Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Untitled

Uploaded by

Harathi VageeshanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Untitled

Uploaded by

Harathi VageeshanCopyright:

Available Formats

Tagores idea of nation as a cultural synthesis May 09, 2011 - Ananta Charan Sukla Tagores call for universalism

m as a cultural necessity was rather a psychological reflection of his attitude to the administrative policies of the British Raj. Tagore was dwindling in between conservatism and radicalism, the High Church and the Low Church, Brahminist principles and world views till the later days of hi s life when he adopted mostly the pleasure-loving lifestyle of his grandfather, abandoning the rigidity of his fathers ideology. But, all in all, he believed tha t Raja Rammohun Roys insight in reforming the Indian society must be worked out i n its completeness. Tagore writes: Our direct contact with the larger world of men was linked up with contemporary history of the English people whom we came to know in those earlie r days. It was mainly through their mighty literature that we formed our ideas w ith regard to these newcomers to our Indian shores. In those days, the type of l earning that was served out to us was neither plentiful nor diverse, now was the spirit of scientific inquiry very much in evidence. Thus, our scope being stric tly limited, the educated of those days had recourse to the English language and literature. Their days and nights were eloquent with the stately declamations o f Burke, with Macaulays long-rolling sentences; discussions centred upon Shakespe ares drama and Byrons poetry and above all upon the large-hearted liberalism of ni neteenth-century English politics. Thus, the Western educational system was consi dered the model one. But the English liberalism proved a treacherous disillusion and political mockery in the Indian context, a fact that Tagore very much experienced in the last year of his life, articulated in his essay, Crisis in Civilisation, where he express es his grievance against the English racism, contradictory to the spirit of huma nity revealed in the ideals of the English romantic poetry: The best and noblest gifts of humanity cannot be the monopoly of a particular race or country; its sc ope may not be limited nor may it be regarded as the misers hoard buried undergro und. That is why English literature, which nourished our minds in the past, does even now convey its deep resonance to our heart. Thus Tagores anti-racism and ant i-casteism in forming an ideal Indian society appear in his notion of nationalis m as a counter to its Western ideal. He insists that the Indian nation must embr ace a whole people. Tagore writes: What is the nation? It is the aspect of a whole people as an organised power the nation which is the organised self-interest of a whole people, when it is least human and least spiritual. One intimate experien ce of the nation is with the British nation. We have to reorganise that the hist ory of India does not belong to one particular race but to a process of creation to which various races of the world contributed the Dravidians and the Aryans, the ancient Greeks and the Persians, the Mohammedans of the West and those of Ce ntral Asia. Therefore, what I say about the nation has more to do with the histo ry of man, than specially with that of India. Tagores concept of the whole people that constitute the nation is not merely territ orial and ethnic. It is an organic unification of several social practices such as language, religion and manners, a unification which is perhaps most spectacul ar in case of the Indian subcontinent that emerged politically and economically during the British rule. Tagore further writes: A nation, in the sense of the pol itical and economic union of a people, is that aspect which a whole population a ssumes when organised for a mechanical purpose. It is an end in itself. It is a spontaneous self-expression of a man as a social being. It is a natural regulati on of human relationships, so that man can develop ideals of life in cooperation with one another. It has also a political side, but this is only for a special purpose. It is for self-preservation. It is merely the side of power, not of human ideals. Thus, th e nation in its social perspective is a healthy concept with its humanist or rom antic connotation whereas it is a disease in its political context a threat for the whole humanity in its connotation of nationalism as exemplified by the Nazi consciousness and more evident in the British colonial slogan Rule Britania Rule the Waves. Therefore, Tagore declares, Nationalism is a great menace.

