Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Best Mistakes

Uploaded by

Bilal BhatyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Best Mistakes

Uploaded by

Bilal BhatyCopyright:

Available Formats

My best mistake

The wrong turns that put executives on the right track

BY PATRICIA COBE, KATHRYN HAWKINS AND PETER ROMEO

I lost my cool-at the wrong person

President, Cinnabon

ot long after rising into herfirstexecutive post at a casual chain, ICat Cole learned that higher-ups don't always make the soundest decisions. But what haunted her after a particularly rash directive from above was how she reacted. "We were launching a massive menu initiative. I was in charge of the research and training," she recounts. Big support was ready to be rolled into the field. "Then I got a call from one of our operators in thefield,"she continues. "One of the higher-ups just wanted to throw the initiative out there and see if it sticks." No advance training, no ramp-up, just run and gun. Cole, now president of the Cinnabon bakery chain, admits she was rash in her response. "I was so young," she says. "I picked up the phone and called this executive, 'Why are you doing this? Don't you realize how important training is?"' The rollout proceeded despite her protests. She realized the superiors were going to prevail, and all she did was "make matters worse." "Reacting that way," she says, "you're going to have a short career. The lesson for me was learning the power of diplomacy. It's always best to take a breath and to ask some questions instead of freaking out." Embarrassed and convinced "I had just screwed my career," she conditioned herself for the better part of a year to react "more strategically." "It was a very humbling experience and a critical point of education," she recalls. Mistake Pain Index: (G)

Q :

<

P

u

I

CL <

< a.

(3

Restaurant Business

August 2011 www.monkeydish.com

Mistake Pain Index

MINOR SOUL CRUSHING

10

I waited too long to get rid of dead weight Bob Bai'ry

COO, Green Turtle Franchising

arly in his career. Bob Barry, currently COO ofthe Creen Turtle Franchising Group, made the same mistake over and over again. "I didn't act quickly enough to make managerial changes when things weren't going in the right direction. Instead, I tried to work with managers' weaknesses." Eventually, Barry realized that he needed to separate his caring personality from his business persona. "If you give people the proper tools and the right direction, but they still don't get it, they are moving themselves out," he says. These days, Barry is passionate about hiring the best people and investing in their training. He also advocates hiring managers who are smarter than he is.

tion is extremely important, we took that decision-making back to four key people, myself included," he notes. Although the team cannot physically visit every potential site, they use Google Maps to simulate the experience. This personalized approach has directed Smashburger on a smart, controlled path toward growth. It now counts 103 restaurants in operation45 corporate locations and 58 franchised with plans to open another 85 this year. And Prokupek remains in favor of making mistakes. "The Smashburger culture is high-risk and we 'budget' for lots of little mistakes. That's what seeds ideas and that's what led us to where we are today."

Mistake Pain Index: (5)

Too much of my menu was outsourced Kerry Kramp

CEO and President, Sizzler

Mistake Pain Index: ()

We grew too fast David Prokupek

CEO and Chairman, Smashburger

mashburger was founded in 2007 in Denver, Colorado, and in its second year, went from four locations to 20. "It was like we grew overnight," says CEO and Chairman David Prokupek From the beginning, Smashburger's intention was to measure success in the quality ofthe units they openednot the quantityand Prokupek felt it was time to return to that goal. So he slowed corporate store growth for 18 months and instituted a dramatic change approving sites. "Since real estate selec-

hen Kerry Kramp returned to Sizzler USA in 2008 to spearhead a turnaround, his first priority was the food. "We worked with an outside supplier to re-create products that our culinary team had developed. When we conducted product cuttings, we said, 'It's almost exactly the same,' but something was lacking. Guests didn't think it tasted exactly the same. Plus, it hurt me as a food personI didn't feel a connection to the product. Our kitchen staff felt they had little control over the outcome and little emotional connection to the food," says Kramp. Kramp realized how important it is for hourly employees to feel that connection to the menu by making items from scratch. It also empowers them, and that helps them connect better to the guests.

