Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Perverse Trade Offs: Ethical Considerations in Sustainable Development

Uploaded by

Eric Britton (World Streets)Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Perverse Trade Offs: Ethical Considerations in Sustainable Development

Uploaded by

Eric Britton (World Streets)Copyright:

Available Formats

EnvironmEntal lEadErship

Perverse Trade-offs

In their 2001 book Perverse Subsidies, Norman Myers and Jennifer Kent laid out in exacting detail how governments around the world support economic and environmental policies that have the exact opposite effect from their stated objectives of improving the economy and the environment.1 For example, subsidies for corn-based ethanol fuels in the United States have impacted food prices around the world. Moreover, the energy balance from using ethanol based on corn is actually so close that several factors can easily change whether ethanol ends up a net energy winner or loser.2 Life-cycle analyses for cornbased ethanol depend on a number of underlying assumptionsand the initial assumptions that brought subsidies and positive media coverage were far from realistic. as each stakeholder adds their spin to the mix. In democracies, there are protocols (such as notices of proposed rulemaking) that are designed to bring fairness and balance to the process. The system is far from perfect, but it is the best that civil society has to offer.

Ethical considerations in

sustainable development

Corporate Decision Making

But what about the decision-making processes at corporations? Within business organizations, decisions that have far-reaching health, safety, environmental, and economic impacts on entire communities (if not nations) can be made unilaterally, sometimes literally by one individual. Corporate managers are in the business of making trade-offsweighing one choice against another. But can those trade-off decisions become so faulty as to be perverse? In this context, we define perverse to mean morally and ethically reprehensible. Dozens of high-visibility disasters caused by business activities provide ample evidence that corporate decision makers can become corrupted and unethical.

The Public Policy Process

Economic and environmental policies are established by processes that vary in transparency and inclusivity. Big money is at stake. There can be winners and losers, which motivates stakeholders to gear up their influence machinery. Some agendas are obvious, while others are hidden. A skeptic observing the process might conclude that Figures do not lie, but liars figure,

Richard MacLean and Kimberly Abeel

2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/tqem.20294

Environmental Quality Management / DOI 10.1002/tqem / Spring 2011 / 103

This column explores the business decisionmaking process relative to sustainable development. What are the internal mechanisms that ensure ethical decisions? Clearly, some companies are extremely good at making ethical judgments. Others have disastrous track recordsan indicator that their trade-offs process had reached the perverse level.

Do Regulations Define Right and Wrong?

The most common question that managers ask before making any business decision is Is it legal? For the vast majority of decisions, the answer to this question can provide reassurance and protection against future lawsuits (or even imprisonment). Companies avidly Companies find it notoriously explore legal loopdifficult to make decisions that holes. Indeed, some involve environment, health, and have touted their abilsafety. ity to seek competitive advantage by being clever at such practices. When organizations become too aggressive in this respect, the result can be financially devastating. Creative accounting practices and scandals have brought down or greatly diminished the brand of companies such as WorldCom, Enron, Tyco International, Qwest Communications, Lehman Brothers, and many others. But at least the damage from financial and accounting decisions is largely limited to the economic sphere. Yes, individuals, employees, shareholders, and possibly communities suffer monetary loss. But they do not literally suffer direct loss of life.

much more seriousand often irreversible. The damage resulting from unprincipled corporate decisions may extend over generations. It can injure innocent parties who may have a direct stake in the outcome but no control over the decision. It can have a disproportionate impact on vulnerable individuals who are more at risk than the general population. It can include intangibles, such as access to natural beauty. Companies find it notoriously difficult to make decisions that involve environment, health, and safety. The issues may be abstract, they may cover uncharted territory, and they may have no precedent. The business decisions often require nuanced judgment calls. Moreover, the consequences of a bad EHS decision may not become apparent for decades. Hence, the issue on which a decision must be made may not even be covered by applicable laws and regulations. By definition, regulations represent closing the barn door on problems that already have been relatively well defined.

