Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Status of Water Resources in West Bengal

Uploaded by

Debashish RoyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Status of Water Resources in West Bengal

Uploaded by

Debashish RoyCopyright:

Available Formats

The Status of Water Resources in West Bengal (A Brief Report) By- Dr.

Kalyan Rudra 10jan

2009

Introduction The world is fast running out of fresh water, our demand for this blue gold is increasing at a faster pace

water with passing time and thousand more people are compelled to survive in a water-stressed condition. One-half and two-thirds of the global population will be put to severe fresh water crisis within next quarter century, if we do not change our present wasteful mode of water- use (Barlow and Clarke, 2003). The corporate sector treats water as a commodity. It is human need, not right they proclaim. The idea of selling water to the highest bidder denies the basic fact that water constitutes the fundamental component to all life forms and cannot be therefore, treated as a saleable commodity. It is an integral component of all ecological and societal processes Our planet is apparently rich in water but about 97.5 per cent of its water resource is saline as such unsuitable for drinking or irrigation. The volume of fresh water is only 2.5 percent of the total and that too is not readily accessible. About 68.7 per cent of fresh water is piled up in high latitude and altitude as snow and glaciers and 29.9 per cent is remaining as ground water and soil moisture. The global hydrological cycle operates through successive stages involving the evaporation-condensationprecipitation of 568000 km3 of water annually. The continents of the Earth receive 42750 km3 of water as precipitation, of which 32 percent falls on Asia (Gleick, 1993).. India gets 4000 km3 of water (0.70 per cent of the global or 9.36 per cent of the Asian precipitation) annually as precipitation but our country renders home to about 16 percent of worlds population on 2.45 per cent of the terrestrial surface ( NCIWRD, 1999):. The total rainfall, if evenly spread, can submerge the country with a sheet of water having depth of 1.20m. The distribution of this natural resource in India is spatially and temporally so uneven that hydrological extremes of flood and drought are annual events in some parts or the other. When Cherapunji receives more than 11000mm of rain annually, large parts of Rajasthan

receive less than 200mm of rainfall. The south-west monsoon virtually generates more than 80 percent of annual precipitation in this country and that pours during the months of June-September. But a single cloud burst over a place can generate more than 60 percent of annual rain within a span of just 48 hours. The most of monsoon rain in this country if clubbed together virtually occurs over a matter of 100 hours or so (Agarwal , Narain and Khurana, 2001). The management of spatially uneven and temporally skewed rain-water in India is the most serious challenge for the watermanagers of this

River Hugali (Ganga) at Howrah Bridge, Kolkata. country. Water Resource in West Bengal: West Bengal covers 2.7 per cent of the national territory and renders home to 8 per cent of the Indian population. The State is endowed with 7.5 per cent of the water resource of the country and that is becoming increasingly scarce with the uncontrolled growth of population, expansion of irrigation network and developmental needs. The Bengal Delta, which was described as areas of excess water in the colonial document, now suffers from acute dearth of water during lean months. The spatial and temporal variability of rain within the State causes the twin menaces of flood and drought. Both the flood and drought isopleths are expanding with time in spite of ever-increasing investment in water management. The navigation even in the southern tidal regime has become an extremely difficult task for the country boats that require minimum draft. The Kolkata port continues to face the brunt of siltation even after the artificial induction of water from the Farakka Barrage. The rivers flowing through this State have altered their courses appreciably during last two centuries and many of them have been wiped out from the map. Water Resource: Availability Vs Requirement The Irrigation and Waterways Department (1987) of the Government of West Bengal made an assessment of the available water resource within the State in 1987. The Expert committee made a detailed exploration in the 26 river basins and stated that though the surface water in this state is estimated to be 13.29 Mham, only about 40 percent of it is utilisable. On the other hand, the available ground water though being 1.46 Mham only, is totally utilisable. The Central Ground Water Board estimated the annual available ground water as1.76 m.ham while the Irrigation Commission of Government of India put it as 2.38 m.ham. (Goswami, 1995, 2002). Goswami and Basu (1992) however, presented a more detailed account of the Water Resources of West Bengal and this is the most widely accepted report on the issue. The availability of water resource within this State is

spatially and temporally uneven. The one-dimensional supply-side management of water involving an almost blind faith on large dams and long distance transfer of water proved futile due to evaporation and transit losses. The water efficiency in dam-canal networks of India was estimated to be 30-40 per cent only (NCIWRD, 1999). In fact present water crisis in West Bengal is largely due to misuse or abuse of water. The greatest foul is being played in the agricultural sector the largest consumer, since the introduction of high yielding paddy in early 1970s. To realise this, one must have a comprehensive understanding about the supply-demand scenario of water in this State.

