Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Collins - Guest Editorial What Democracy Looks Like (2011)

Uploaded by

prakirati7531Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Collins - Guest Editorial What Democracy Looks Like (2011)

Uploaded by

prakirati7531Copyright:

Available Formats

Dialect Anthropol (2011) 35:131133 DOI 10.

1007/s10624-011-9233-y

Guest editorial: What democracy looks like

Jane L. Collins

Published online: 9 June 2011 Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011

Greetings from Wisconsin, 3 months into what some have tagged our Main Street Rebellion. A couple of weeks ago, I found myself sitting in a messy, airless room above a coffee shop, poring over Republican-led petitions to recall Democratic senators. We were perusing the handiwork of out-of-state canvassers who had entered long lists of names from the phone book, including an entry for State Assembly Representative Mark Pocans father, who has been dead for 20 years. Other volunteers were out in the streets collecting afdavits from people who had signed the petitions because they were told they demanded the recall of Governor Scott Walker. Republicans were contesting the validity of six recall petitions led by Democrats against Republican senatorson the grounds that the petitioners names were not included on all pages of the document. Three blocks away from the coffee shop ofce, teams of citizen observers watched the recount of ballots from the recent State Supreme Court election. Looking up from a pile of petitions, a fellow volunteer plaintively turned the movements pervasive tag-line into a question: This is what democracy looks like? How did we get to this point? And what does it say about the prospects for grassroots movements targeting corporate power and defending labor rights and social spending? These are questions I have been asking myself incessantly since February. Here is an attempt to recap the, How did we get here question. In February and March of this year, public sector workers and their friends and neighbors took to the streets in Wisconsin. A few months earlier, perhaps in a t of pique at the bad news of the recession, our state had elected a Republican governor and Republican majorities in both legislative houses. The governor, Scott Walker, had campaigned as a moderate but soon revealed himself to be at the cutting edge of the Tea Party agenda. The massive demonstrations that began February 14th were

J. L. Collins (&) Department of Community & Environmental Sociology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA e-mail: jcollins@ssc.wisc.edu

123

132

J. L. Collins

ignited by the unveiling of a malicious Budget Repair Bill that stripped collective bargaining rights from public sector employees, home health aides, and daycare workers, while imposing new rules on public sector unions that will make it impossible for them to survive. (Similar bills have now been introduced or passed in at least 12 other states). In the months that followed, the governor released a harsh and socially regressive budget while our legislature churned out a steady stream of laws and policies that concentrated power in the governors hands, dismantled regulations across the economy, gave Wisconsin the most restrictive voting laws in the country, and brutally cut social programsfrom recycling and public transportation to medical assistance and schools. In response to this aggressive right-wing agenda, beginning on February 15th, teachers across the state called in sick and protesters began showing up at the Capitolinitially 10,000 of them, then 20,000, building to 70,000 on February 19 and 150,000 on March 12th. Despite the snow and intense cold, a broad swath of the community came out to support public workers, including police ofcers and reghters, teamsters and steelworkers, immigrant workers, and faith communities. With protesters chanting, this is what democracy looks like, and, Recall Walker, accompanied by bagpipes and cowbells, earnest signs and street theater, the Capitol square became a fragile but intense political eld. The presence of people in the Capitol seeking to testify before the legislatures Joint Finance Committee evolved into a kind of friendly occupation as the University of Wisconsins Teaching Assistants Association organized the protesters care and feeding. Thousands chanted and drummed, sang and gave speeches through daylight hours and reghters and steelworkers, teachers and students slept next to each other on the Capitol oor at night. Bob Lafollettes statue became a kind of shrine. This is the part of the story that captured the public imaginationthe narrative of working classes (in the medias parlance Main Street) nding their voice and speaking back to austerity politics; the images of stalwart Midwestern families standing in the snow. The mainstream media gave some coverage to the protests (Fox slipped in some footage of violent altercationswith palm trees in the background giving away the fact that they were not lmed in Madison). A blogger impersonating David Kocha billionaire rightist Republican contributormade a phone call to our governor that revealed how profoundly his agenda was shaped by interests outside the state. But the struggle could not stay in the streets forever. Even as the weather warmed, the momentum shifted to crucial but less photogenic contexts: the courts, the spring elections for a new state Supreme Court Justice, recall campaigns and the battle over the budget. Walker succeeded in clearing protesters from the Capitol (the Madison, Dane County, and Capitol police departments refused to remove them, so the governor called in the State Highway Patrol. Now, for the rst time in state history, people must pass through a metal detector and police inspection to enter the Capitol). The legislature passed the hated budget repair bill on the night of March 9th, without proper notice, leading to court challenges that still have not been resolved. What do these unfolding events tell us about the prospects for an ongoing grassroots movement? The protests in Wisconsin owed a great deal to the theoretical and strategic groundwork laid by community-based labor movements in the global South and imported into the United States by immigrant workers in unions like the