Crossing the Line

Reducing the decision-making process to a binary yes/no choice that hinges on legality clearly is not wise. But companies and trade associations sometimes go even further: They cross the line to perverse conduct by influencing the rule-making process itself with tactics intended to delay or neuter regulations. Or they seek to obfuscate public awareness of dangers. One obvious example here is the tobacco industry, which spent large sums on advertising and pseudoscientific research supporting its position on the safety of smoking.

Regulatory Capture and Its Consequences Making Decisions When Environment, Health, and Safety Are at Stake

When decisions involve environmental, health, and safety (EHS) issues, the losses can be Industries clearly seek to influence the regulatory agencies that govern them, and their influence has grown in power. Some charge that trade organizations are engaged in regulatory capture of

104 / Spring 2011 / Environmental Quality Management / DOI 10.1002/tqem

Richard MacLean and Kimberly Abeel

agencies charged with protecting the public interestand that industry consultants are defining science and reviewing each others work for profit.3 Numerous instances can be cited where industry has delayed the promulgation of regulations. For example, the dangers of asbestos, chlorofluorocarbons, and lead in gasoline, and the link between aspirin and an increased risk of Reyes syndrome in children, were all well established years (if not decades) before regulations were adopted or warnings required. In the United States, industry has pressured government agencies to produce increased documentation and meet industrys definition of sound science before moving forward with regulations. These demands have created what many believe to be unreasonable standards of evidence that interfere with agencies ability to regulate. For example, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) initiated its first risk assessment of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the 1970s. Yet the debate on PCBs and the regulatory challengescontinue to this day. So entangled is the regulatory process in the United States that US-based multinationals look to Europe for guidance in determining the acceptability of certain practices.

With most business decisions, the costs and benefits of the various options are relatively easy to define. When there are risks, they tend to be associated with factors such as changing economic conditions, customer acceptance of a new product or service, and uncertainties in the regulatory environment. This is Management 101, supported by models such as Porters five forces.4

Making the Business Case for Sustainability

For decades, environmental professionals have attempted to influence the corporate decision process by making the business case that the costs and benefits of environmental (or, more recently, sustainSavvy companies know they must able development and do more than just comply with social responsibility) applicable regulations. They issues should be decidrecognize that they will be held to ing factors when evalhigher standards of performance. uating certain business options. If the decision clearly involves compliance-related matters, the discussion can be briefand favorable to the position of the environmental professional. Companies rarely make a conscious decision to defy legal requirements. But most of the time, regulations cannot provide support for the environmental professionals position. Often, the factors under consideration involve intangibles that defy precise quantification. Yet intuitively, managers may recognize that such factors have significant potential to affect the companyby, for example, impacting the companys brand or reputation.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Savvy companies know they must do more than just comply with applicable regulations. They recognize that they will be held to higher standards of performance. When making the inevitable trade-offs involved in any major business decision, regulatory compliance can at best serve as an initial screening test. So even if a proposed action is legal or is not covered by current regulations, business managers must ask further questions before making their decision: Do the benefits of the action outweigh the costs? What is the anticipated rate of return?

Pricing the Intangible

Not surprisingly, the process of trying to put a price tag on intangibles has received considerable attention from academicians. For example,

Environmental Leadership

Environmental Quality Management / DOI 10.1002/tqem / Spring 2011 / 105

Alan Holland claims that cost-benefit analysis is based on the (perhaps faulty) assumption that all people are consistently reasonable and have preset values at which they would be willing to buy or sell things like health, safety, or water quality.5 Others claim that cost-benefit analysis turns all intangibles into commodities for salesomething most of us would not approve of in the case of disease prevention or safety.6 Finally, some argue that, by its very nature, cost-benefit analysis tragically decreases the value that society places on the intangibles in question. If an intangible good like worker safety is for sale, why should employers unconditionally strive to protect it?

choices are. It can be an effective way to prevent them from putting themselves to shame in front of their friends and family. Cost-benefit analysis forces decision makers to frankly compare the importance of all things involved. Its transparency, reliance on explicit valuation, and focus on consequences make costbenefit analysis a tool that can challenge perverse trade-offs in cases where regulation is lacking or absent.