Availability of Water in West Bengal Surface and Ground water (Mham) Surface water Ground water Total 14.75 6.77 1.46 1.46 13.29 5.31 Availability Utilisable

Source: State Irrigation Department The utilisable surface water (5.31Mham) in this State is less than 40 per cent of the available surface water (13.29 Mham). One major challenge of water management is to reduce this crucial gap. If utilisable water can be enhanced to 60 per cent of the available water by creation of more storage, additional 1.20 Mham of water will be available for our use. The irrigation sector is the largest consumer of water followed by the inland navigation sector. The official projection evinces that demand of water for agriculture would shoot up to 7.71 and 10.98 Mham in the years 2011 and 2025

respectively and those are more than available water for use by all sectors. So creation of additional storage and demand side management are dual challenges of present water management. Requirement of Water in West Bengal (Mham) Sector Agriculture Domestic Industry Power (Thermal) Inland Navigation Forestry Ecology, Environment and Others 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.01 0.01 0.01 3.63 3.63 3.63 0.31 0.26 0.38 0.59 0.26 0.28 0.38 5.38 7.71 10.98 2000 2011 2025

Total (Mham) Source: State Irrigation Department The State can distinctly be divided into three geographical units viz. North Bengal, Western Rarh and Plains to the east of Bhagirathi. About 63 per cent of the water resource of the entire State is carried by eight basins of North Bengal while the Rarh and eastern plains are endowed each with 22 per cent and 15 per cent of water respectively. The eight river basins of North Bengal drain the southern slope of the Himalaya and carry about 98679 MCM of surface and 9130MCM of ground water annually. Monsoon rain is the source of most of the water in the rivers, which is concentrated within three months. The conservation or storage of water in this tract is difficult because the upper catchment of most of the rivers lie in Sikkim or Bhutan beyond the territorial boundary of West Bengal. The potential risk of siesmicity in the Himalayan terrain and high sediment load in rivers make building of dams ecologically as well as economically unsound. In fact, the huge water resource of North Bengal enters Bangladesh without being intercepted. However, there exists ample scope of rainwater harvesting but no such project has yet been undertaken. The discharge hydrographs of the rivers in North Bengal are so skewed temporally, that flood becomes a recurring phenomenon. The reservoirs of south Bengal are located either along the western border of the State or beyond that i.e. within the territory of the adjacent State of Jharkhand. The reservoirs of Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC), Massanjore, Hinglow and Kanshabati have lost their live storage capacity substantially due to siltation. The transit loss of water during the long distance transfer of water may be more than 60 per cent in addition to evaporation loss. Thus the large dams can only effectively meet merely 2.44 per cent of the demand of water in the agricultural sector (see Box 1). Box 1

10.85

13.02

16.60

ROLE OF LARGE DAMS IN WEST BENGAL Total Storage Capacity at initial stage: 413.91 X 107 cu.m. Present Storage Capacity after 20 per cent reduction of capacity due to siltation: 313.13 X 107 cu.m.

Available water after evaporation and transit loss of about 60 per cent: 132.45 X 107 cubic metre. Present annual demand for irrigation: 5380 X 107 cu.m. The reservoirs meet only 2.44 per cent of the demand. Since the supply of water is naturally constrained and demand is increasing in leaps and bounds, the gap in between is extending with time. GROWTH OF POPULATION AND DECLINING PER CAPITA WATER YEAR (in Crore) (in cu.m) POPULATION PER CAPITA WATER

