase 0.18 0.69 0.69 0.20 0.59

3.2 Data Collection: Student-Teacher Ratios and Results

The number of students assigned per teacher is given in this section, along with related

data including the students’ estimated beginning ability along with their end results for easier

cross-reference. It should be added here that students in the Liberal Arts Group were assigned to

different classes using entrance examination data and other information, which was then used to

estimate the ability (beginning level) of the students. There are four possible starting classes each

with an associated approximate starting ability in terms of IELTS. Those classes are as in Table

6, below:

Table 6: Liberal Arts Group Placement Classes (2016, 2017, 2018)

Class G1 G2 G3 G4

(Est.) Beginning Ability

4 4.5 5 5.5

(IELTS)

Further data obtained was collated, and included the number of students in each class,

teacher numbers, student-teacher ratios, and student scores for each ability for the 2016, 2017,

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 664

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

and 2018 academic years. This data is presented below in Tables 7, 8 and 9, with the following

information:

There are five taught skill classes (listening, reading, writing, speaking, phrases &

expressions)

S-T means Student-Teacher

P&E means Phrase and Expression (vocabulary) classes

G4 numbers are initially 0, as no students were deemed skilled enough to start in those

classes.

Table 7: Liberal Arts Group 2016 Data

G1 G2 G3

2016 G1 G2 G3 G4

S-T ratio S-T ratio S-T ratio

Students 2016 (n=36) 13 21 2 0

Listening Teachers 1 13 1 21 1 2 0

Final Ability (Listening IELTS) 4.7 5.2 5.8

Reading Teachers 1 13 1 21 1 2 0

Final Ability (Reading IELTS) 4.9 5.5 6.3

Writing Teachers 1 13 1 21 1 2 0

Final Ability (Writing IELTS) 4.7 4.9 4.8

Speaking Teachers 1 13 1 21 1 2 0

Final Ability (Speaking IELTS) 4.9 5.3 5.8

P&E** Teachers 1 13 1 21 1 2 0

Final Ability (Overall IELTS) 4.8 5.23 5.63

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 665

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

Table 8: Liberal Arts Group 2017 Data

G1 G2 G3

2017 G1 G2 G3 G4

S-T ratio S-T ratio S-T ratio

Students 2017 (n=37) 23 7 7 0

Listening Teachers 1 23 1 7 1 7 0

Final Ability (Listening IELTS) 5 5.5 5.6

Reading Teachers 1 23 1 7 1 7 0

Final Ability (Reading IELTS) 5 5.7 5.9

Writing Teachers 2 11.5 1 7 1 7 0

Final Ability (Writing IELTS) 5.1 5.5 5.5

Speaking Teachers 1 23 1 7 1 7 0

Final Ability (Speaking IELTS) 4.4 4.5 5.1

P&E** Teachers 1 23 1 7 1 7 0

Final Ability (Overall IELTS) 4.88 5.3 5.5

Table 9: Liberal Arts Group 2018 Data

G1 G2 G3

2018 G1 G2 G3 G4

S-T ratio S-T ratio S-T ratio

Students 2018 (n=57) 24 20 13 0

Listening Teachers 2 12 2 10 1 13 0

Final Ability (Listening IELTS) 4.6 5.1 5.6

Reading Teachers 2 12 2 10 1 13 0

Final Ability (Reading IELTS) 4.7 5.2 5.7

Writing Teachers 3 8 3 6.67 1 13 0

Final Ability (Writing IELTS) 5.1 5.3 5.2

Speaking Teachers 2 12 2 10 1 13 0

Final Ability (Speaking IELTS) 4.5 5.1 5.2

P&E** Teachers 2 12 2 10 1 13 0

Final Ability (Overall IELTS) 4.75 5.14 5.38

4. Results and Discussion

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 666

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

Lynch (2017) has already reported on comparisons up to 2017. It was shown that, for the

2013 to 2017 data set, that an increase in teaching hours in an intensive program produces good

ROI, and should be continued. It was also seen that, for the 2017 students overall results, their

first IELTS examination was lower than the previous year, but they could catch up over the next

couple of months when taking part in the same program with the same goals.

What is interesting is the inclusion of the 2018 set of data showing that the above is not

always true. It can be seen (from the overall scores) that both the IELTS 1 and IELTS 2 were

lower than previous years. In other words, these students performed relatively poorly in both the

first and the second IELTS examination, compared to the years before them. Looking at each of

the skills, it was noticed that this was true for each skill, except for speaking.

There are some possible reasons for this:

1. This group of students included some who were accepted at a lower entrance level than

previous years. (This is a fact, as a handful of students were accepted to the department,

with lower scores).