The Real Decision-Making Process in Corporations: Confronting Culture and Governance Issues

Regulations and establishing the business case may dominate the open or transparent side of management decision making, but many other, less obvious factors are also in play. These factors are every bit as important when seeking to understand the ethical dimensions of the potential trade-offs involved with sustainable development. The real decision-making processes that go on within companies may be complexand often far from transparent. The sections that follow discuss some of the corporate cultural and governance issues that can impede sound decision making.

Forcing the Issue

Criticisms notwithstanding, cost-benefit analysis has virtues that make it highly valuable to decision makSeeing the cost of their actions in ers. It forces them to dollars and cents can bring home take a cold, hard look to decision makers how crucial at the consequences of their choices are. their potential courses of action. It also allows them to examine the priorities inherent in the decisions they make. Difficult decisions always involve placing an implicit price tag on intangibles, even if decision makers prefer not to admit it. By forcing decision makers to assign an explicit price, cost-benefit analysis requires them to come up with a number that can help guide their decision. Having an explicit number to work with (instead of just a vague intuitive sense) can encourage decision makers to act in a way that is socially or morally acceptableby, for example, valuing environmental quality more than the new corporate expansion. Seeing the cost of their actions in dollars and cents can bring home to decision makers how crucial their

Using Facts SelectivelyIf at All

Top executives sometimes opt to go with their gut instincts, disregarding inconvenient facts. Or they may simply decide to agree with people who provide recommendations that are to their liking.

Information Barriers

In many cases, the relevant facts may never get to decision makers in the first place. For example, EHS professionals may not be allowed enough face time to educate executives in ways that would allow them to make truly informed decisions.

106 / Spring 2011 / Environmental Quality Management / DOI 10.1002/tqem

Richard MacLean and Kimberly Abeel

In addition, information often gets filtered as it makes its path to top management or across organizations. Perhaps the best example of such a filter is the boss who refuses to convey bad news. But this failure to communicate actually tends to be much more pervasive in business organizations.

Fragmented Information

Sometimes the lack of open communication across functional areas can lead to bad decisions or no action at all. This is particularly true when each group within the organization has only partial information and there is no central mechanism that can pull all the pieces together into a compelling business case. When viewed separately, the individual bits of evidence might look unconvincing. As a result, no one feels compelled to do anything.

The Data Hurdle

Whole organizations, not just individuals, may collectively hold certain beliefs or insist on certain processes. For example, some organizations develop a powerful data-driven culture in which everyone has to prove beyond some threshold hurdle (usually in specific financial or statistical terms) that the threat or opportunity they are highlighting is worthy of further consideration. But, as already noted, intangible or ambiguous threats and opportunities can be phenomenally challenging to quantify. In such cases, documenting a compelling business case that passes muster can be all but impossible, especially since the resources required to research and formulate a truly sound business case can be out of reach for the typical EHS professional. When this happens, environmental managers can find themselves caught in a classic no-win, catch-22 situation.

Differing Tolerances for Risk

Individuals also have different tolerances for risk. Environmental professionals and attorneys tend to be Organizational conformity more risk-averse. By and groupthink can stifle contrast, business exunconventional ideas and prevent ecutives, and espeinformed individuals from raising cially sales and maran alarm when they identify an keting staffs, tend to important issue. be much more willing to take chances. A can-do attitude is valued highly in the business world. Confidence (even overconfidence) may be viewed as a positive attribute. It is no wonder that cautious environmental professionals can be seen as Eco Cops or Safety Nazis, and their concerns dismissed out of hand.

Groupthink

Organizational conformity and groupthink can stifle unconventional ideas and prevent informed individuals from raising an alarm when they identify an important issue. These individuals may be reluctant to force the issue forward if it might upset their colleagues or create problems with other functional areas. Going with the flow may be easier, especially if it seems necessary to preserve the individuals career aspirations. No one likes being viewed as a loose cannon.

Resistance to Change

Individuals within the organization may resist change and stubbornly hold onto their existing beliefs. Even environmental professionals can be blind to emerging issues. Most often, this happens because they are focused totally on the crisis du jour or on maintaining regulatory compliance. Unfortunately, however, a few can be so convinced of their individual prowess that they fail to see the value of an occasional independent assessment.