1951 1961 3.49 1940

2.63

2574

1971 1981 1991 2001 8.02 844 6.80 996 5.46 1240

4.43

1528

2011

9.40

720

Water Requirement Vs Supply. Year 2000 2011 2025 Source: Compiled from data of State Irrigation Department The decades of 1950 and 1960 witnessed large scale dam-building either beyond the western border of the State or just along the boundary and even today we have no sustainable system to conserve the rain-water that falls within the geographical territory of West Bengal. The massive capitalintensive engineering interventions into the fluvial system during the post-independence era was guided by a reductionist engineering logic of remaking the Nature for meeting increasing and indiscriminate needs of population and economy. The engineers denied the basic ecological tenets and laws governing the fluvial regime and consequently the projects have not fared well in delivering due benefits and have instead been subject to serious and prolonged controversy over grim social, economic and environmental repercussions. Since 1970 there was the beginning of over-exploitation of the ground water often beyond the naturally replenishable limit. This was directly related to the introduction of high-yielding but waterintensive seeds that replaced the traditional ones. Now more than 0.60 millions of shallow and more than 5000 deep tube wells are operating in the agricultural fields of the State. Ground Water exploitation: 16.60 59% 13.02 48% 10.85 38% Water Requirement (Mham) Deficit

Comparison of figures of 1st.,2nd., & 3rd. minor irrigation census.

Sl .no. 19861987 1995 2001 1987 1995 2001 1987 1995 2001 19942000198619942000198619942000-

Type

No. of Schemes

CCA in ha.

GCA in ha.

1.

DW

63387

55983

39387

31984

24386

27961

44054

39879

45411

2.

STW

368316

504638

603667

624507

1015476

1169906

994475

1543586

2002210

3.

DTW

3122

4039

5139

121689

154065

183162

197650

258192

308731

4.

SF

70820

66454

53781

357212

381412

329399

427724

459040

470680

5.

SL

205471

83645

107595

545654

352936

385431

695186

496682

600161

Total

711116

714759

809559

1681046

1928275

2095849

2359089

2797379

3427193

Note: CCA- Culturable Command Area. GCA- Gross Irrigation Potential Created. DW-Dug-well, STWShallow Tubewell, DTW- Deep Tubewell, SF- Surface Flow Scheme, SL-Surface Lift Scheme. ( Source: Report of the Third Minor Irrigation Census( 2003), Govt. of west Bengal.) WATER REQUIREMENT FOR SOME MAJOR CROPS IN WEST BENGAL

Crop Requirement Season (in Kg/ha. excluding cultivation. tonnes) Litre/kg utilisable (000ha.) rainfall. (in mm) (m.ha.m.) Intensity 000 season under Utilized

Sowing

Harvesting

Water-

Area

Water

Yield

Production

Water-

Aus (Paddy) October

April

August-

300-450

402.55

0.15

2091

841.83

2152

Aman Mid July (Paddy) December

Mid

June

November-

300-600

4211.56

1.90

2374

9999.96

4423

Boro (Paddy)