Division of Bengal was in particular a great shock to Tagore. He, therefore, acc uses the British rulers in India of a severe self-contradiction. That which was t ruly best in their own civilisation, the upholding of the dignity of human relat ionship, has no place in the British administration of this country. He, therefor e, does not even hesitate to provoke violence for and inflict personal injury to the members of the ruling race: In India, so long as no personal injury is inflict ed upon any member of the ruling race, this barbarism seems assured of perpetuit y, making us ashamed that we have to live under such an administration. Subsequently, he pities the fall of the English liberalism and generosity manife st in their literary tradition that triggered his imagination one day: We also no ted with admiration how a band of valiant Englishmen laid down their lives in Sp ain for the Republican cause. Even though the English had not aroused themselves sufficiently to their sense of responsibility towards China in the far East in their own immediate neighbourhood, they did not hesitate to sacrifice themselves to the cause of freedom. Such acts of heroism reminded me once of the true Engl ish spirit to which in my early days I had given my full quota of faith and admi ration, and made me wonder how imperialist greed could bring about so ugly a tra nsformation in the character of so great a nation. Tagores call for universalism as a cultural necessity was rather a psychological reflection of his attitude to the administrative policies of the British Raj tha t involved necessarily indeed an element of cultural diversity the superiority o f the dominant colonisers over the dominated colonised. The mystery of universal ism expresses itself in both contra and pro-imperialism, a reaction of the domin ated in its urge to be one with the dominant. Stephen Howe in his book Oxford Very Short Introduction to Empire thus articulat es this aspect of the colonial rule in its imperial justification of the cultura l diversity: It often rested on, and its rulers sometimes justified themselves by reference to deep cultural divisions and inequalities. But at the same time, the inevitable production of this cultural division was a cultural hybridity many k inds of cultural interchange that became exceedingly fashionable for the dominat ed. In fact, this cultural hybridity, the most important continuing legacy of th e colonial rule, prompted both Tagore and his preceptor Rammohun Roy for shaping a society, a Samaj, on the foundation of cultural universalism. Tagore writes: All elements in our won culture have to be strengthened; not to re sist the culture of the West, but to accept and assimilate it. At our centre of Indian learning we must provide for the coordinated study of all the different c ultures that have either arisen here or come here, so that we might create a new synthesis as splendid as the old. This psychological factor underpins Tagores notion of a whole people that constitut es or should constitute a nation, particularly the emerging post-colonial Indian nation. The so-called Eastern view of nation attributed to Tagore is radically an hybrid of both the Eastern and Western cultural synthesis. A notion of nation founded on the elements of territory, race, language and religion is discarded. And ambivalently, this is the meeting point as well as the parting point for Gan dhi and Tagore. While agreeing on the point of the cultural synthesis, the forme r insisted on putting up conservative side of the Indian culture rather than ref orming all the traditional aspects of the cultural values of India, so as to ide ntify it as the Indian, rejecting Tagores call for a total synthesis a new Indian nation above all differences. Such a view seems to be the expression of a shock, so to say, that he received for the dual character of the British people which h e accepted as the ideal one for their literature and philosophy, but disappointe d later by their treachery. Dwindling in between the two he was unable to reject the Western values altogeth er, nor could he assimilate them as they are. This middle path of the Buddhist w orld view once again took over Tagore in envisaging a whole people. In such a formulation what was functioning more powerfully was not any philosoph ical exercise, but the marked emotionalism that defines Tagores Romantic imaginat ion as a poet in him obviously the poet was dominating rather than a philosopher .

The author is a former professor of English, Sambalpur University, and an eminen t philosopher of art, religion and language. He is the founder editor of the Jou rnal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics. http://www.asianage.com/ideas/tagore-s-idea-nation-cultural-synthesis-848

You might also like

- Hague Peace 1899 1907Document3 pagesHague Peace 1899 1907Harathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Aadhaar: Dynamics of India's Digital Identity RevolutionDocument17 pagesAadhaar: Dynamics of India's Digital Identity RevolutionHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

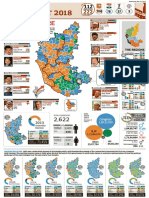

- VERDICT 2018: The Big PictureDocument1 pageVERDICT 2018: The Big PictureHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Elimination of All Forms of Religious IntoleranceDocument4 pagesElimination of All Forms of Religious IntoleranceHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- An Insiders Story of Muslim Life in Old CityDocument185 pagesAn Insiders Story of Muslim Life in Old CityHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- India and Its Television Ownership DemocDocument14 pagesIndia and Its Television Ownership DemocHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- 2008 Himsavirodh JudgemetDocument14 pages2008 Himsavirodh JudgemetHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Satyam Scam JudgementDocument971 pagesSatyam Scam JudgementSampath Bulusu100% (5)

- (Great Books in Philosophy) John Dewey-Individualism Old and New-Prometheus Books (1999) PDFDocument69 pages(Great Books in Philosophy) John Dewey-Individualism Old and New-Prometheus Books (1999) PDFHarathi Vageeshan100% (4)

- An Old Book On Sanatana DharmaDocument426 pagesAn Old Book On Sanatana DharmaH Janardan PrabhuNo ratings yet

- Telugu Costal Andhra Novel - Naresh - VividhaDocument1 pageTelugu Costal Andhra Novel - Naresh - Vividhanaresh_nunnaNo ratings yet

- Profile MNRoyDocument21 pagesProfile MNRoyHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- COncept of Citizenship and RightsDocument72 pagesCOncept of Citizenship and RightsHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Viphalandhraprdesh With CoverDocument102 pagesViphalandhraprdesh With CoverHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- A Rebuttal To VisalandhraDocument113 pagesA Rebuttal To VisalandhraHarathi Vageeshan100% (1)

- Letter To Sri ChandrashekharDocument1 pageLetter To Sri ChandrashekharHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Paper On Telngana PoliticsDocument6 pagesPaper On Telngana PoliticsHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- From The IrawadyDocument3 pagesFrom The IrawadyHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Letter To Friends With Annexures EnglishDocument6 pagesLetter To Friends With Annexures EnglishHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Acadmic ImperialismDocument1 pageAcadmic ImperialismHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- D D Kosambi: The Scholar and His Intellectual PursuitsDocument24 pagesD D Kosambi: The Scholar and His Intellectual PursuitsHarathi Vageeshan100% (1)

- Noam Chomsky The Propaganda SystemDocument3 pagesNoam Chomsky The Propaganda SystemHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Another Comprehensive AppealDocument5 pagesAnother Comprehensive AppealHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- LobbbyingDocument2 pagesLobbbyingHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Agro Climatic Zones in IndaDocument21 pagesAgro Climatic Zones in IndaHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- Agro Climatic Regions in India - BroadDocument1 pageAgro Climatic Regions in India - BroadHarathi VageeshanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)