Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Lead-Tank Fragment From Brough WATTS

Uploaded by

fionagusOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Lead-Tank Fragment From Brough WATTS

Uploaded by

fionagusCopyright:

Available Formats

A Lead Tank Fragment from Brough, Notts. (Roman 'Crococalana') Author(s): Dorothy J. Watts Source: Britannia, Vol.

26 (1995), pp. 318-322 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/526887 Accessed: 02/09/2009 16:33

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sprs. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Britannia.

http://www.jstor.org

3I8

NOTES

archaeological material held in museums and elsewhere, something which both museum professionals and researchershave been seeking for some time.

Using the Excavationlndex

The national database created and maintainedby the Index is available in a standardformat for the whole of England. It is computerised as part of the NMR's MONARCH system, allowing information retrieval to be tailored to the user's requirements. Queries may use many combinations of criteria to select information from the Index, which may be combined with monument information from the NMR's National Archaeological Record. Enquiries may be made by personal visit, letter, telephone or fax, as detailed below. On-line searching of the Index is possible in the Public Search Room in the National Monuments Record Centre. Alternatively, catalogues can be generated in answer to specific enqv}iries: charge is made to cover the a cost of printing and postage. Furtherdetails of any of these databases or collections are available from: NMR Customer Services, National Monuments Record Centre, Kemble Drive, Swindon, SN2 2GZ Telephone: oI793 4I4600 Fax: o I 793 4 I 4606

A Lead Tank Fragment from Brough, Notts. (Roman Crococalana). Dorothy J. Watts writes: Some time in the late I970S, a metal-detectoruser discovered a large object in a field east of the A46, opposite the scheduled site of Roman Crococalana (SK 837 584). The object, a sheet of decorated lead (FIG.6; PL. VI), was subsequently acquired by the Newark Museum, and remains on display there. It was assumed that the find was part of a lead coffin, since there are other coffins from the district in the museum.68 Until now no study of the piece has been undertaken. On examination, it appears that the sheet of lead was part of a container usually categorised as a circv}lar tank.69While the actual find spot is not recordedtit is likely to have been located within or near the eastern sector of the small fortified town. The close proximity of the field to a known Roman site and the similarity of the object to a number of lead tanks found in Britain make it fairly certain that it too was of Roman date, and probably of the fourth century The decoration on the fragment can readily be interpretedas Christian. If this is accepted, then the piece is importantnot only in expanding knowledge of the extent of Christianity in the fourth century, but also as the first known Christian object from this part of Roman Britain. The height of the fragment varies from 370 to 390 mm, with a slight tapering from right to left. The width ranges from 730 to 820 mm, and the thickness of the lead is 3-4 mm. A portion of the sheet which formed the base of the tank remains, and this is attached to the sides sealed between two strips of lead. The construction seems similar to, but not exactly like, that of the tanks from Burwell70 and

Kenilworth.71

Around the top of the fragment is a moulded band of lead I5-I7 mm wide, finished with an indented lower edge. The main decoration comprises two registers. The upper is a continuous frieze of Xs in applied straps or bands, I6 mm wide, separatedby pairs of narrowerverticals which appearto have been

68 69 70 71

A. Smith,Trans ThorotonSoc. xlv ( I 94I ), I o6-g; C.M.Wilson,Lincs. Hist. & Arch. vii See C.J.Guy,Britannia Xii ( I 98 I ), 27 I -6. C.J.Guy Proc. Camb.Antiq. Soc. Ixviii (I978), 2-4. C.J.Guy Trans.BirminghamWarwicks Arch. Soc. xcv (I987-8), I07-9.

( I 972),

I 0.

WaGp

X:te

j

t?_

/ -,s

s

f.X,

ze=b *

w*

'

;

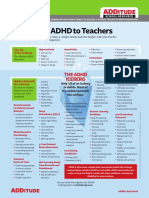

FIG. 6.

A lead tank fragmentfrom Brough, Notts. (Drawing: City of Lincoln Archaeology Unit).