December

April-May

1400-1600

1454.99

2.18

3334

4418.88

4944

Wheat

November

March

400-450

434.00

0.18

2215

961.53

1919

Potato March

November

February-

400-450

299.82

0.13

26090

7822.36

164

Jute October

April

August-

200

651.81

0.13

13556

8836.17

295

Pulses

Oilseed

November

February

250-300

604.15

0.17

816

493.04

3370

TOTAL

4.84

NB: 1. Aus, Aman and Boro are three types of Paddy grown in West Bengal. 2. Total water Requirement of Aus, Aman and Jute including utilisable rain water being 450, 900-1200 and 350-450 mm respectively. Menace of Arsenic: The ever-increasing exploitation of ground-water has already brought forth the problem of arsenic poisoning in 75 administrative blocks belonging to eight districts of lower Gangetic plain, where occurrence of arsenic beyond permissible limit (i.e. more than 0.05 to 3.24mg/l) in ground water are mostly confined to shallow aquifer zones within 20-100 feet below ground level. About 26 million people are now at risk and even the city of Kolkata is not out of the danger zone. There are conflicting views about the possible cause of this menace. A group scientist opines that arsenic is released by the oxidation of pyrite or arsenopyrite following the lowering of ground water table. The other view is that arsenic is released due to desorption from or reductive dissolution of ferric oxyhydroxides in reducing aquifer environment (KMPC,2006). However, there is consensus among the scientists that the challenge should be met by using surface water as far as possible. The recharging of ground-water by rain water harvesting seems to be the best option. The ground-water in Nalhati and Rampurhat blocks of Birbhum district, on the other hand, was found contaminated with fluoride. While the maximum permissible limit of fluoride in ground water is recommended to be 1.50mg/l, water quality in large parts of Birbhum is reportedly alarming (CGWB, 2001). Impairing the Eco-Hydrology: The ever increasing dependence on ground water for irrigation and drinking led to the decay and abandonment of age-old surface water management system of Bengal. The Zamidars (Landlords),Rarh tract excavated many ponds or built check dams to conserve the rainwater during monsoon months. The defection of this eco-friendly system began with the expansion of arable land, depletion of forest cover and expansion of railways. especially in western The hydrological equilibrium of the Bengal delta was largely impaired during 18th and 19th Century when the Zamindars and colonial rulers started to construct linear embankments along the bank of deltaic rivers with a view to control flood. This was a direct intervention into the fluvial regime that interrupted the annual distribution of sediment over the flood plain. The philosophy of water management was guided by a reductionist and rather simplified notion of achieving total freedom from flood by channelising the monsoon flow within embankments. This concept fails to take cognisance of the natural ecological functions that are equally important for the maintenance of the ecology and economy of the floodplains(McCully,2007). The fluvial system continuously transfers fluid and solids and this function is not only restricted within its channel but covers the wide floodplain where silt is deposited during the annual floods. The monsoon freshet flushes out sediment load from the channel and spills over the adjoining plain. The delta or floodplain building is thus intimately related to this ecological function of distribution of sediment load over the floodplains. The jacketing of the river with embankment interrupts the vital exchange of water and sediments between the channel and the floodplain, ultimately leading to the decay of drainage channel. So embankments were

rightly judged as satanic chains by Willcocks (1930) . Majumdar (1941) was more critical about this scientifically unapt way of achieving freedom from flood and wisely opined construction of flood control embankments a flood-controlling measure would be like mortgaging the future generations to derive some temporary benefits for the present generations. .But the State Irrigation Department chooses to remain in dark and continues to be guided by the colonial legacy of arresting the dynamic equilibrium of tropical monsoon rivers and ultimately causing degeneration of the drainage system. The Ganga divides the State of West Bengal in to two unequal halves, popularly known as the North and South Bengal. The former is constituted of six districts namely Cochbihar, Jalpaiguri, Darjeeling, Uttar Dinajpur, Dakshin Dinajpur and Malda. These districts cover together an area of about 21763 sq. kms, which are about 25 per cent of the total geographical area of West Bengal. The population living in this geographical unit is estimated to be 15 million (2000) .The floods in North Bengal districts is almost a yearly event. This hydrological phenomenon frequently threatens lives and livelihood of a large number of people. The damages ensuing to annual flood ravages are spiraling up, year-to-year in spite of the independence, no holistic flood management has been adopted. The Governments attitude remains inclined toward a purely engineering-oriented measure characterised by a high degree of adhocism. The official data on flood are generally full of discrepancies, unreliability and lackadaisical disinformation. The north Bengal plain offers natural outlet to the huge rain and snowmelt water of the Ganga-Brahmaputra basin, which encompasses an area of about 1.50 million square km. The Himalayan rivers become abruptly sluggish while approaching the plains. The rivers, which were enclosed within high bank or natural levees, enjoy the opportunity of free swing. The sudden loss of energy due to declining slope compels the rivers to deposit the sediments within their bed and thereby cause reduction of the capacity of rivers to hold water. The massive landslide and slope failures in the Himalaya often create temporary dams, which block the course of the rivers. Water continues to accumulate behind the natural dam until it is overtopped or breached when huge water rushes downstream and causes total devastation. In October 1968, Tista breached a series of such debris-dams and flooded the Jalpaiguri town. Being located along foot of the fragile Himalayan range, the North Bengal plain has become extremely flood prone. Agriculture is the largest consumer of water. If we continue in the business as usual mode, by pursuing the present irrigation type and choice of crops, the demand of water will exceed the available water in no distant period. Proposed Interlinking of Rivers: The National water Policy was adopted on the 1st.April, 2002. The new policy proposed to divide the country into several water-zones with a view to transferring water from so called excess to deficit areas (NWP, 2002). The concept is launched with the pious intension of ensuring food security of the country.But there is enough scope to challenge the scientific validity of the project (Bandyopadhyay and Perveen,2004).The concept of excess or deficit in the ecosystem is an unmixed myth since all components are perfectly balanced in Nature. The Government of India does not take into account the basic ecological principle and ventures to withdraw a substantial portion of water from Brahmaputra-Ganga and Mahanadi basins. The ever-expanding expenditure for flood control. Even after five long decades of