2. (Partly to counter the above) The number of teachers were increased to decrease the

teacher to student number ratio. However, it was possible that those teachers were not as

highly skilled or experienced as the ones who were there from the beginning. The

improved student-teacher ratio did not have a clear impact, meaning that simply throwing

resources at the problem did not result in a suitable solution.

3. It could be that some of the teachers who were in the new department from the beginning

may showing signs of burnout, lower motivation, or a lack of urgency. On the other hand,

it may be that the new teachers added were not skilled or experienced enough to offset the

increased number of students. This needs further investigation, and can be done by

reporting the results of each teacher’s class, rather than the entire group or subgroups.

4. The speaking results increasing in 2018 from 2017 (while the other skills declined) could

be explained by students having performed particularly poorly in 2017. Therefore, when

comparing 2017 and 2018, it was relatively easy for 2018 students to score more highly

than students had done one year previously.

Overall, the scores have been decreasing from 2016 for the first IELTS examination, and

from 2017 for the second. The data suggests that changing the numbers of students in a class,

i.e., student-teacher ratios, is not an effective way of improving student performance across the

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 667

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

board. In other words, this method results in a poor ROI (return on investment), and deeper

investigation is warranted.

5. Conclusions and Further Study

Consideration of the results led to the following conclusions:

1. The highs in terms of students’ IELTS test performance were seen in 2016 and 2017, with a

decreasing trend noticed to 2018.

2. Improving (decreasing) the student-teacher ratio does not appear to show a good return in

investment, and the return can even be a negative one. This (reasons for the poor ROI)

needs more investigation.

3. The data seems to give a warning to the university department as it indicates a stagnation

and even a decline in results, with no apparent solution being suggested.

4. The background of the students was put forward as a point of further study. However, as

this is a comparative study, and the students (students in both groups) are all from the same

area, with similar backgrounds, this is not deemed to be a potential productive line of

inquiry.

Further study will expand the data set, and look into the performance of individual

teachers (in the cases were classes were split with teachers assigned to each), investigate if a

decline is common after the initial euphoria and excitement of a new project (department) is

launched, and to see if solutions to the results stagnation have been offered elsewhere.

References

IELTS.org. (2018, October 18). IELTS Introduction. Retrieved from https://www.ielts.org/what-

is-ielts/ielts-introduction

Lynch, G. (2017). Return on Investment Shown in IELTS Scores in an Intensive English

Program in a Japanese University. Journal of Kanazawa Seiryo University, 51 (1), 81-88.

Lynch, G. (2015a). Who and What Should Place Students in High-Stakes English Classes?

Students Opinions and Results of IELTS and TOEIC International Testing. Kanazawa

Seiryo University Human Sciences, 9 (1), 91-97.

Lynch, G. (2015b). Self-Selecting Students Rapidly Improve and Then Maintain IELTS-Shown

English Ability, IELTS International Testing and Student Awareness. Journal of

Kanazawa Seiryo University, 49 (1), 83-87.

Lynch, G., & McKeurtan, M. (2011). Motivation in the Curriculum: Effects of Making Students

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 668

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN 2454-5899

Stakeholders in Tertiary Level English Classes. 20th MELTA International Conference

Proceedings, 386-397.

Spolsky, B. (1989) Conditions for Second Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Available Online at: http://grdspublishing.org/ 669