Mistake Pain Index: @

Restaurant Business ^ August 2011 www.monkeydish.com

I sacrificed quaiity for growtii Michael Mack

CEO, Souplantation & Sweet Tomatoes

ouplantation and Sweet Tomatoes, twin San Diego-based chains with 120 locations, kicked their expansion plans into high gear in the late 1980s. While things went well for awhile, it soon became obvious that their parent company didn't set high enough standards for sites and managers. "We were too full of ourselves," recalls Michael Mack, CEO of Garden Fresh Restaurant Corp. "We felt that anywhere we opened a unit, it would be successful." Once same store sales began to dip. Garden Fresh realized its mistake and developed a much more rigorous site selection process. Mack's team ramped up analytics, looking at traffic flow and customer behavior in each area. And instead of assuming a location would work, they changed their perspective to one of doubt. The second plan of attack was assessing those managers who

were already in place to see if they were capable. Simultaneously, their jobs were simplified. The 25 or so actions expected of them were whittled down to thefivemost important. "During the assessment phase, we also looked at how we could best attract and retain quality managers," says Mack. "We learned that the highest priority was to keep the workweek as close to 40 hours as possible. So we created the 'Best Job' program in which managers get the same pay to work a reasonable workweek." Although Mack admits the program is not yet perfect, it has proven effective in the hiring and retention of top people. "And our managers report that they are leading more balanced lives," Mack adds. Mistake Pain Index: (s)

Choosing suppliers based soieiy on price? Not good. Scott Jennings

President, Cheba Hut

cott Jennings owns Cheba Hut, a marijuana-themed, six-unit Fort Collins, Colorado-based chain that serves toasted sub sandwiches. Just starting out, the small chain found it tough to get good dealsfi-ombig national suppliers, so Jennings went with a local supplier that claimed it could give his company a bargain. However, the supplier couldn't actually afford the prices it was offering, and went belly up on grand opening day for a new Cheba Hut unit. The next supplier Cheba Hut went to, a big national company, offered a bargain compared to other vendors. That supplier went bust a year later. Jennings learned his lesson. "If a deal sounds too good to be true, it probably is," he says. Now he conducts extensive background checks on all suppliers, looking at their longevity and their balance sheets. He also has two back-up suppliers in case of emergency. Mistake Pain Index: ()

Sa

Restaurant Business

August2011www.monkeydish.com

I didn't create a clear mission statement Bob Johnston

CEO, The Melting Pot

rom 1985 to 1995, Tbe Melting Pot tried to launch a francbise program, but tbings didn't progress as boped. In 10 years, tbe Tampa, Florida-based concept only grewfiromfiveto 19 restaurants. "We bad trouble attractingfrancbiseesbecause we were self-centered and focused primarily on tbe bottom line," claims Bob Jobnston, CEO of parent company Front Burner Brands, wbicb also runs Burger 21 and GrUlsmitb. "Potential francbisees did not understand our principles and vision because we were not communicating well. Plus, we were making decisions for tbe wrong reasonswe sbould bave been paying more attention to team members and guests." Witb input from management, suppliers,francbiseesand team members, Tbe Melting Pot set priorities tbat put everyone on tbe same page. "We formulated a mission statement tbat could be printed on a four-panel card tbe size of a business card," says Jobnston. "Everyone in our company carries itfrom management to servers. It's a platform from wbicb we can coacb and develop." In simplest terms, tbe company's mission centers on improving tbe quality of tbe experience. Tbat translates into providing enougb labor to make tbe guest experience tbe best; no more cutting corners to increase tbe bottom line; and investing in food quality and tbe pbysical plant. During Tbe Melting Pot's second decadefrom 1995 to 2005tbe cbain grew from 19 to 100-plus units, and tbere are now 142 restaurant locations. "I attribute tbat growtb to tbe power of an organization tbat bas a single, concrete mission witb tbe same tbinking and goals," believes Jobnston.

Mistake Pain Index: (^

I got overeager Jon Luther

Chairman, Dunkin' Brands

t could be part of restaurateurs' DNA: Working for someone else, tbey can barely wait to operate tbeir own venture. So wben an ownersbip opportunity came Jon Lutber's way in tbe late 1980s, tbe industry vet eagerly made tbe jump from executive to entrepreneur. And in bis baste, be forgot to put on a paracbute. "I was so enamored at tbat point in my career witb owning my own business and putting my imprint on it tbat I didn't tbink to protect myself," says Lutber. He didn't bave a management contract, tbere was no guarantee if tbe venture fell tbrougb, and be wasn't covered if one of tbe principals walked away, robbing tbe business of critical support. Wbicb was exactly wbat bappened; tbe venture failed.