excavation of 192 km.long Manas-Sankosh-Teesta-Ganga (MSTG) link will lead to the destruction of 2133 ha.of forest area in addition to 2194 ha.of agricultural land, settlement area and tea estate. The 394 km long Ganga-Damodar- Subarnarekha (GDS) link canal will gobble 8300 ha.of fertile land and forest cover (Sarkar,2004).

The project does not take into account the ecological security and the delicate hydrological balance of the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta. Nor any heed was paid to the demand of huge population living in largest delta of the World. Even the question of Indo-Bangaldesh relationship over the sharing of water of Ganga, Brahmaputra and Tista was denied. Since 54 rivers are trans-boundary in nature and flows into Bangladesh from West Bengal, the Government of India should cohere with our neighboring State on the issue of water management.

The withdrawal of sweet water from Ganga-Brahmaputra basin may allow the saline water wedge to ingress further inland causing a serious ecological imbalance in the delta. Still Government of India adheres to the most expensive and optimistic water-management project the human civilization has ever witnessed. The long distance transfer of water would need to negotiate the topographic barriers and the power required for the purpose may be more than the project is expected to generate. It is learnt from the experience of large dam projects that the crucial gap between storage and actually utilised water must be reduced by shifting the place of conservation within or near the agricultural field. The only option to achieve this target is decentralised rainwater harvesting which can be attained by community participation and with the aid of low capital investment ventures. Such bottom-up options would be farmer-centered, eco-friendly and cost-effective. The major shift of paradigm should be reduction of over-dependence on ground water and that is to be utilised within the rechargeable limit. The water-intensive crops are to be replaced with drought-resistant crops as far as practicable. Finally, the community should continue to be the custodian of water. Drinking Water: The National Water Policy (2002) declared that ensuring the supply of drinking water should be the first priority of the Government. No village in India receives such scanty rain that we cannot quench the thirst of people. The per capita requirement of water per day is estimated to be 135 litres. But many citizens, especially in rural areas are denied of right to water. The average annual rainfall of the State is 1750mm, which largely runs off to the sea. The mission of the Government relating to drinking water supply during post-independence was largely dedicated towards the urban centres, while the rural areas remained neglected. The people of Purulia,Bankua and West Medinipur face serious water crisis during every summer. The Kolkata Metropolitan Area covering 1785 sq.km. consists of three corporations, 38 Municipalities,70 non-municipal Urban units, 14 outgrowth centres and 422 rural units. The population in this area was 14.78 million in 2001 and demand of water was 492.87 million gallon per day. The demand includes 30 million floating population who congregate into the city every day for job or business. The seven pumping stations extract 451.50 million gallon of