You might also like

- Examine The Effects of Goods and Services Tax (GST) and Its Compliance: Reference To Sierra LeoneDocument18 pagesExamine The Effects of Goods and Services Tax (GST) and Its Compliance: Reference To Sierra LeoneGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Relationship Between Industrial Policy and Entrepreneurial EcosystemDocument13 pagesAnalyzing The Relationship Between Industrial Policy and Entrepreneurial EcosystemGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Resolving A Realistic Middle Ground Towards The Sustainability Transition in The Global Political and Economic Landscape: A Comprehensive Review On Green CapitalismDocument29 pagesResolving A Realistic Middle Ground Towards The Sustainability Transition in The Global Political and Economic Landscape: A Comprehensive Review On Green CapitalismGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Loss Analysis in Bread Production Process Using Material Flow Cost Accounting TechniqueDocument16 pagesLoss Analysis in Bread Production Process Using Material Flow Cost Accounting TechniqueGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Influence of Iot On Smart LogisticsDocument12 pagesInfluence of Iot On Smart LogisticsGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Interpretation and Justification of Rules For Managers in Business Organizations: A Professional Ethics PerspectiveDocument10 pagesInterpretation and Justification of Rules For Managers in Business Organizations: A Professional Ethics PerspectiveGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Potential Factors Influence Failure of The Village-Owned Business: The Entity Village Autonomy of Indonesian Government's ProgramDocument12 pagesPotential Factors Influence Failure of The Village-Owned Business: The Entity Village Autonomy of Indonesian Government's ProgramGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Effect of Metacognitive Intervention Strategies in Enhancing Resilience Among Pre-Service TeachersDocument12 pagesEffect of Metacognitive Intervention Strategies in Enhancing Resilience Among Pre-Service TeachersGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Perceived Self-Efficacy and Academic Performance of Stem Senior High School StudentsDocument13 pagesPerceived Self-Efficacy and Academic Performance of Stem Senior High School StudentsGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Teacher Educators' Perceptions of Utilizing Mobile Apps For English Learning in Secondary EducationDocument28 pagesTeacher Educators' Perceptions of Utilizing Mobile Apps For English Learning in Secondary EducationGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Challenges in The Implementation of Schoolbased Management of Developing Schools: Basis For A Compliance FrameworkDocument14 pagesChallenges in The Implementation of Schoolbased Management of Developing Schools: Basis For A Compliance FrameworkGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Design and Implementation of An Arabic Braille Self-Learning WebsiteDocument17 pagesDesign and Implementation of An Arabic Braille Self-Learning WebsiteGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Global E-Learning and Experiential Opportunities For Programs and StudentsDocument12 pagesGlobal E-Learning and Experiential Opportunities For Programs and StudentsGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Refining The English Syntax Course For Undergraduate English Language Students With Digital TechnologiesDocument19 pagesRefining The English Syntax Course For Undergraduate English Language Students With Digital TechnologiesGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Using Collaborative Web-Based Maps To Promote Geography Teaching and LearningDocument13 pagesUsing Collaborative Web-Based Maps To Promote Geography Teaching and LearningGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- The Knowledge-Sharing Culture in An Operational Excellence Plant As Competitive Advantage For Forward-Thinking OrganizationsDocument17 pagesThe Knowledge-Sharing Culture in An Operational Excellence Plant As Competitive Advantage For Forward-Thinking OrganizationsGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Bank-Specific and Macroeconomic Determinants of Banks Liquidity in Southeast AsiaDocument18 pagesBank-Specific and Macroeconomic Determinants of Banks Liquidity in Southeast AsiaGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Implementation of Biorhythm Graph With Trigonometric Functions Using PythonDocument8 pagesImplementation of Biorhythm Graph With Trigonometric Functions Using PythonGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Work-Related Problems and Performance Level of Senior High School TeachersDocument22 pagesWork-Related Problems and Performance Level of Senior High School TeachersGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- The Development of Nursing Care Model in Patients With Total Knee Replacement Reconstructive SurgeryDocument17 pagesThe Development of Nursing Care Model in Patients With Total Knee Replacement Reconstructive SurgeryGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Global E-Learning and Experiential Opportunities For Programs and StudentsDocument12 pagesGlobal E-Learning and Experiential Opportunities For Programs and StudentsGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Study of Urban Heat Island in Yogyakarta City Using Local Climate Zone ApproachDocument17 pagesStudy of Urban Heat Island in Yogyakarta City Using Local Climate Zone ApproachGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Effects of Social Media On The Well-Being of TeenagersDocument18 pagesInvestigating The Effects of Social Media On The Well-Being of TeenagersGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Review of Vibration-Based Surface & Terrain Classification For Wheel-Based Robot in Palm Oil PlantationDocument14 pagesReview of Vibration-Based Surface & Terrain Classification For Wheel-Based Robot in Palm Oil PlantationGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- How Bi-Lingual Fathers Support Their Children To Learn Languages at HomeDocument35 pagesHow Bi-Lingual Fathers Support Their Children To Learn Languages at HomeGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Development of A Topical Gel Containing A Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor For Wound Healing ApplicationsDocument15 pagesDevelopment of A Topical Gel Containing A Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor For Wound Healing ApplicationsGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Leadership Initiative To Enrich The Hiv/aids Education For Senior High SchoolsDocument21 pagesLeadership Initiative To Enrich The Hiv/aids Education For Senior High SchoolsIshika JainNo ratings yet

- The Hijiri Calendar and Its Conformance With The Gregorain Calendar by Mathematical CalculationsDocument19 pagesThe Hijiri Calendar and Its Conformance With The Gregorain Calendar by Mathematical CalculationsGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Thai and Non-Thai Instructors' Perspectives On Peer Feedback Activities in English Oral PresentationsDocument22 pagesThai and Non-Thai Instructors' Perspectives On Peer Feedback Activities in English Oral PresentationsGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- The Relationship of Teaching Clarity and Student Academic Motivation in Online ClassesDocument9 pagesThe Relationship of Teaching Clarity and Student Academic Motivation in Online ClassesGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- ZARA Company Profile, Business Strategy, Leadership & Core CompetenciesDocument32 pagesZARA Company Profile, Business Strategy, Leadership & Core CompetenciesSano sandeep100% (1)