W__

3 2o

NOTES

part of the original moulding. The main feature of the lower register is a device consisting of a circle overlaid by an intersecting X-and-vertical; this is flanked by a pair of Y-shaped motifs with arms at an angle of about 45 degrees and the vertical extending to the same height as the arms. The intersecting Xand-verticaland the arms of the Ys are applied bands; the circle and uprightsare moulded. The decoration appears to have been carried out with care. All applied bands are themselves decorated with a scored X-and-vertical design and the narrow verticals with a rope-like pattern. Some of this decoration, particularly on the uprights of the Ys, may have been part of the original moulding, but definition of the motifs on the other verticals is sharp, suggesting that much of the decoration was done after casting. The lower edges of all the applied strapsare finished with a V-shaped indentation. There is no evidence that any violence had been used in breaking up the original vessel. The edges appear to have been cut with a sharp object, although there is some tearing and bending at the top right corner,where the reinforced edge may have made it more difficult to cut. The height of the Eighteen or so whole or partial circular lead tanks are known from Roman Britain.72 (405 and 355 mm), Icklingham piece (370-390 mm) compares with the tanks from Bourton-on-the-Water (370 and 330 mm), Ashton (380 mm), and Huntingdon (400 mm).73If these are any guide, the diameter of the Brough tank was probably in the range of 8Io-g6s mm. The decoration is also comparablewith that found on other tanks. It does, however, have some features which are unique on such vessels, though found elsewhere in Roman Britain and in a Christian context. The X motif with separate verticals is found on seven tanks or fragments: Pulborough, Willingham, (two), Huntingdon,and Ashton.74The last two of these have circles in Caversham,Bourton-on-the-Water the four triangles formed by the X. The Pulborough and Caversham tanks also have a Chi-rho as decoration. In an earlier study,75it was shown that the X was a form of the Christian cross, the crux decussataor St Andrew's cross, and that its presence on these tanks, with or without an accompanying Chi-rho, was an indication that the symbol had an association with Christianity.76 The Y-type devices reinforce this interpretation.To date, no similar symbol has been found on a lead tank in Roman Britain, but there has been a non-functional metal object in the shape of a Y found in a This object was noted by Sparey Green in Ig82.78 In a more grave in the cemetery at Poundbury.77 detailed study by the present author, it was concluded that the object gave further weight to a Christian The symbol, as it appears on the Brough tank, resembles that still identity for the Poundburycemetery.79 found today on chasubles, with the vertical of the Y extended upwards about the same height as the diagonals. This then resembles the oransattitude, found in early Christianart and - most significantly for The our purpose here - on the walls of the house church at Lullingstone. It was equated with the cross.8() Y symbol was also seen as representing moral choice, an idea borrowed from the Greeks.81 Such a symbol, with the implication of making a choice for good or evil, would be a singularly appropriate decoration on a vessel used in Christian baptism, a religious ritual in which the candidate was asked to renounce the devil and all his works. Although the X and Y symbols point to Christianity and may both be seen, among other interpretations,as representing the cross, it is the intersecting X-and-vertical superimposed on a circle

tank (undecorated) hassince (I99I), t58-75. A further Britai71 Christians and Pagans in Ronla71 72 See D.J.Watts, Archaeology by kindlysupplied Dr Ben Whitwell, (Information beenfoundat Riby,Lincs.,but its dateis uncertain. Council.) County Unit,Humberside up of cit. (note7X),tableI fora summary sizes of tanksdiscovered to t989. 73 See Guy,o,p. op. cit. (note72), figs 23 (d), (f), 24 (a-e). 74 See Watts, in updated the t99t publication A7ltiq.Jour7l. lxviii (t988), 2Io-22. This paperwas subsequently 75 D.J. Watts, op. (Watts, cit. (note72)). Misopogo 60 I 1.3 includeIsidore,Orige71 andpossiblyJustinMartyr, Apologwn andJulian, references 76 Ancient 357A Poundbltr. 2. The Cemeteries (I993), fig. 83.40 in Gravet339. andT.I.Molleson, 77 D.E.Farwell 78 L. Keen(ed.),Proc. Dorset Nat. Hist. Arch. Soc. Ci ( I 98 I ), I 33. in to op. cit. (note72), I73-8. Thegravebelonged a male,nota female,as reported thatpublication. 79 See Watts, Epistle I2.2. Felix,Octavius 29.6; andpossiblyBarnabas, 80 e.g. Municius op. Et>mologiae 1.3.7. See Watts, cit. (note72), I77 andnotes. 81 e.g. Isidore,