water per day from the Hugli river. The actual gap between demand and supply of water is much wider because the transmission distribution loss is more than 30%. This leads to everincreasing exploitation of ground water. Polluting the Ganga: The British had a clear vision on the role of Ganga and other rivers in this country. They realized that urban and industrial wastewater must not be poured into the river that was the only lifeline of the entire region. They excavated east flowing canals through the city of Kolkata to divert the wastewater into the natural wetlands on the eastern fringes. The East Kolkata Wetlands not only act as the reservoir but also as locations for the recovery of precious resources through a natural process. The absence of necessary regulations in independent India led to further pollution of the sacred river. The River Goddess was the helpless victim of indiscriminate dumping of urban and industrial effluents. In West Bengal the magnitude was alarming. Other industrial and urban centers on both sides of the river treated the river as a convenient outlet for polluted wastewater. The river began to gasp for life! Fish was scarce. Even the delicious Hilsa, so dear to Bengali cuisine, fast became an expensive thing of the past. The Gangetic dolphins became a rare and endangered species! The devotee, who takes holy bath in the sacred waters, are hardly aware of its terrifying chemical properties! The Ministry of Environment and Forests of the Government of India have now specified the quality of water that should flow into the river. When the dissolved oxygen is equal to or more than 5 milligrams per litre, the bio-chemical oxygen demand is 3 milligrams per litre and when the maximum probable number of coliform organisms is 500 per 100millilitres, the water is said to be safe for bathing. The truth is alarming. But the flowing water is not like that. In many different ways we also contribute generously to the acts of polluting the river Ganga. The narrative of the River Goddess had changed drastically into the call for emergency measures. The Ministry of Environment and Forest of the Government of India envisaged a plan to save the river from further damage in February 1985. It was a project for the people of India. The initial thrust was immediate reduction in the domestic pollution load in 25 Class I riverside towns in West Bengal, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, of these, 15 were located in West Bengal alone. The 1984 comprehensive survey of the Ganga basin by the Central Pollution Control Board resulted in the Action Plan. The survey indicated that out of the total measurable point sources of pollution, 75% was on account of municipal sewage from towns located along the banks of the river and the remaining 25% was on account of industrial effluents. In 1984, an estimated 4186 million litres of wastewater was discharged daily into the Ganga along its entire course. West Bengal contributed 868 million litres every day, with its Bio Chemical Oxygen Demand or BOD load was 119.53 tonnes, while Chemical Oxygen Demand, or COD, load was 330.96 tonnes, and Suspended Solid, or SS, load was 405.99 tonnes.With only 7% of the Ganga Basin located in West Bengal, it used to contribute about 21% of the total wastewater.The domestic wastewater discharge was 338.8 million litres per day. Daily, the BOD was 22.24, COD stood at 101.21, and SS at 81.49 tonnes. The Story of the First Phase of the Gangs Action Plan began with improvement of the water quality up to acceptable levels by intercepting the pollution load reaching the river. The

Monitoring Committee recast the objective of the First Phase to restoring water quality up to the designated best bathing class. In 1984, dissolved oxygen in the river-water that flowed along Kolkata ranged from 5.4 to 7.7 milligrams per litre. Recent investigation reveals that it now ranges from 5.4 to 9.8. The Biochemical oxygen demand has declined from 1.5 to 3 in 1984 to less than1to3 milligrams per litre. The maximum probable number of coliform count, which ranged between 50,000 to more than nine lacs two decades ago, is today reduced to the 23,000 to 1,50,000 range. Even the quantity of dissolved solids had reduced. These successes have been achieved through several schemes. Theoretically, West Bengals 21 treatment plants now purify 371.60 million litres of water every day this is about 42 % of the total treatment facility created during the First Phase of the Ganga Action Plan. But many untreated sewage outlets still continue join the river. Many industries pollute the river flouting the norms imposed upon them. The restoration of water quality in the river is certainly a peoples programme, achievable only through collective responsibility. Large numbers of riparian communities and individuals, more than just Government officials, must act if the river has to be saved. Only People can protect holy river. But we must act fast, before its too late. By- Prof. Kalyan Rudra. Reference: 1. Agarwal, A. Narain, S. and Khurana, I. (2001): Making Water Everybodys Business. Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi.pp.i-xxxi. 2. Agarwal, A. and Narain, S. (1996): Flood, Flood plains and Environmental Myths. Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi. pp 95-125. 3. Bandyopadhyay, J. and Perveen, S. (2004): Interlinking of Rivers in India: Assessing the Justifications. In Interlinking of Rivers in India: Myths and Reality. Ed. By S.K. Bhattacharya, A. Biswas and K. Rudra. The Institution of Engineers (India), West Bengal State Centre.pp.838. 4. Barlow, M and Clarke,T ( 2003): Blue Gold. Left world Books, New Delhi,pp.3-49. 5. CGWB, ( 2001).Ground Water Year Book of West Bengal(1999-2000).pp.11-12 6. Gleick, P.H. (1993). Water in Crisis.OUP, New York pp.3-10 7. Goswami, A.B. (2002) Hydrological Status of West Bengal. In Changing Environmental Scenario of the Indian Subcontinent. Ed. By S.R. Basu.ACB Publication, Kolkata. pp.299-314). 8. Goswami,A.B (1995): A Critical Study of Water Resources of West Bengal. Unpublished Ph.D.. thesis,Jadavpur University,pp.57-65 9. Goswami,A.B. and Basu,B. (1992): Water Resources of West Bengal. School of Water ResourceEngineering, Jadavpur University.pp.1-49. 10. I W D, G.o W. B. (1987): Report of Expert Committee on Irrigation.pp.1-27 11. K.M.D.A.(2006): Story of a River: A Film on Ganga Action Plan in West Bengal.