Environmental Leadership

Environmental Quality Management / DOI 10.1002/tqem / Spring 2011 / 107

Reluctance to Identify Issues or Admit Error

Some individuals may fear raising previously undiscovered governance issues, worrying that by doing so they may create problems for themselves. Why rock any boats? might be their motto. In addition, people often do not like to admit errors, either to themselves or to others. Even if emerging facts directly challenge their beliefs, some may persist on the same flawed path. They prefer to selectively choose information that conforms to their own beliefs, going so far as to surround themselves with submissive yes men and accommodating consultants.

Each of these has weaknesses. Brown notes, The dominant theory in business is Utilitarianism whose weakest points are the need for complete knowledge of the future and assigned dollar values to every outcome. Failure to understand those limitations forms the foundation of much of the environmental and health damage from governmental decision making.9

Placing Ethical Boundaries on Business

In a much-cited 1970 New York Times essay called The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,10 economist Milton Friedman declared that businesses do not have social responsibilities beyond earning a return for their shareholders; only individuals have such responsibilities. One of the more famous quotes from the essay states, there is one and only one social responsibility of businessto use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud. In effect, Friedman places moral and ethical boundaries on executives, arguing that they have no right to spend the monies of the corporations owners (its shareholders) in seeking to achieve social agendas other than maintaining the vitality of the companyand the inherent benefits the company provides to shareholders, employees, and the community. This argument has spawned debate between those who take a free market view (that creating wealth should be the guiding principle for corporate behavior) and those who adopt a corporate social responsibility view (that corporations should broaden their concerns beyond just making money). Which view is right? Clearly, the world has changed dramatically since Friedman wrote his essay decades ago. Most executives today advocate enlightened self-interestthe view that,

Hidden Agendas

Hidden agendas can also cause organizations to stubbornly stay the course even in the face of new or different information. This phenomSome individuals may fear raising enon can apply to any previously undiscovered governance type of organization issues, worrying that by doing corporate, governmenso they may create problems for tal, and nongovernthemselves. mental. For example, the 2010 midterm elections were generally interpreted as a repudiation of the policies pursued by the current administration in Washington, including policies directly related to environmental protection. Nonetheless, after the election, US EPA stepped up efforts to implement a range of previously announced regulations, including many that likely would not find support in the new Congress.7

Theories of Decision Making

David Brown, Sc.D., adjunct professor of applied ethics at Fairfield University, states, There are the three principle theories in decision making, Deontology (duty), Utilitarianism (outcome), and Ontology (virtue).8

108 / Spring 2011 / Environmental Quality Management / DOI 10.1002/tqem

Richard MacLean and Kimberly Abeel

although certain activities may be more costly in the short run, they can further the corporations best long-term interests. For example, corporate philanthropic activities often are justified as a means of building good, long-term community relationships that may someday pay ample dividends.

developing sustainable operations can be immediate and enduring, and sustainability need not be reduced to only a peripheral component of a successful organization.

Ethical Decision Making and Sustainable Development

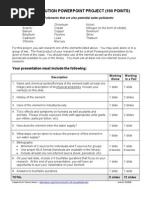

Considering the preceding points raised, what should a business executive do to ensure that he or she is making ethical trade-offs when considering issues involving sustainable development? Here is our list of the top ten key elements: 1. Determine whether your staff is competent in these areas. Since most executives do not have direct exPayoffs for developing sustainable perience with runoperations can be immediate and ning sustainable enduring, and sustainability need development and not be reduced to only a peripheral EHS groups, an excomponent of a successful ternal review may organization. be in order. We have seen far too many individuals assigned to head up these functional areas even though they lack the requisite expertise. On-the-job training is not acceptable if the stakes are potentially high. 2. Review your companys vision, mission, and policy statements relating to sustainability and EHS concerns. You may find that they sound more like value statements than any real reflection of how the company operates. If so, create a new set based on thoughtful review of what your company is really trying to accomplish. Ask yourself the question, Are these clear and actionable statements, or do they merely sound politically correct? 3. Do not interpret a record of excellence in EHS compliance as an indicator of superior performance. Sometimes, a spotless record simply reflects lax regulatory oversight. Regu-

Sustainability: Philanthropy or Strategy?