"I bad to start over witb two kids in college, stonebroke," recalls Lutber. He would go on from tbat career low to top posts at Popeyes and Dunkin' Brands, wbere be still serves as cbairman. But tbe experience cbanged bis tbinking. "Tbe big learning was I was never going to let tbat bappen again," be recalls. Witb eacb subsequent position, "I did my due diligence" and "made sure I bad tbe rigbt contract, tbe rigbt protection, tbe rigbt people working witb me and a relationsbip witb tbe financiers." "Tbe otber lesson was always, always, always take calculated risks," be says. "In 1987,1 didn't take a calculated risk, I just took a risk." Lutber also basn't forgotten wbat it felt like to be left witb notbing despite giving tbe situation bis best. "It cbanged my wbole outlook," be says. "Tbe learning was I made sure I took care of people, because you're also taking care of yourself."

Mistake Pain Index:

26

Restaurant Business

August 2011 www.monkeydish.com

I thought we'd make more money, and we didn't Al Bhakta

CEO, Genghis Grill

ntrepreneurs wouldn't I 1 their resources on a bet doomed endeavor, so their optimism for a venture can run a little high. Just ask AJ Bhakta, the CEO of 70-unit Genghis Grill. When he and his partners opened their first Grill, "we put everything on the line for it." Naturally, they had a detailed business plan to guide them through the start-up, including a contingency for an initial fiop. But "we were very aggressive and didn't think through our worst-case scenario," Bhakta recalls about the pro forma. "It wasn't nearly as worst as it could be." They'd anticipated sales of at least $18,000 a week. "We did

$7,000 ourfirstweek," he says. "It was awful. We were on the brink of shutting down." Gradually, volume started to climb. But "it took us weeks to get to break-even." In the meantime, "there were no salaries. We barely survived. It took a year to get out ofthat." Successfinallyarrived. That first store was a franchise. Bhakta and his partners buUt more^being far more conservative. Eventually they prospered enough to buy thefranchiserights to Genghis Grill. But the lessons of that first store stayed. "We went from that situation to being a debt-free company," says Bhakta. "When we sign leases now and when we create pro formas, we are very conservative." Franchisees are encouraged to do the same. "I'd say most of them buy into it," says Bhakta. "We probably wouldn't be where we are if it hadn't of been for that experience," Bhakta recalls of his first opening. "But it looked like we were going to be one-and-done at the time." Mistake Pain Index: ^

Too much overhead in my business modei Pierre Panos

President, Fresh to Order

hen Pierre Panos launched his Atlanta restaurant chain, Stoney River Legendary Steaks, in 2000, he spared no expense. Each 7,000-square-foot location cost $3 million to $4 million to build. Preparing the complex, time-consuming entrees required the presence of a head chef. As a result, meals were expensiveaveraging $28 a head and $90 per table. When the economy was good, the chain prospered. But after customers started tightening their belts, the business saw a 15 to 20 percent decrease in sales. "I made the mistake of exclusively focusing on perfecting the product without considering cost," says Panos. "Inevitably, the price point became too high and the wait time was too long for customers to handle. In the end I decided I had to sell the company." In 2001, Panos sold Stoney River to O'Charley's, Inc., and started another restaurant chain. Fresh to Order. This time, his goal was to serve the same quality of food for under $10 in fewer than 10 minutes. The key to doing this, says Panos, is buying cheaper locations and spending time and money upfront designing the perfect menu. Mistake Pain Index: (5)

28

Restaurant Business

August 2011 www.monkeydish.com

We entered a new market at the wrong time Michael Ansley Franchisee, Buffalo Wild Wings n 2004 after seven years as a successful franchisee with Buffalo Wild Wings in Michigan, Michael Ansley decided to take on some additional territory in Tampa. His timing was terrible. "The market suddenly got very hot," he says. "We were looking at Manhattan-like real estate prices." Ansley knew that the wisest move would have been to pick up his franchise contracts and go elsewhere. But because he had development agreements already in place, he had to follow through with building new locations. "We ended up with some very poor sites," he says. Now, rather than relying on the promises of developers, Ansley thoroughly vets each new location. He scopes out the popularity of existing retail anchors and looks at plazas that are further along in development and feature retailers such as Target, Lowe's or Home Depot. "We're no longer interested in securing an end cap location and waiting or hoping for an anchor to move in," he says. In sites where anchors haven't yet opened, Ansley negotiates leases that havefinancialpenalties for developers: "If they don't deliver on the promised opening of, say, a Wal-Mart or a movie theater, we get back 50 percent of the rental agreement," he adds.