123

Guest editorial: What democracy looks like

133

SEIU and UNITE/HERE, as well as to the global justice movements innovations in organizing loose networks of protesters around specic projects without a single leader. Wisconsin has the kind of civic infrastructure that could put people in the streets (the South-Central Federation of Labor, which brings together the regions unions; the 50 year old School for Workers; the Center on Wisconsin Strategy; the Interfaith Coalition for Worker Justice; and the Teaching Assistants Association to name a few groups and organizations). As the momentum shifted from the Capitol square to the more mundane tasks of mounting the recall campaigns, there has been a tendency for people to work more and more through their unions, or the Democratic Partys grassroots groups. Some wholly new organizations have formed to foster cross-fertilization and collaboration in pursuit of particular goals, for example, publication of an alternative peoples budget. But the question of what the long-term movement is going to look like is still up in the air. One of the most unanticipated aspects of the movement to date is its broad basethe way that an attack on the public sector has reverberated throughnot just all the unions in the statebut the states working classes. Entire communities are pulling together, both to protect what they understand to be the economys last good jobs and also to protect the services that those public workers provide to the community. The outpouring of anger in response to the right-wing onslaught of the last months and the sustained, but less glamorous, efforts to turn things around that are still underway, took all of us by surprise. Like recent uprisings in Cairo and Tunisia, the movement that has emerged in Wisconsin has labor at it is center, but it is not a labor movement. What is happening in Wisconsin is in many ways an anti-corporate struggle. It responds to a corporate power grab that was made possible by the US Supreme Courts Citizens United decision in 2010, which gave corporations virtually unlimited power to nance electoral campaigns. This new corporate clout tipped the scales in the fall 2010 gubernatorial and state-level elections around the country as well as in races for the US House of Representatives. As newly elected governors set about doing the bidding of their corporate donors, they unleashed a backlash from the populace. That backlash joins workers who will lose rights with the elderly, the disabled, farmers, and the poor, all of whom will lose state medical assistance, and with the unemployed and working poor who will lose access to many other forms of state support. It mobilizes vast numbers of people ghting what David Harvey calls, accumulation by dispossession (although they do not know it by that name). These are people who believe that certain services (roads, re and police protection, garbage collection, schools, and public transportation) are best provided for collectively and who do not want to lose them or see them privatized. This reclaiming of civic space, labor rights, and collective investments is not conned to Wisconsin, but is unfolding today in almost every state in the United States. While the popular movements in the Middle East and North Africa in 2011 challenge distinct congurations of power (distinct from those in the US context and distinct from each other), I believe that the rights, civic space, and collective goods they seek to reclaim are in many ways the same. All of us face the challenge of channeling the outrage (and public playfulness) of street protests into the kind of longrange strategies that can derail the agendas of despotic actors and reclaim power for popular classes.

123

You might also like

- Wisconsin ProtestsDocument11 pagesWisconsin ProtestsalpslnaydnNo ratings yet

- Divided Unions: The Wagner Act, Federalism, and Organized LaborFrom EverandDivided Unions: The Wagner Act, Federalism, and Organized LaborNo ratings yet

- The Triumph of Occupy Wall StreetDocument4 pagesThe Triumph of Occupy Wall Streetelyas bergerNo ratings yet

- It Started in Wisconsin: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the New Labor ProtestFrom EverandIt Started in Wisconsin: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the New Labor ProtestRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Cliff NotesDocument13 pagesCliff Notesanon-91129100% (3)

- Democracy’s Capital: Black Political Power in Washington, D.C., 1960s–1970sFrom EverandDemocracy’s Capital: Black Political Power in Washington, D.C., 1960s–1970sNo ratings yet