NOTES

32 I

which is clearly the central motif on the fragment. It was presumably also the focal point of the complete veLssel.In Christian symbolism the device represents the initial letters of IHEOYS XPISTOS (Jesus Christ). This Iota-chi X combination was probably the earliest Christian monogram, preceding the Chirho i ,89 which became widely used after the conversion of Constantine in 3 I2. At least two inscriptions using the Iota-chi monogram in place of the words 'Jesus Christ' are known from as early as the third century. The first, of about A.D. 270, is from Phrygia, and concludes with the words ESTAI AYTQ IIPOS TON X ('he will have to account to Jesus Christ').83The second, from Rome, can be positively dated to 269, and includes the phrase [IN] X DN = (IN) IESU CHRISTO DOMINO NOSTRO ('in Jesus Christ our Lord').84 A third example, also from Rome,85 evidently predates the Council of Nicaea of 325 (and affirmation of the nature of the Trinity), since it reads AVGVRINEIN DOM ET X ('Augurinus, (may you rest) in (our) Lord and Jesus Christ'). By the early part of the fourth century, the monogram had come to be used as a symbol, ratherthan as an abbreviation.86 Nevertheless, it continued to be found in various parts of the Empire. Later examples from Egypt87and Rome88date from the sixth and seventh century.89 The Iota-chi may, therefore, be set securely within the context of Christianmonograms and symbols of the third to seventh centuries. Its presence in Roman Britain on various artefacts cannot be seen as unusual. While the Brough fragment is the only known example of the use of the device as decoration on a lead tank, there are other artefacts from Britain which bear the monogram.90 Two of these have known Christian symbols besides the Iota-chi. One is an importantpiece in the British Museum, a pewter plate from Stamford;it has a central motif of Iota-chi, encircled by crosses of the decussata type, palm leaves, and two simplified Chi-rho symbols.9' The other is a pottery platter from Lankhills cemetery, with an Iota-chi on one side and what may be a stylised fish on the reverse.92The platter was found with burials in Feature6, an enclosure which is believed to have contained the graves of Christians.93 On the Broughfragment,the prominenceof the Iota-chi is enhancedby the circle, over which the strapsof lead forming the monogramwere laid. Circles are found on a numberof lead tanks from Britain,including those from Huntingdon,Oxborough, Burwell, Ireby, Wilbraham,and perhaps Cambridge.The device has been variously interpreted representing as eternity,the world, the cosmos, and an everlastingGod, as well as a wreath of triumph.94 is found in Christian contexts, standing alone and in conjunction with another It symbol. In the lattercase, this may be seen as intensifyingthe religious significanceof both symbols.95 It will thus be seen that we have considerable evidence for a Christian identity for the lead fragment, and parallels from Roman Britain for the complete vessel. The purpose of these tanks has been frequently discussed,96and the writer has proposed that they were used at Christian baptism for performing a footwashing ritual. For this paper, however, the importance of the object lies not in its purpose but in its