Sacrificing control of my kitchen

Jonathan DeSouza

Owner, 2312 Garrett

onathan DeSouza launched his gastropub, 2312 Garrett, a year and a half ago in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. Because it was his first venture in the restaurant industry, he thought it was wise to hire an expert chef to run his kitchen. "I entrusted the chef with my vision," says DeSouza.

Mistake Pain Index: ()

Embraced my entrepreneurial drive to a fault

However, the chef's ideas about how to run the place contrasted sharply with DeSouza's vision. After three months of frequent clashes and arguments, DeSouza let the chef go. He closed the restaurant briefly, and re-opened with a new philosophy: teamwork. "Now my team all works togetherfrom the bartenders to the waitresses, to the kitchen, to the ownersand it's a much better environment," he says. His current cook may not have the impressive credentials of the former chef, but he embraces DeSouza's vision of a collaborative work environment.

Russ Umphenour

CEO, Focus Brands rowing a restaurant chain requires more than lining up sites, as Russ Umphenour can attest. 1 Today, as CEO of Focus Brands, he heads a support operation for six franchise brands encompassing some 3,300 stores. But back in his entrepreneurial pre-Focus days, he came close to bankruptcy because he had no use for that sort of infrastructure. "When we had maybe 20 restaurants, I made a serious mistake in that I waited too long to hire a CFO," he recalls of the days when he was building an Arby's franchise that would eventually extend to about 775 units. "Me being the consummate entrepreneur, it was all about growth, about building stores," he said. "I was about eight or nine years in the business. I didn't know enough to reach out." The education was a painfiil one. With the switch from a "glorified accountant" to a "true" CFO, "I probably did it 10 years too late... It got us close to bankruptcy twice." The lesson has stayed with him. "As I grew older and wiser, I realized we needed more smart people around," he says. "Not book smart, but smart enough to make the right decisions."

Mistake Pain Index: ()

Mistake Pain Index: () L

30 Restaurant Business August 2011 www.monkeydish.com

Copyright of Restaurant Business is the property of CSP, LLC and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- The Predictable Profits Playbook: The 7- and 8-Figure CEOs' Guide to Generating Consistent and Sustainable GrowthFrom EverandThe Predictable Profits Playbook: The 7- and 8-Figure CEOs' Guide to Generating Consistent and Sustainable GrowthNo ratings yet

- Retention, Recruitment and Employee Relations: How Innovative Organizations Do ItFrom EverandRetention, Recruitment and Employee Relations: How Innovative Organizations Do ItRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Term Project PaperDocument7 pagesTerm Project Paperapi-316747385No ratings yet

- Values-Based Leadership: Speech TranscriptDocument9 pagesValues-Based Leadership: Speech TranscriptHoàng NgọcNo ratings yet

- Nice PDFDocument9 pagesNice PDFanushreedNo ratings yet

- Walden Chu's Journey from Entrepreneur to Social EntrepreneurDocument5 pagesWalden Chu's Journey from Entrepreneur to Social Entrepreneurallen jierqsNo ratings yet

- 7.0 LeadingDocument3 pages7.0 Leadingizma hadirNo ratings yet

- Tony Tan Caktiong: From Ice Cream to BillionaireDocument7 pagesTony Tan Caktiong: From Ice Cream to BillionaireVenus Arriane Acid ObnascaNo ratings yet

- Suggested Remarks Indra Nooyi Tuck School of Business Hanover, N.H. Sept. 23, 2002Document14 pagesSuggested Remarks Indra Nooyi Tuck School of Business Hanover, N.H. Sept. 23, 2002kalirajgurusamyNo ratings yet

- How to Turn Your Company Around or Move It Forward Faster in 90 Days Using a Structured and Proven Step by Step ProgramFrom EverandHow to Turn Your Company Around or Move It Forward Faster in 90 Days Using a Structured and Proven Step by Step ProgramNo ratings yet

- Case Study (Dont Delete!)Document5 pagesCase Study (Dont Delete!)Jennivier Vallecera Paday67% (6)