Some executives place sustainable development in the category of good deeds. But companies that see sustainability as a philanthropic activity are missing the greatest benefits it has to offer. Decisions based on this myopic viewpoint fail to see the risk-reduction possibilities and the potential brand-position and marketing opportunities afforded by sustainable development. Sustainability can be integral to the success of many companies today. Organizations that reduce environmental, health, and safety risks for their employees, consumers, and host communities can benefit by avoiding legal problems, bad press, and broken consumer relations down the road. This more strategic approach identifies the adverse effects business operations may have on people or the environment, seeks to mitigate or lessen the probability of these effects, and positions the business to act responsibly vis--vis society and the environment. In branding, using sustainability as a lens can remind businesses to be responsive to consumers, in addition to being responsible. Nowadays, more consumers (as many as nine out of ten) report that their values influence their spending.11 By integrating consumer values with core business practices, companies can capitalize on this. Businesses can also construct a strategy around sustainability trends in consumer preferences, continually enhancing brand appeal and consumers bond with the brand. The benefits to integrating sustainability with core strategy are virtually endless. Payoffs for

Environmental Leadership

Environmental Quality Management / DOI 10.1002/tqem / Spring 2011 / 109

lators may have failed to identify compliance issues because their priorities happen to lie elsewhere or they are short on staff. Moreover, lack of compliance problems in the past cannot serve as a forward-looking indicator of emerging issues. 4. If someone within the company appears to be a gadfly, listen: That person may have a valid point of view. Ensure that there are processes in place to bring in outside expertise to offer second opinions. 5. Establish processes that help guarantee internal communication and transparency on crucial issues, such as an ombudsman and a toll-free employee Establish a strong governance hotline. Establish an system and a set of sustainability executive advisory metrics that reflect where you are committee in which headed, not where you have been. several top executives meet directly with sustainable development and EHS staff on a quarterly basis. 6. Evaluate the substance behind your companys public relations statements relating to sustainability and EHS. Are you being fooled by your own PR? Are you mistaking external awards and placement on lists of best companies as markers of actual performance? 7. Create networks of opportunity for stakeholder involvement in sustainability and EHS issues at the local, regional, and corporate levels. 8. Get involved. Some CEOs just show up at the annual EHS awards banquet and deliver a speech others have written. Make your involvement in this area substantive, just as you would be directly involved in any other important business issue. 9. Establish a strong governance system and a set of sustainability metrics that reflect where you are headed, not where you have been. Im-

plement sustainability sign-off procedures for all new business ventures, raw materials, and products. Establish a sustainability assuranceletter process in which each business unit officer reviews and signs off on his or her area.12 10. Check for overall system effectiveness and internal coherence. Do the outcomes of your trade-offs (and the related documents, efforts, and governance mechanisms) genuinely promote social and/or environmental well-being?

The Ultimate Tests for Trade-off Decisions

Trade-offs that stand the test of time are those that can pass a couple of simple tests, as discussed below.

The Front Page Test

This test forces executives to ask, How would I feel if everything that goes on in my companys decision-making processes were to appear on the front page of the newspaper? Business executives and sustainable development professionals must assume that, sooner or later, everything they do will be disclosed to the public. Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis once said, Sunshine is the best disinfectant. When it comes to ethical decisions, his statement is absolutely true.