xn e.g. W.M. Ramsay, Cities azldBishopricslJfPhrygial.I (I897), 526-7; O. Marucchi, Christia7l Epigraphy reprint I974), 59; M. Sulzberger,Byza71tios1 ii (I925), 393-7. xX CIG 39020. This seems to be a variant on the formula estott oevtci) zpo5 tov 0gov ('he will have to account to God'), which was common in Christianinscriptions in Asia Minor (Ramsay, op. cit. (note 82), SI4-I6). XAG.B. DeRossi, Is1scriptio7les Christias1cle UrbisRost1ae I (I86I), I6, no. IO. XS G.B. DeRossi, La Roselbl Sl)tterras1ea Cristias1a (I867), pl. xxxix, no. 30. 11 86 Sulzberger,op. cit. (note 82), 397. X7 e.g. P.Oxy. I.I26 (A.D. 572), I36 (A.D. 583), I37 (A.D. 584), I38 (A.D. 6IO-II). This last document, although secular in nature,begins with a Christian invocation. xx e.g. E. Diehl, Is:1scriptios1es Latis1ae Christias1ae Veteres (I925), no. 84I (A.D. 584). I 89 The monogram is used only as a symbol in these examples. 9() See Watts, op. cit. (note 72), ISI; 245, n. 9. 91 Now RIB(Vol. 11)24I7.4I. 9' G. Clarke,Pre-RSoznas1Roznas1 clzld Wis:1chester II: TheRSoena7l Part Cemetenx La7lkhills at (I979), 430; fig. 82.256. 93 Watts, op. cit. (note 72), passisel. 94 ibid., I63-6. 95 H. Child and D. Colles, Christias1 Symbols (I97I), 27. 96 See Watts, op. cit. (note 72), I69, for the main theories, and for furtherdetails of the argumentpresented in this present paper.

(I9IO,

3 22

NOTES

identification as part of a vessel decorated with Christian symbols. It adds to our corpus of similar objects in Roman Britain, and to finds with a Christian identity. It also extends knowledge of the distributionof Romano-BritishChristianity. Little is known about Roman Crococalana. It was established towards the end of the first century. The Coins and pottery to the end of the fourth century have been found on both sides of the Fosse Way.97 town appearsto have been fortified in the third century,perhapsbecause of its position between Leicester The and Lincoln, and is one of only five such fortified small towns on this section of the Roman road.98 earliest known excavations were those by Woolley in Ig06,99 in the north-east sector of the enclosure. It is the area east of the A46 which also yielded the lead fragment.'However, in view of the threat to the scheduled site by proposed road widening, the watching brief in I980 and subsequent geophysical surveys in I990 and I99I were concentratedon the area west of the Fosse Way. Archaeological evidence, such as painted wall-plaster, imported pottery, glass, and bronzework, suggests some wealth in the town; but, in the absence of large-scale excavation at the site, little of the activities of Roman Brough can be deduced, and even less the religious beliefs of the inhabitants. Evidence for Christianity in the area generally is sparse. The nearest large centre, and one with a Christian presence, was Lincoln, about I6 km north of Brough. Ancaster, some 20 km to the south east, had a cemetery which appears to have been Christian;'' and recently a fragment of a comma-terminal implement decorated with a Chi-rho was found there.'02The lead piece is thus of great importance in establishing a Christian presence in the Brough area during the Roman period. It is the first such evidence from Nottinghamshire. It raises considerable interest in the scheduled site just across the A46 from the field where the object was found and even greater interest in the field itself. It is known that the lead coffin discovered during World WarII was found east of the area explored by Woolley early this century. A geophysical survey of the field might, therefore, be profitably undertaken. The state of the lead fragment is also of great interest. A number of tanks have been found in a fragmentarystate only; some appear to have been deliberately damaged, or to have been abandoned in unusualplaces such as wells or streams.Guy has suggested that such treatmentis evidence of the revival of While the actual provenance of the Brough find is not known, the paganism in the late fourth century.'03 sheet of lead appears to have been carefully cut. It does not seem to have been subjected to violent treatment,or to the kind of damage that would be caused if the whole vessel had been broken up for reuse of the lead. Nevertheless, its condition could also fit the theory of pagan revival. If, as has been proposed,'04 Christianityin certainareas was underpressureas a result of the efforts of the pagan emperor,Julian,and of the policy of religious tolerationof his (Christian)successors, the Brough lead fragmentmight be evidence of such pressure.Christians,anxious to preserve the sacred monogramon a lead tank which was no longer in use for baptisms,may themselves have cut the piece out and hidden it away from pagan zealots. Such opinion is, at this stage, only speculative. Further research and excavation may help to solve some of the problems. In the meantime, we may be fairly confident in adding the lead fragment from Brough to the list of artefacts with Christian symbols, and thus to our knowledge of Christianity in Roman Britain.'05 Departmentof Classics and Ancient History, The Universityof Queensland