- D.C. Mic Check: Volume 2, Issue 2Document8 pagesD.C. Mic Check: Volume 2, Issue 2D.C. Mic CheckNo ratings yet

- Politics of Empowerment: Disability Rights and the Cycle of American Policy ReformFrom EverandPolitics of Empowerment: Disability Rights and the Cycle of American Policy ReformNo ratings yet

- Workers Vanguard No 753 - 02 March 2001Document12 pagesWorkers Vanguard No 753 - 02 March 2001Workers VanguardNo ratings yet

- When the Smoke Cleared: The 1968 Rebellions and the Unfinished Battle for Civil Rights in the Nation’s CapitalFrom EverandWhen the Smoke Cleared: The 1968 Rebellions and the Unfinished Battle for Civil Rights in the Nation’s CapitalNo ratings yet

- Spring EssayDocument2 pagesSpring Essaydavidgcharles05No ratings yet

- Rallying for Immigrant Rights: The Fight for Inclusion in 21st Century AmericaFrom EverandRallying for Immigrant Rights: The Fight for Inclusion in 21st Century AmericaNo ratings yet

- Occupy Wall Street Movement Research PaperDocument9 pagesOccupy Wall Street Movement Research Paperafnhgssontbxkd100% (1)

- March On Washington PrefaceDocument13 pagesMarch On Washington PrefaceRenee FeltzNo ratings yet

- In the City of Neighborhoods: <I>Seattle's History of Community Activism <Br>And Non-Profit Survival Guide</I>From EverandIn the City of Neighborhoods: <I>Seattle's History of Community Activism <Br>And Non-Profit Survival Guide</I>No ratings yet

- JFK, Freedom Riders, and The Civil Rights Movement: Lesson PlanDocument19 pagesJFK, Freedom Riders, and The Civil Rights Movement: Lesson Planapi-555141741No ratings yet

- Southern California Metropolis: A Study in Development of Government for a Metropolitan AreaFrom EverandSouthern California Metropolis: A Study in Development of Government for a Metropolitan AreaNo ratings yet

- Ranking The Mayoral Candidates - PensionsDocument1 pageRanking The Mayoral Candidates - PensionssaywhatuserNo ratings yet

- "A War Within Our Own Boundaries" - Lyndon Johnson's Great Society and The Rise of The Carceral StateDocument13 pages"A War Within Our Own Boundaries" - Lyndon Johnson's Great Society and The Rise of The Carceral StatePalvasha KhanNo ratings yet

- The Right Talk: How Conservatives Transformed the Great Society into the Economic SocietyFrom EverandThe Right Talk: How Conservatives Transformed the Great Society into the Economic SocietyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Downing, Karley - GOV: Sent: SubjectDocument120 pagesDowning, Karley - GOV: Sent: SubjectWisconsinOpenRecordsNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Right to Work: Antilabor Democracy in Nineteenth-Century ChicagoFrom EverandThe Origins of Right to Work: Antilabor Democracy in Nineteenth-Century ChicagoNo ratings yet

- Tenets of Reforms Introduced During The Progressive EraDocument6 pagesTenets of Reforms Introduced During The Progressive EraNEETI GUPTA 220517No ratings yet

- 1963 March On Washington FINAL PLANSDocument12 pages1963 March On Washington FINAL PLANShbiandudiNo ratings yet

- Countermobilization: Policy Feedback and Backlash in a Polarized AgeFrom EverandCountermobilization: Policy Feedback and Backlash in a Polarized AgeNo ratings yet

- Chap.9 ShepsleDocument44 pagesChap.9 ShepsleHugo MüllerNo ratings yet

- America Beyond Capitalism: Reclaiming our Wealth, Our Liberty, and Our DemocracyFrom EverandAmerica Beyond Capitalism: Reclaiming our Wealth, Our Liberty, and Our DemocracyRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (12)

- Eleven Days in October 2019 The Indigenous Movement in The Recent Mobilizations in EcuadorDocument8 pagesEleven Days in October 2019 The Indigenous Movement in The Recent Mobilizations in EcuadorJoshua Montaño ParedesNo ratings yet