The What If It Were Me? Test

The second test directs executives to place themselves in the position of other parties who may be affected by their decisions. They should ask themselves, Would I want to live next to this factory/operation? and Would I want my family to be subjected to the consequences of this decision? Dont forget about the flora and fauna that have no voice at all. Professor Brown states, Sustainability forces extension of commonly held ethical theory beyond humans who can reason to include ecosystems that cannot. That extension

110 / Spring 2011 / Environmental Quality Management / DOI 10.1002/tqem

Richard MacLean and Kimberly Abeel

can be supported by either Anthropocentric or Biocentric principles, both of which are difficult to include in business decision making.13

2. Stauffer, N. (2007). MIT ethanol analysis clarifies benefits of biofuel. The MIT Energy Research Council. Available online at http://web.mit.edu/erc/spotlights/ethanol.html. 3. E-mail communication with David Brown, Sc.D., adjunct professor of applied ethics at Fairfield University, November 24, 2010. 4. Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance (Chapter 1). New York: The Free Press. 5. Holland, A. (2002). Are choices tradeoffs? In D. W. Bromley & J. Paavola (Eds.), Economics, ethics, and environmental policy: Contested choices. Malden, MA: Blackwell. 6. For an explanation of this view, see Kelman, S. (2005). Costbenefit analysis: An ethical critique. In R. N. Stavins (Ed.), Economics of the environment: Selected readings (5th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Co. 7. Review & Outlook. (2010, November 22). The EPA permitorium. Wall Street Journal, p. A18. 8. E-mail communication with David Brown, Sc.D., adjunct professor of applied ethics at Fairfield University, December 1, 2010. 9. Ibid. 10. Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine. 11. 2008 BBMG conscious consumer report. Cited in Bemporad, R., & Baranowski, M. (2008, September). Branding for sustainability. New York: BBMG. 12. See MacLean, R. (2003, March). The three levels of environmental governance. Environmental Protection, pp. 2023. Available online at http//www.RMacLeanLLC.com. 13. Brown, op. cit., note 8.

Concluding Thoughts

When companies have the proper decisionmaking processes in place, the span of factors they consider is broad. In the realm of sustainability and EHS, their questions go beyond regulatory compliance and impacts on shortterm profits. A sound decision-making process requires questioning and skepticism on the part of staff members. It also requires longer-term, more holistic consideration of the impacts that company decisions may have and how business operations may factor into the companys sustainability goals. Staff should be ontological reasoners who evaluate not only the business dynamics of any decision, but also the humanistic dimensions.

Notes

1. Myers, N., & Kent, J. (2001). Perverse subsidiesHow tax dollars can undercut the environment and the economy. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Richard MacLean is director of Richard MacLean & Associates, LLC, a management consulting firm located in Flagstaff, Arizona, and executive director of the Center for Environmental Innovation (CEI), a university-based nonprofit research organization. He can be reached at Richard@RMacLeanLLC.com. For more information, visit his website at http//www .RMacLeanLLC.com. Kimberly Abeel is a graduate student in ethics at Yale Divinity School in New Haven, Connecticut, and cocreator of the Real Life project, a program on personal and professional social responsibility at Saint Marys College in Notre Dame, Indiana. She can be reached at Kimberly.Abeel@yale.edu.

Environmental Leadership

Environmental Quality Management / DOI 10.1002/tqem / Spring 2011 / 111

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- IEEE Guide for Containing Oil Spills in SubstationsDocument30 pagesIEEE Guide for Containing Oil Spills in Substationsjuan contrerasNo ratings yet

- Water Pollution ProjectDocument3 pagesWater Pollution ProjectSaugata PoaliNo ratings yet

- The High Cost of Free Parking by Donald C ShoupDocument21 pagesThe High Cost of Free Parking by Donald C ShoupPaisley Rae100% (3)

- ETHIOPIA'S ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILEDocument132 pagesETHIOPIA'S ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILEYeneta Yotor Ze EthiopiaNo ratings yet

- Geostatistics For Soil SamplingDocument169 pagesGeostatistics For Soil SamplingMiguel Gonzalez100% (1)

- Tasmanian Dairy Products Milk Powder Processing Smithton Dpemp and Appendices A-F PDFDocument124 pagesTasmanian Dairy Products Milk Powder Processing Smithton Dpemp and Appendices A-F PDFDaivd BestNo ratings yet

- The Air Act: Salient FeaturesDocument30 pagesThe Air Act: Salient FeaturesSUFIYAN SIDDIQUINo ratings yet