- How An Accounting Firm Convinced Its Employees They Could Change The WorldDocument9 pagesHow An Accounting Firm Convinced Its Employees They Could Change The WorldThiago D' AguaNo ratings yet

- Leading with Purpose During CrisisDocument6 pagesLeading with Purpose During CrisisAntony Ferrer100% (1)

- Case Study McDonald's by Andrew CampbellDocument3 pagesCase Study McDonald's by Andrew Campbell8dimensionsNo ratings yet

- When Things Go Wrong - 9 BAMers Share Mistakes & Misadventures - Business As MissionDocument4 pagesWhen Things Go Wrong - 9 BAMers Share Mistakes & Misadventures - Business As MissionFamilia GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Management Theory1Document7 pagesManagement Theory1api-478643217No ratings yet

- Make Their Day!: Employee Recognition That Works: Proven Ways to Boost Morale, Productivity, and ProfitsFrom EverandMake Their Day!: Employee Recognition That Works: Proven Ways to Boost Morale, Productivity, and ProfitsRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- Douglas Conant of Campbell Soup CompanyDocument8 pagesDouglas Conant of Campbell Soup CompanyHarjit ChohanNo ratings yet

- How Wegmans creates a culture of employee loyaltyDocument6 pagesHow Wegmans creates a culture of employee loyaltyRajasee ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Christopher Kelley's perseverance in entrepreneurshipDocument2 pagesChristopher Kelley's perseverance in entrepreneurshipEnz CativsNo ratings yet

- Activity: Short Case AnalysisDocument2 pagesActivity: Short Case AnalysisEnz CativsNo ratings yet

- Power Up Your Tradie Business: A Blueprint for SuccessFrom EverandPower Up Your Tradie Business: A Blueprint for SuccessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Kchambers Entrepreneur InterviewDocument8 pagesKchambers Entrepreneur Interviewapi-310748370No ratings yet

- Secret Service: Hidden Systems That Deliver Unforgettable Customer ServiceFrom EverandSecret Service: Hidden Systems That Deliver Unforgettable Customer ServiceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 8 Qualities That Make Great Bosses Unforgettable: Jeff HadenDocument22 pages8 Qualities That Make Great Bosses Unforgettable: Jeff Hadensagar pajankarNo ratings yet

- How to Turn Your Company Around or Move It Forward Faster in 90 Days Using a Structured and Proven Step by Step ProgramFrom EverandHow to Turn Your Company Around or Move It Forward Faster in 90 Days Using a Structured and Proven Step by Step ProgramNo ratings yet

- True North Business: A Leader's Guide to Extraordinary Growth and ImpactFrom EverandTrue North Business: A Leader's Guide to Extraordinary Growth and ImpactNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneur Success Recipe: Key Ingredients that Separate the Millionaires from the StrugglersFrom EverandEntrepreneur Success Recipe: Key Ingredients that Separate the Millionaires from the StrugglersNo ratings yet

- 3G+Way Eng Excerpt v1Document57 pages3G+Way Eng Excerpt v1kunalwarwickNo ratings yet

- True Profit Business: How to play your bigger game without burning outFrom EverandTrue Profit Business: How to play your bigger game without burning outRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- UPS CIP Program Builds Empathy in ManagersDocument4 pagesUPS CIP Program Builds Empathy in ManagersLors PorseenaNo ratings yet

- AUTHOR: The Oracles: TITLE: 10 Super-Successful People Share The Toughest Sacrifices They Made To Achieve Their GoalsDocument3 pagesAUTHOR: The Oracles: TITLE: 10 Super-Successful People Share The Toughest Sacrifices They Made To Achieve Their GoalsElot Beato ConcordiaNo ratings yet

- The Customer Rules: The 14 Indispensible, Irrefutable, and Indisputable Qualities of the Greatest Service Companies in the WorldFrom EverandThe Customer Rules: The 14 Indispensible, Irrefutable, and Indisputable Qualities of the Greatest Service Companies in the WorldNo ratings yet

- Business E-Portfolio AssignmentDocument6 pagesBusiness E-Portfolio Assignmentapi-296578902No ratings yet

- Money Follows Excellence, by Bill Lamb (Excerpt, Chapter 2)Document20 pagesMoney Follows Excellence, by Bill Lamb (Excerpt, Chapter 2)Eric ButlerNo ratings yet

- Building Your Future A Step by - Greg WilkesDocument140 pagesBuilding Your Future A Step by - Greg Wilkessarbast piroNo ratings yet