- Presente!: Latin@ Immigrant Voices in the Struggle for Racial Justice / Voces Inmigranted Latin@s en la Lucha por la Justicia RacialFrom EverandPresente!: Latin@ Immigrant Voices in the Struggle for Racial Justice / Voces Inmigranted Latin@s en la Lucha por la Justicia RacialNo ratings yet

- SolidarityZinefinal BookletDocument8 pagesSolidarityZinefinal BookletWinston Pennington-FlaxNo ratings yet

- Introduction of Friends, Followers and The FutureDocument16 pagesIntroduction of Friends, Followers and The FutureCity LightsNo ratings yet

- Takeover: How the Left's Quest for Social Justice Corrupted LiberalismFrom EverandTakeover: How the Left's Quest for Social Justice Corrupted LiberalismNo ratings yet

- OWS and The Hard Tasks AheadDocument8 pagesOWS and The Hard Tasks AheadChristopher CarricoNo ratings yet

- Fragile Democracy: The Struggle over Race and Voting Rights in North CarolinaFrom EverandFragile Democracy: The Struggle over Race and Voting Rights in North CarolinaNo ratings yet

- Final Paper For American DemocracyDocument6 pagesFinal Paper For American Democracyapi-549559353No ratings yet

- Organizing for Power: Building a 21st Century Labor Movement in BostonFrom EverandOrganizing for Power: Building a 21st Century Labor Movement in BostonNo ratings yet

- Capitulo 1 SellersDocument20 pagesCapitulo 1 SellersLaura Garcia RincónNo ratings yet

- The Great Tea Party in the Old Northwest: State Constitutional Conventions, 1847-1851From EverandThe Great Tea Party in the Old Northwest: State Constitutional Conventions, 1847-1851No ratings yet

- Occupy Wall StreetDocument6 pagesOccupy Wall StreetHassan Mohammad RafiNo ratings yet

- The Impeachment of President Andrew Johnson – History Of The First Attempt to Impeach the President of The United States & The Trial that Followed: Actions of the House of Representatives & Trial by the Senate for High Crimes and Misdemeanors in OfficeFrom EverandThe Impeachment of President Andrew Johnson – History Of The First Attempt to Impeach the President of The United States & The Trial that Followed: Actions of the House of Representatives & Trial by the Senate for High Crimes and Misdemeanors in OfficeNo ratings yet

- Occupied Wisconsin State Journal IIIDocument5 pagesOccupied Wisconsin State Journal IIIOccupiedWiscSJNo ratings yet

- The Walls Within: The Politics of Immigration in Modern AmericaFrom EverandThe Walls Within: The Politics of Immigration in Modern AmericaNo ratings yet

- The Progressive Tradition in American PoliticsDocument31 pagesThe Progressive Tradition in American PoliticsCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Conservatives and RaceDocument18 pagesConservatives and RaceNPINo ratings yet

- Excerpt For Who Stole The American Dream? by Hedrick SmithDocument6 pagesExcerpt For Who Stole The American Dream? by Hedrick SmithSouthern California Public RadioNo ratings yet

- AP US History NotecardsDocument5 pagesAP US History NotecardsLauren GreinerNo ratings yet

- The Two-Party System in The United StatesDocument19 pagesThe Two-Party System in The United StatesAnonymous Jdv1O1No ratings yet

- Kevin Howley On RadioDocument20 pagesKevin Howley On RadioJesse WalkerNo ratings yet

- The Left's New MachineDocument11 pagesThe Left's New MachinenoahflowerNo ratings yet

- Digital: MagazineDocument49 pagesDigital: Magazinemichen077No ratings yet

- The Progressive EraDocument4 pagesThe Progressive EraLinda PetrikovičováNo ratings yet

- February 2012, Volume 1, Issue 3Document4 pagesFebruary 2012, Volume 1, Issue 3occupyhelenaNo ratings yet

- The Future of Us Civil SocietyDocument5 pagesThe Future of Us Civil SocietyStephanie Gómez ZafraNo ratings yet

- Protest UpdateDocument3 pagesProtest UpdateNFIFWINo ratings yet

- A Short, Personal History of The Global Justice MovementDocument12 pagesA Short, Personal History of The Global Justice MovementMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Eisenstadt - Multiple Modernities (2000)Document29 pagesEisenstadt - Multiple Modernities (2000)prakirati7531No ratings yet