Notts.II (I970), II-I5. V.C.H. Britain(I990), 35, 3I5. of The Towns' Roman and B. Burnham J. Wacher, 'Small Soc. Tra7ls. Thoroto7l x (I9IO), 63-72. T.C.S.Woolley, by kindlysupplied MrV.Radcliffe. 00 Information op. 01 Watts, cit. (note72), ch. III etpassim. Museum. 102 Thisitemis nowin theBritish op. cit. (note69), 275. 03 Guy, op. cit. (note72), 22I-7. 04 Watts, this Councilfor funding Research and of to are 105My thanks extended The University Queensland the Australian the and Unit for organising supplying drawing to research, Mr MichaelJonesandthe City of LincolnArchaeology the to for Museum permission publish object. and andphotograph, to Newark

97 98 99

PLATEVI

oo

sov

CX

Ct

You might also like

- Ancient Iron Spear and Javelin Unearthed in WalesDocument4 pagesAncient Iron Spear and Javelin Unearthed in WalesStanisław DisęNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Institute of America American Journal of ArchaeologyDocument17 pagesArchaeological Institute of America American Journal of Archaeologygkavvadias2010No ratings yet

- Britannia Volume 9 Issue 1978 R. P. Wright - Tile-Stamps of The Ninth Legion Found in BritainDocument5 pagesBritannia Volume 9 Issue 1978 R. P. Wright - Tile-Stamps of The Ninth Legion Found in BritainPortoInfernoNo ratings yet

- Anglo Saxon GravesDocument70 pagesAnglo Saxon GravesSjoerd Aarts100% (1)

- The Roman Lead Tank From Perry OaksDocument3 pagesThe Roman Lead Tank From Perry OaksFramework Archaeology100% (1)

- Beaker Age Bracers in England: Sources, Function and UseDocument14 pagesBeaker Age Bracers in England: Sources, Function and UseBogyeszArchNo ratings yet

- Splitting the Difference or Taking a New Approach to Roman Britain's DeclineDocument4 pagesSplitting the Difference or Taking a New Approach to Roman Britain's DeclineIonutz IonutzNo ratings yet

- Journal of Roman Pottery Studies: Volume 9 - The Roman Pottery Kilns at Rossington Bridge Excavations 1956-1961From EverandJournal of Roman Pottery Studies: Volume 9 - The Roman Pottery Kilns at Rossington Bridge Excavations 1956-1961No ratings yet

- 310343Document68 pages310343plotini7No ratings yet

- Dress and Society: Contributions from ArchaeologyFrom EverandDress and Society: Contributions from ArchaeologyT. F. MartinNo ratings yet

- Hadrian's Wall (Osprey, Fortress #2)Document65 pagesHadrian's Wall (Osprey, Fortress #2)elorran100% (16)

- Roman Military Knives of the 4th CenturyDocument6 pagesRoman Military Knives of the 4th CenturyMárk György Kis100% (1)

- 1993 110 Researches and Discoveries Archaeological Notes from Maidstone MuseumDocument15 pages1993 110 Researches and Discoveries Archaeological Notes from Maidstone MuseumleongorissenNo ratings yet

- The 4 Coronati Lodge (BAXTER, Roderick)Document86 pagesThe 4 Coronati Lodge (BAXTER, Roderick)Claudio FerrazNo ratings yet

- Bath-House at Antonin WallDocument47 pagesBath-House at Antonin WallBritta BurkhardtNo ratings yet