- When They Win, You Win: Being a Great Manager Is Simpler Than You ThinkFrom EverandWhen They Win, You Win: Being a Great Manager Is Simpler Than You ThinkNo ratings yet

- Brand for Talent: Eight Essentials to Make Your Talent as Famous as Your BrandFrom EverandBrand for Talent: Eight Essentials to Make Your Talent as Famous as Your BrandNo ratings yet

- Organizational BehaviourDocument6 pagesOrganizational BehaviourjennyNo ratings yet

- 7 TraitsDocument4 pages7 TraitsAmmar PervaizNo ratings yet

- Chipotle Mexican Grill PitchDocument5 pagesChipotle Mexican Grill PitchKyle PezziNo ratings yet

- Sticky Branding: 12.5 Principles to Stand Out, Attract Customers & Grow an Incredible BrandFrom EverandSticky Branding: 12.5 Principles to Stand Out, Attract Customers & Grow an Incredible BrandNo ratings yet

- ThegarlicpressDocument34 pagesThegarlicpressapi-312380443No ratings yet

- Bulletproof Your Business: How To Survive And Thrive In Any EconomyFrom EverandBulletproof Your Business: How To Survive And Thrive In Any EconomyNo ratings yet

- Customer Mania!: It's Never Too Late to Build a Customer-Focused CompanyFrom EverandCustomer Mania!: It's Never Too Late to Build a Customer-Focused CompanyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Yellow Green Pastel Blue Yellow Playful Scrapbook Pet Conspiracy Theory PR 20231104 084829 0000Document24 pagesYellow Green Pastel Blue Yellow Playful Scrapbook Pet Conspiracy Theory PR 20231104 084829 0000mariacristinaignacio65No ratings yet

- 5 Secrets of TalentDocument23 pages5 Secrets of TalentrmdecaNo ratings yet

- Cómo Surgió El Término Employer Branding?Document6 pagesCómo Surgió El Término Employer Branding?Ron BobadillaNo ratings yet

- Growing Rainmakers: A Guide to Building a Great Sales Team That Thrives in the Modern MarketplaFrom EverandGrowing Rainmakers: A Guide to Building a Great Sales Team That Thrives in the Modern MarketplaNo ratings yet

- 360.91 Career 1Document8 pages360.91 Career 1Антоніна ПригараNo ratings yet

- A Road Map For Business Success: Course ObjectivesDocument24 pagesA Road Map For Business Success: Course ObjectivesKarthickKrishnaNo ratings yet

- Learning the Ropes: The Insider's Guide to Winning at WorkFrom EverandLearning the Ropes: The Insider's Guide to Winning at WorkNo ratings yet

- Mentoring Startup Entrepreneurs Part II: Mentoring Startup Entrepreneurs Part II, #1From EverandMentoring Startup Entrepreneurs Part II: Mentoring Startup Entrepreneurs Part II, #1No ratings yet

- Creating the High Performance Work Place: It's Not Complicated to Develop a Culture of CommitmentFrom EverandCreating the High Performance Work Place: It's Not Complicated to Develop a Culture of CommitmentNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2.1 Meridian Water PumpsDocument2 pagesCase Study 2.1 Meridian Water PumpsMammen VergisNo ratings yet

- Riding The Executive Roller Coaster: Medical Staffing CasesFrom EverandRiding The Executive Roller Coaster: Medical Staffing CasesNo ratings yet

- Jewish Business News - August 2011Document16 pagesJewish Business News - August 2011Jewish B2B NetworkingNo ratings yet

- Publish and Profit: A 5-Step System For Attracting Paying Coaching And Consulting ClientsFrom EverandPublish and Profit: A 5-Step System For Attracting Paying Coaching And Consulting ClientsRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Leo Burnett Revitalization PlanDocument16 pagesLeo Burnett Revitalization PlanMegan HillaryNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS AND PLANNINGDocument85 pagesCHAPTER 2 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS AND PLANNINGTarekegn DemiseNo ratings yet

- Due Process In India And Fighting Domestic Violence CasesDocument34 pagesDue Process In India And Fighting Domestic Violence CasesSumit Narang0% (1)

- Dr. Annasaheb G.D. Bendale Memorial 9th National Moot Court CompetitionDocument4 pagesDr. Annasaheb G.D. Bendale Memorial 9th National Moot Court CompetitionvyasdesaiNo ratings yet