- Ammar - A History of Rice Policies in ThailandDocument18 pagesAmmar - A History of Rice Policies in Thailandprakirati7531No ratings yet

- Jackson - Political Economy of 21st Century Thai SupernaturalismDocument12 pagesJackson - Political Economy of 21st Century Thai Supernaturalismprakirati7531No ratings yet

- George Bond - The Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response (1988)Document166 pagesGeorge Bond - The Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response (1988)prakirati7531No ratings yet

- Hallisey - Roads Taken and Not Taken in The Study of Theravada Buddhism (1995)Document16 pagesHallisey - Roads Taken and Not Taken in The Study of Theravada Buddhism (1995)prakirati7531100% (1)

- Hart - Marcel Mauss in Pursuit of The Whole (2007)Document13 pagesHart - Marcel Mauss in Pursuit of The Whole (2007)prakirati7531No ratings yet

- Engelke - Religion & The Media Turn (2010)Document9 pagesEngelke - Religion & The Media Turn (2010)prakirati7531No ratings yet

- Hart - Marcel Mauss in Pursuit of The Whole (2007)Document13 pagesHart - Marcel Mauss in Pursuit of The Whole (2007)prakirati7531No ratings yet

- Bell Ritual Perspectives and Dimensions Revised EditionDocument368 pagesBell Ritual Perspectives and Dimensions Revised EditionTóth Krisztián100% (9)

- Braun - Review Article Meditating On Legitimacy & Power in Burma (2012)Document4 pagesBraun - Review Article Meditating On Legitimacy & Power in Burma (2012)prakirati7531No ratings yet

- (S. J. Tambiah) World Conqueror and World RenounceDocument566 pages(S. J. Tambiah) World Conqueror and World RenounceLuciana FerreiraNo ratings yet

- (Michael Banton) Anthropological Approaches To TheDocument148 pages(Michael Banton) Anthropological Approaches To TheAlberto Fidalgo CastroNo ratings yet

- Keane - Religious Language (1997)Document26 pagesKeane - Religious Language (1997)prakirati7531No ratings yet

- Assessment: Bipolar DisorderDocument2 pagesAssessment: Bipolar DisorderMirjana StevanovicNo ratings yet

- Bluetooth Modules - Martyn Currey PDFDocument64 pagesBluetooth Modules - Martyn Currey PDFAng Tze Wern100% (1)

- Dislocating The Sign: Toward A Translocal Feminist Politics of TranslationDocument8 pagesDislocating The Sign: Toward A Translocal Feminist Politics of TranslationArlene RicoldiNo ratings yet

- Theory of Karma ExplainedDocument42 pagesTheory of Karma ExplainedAKASH100% (1)

- FeistGorman - 1998-Psychology of Science-Integration of A Nascent Discipline - 2Document45 pagesFeistGorman - 1998-Psychology of Science-Integration of A Nascent Discipline - 2Josué SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Flotect Vane Operated Flow Switch: Magnetic Linkage, UL ApprovedDocument1 pageFlotect Vane Operated Flow Switch: Magnetic Linkage, UL ApprovedLuis GonzálezNo ratings yet

- International Waiver Attestation FormDocument1 pageInternational Waiver Attestation FormJiabao ZhengNo ratings yet

- Hempel's Curing Agent 95040 PDFDocument12 pagesHempel's Curing Agent 95040 PDFeternalkhut0% (1)

- Fluid MechanicsDocument46 pagesFluid MechanicsEr Suraj Hulke100% (1)

- David Freemantle - What Customers Like About You - Adding Emotional Value For Service Excellence and Competitive Advantage-Nicholas Brealey Publishing (1999)Document312 pagesDavid Freemantle - What Customers Like About You - Adding Emotional Value For Service Excellence and Competitive Advantage-Nicholas Brealey Publishing (1999)Hillary Pimentel LimaNo ratings yet

- Chrome Blue OTRFDocument4 pagesChrome Blue OTRFHarsh KushwahaNo ratings yet

- Summer Training Report at Bikanervala FoodsDocument21 pagesSummer Training Report at Bikanervala FoodsVanshika Srivastava 17IFT017100% (1)