- Vizier Paser JEA74Document24 pagesVizier Paser JEA74Alexandre Herrero Pardo100% (1)

- British Smooth-Bore ArtilleryDocument596 pagesBritish Smooth-Bore ArtilleryThomas Wiesner100% (3)

- Encyclopedia of AntiquitiesDocument512 pagesEncyclopedia of AntiquitiesSolo Doe100% (2)

- The Pocket Guide to Outdoor Knots: A Step-By-Step Guide to the Most Important Knots for Fishermen, Boaters, Campers, and ClimbersFrom EverandThe Pocket Guide to Outdoor Knots: A Step-By-Step Guide to the Most Important Knots for Fishermen, Boaters, Campers, and ClimbersNo ratings yet

- Evidence From Dura Europos For The Origins of Late Roman HelmetsDocument29 pagesEvidence From Dura Europos For The Origins of Late Roman Helmetssupiuliluma100% (1)

- 1989 Lang BM X-RayDocument42 pages1989 Lang BM X-RaySiscu Livesin DetroitNo ratings yet

- Quator Coronati Lodge PDFDocument86 pagesQuator Coronati Lodge PDFjuncatv2250% (2)

- Society For The Promotion of Roman Studies and Cambridge University Press Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, BritanniaDocument3 pagesSociety For The Promotion of Roman Studies and Cambridge University Press Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Britannialouromartins928No ratings yet

- 5 001 070 PDFDocument70 pages5 001 070 PDFFrancis HaganNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument216 pagesUntitledRichard PatriousNo ratings yet

- Tools and ImplementsDocument38 pagesTools and ImplementsCindrella ElbadryNo ratings yet

- Auxiliary Barracks in Anew Light, N.hodgson, P.T, BidwellDocument38 pagesAuxiliary Barracks in Anew Light, N.hodgson, P.T, BidwellSasa ZivanovicNo ratings yet

- Merovinian Gold BraidsDocument45 pagesMerovinian Gold BraidsLibby Brooks100% (2)

- Round Mounds and Monumentality in the British Neolithic and BeyondFrom EverandRound Mounds and Monumentality in the British Neolithic and BeyondNo ratings yet

- The Origin and Date of The Bayeux EmbroideryDocument8 pagesThe Origin and Date of The Bayeux EmbroiderydanaethomNo ratings yet

- Nuts and BoltsDocument7 pagesNuts and BoltsMuDasirNo ratings yet

- Cambourne - MetalworkDocument21 pagesCambourne - MetalworkWessex ArchaeologyNo ratings yet

- Fragments of the Bronze Age: The Destruction and Deposition of Metalwork in South-West Britain and its Wider ContextFrom EverandFragments of the Bronze Age: The Destruction and Deposition of Metalwork in South-West Britain and its Wider ContextNo ratings yet

- Evidence for Early Medieval lucets and braiding in Britain and ScandinaviaDocument7 pagesEvidence for Early Medieval lucets and braiding in Britain and Scandinaviasonnyoneand20% (1)

- CBA-SW Newsletter #8Document16 pagesCBA-SW Newsletter #8Digital DiggingNo ratings yet

- ROGER LING-Inscriptions On Romano-British Mosaics and Wail PaintingsDocument30 pagesROGER LING-Inscriptions On Romano-British Mosaics and Wail PaintingsChristopher CarrNo ratings yet

- Journal of Roman Pottery Studies: Volume 19From EverandJournal of Roman Pottery Studies: Volume 19Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Materialising the Roman EmpireFrom EverandMaterialising the Roman EmpireJeremy TannerNo ratings yet

- Celtic Metalwork of The Fifth and Sixth Centuries A. D. A Re-AppraisalDocument63 pagesCeltic Metalwork of The Fifth and Sixth Centuries A. D. A Re-AppraisalLycanthropeL100% (1)