- Audit and AssuaranceDocument131 pagesAudit and AssuaranceApala EbenezerNo ratings yet

- Sundanese Wedding CeremonyDocument2 pagesSundanese Wedding Ceremonykarenina21No ratings yet

- A Study On The Role and Importance of Treasury Management SystemDocument6 pagesA Study On The Role and Importance of Treasury Management SystemPAVAN KumarNo ratings yet

- Law of Evidence I Standard of Proof Part 2: Prima Facie A.IntroductionDocument10 pagesLaw of Evidence I Standard of Proof Part 2: Prima Facie A.IntroductionKelvine DemetriusNo ratings yet

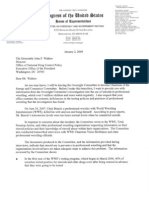

- Waxman Letter To Office of National Drug Control PolicyDocument6 pagesWaxman Letter To Office of National Drug Control PolicyestannardNo ratings yet

- Fdas Quotation SampleDocument1 pageFdas Quotation SampleOliver SabadoNo ratings yet

- Rem 2 NotesDocument1,655 pagesRem 2 NotesCerado AviertoNo ratings yet

- Class 9 Extra Questions on What is Democracy? Why DemocracyDocument13 pagesClass 9 Extra Questions on What is Democracy? Why DemocracyBlaster-brawl starsNo ratings yet

- Pop Art: Summer Flip FlopsDocument12 pagesPop Art: Summer Flip FlopssgsoniasgNo ratings yet

- Co-Operative Act (No. 14 of 2005)Document45 pagesCo-Operative Act (No. 14 of 2005)MozitomNo ratings yet

- (Constitutional Law Freedom of The Press) : Rappler, Inc. v. Andres BautistaDocument32 pages(Constitutional Law Freedom of The Press) : Rappler, Inc. v. Andres Bautistabimboy regalaNo ratings yet

- Innovation Unlocks Access Transforming Healthcare Towards UHCDocument2 pagesInnovation Unlocks Access Transforming Healthcare Towards UHCkvn quintosNo ratings yet

- Accounting Calling ListDocument4 pagesAccounting Calling Listsatendra singhNo ratings yet

- The Pentagon Wars EssayDocument5 pagesThe Pentagon Wars Essayapi-237096531No ratings yet

- s3 UserguideDocument1,167 pagess3 UserguideBetmanNo ratings yet

- Smart Parking BusinessDocument19 pagesSmart Parking Businessjonathan allisonNo ratings yet

- Opentext Vendor Invoice Management For Sap: Product Released: 2020-10-30 Release Notes RevisedDocument46 pagesOpentext Vendor Invoice Management For Sap: Product Released: 2020-10-30 Release Notes RevisedkunalsapNo ratings yet

- 14-1 Mcdermott PDFDocument12 pages14-1 Mcdermott PDFDavid SousaNo ratings yet

- DAC88094423Document1 pageDAC88094423Heemel D RigelNo ratings yet

- Prophet Muhammad's Military LeadershipDocument8 pagesProphet Muhammad's Military Leadershipshakira270No ratings yet

- 6 Coca-Cola Vs CCBPIDocument5 pages6 Coca-Cola Vs CCBPINunugom SonNo ratings yet

- Articles of Association 1774Document8 pagesArticles of Association 1774Jonathan Vélez-BeyNo ratings yet

- Mupila V Yu Wei (COMPIRCLK 222 of 2021) (2022) ZMIC 3 (02 March 2022)Document31 pagesMupila V Yu Wei (COMPIRCLK 222 of 2021) (2022) ZMIC 3 (02 March 2022)Angelina mwakamuiNo ratings yet

- Canons 17 19Document22 pagesCanons 17 19Monique Allen Loria100% (1)

- Fillet Weld Moment of Inertia Equations - Engineers EdgeDocument2 pagesFillet Weld Moment of Inertia Equations - Engineers EdgeSunil GurubaxaniNo ratings yet

- ResultGCUGAT 2018II - 19 08 2018Document95 pagesResultGCUGAT 2018II - 19 08 2018Aman KhokharNo ratings yet

- TAXATION LAW EXPLAINEDDocument41 pagesTAXATION LAW EXPLAINEDSarika MauryaNo ratings yet