- Stephan Boehm, Christian Gehrke, Heinz D. Kurz, Richard Sturn - Is There Progress in Economics - Knowledge, Truth and The History of Economic Thought (2002, Edward Elgar Publishing) PDFDocument433 pagesStephan Boehm, Christian Gehrke, Heinz D. Kurz, Richard Sturn - Is There Progress in Economics - Knowledge, Truth and The History of Economic Thought (2002, Edward Elgar Publishing) PDFThiago FerreiraNo ratings yet

- MARKET STRUCTURES CROSSWORDDocument2 pagesMARKET STRUCTURES CROSSWORDSandy SaddlerNo ratings yet

- The Weekly Profile Guide - VolDocument19 pagesThe Weekly Profile Guide - VolJean TehNo ratings yet

- International Monetary SystemsDocument27 pagesInternational Monetary SystemsArun ChhikaraNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Post COVID-19 Pandemic on Inflation in MalaysiaDocument15 pagesThe Effects of Post COVID-19 Pandemic on Inflation in MalaysiaIyad AmeenNo ratings yet

- The RC ExcelDocument12 pagesThe RC ExcelGorang PatNo ratings yet

- Product Design and DevelopmentDocument14 pagesProduct Design and Developmentajay3480100% (1)

- Deloitte Essay Luke Oades First Draft LatestDocument5 pagesDeloitte Essay Luke Oades First Draft Latestapi-314109709No ratings yet

- Instructional Materials For Microeconomics: Polytechnic University of The PhilippinesDocument10 pagesInstructional Materials For Microeconomics: Polytechnic University of The PhilippinesIan Jowmariell GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Fin661 - Lesson Plan - March2021Document2 pagesFin661 - Lesson Plan - March2021MOHAMAD ZAIM BIN IBRAHIM MoeNo ratings yet

- Group Discussion Topics - Freshers, MBA, CAT, Interview EtcDocument5 pagesGroup Discussion Topics - Freshers, MBA, CAT, Interview EtcJc Duke M EliyasarNo ratings yet

- Rural Livelihood StrategiesDocument3 pagesRural Livelihood StrategiesDeoPudakaNo ratings yet

- Gross ProfitDocument3 pagesGross ProfitRafeh2No ratings yet

- SHS Q3 - Las Eval - Diss 11 W1 7Document39 pagesSHS Q3 - Las Eval - Diss 11 W1 7Gerard LacanlaleNo ratings yet

- QEP 2022 Theme General State TheIAShub Sample FIDocument26 pagesQEP 2022 Theme General State TheIAShub Sample FIakash bhattNo ratings yet

- Provide A Brief Overview of The Firms and Industry Sector. Rex Industry BerhadDocument4 pagesProvide A Brief Overview of The Firms and Industry Sector. Rex Industry Berhadainmazni5No ratings yet

- Discussion: Lesson 1. Emergence of The Social Science DisciplinesDocument8 pagesDiscussion: Lesson 1. Emergence of The Social Science Disciplinesrio mae carangaNo ratings yet

- Public Administration EbookDocument24 pagesPublic Administration Ebookapi-371002988% (17)

- Case Study On L.l.beanDocument11 pagesCase Study On L.l.beanMohit SharmaNo ratings yet

- William Cooper-Silent Weapons For Quiet WarsDocument28 pagesWilliam Cooper-Silent Weapons For Quiet WarsMihaita Rosca100% (2)

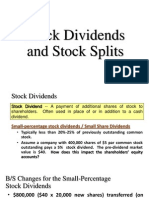

- Stock Dividends and Stock SplitsDocument18 pagesStock Dividends and Stock SplitsPaul Dexter Go100% (1)

- Cost Accounting Level 3: LCCI International QualificationsDocument14 pagesCost Accounting Level 3: LCCI International QualificationsHein Linn Kyaw80% (5)

- Cost of Capital Slides PDFDocument10 pagesCost of Capital Slides PDFBradNo ratings yet

- South Africa EconomyDocument11 pagesSouth Africa EconomyMohammed YunusNo ratings yet

- Contractual LaborDocument2 pagesContractual LaborArcillas Jess Niño100% (1)

- Vair ValueDocument15 pagesVair ValueyrperdanaNo ratings yet

- OSK Rubber Glove Industry in Malaysia ReportDocument8 pagesOSK Rubber Glove Industry in Malaysia ReportChoh Shee TeohNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Foreign Direct Investment On Ethiopian Economic GrowthDocument11 pagesThe Effect of Foreign Direct Investment On Ethiopian Economic GrowthWORKNEH GIRMANo ratings yet

- ECW1101 Week 1 Lecture - LDocument10 pagesECW1101 Week 1 Lecture - LMohammad RashmanNo ratings yet