- Society For The Promotion of Roman Studies Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and ExtendDocument3 pagesSociety For The Promotion of Roman Studies Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and ExtendSasa ZivanovicNo ratings yet

- C. J. Arnold - An Archaeology of The Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms (1997, Routledge) PDFDocument278 pagesC. J. Arnold - An Archaeology of The Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms (1997, Routledge) PDFBaud Wolf100% (3)

- CAR-report-0001Document99 pagesCAR-report-0001leongorissenNo ratings yet

- Later Aegean Bronze Swords: Types C and DDocument46 pagesLater Aegean Bronze Swords: Types C and DMaria-Magdalena Stefan100% (1)

- Ancient Armour and Weapons in Europe 1855Document424 pagesAncient Armour and Weapons in Europe 1855Mr Thane100% (1)

- Early Christian and Byzantine Rings in The Zucker Family CollectionDocument13 pagesEarly Christian and Byzantine Rings in The Zucker Family CollectionMrTwo BeersNo ratings yet

- Mesolithic Sites in England and WalesDocument537 pagesMesolithic Sites in England and WalesLorac ArievlisNo ratings yet

- Bell's Cathedrals: The Cathedral Church of York: A Description of Its Fabric and A Brief History of the Archi-Episcopal SeeFrom EverandBell's Cathedrals: The Cathedral Church of York: A Description of Its Fabric and A Brief History of the Archi-Episcopal SeeNo ratings yet

- Jean Carmignac enDocument7 pagesJean Carmignac enleipsanothikiNo ratings yet

- Lamb Ay MacalisterDocument13 pagesLamb Ay MacalisterCiara HoweNo ratings yet

- Allied Coastal Forces of World War II: Volume I: Fairmile Designs & US Submarine ChasersFrom EverandAllied Coastal Forces of World War II: Volume I: Fairmile Designs & US Submarine ChasersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- ClimateDocument15 pagesClimatefionagusNo ratings yet

- 14.8 Telltown Impact Assessment ReportDocument102 pages14.8 Telltown Impact Assessment ReportfionagusNo ratings yet

- Report Tate TroalenDocument5 pagesReport Tate TroalenfionagusNo ratings yet

- Woad, Tatooing and IdentityDocument20 pagesWoad, Tatooing and IdentityfionagusNo ratings yet

- Catalog Morgan MerovingianDocument144 pagesCatalog Morgan Merovingiansonnyoneand2No ratings yet

- Romano British TablesDocument12 pagesRomano British TablesfionagusNo ratings yet

- Book-Making in Early IrelandDocument6 pagesBook-Making in Early IrelandfionagusNo ratings yet

- 11 - 04 - BarlArchaeology and Belief in The Roman World: An Iconoclast's ApproachowDocument4 pages11 - 04 - BarlArchaeology and Belief in The Roman World: An Iconoclast's ApproachowfionagusNo ratings yet

- 14.8 Telltown Impact Assessment ReportDocument102 pages14.8 Telltown Impact Assessment ReportfionagusNo ratings yet

- LucernaDocument19 pagesLucernafionagusNo ratings yet

- Lucerna 19Document15 pagesLucerna 19fionagusNo ratings yet

- Woad, Tatooing and IdentityDocument20 pagesWoad, Tatooing and IdentityfionagusNo ratings yet

- A Little-Known Celtic Stone HeadDocument23 pagesA Little-Known Celtic Stone HeadfionagusNo ratings yet

- Guide To Provincial Roman and Barbarian Metalwork and Jewelry in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtDocument31 pagesGuide To Provincial Roman and Barbarian Metalwork and Jewelry in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtfionagusNo ratings yet

- Jacobsthall Early Celtic ArtDocument11 pagesJacobsthall Early Celtic ArtfionagusNo ratings yet

- UG022510 International GCSE in Business Studies 4BS0 For WebDocument57 pagesUG022510 International GCSE in Business Studies 4BS0 For WebAnonymous 8aj9gk7GCLNo ratings yet