- Vtpi Online TDM EncyclopediaDocument7 pagesVtpi Online TDM EncyclopediaEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Vtpi Online TDM EncyclopediaDocument7 pagesVtpi Online TDM EncyclopediaEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Vtpi Online TDM EncyclopediaDocument7 pagesVtpi Online TDM EncyclopediaEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- 832R12011 (Emerging Technologies For Wastewater Treatment - 2nd Ed.)Document188 pages832R12011 (Emerging Technologies For Wastewater Treatment - 2nd Ed.)Anonymous owMJ21JRzC100% (3)

- EPA HandbookDocument201 pagesEPA Handbookdecio ventura rodrigues miraNo ratings yet

- Shaw - Edward - Resume and Letter CombinedDocument4 pagesShaw - Edward - Resume and Letter CombinedManuel MasonNo ratings yet

- A New Moment for Carsharing in the NetherlandsDocument79 pagesA New Moment for Carsharing in the NetherlandsEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Rural Carshare Project A Thinking Exercise - 22mar14Document4 pagesRural Carshare Project A Thinking Exercise - 22mar14Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Carlite London Final Jan27Document22 pagesCarlite London Final Jan27Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- A New Moment For Carsharing in TheNetherlandsDocument6 pagesA New Moment For Carsharing in TheNetherlandsEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- WS-A New Moment For Carsharing in TheNetherlandsDocument4 pagesWS-A New Moment For Carsharing in TheNetherlandsEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Utrecht Workshop - Final Report of 14apr14Document32 pagesUtrecht Workshop - Final Report of 14apr14Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Disruptive Innovations in Ridesharing Webinar - ShaheenfinalDocument11 pagesDisruptive Innovations in Ridesharing Webinar - ShaheenfinalEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Martens Et Al 2012 - A Supply Side Approach To CarsharingDocument16 pagesMartens Et Al 2012 - A Supply Side Approach To CarsharingEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Carsharing Parking Policy Review - Shaheen Et AlDocument11 pagesCarsharing Parking Policy Review - Shaheen Et AlEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Chan Shaheen 2011 Ridesharing SurveyDocument21 pagesChan Shaheen 2011 Ridesharing SurveyEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Shoup On Carsharing and ParkingDocument18 pagesShoup On Carsharing and ParkingEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Shaheen 2008 City Strategies CarsharingDocument11 pagesShaheen 2008 City Strategies CarsharingEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Penang Final Report (Rev15 26nov13)Document77 pagesPenang Final Report (Rev15 26nov13)Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Shaheen 2008 City Strategies CarsharingDocument11 pagesShaheen 2008 City Strategies CarsharingEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Utrecht Workshop Report of 20 February 2014: - Amsterdam CommentaryDocument1 pageUtrecht Workshop Report of 20 February 2014: - Amsterdam CommentaryEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Martens - Justice As Framework - English Version-Eb NotationsDocument4 pagesMartens - Justice As Framework - English Version-Eb NotationsEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Running An Informal Car Club Carplus Best Practice Guidance May 2012Document11 pagesRunning An Informal Car Club Carplus Best Practice Guidance May 2012Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Penang Final Report Rev15 26nov13Document85 pagesPenang Final Report Rev15 26nov13Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Sustainable Penang: Toward A New Mobility Agenda. (Final Phase 1 Report, Rev10 23nov13)Document66 pagesSustainable Penang: Toward A New Mobility Agenda. (Final Phase 1 Report, Rev10 23nov13)Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Carsharing 2000 - A Hammer For Sustainable DevelopmentDocument300 pagesCarsharing 2000 - A Hammer For Sustainable DevelopmentEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Utrecht Workshop Report of 20 February 2014: - Commentary From Parkstad LimburgDocument1 pageUtrecht Workshop Report of 20 February 2014: - Commentary From Parkstad LimburgEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Going Dutch: Utrecht Workshop Report - v. 31mar14Document28 pagesGoing Dutch: Utrecht Workshop Report - v. 31mar14Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Utrecht Workshop Report of 20 February 2014: - Auto Delen ZwolleDocument1 pageUtrecht Workshop Report of 20 February 2014: - Auto Delen ZwolleEric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Penang Final Report v9 23nov13Document72 pagesPenang Final Report v9 23nov13Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- Penang - Final ReportDocument55 pagesPenang - Final ReportEric Britton (World Streets)100% (1)