- Ramesh Dargond Shine Commerce Classes NotesDocument11 pagesRamesh Dargond Shine Commerce Classes NotesRajath KumarNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3-WEF-Global Competitive IndexDocument3 pagesAssignment 3-WEF-Global Competitive IndexNauman MalikNo ratings yet

- Talking About Your Home, Furniture and Your Personal Belongings - Third TemDocument4 pagesTalking About Your Home, Furniture and Your Personal Belongings - Third TemTony Cañate100% (1)

- People V Gona Phil 54 Phil 605Document1 pagePeople V Gona Phil 54 Phil 605Carly GraceNo ratings yet

- Direct InstructionDocument1 pageDirect Instructionapi-189549713No ratings yet

- Vol 98364Document397 pagesVol 98364spiveynolaNo ratings yet

- Preterite vs Imperfect in SpanishDocument16 pagesPreterite vs Imperfect in SpanishOsa NilefunNo ratings yet

- OF Ministry Road Transport Highways (Road Safety Cell) : TH THDocument3 pagesOF Ministry Road Transport Highways (Road Safety Cell) : TH THAryann Gupta100% (1)

- Managerial Accounting 12th Edition Warren Test Bank DownloadDocument98 pagesManagerial Accounting 12th Edition Warren Test Bank DownloadRose Speers100% (21)

- IAS Exam Optional Books on Philosophy Subject SectionsDocument4 pagesIAS Exam Optional Books on Philosophy Subject SectionsDeepak SharmaNo ratings yet

- School Communication Flow ChartsDocument7 pagesSchool Communication Flow ChartsSarah Jane Lagura ReleNo ratings yet

- PSE Inc. V CA G.R. No. 125469, Oct 27, 1997Document7 pagesPSE Inc. V CA G.R. No. 125469, Oct 27, 1997mae ann rodolfoNo ratings yet

- Compatibility Testing: Week 5Document33 pagesCompatibility Testing: Week 5Bridgette100% (1)

- Ds B2B Data Trans 7027Document4 pagesDs B2B Data Trans 7027Shipra SriNo ratings yet

- Siege by Roxane Orgill Chapter SamplerDocument28 pagesSiege by Roxane Orgill Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressNo ratings yet

- 8086 ProgramsDocument61 pages8086 ProgramsBmanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Intro - LatinDocument11 pagesLesson 1 Intro - LatinJohnny NguyenNo ratings yet

- Life Stories and Travel UnitDocument3 pagesLife Stories and Travel UnitSamuel MatsinheNo ratings yet

- We've Got Issues: How You Can Stand Strong for America's Soul and SanityFrom EverandWe've Got Issues: How You Can Stand Strong for America's Soul and SanityNo ratings yet

- The Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteFrom EverandThe Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (16)

- The Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpFrom EverandThe Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Nine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesFrom EverandNine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesNo ratings yet

- Game Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeFrom EverandGame Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (572)

- The Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalNo ratings yet

- Thomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaFrom EverandThomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (107)

- Modern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesFrom EverandModern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushFrom EverandThe Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismFrom EverandReading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismNo ratings yet

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonFrom EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- The Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political TribalismFrom EverandThe Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political TribalismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- Commander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943From EverandCommander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

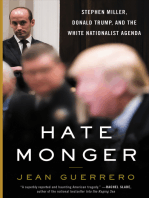

- Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist AgendaFrom EverandHatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist AgendaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Witch Hunt: The Story of the Greatest Mass Delusion in American Political HistoryFrom EverandWitch Hunt: The Story of the Greatest Mass Delusion in American Political HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Blood Money: Why the Powerful Turn a Blind Eye While China Kills AmericansFrom EverandBlood Money: Why the Powerful Turn a Blind Eye While China Kills AmericansRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- The Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorFrom EverandThe Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorNo ratings yet

- The Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldFrom EverandThe Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- The Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaFrom EverandThe Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Power Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicFrom EverandPower Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicNo ratings yet

- An Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. FordFrom EverandAn Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. FordRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Trumpocracy: The Corruption of the American RepublicFrom EverandTrumpocracy: The Corruption of the American RepublicRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (68)

- The Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. BushFrom EverandThe Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Confidence Men: Wall Street, Washington, and the Education of a PresidentFrom EverandConfidence Men: Wall Street, Washington, and the Education of a PresidentRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (52)