- Chronic Pancreatitis - Management - UpToDateDocument22 pagesChronic Pancreatitis - Management - UpToDateJose Miranda ChavezNo ratings yet

- Trang Bidv TDocument9 pagesTrang Bidv Tgam nguyenNo ratings yet

- 12.1 MagazineDocument44 pages12.1 Magazineabdelhamed aliNo ratings yet

- 2 - How To Create Business ValueDocument16 pages2 - How To Create Business ValueSorin GabrielNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 DIASSDocument3 pagesActivity 1 DIASSLJ FamatiganNo ratings yet

- Pale Case Digest Batch 2 2019 2020Document26 pagesPale Case Digest Batch 2 2019 2020Carmii HoNo ratings yet

- Technical Contract for 0.5-4X1300 Slitting LineDocument12 pagesTechnical Contract for 0.5-4X1300 Slitting LineTjNo ratings yet

- Explaining ADHD To TeachersDocument1 pageExplaining ADHD To TeachersChris100% (2)

- Arx Occasional Papers - Hospitaller Gunpowder MagazinesDocument76 pagesArx Occasional Papers - Hospitaller Gunpowder MagazinesJohn Spiteri GingellNo ratings yet

- FOCGB4 Utest VG 5ADocument1 pageFOCGB4 Utest VG 5Asimple footballNo ratings yet

- PHEI Yield Curve: Daily Fair Price & Yield Indonesia Government Securities November 2, 2020Document3 pagesPHEI Yield Curve: Daily Fair Price & Yield Indonesia Government Securities November 2, 2020Nope Nope NopeNo ratings yet

- Tax Q and A 1Document2 pagesTax Q and A 1Marivie UyNo ratings yet

- Autos MalaysiaDocument45 pagesAutos MalaysiaNicholas AngNo ratings yet

- Markle 1999 Shield VeriaDocument37 pagesMarkle 1999 Shield VeriaMads Sondre PrøitzNo ratings yet

- HERBAL SHAMPOO PPT by SAILI RAJPUTDocument24 pagesHERBAL SHAMPOO PPT by SAILI RAJPUTSaili Rajput100% (1)

- Kids' Web 1 S&s PDFDocument1 pageKids' Web 1 S&s PDFkkpereiraNo ratings yet

- National Family Welfare ProgramDocument24 pagesNational Family Welfare Programminnu100% (1)

- Group 9 - LLIR ProjectDocument8 pagesGroup 9 - LLIR ProjectRahul RaoNo ratings yet

- Wonder at The Edge of The WorldDocument3 pagesWonder at The Edge of The WorldLittle, Brown Books for Young Readers0% (1)

- Complicated Grief Treatment Instruction ManualDocument276 pagesComplicated Grief Treatment Instruction ManualFrancisco Matías Ponce Miranda100% (3)

- The Wild PartyDocument3 pagesThe Wild PartyMeganMcArthurNo ratings yet

- Hadden Public Financial Management in Government of KosovoDocument11 pagesHadden Public Financial Management in Government of KosovoInternational Consortium on Governmental Financial ManagementNo ratings yet

- Setting MemcacheDocument2 pagesSetting MemcacheHendra CahyanaNo ratings yet

- Consent 1095 1107Document3 pagesConsent 1095 1107Pervil BolanteNo ratings yet

- Transformation of Chinese ArchaeologyDocument36 pagesTransformation of Chinese ArchaeologyGilbert QuNo ratings yet

- 14 Jet Mykles - Heaven Sent 5 - GenesisDocument124 pages14 Jet Mykles - Heaven Sent 5 - Genesiskeikey2050% (2)

- Detailed Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesDetailed Lesson PlanHazel Mae HerreraNo ratings yet

- AFRICAN SYSTEMS OF KINSHIP AND MARRIAGEDocument34 pagesAFRICAN SYSTEMS OF KINSHIP AND MARRIAGEjudassantos100% (2)

- 110 TOP Survey Interview QuestionsDocument18 pages110 TOP Survey Interview QuestionsImmu100% (1)