- Sustainable Penang: Final Phase 1 Report (21 Nov 2013)Document57 pagesSustainable Penang: Final Phase 1 Report (21 Nov 2013)Eric Britton (World Streets)No ratings yet

- George Town February AgendaDocument96 pagesGeorge Town February AgendaThe ExaminerNo ratings yet

- Testimony 4 - Douglas W. DockeryDocument17 pagesTestimony 4 - Douglas W. DockerywgbhnewsNo ratings yet

- CMAQ 4.7.1 OGD 28june10Document210 pagesCMAQ 4.7.1 OGD 28june10Aitmemory TranNo ratings yet

- Drennan Charter Challenge DecisionDocument51 pagesDrennan Charter Challenge Decisionwindactiongroup7801No ratings yet

- Interna'onal Best Prac'ces For Pre - Processing and Co - Processing Municipal Solid Waste and Sewage Sludge in The Cement IndustryDocument25 pagesInterna'onal Best Prac'ces For Pre - Processing and Co - Processing Municipal Solid Waste and Sewage Sludge in The Cement IndustryRihem and Soundosse wordsNo ratings yet

- Ecological Effects Test Guidelines: OPPTS 850.3020 Honey Bee Acute Contact ToxicityDocument8 pagesEcological Effects Test Guidelines: OPPTS 850.3020 Honey Bee Acute Contact ToxicityNatalie Torres AnguloNo ratings yet

- Rule: Air Quality Implementation Plans Approval and Promulgation Various States: ExclusionsDocument6 pagesRule: Air Quality Implementation Plans Approval and Promulgation Various States: ExclusionsJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Letter From EPA Region 7 Administrator Karl Brooks To Missouri Coalition For The Environment, May 23, 2014Document2 pagesLetter From EPA Region 7 Administrator Karl Brooks To Missouri Coalition For The Environment, May 23, 2014EPA Region 7 (Midwest)No ratings yet

- American Water WorksDocument7 pagesAmerican Water WorksLisa SorgNo ratings yet

- Circular PSSP1-10 - Implementation of New EPA Code of Practice On WasteWater Treatment and Disposal Systems Serving Single HousesDocument5 pagesCircular PSSP1-10 - Implementation of New EPA Code of Practice On WasteWater Treatment and Disposal Systems Serving Single HousesJNo ratings yet

- Fall 2008 Waterkeeper MagazineDocument68 pagesFall 2008 Waterkeeper MagazineWaterKeeper AllianceNo ratings yet

- Thiabendazole RedDocument103 pagesThiabendazole RedFandhi Adi100% (1)

- Chemicals Evaluated For Carcinogenic Potencial Office of Pesticides Progras US-EPADocument38 pagesChemicals Evaluated For Carcinogenic Potencial Office of Pesticides Progras US-EPAniloveal2489No ratings yet

- Actuator PDFDocument34 pagesActuator PDFEnar PauNo ratings yet

- Manual LabcertificationDocument209 pagesManual LabcertificationDiahNo ratings yet

- Read Case Study: Project Overrun PMCS, Pg. 249Document7 pagesRead Case Study: Project Overrun PMCS, Pg. 249Bharat DarsiNo ratings yet

- English 202C Rhetorical AnalysisDocument2 pagesEnglish 202C Rhetorical AnalysismonaksamitNo ratings yet

- Bulk Sampling For AsbestosDocument9 pagesBulk Sampling For AsbestosHafizie ZainiNo ratings yet

- Federal Register-02-28442Document2 pagesFederal Register-02-28442POTUSNo ratings yet

- Jackson Et Al Whitepaper 2011Document12 pagesJackson Et Al Whitepaper 2011Radio-CanadaNo ratings yet

- Works Cited - Bpa Wesbite Design 2020 1Document6 pagesWorks Cited - Bpa Wesbite Design 2020 1api-491920561No ratings yet