12. Kolkata Metropolitan Planning Committee(2006): Five Year Development Plan(2003-2008) for Area.p.2.86 13. McCully Patrick (2007): Before the Deluge/ Coping with Flood in Changing Climate.Dams, Rivers and People 2007 (An IRN Report) pp. 2-13 14. NCIWRD,Govt. of India ( 1999): Integrated Water resource Development / A Plan for Action .New Delhi.pp. i-xvii 15. NCIWRD,Govt. of India ( 1999): Integrated Water resource Development / A Plan for Action .New Delhi.p.33 16. NWP,(2002): GoI, , 18p. 17. Majumdar, S.C. Rivers of Bengal (1941) Reprinted by West Bengal state Gazetteers Department. p. 19. 18. Master Plan for Water Supply within Kolkata Metropolitan Area 2001-2025.pp7-93 19. Mishra, D.K.(2002): Living with the Politics of Floods. Peoples Science Institute, Dehradun.pp.35-68 15. Rudra, K. (2004): The Interlinking of Rivers: A Misconceived Plan of Water Management in India. In River Linking: A Millennium Folly? Ed. By Medha Patkar, Published by NAPM and Initiative. Mumbai, pp.55-70 20. Sarkar, B.(2004): Interlinking of Rivers in India- A Brief Review. In Interlinking of Rivers in India: Myths and Reality. Ed. By S.K. Bhattacharya, A. Biswas and K. Rudra. The Institution of Engineers (India), West Bengal State Centre.pp.117-124. 21. Shiva, V. (2002); Water Wars: Privatisation, Pollution and Profit. IRP, New Delhi.159p. 17.Shiva, V. Bhar,R. H. Jafri, A.H. Jalees, K. (2002): Corporate Hijack of Water. Navadanya, New Delhi.P.3. 22. 17.Willcocks, W. (1930) Ancient System of Irrigation in Bengal Reprinted by West Bengal state Gazetteers Department. p129-30. By- Dr. Kalyan Rudra Environment,Wetland, Urban Amenities and Heritage within Kolkata Metropolitan

You might also like

- Water Scarcity and Security in IndiaDocument20 pagesWater Scarcity and Security in IndiaHimanshu DobariyaNo ratings yet

- India's Green Revolution ExaminedDocument13 pagesIndia's Green Revolution ExaminedKabirNo ratings yet

- The Energy Crisis in the Philippines: A Project Economics ThesisDocument15 pagesThe Energy Crisis in the Philippines: A Project Economics ThesisireadstuffNo ratings yet

- Ancient AdministrationsDocument23 pagesAncient AdministrationsANANDUNo ratings yet

- Scheduled Tribes Education in India: Issues and ChallengesDocument10 pagesScheduled Tribes Education in India: Issues and ChallengesAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Market Entry to India for Renewable Energy VenturesDocument19 pagesMarket Entry to India for Renewable Energy VenturesMuhammad FahimNo ratings yet

- Indian History and CultureDocument80 pagesIndian History and CultureTanishq SinghNo ratings yet

- Land Reform and Agrarian Change in India and Pakistan Since 1947 IDocument24 pagesLand Reform and Agrarian Change in India and Pakistan Since 1947 IUsman AhmadNo ratings yet

- Kaveri River DisputeDocument14 pagesKaveri River DisputeKanhaiya ParwaniNo ratings yet

- Federalism in CanadaDocument11 pagesFederalism in Canadaonganya100% (2)

- 01 Indian Mineral Industry &national EconomyDocument22 pages01 Indian Mineral Industry &national Economymujib uddin siddiquiNo ratings yet

- Indian Polity by NIOSDocument400 pagesIndian Polity by NIOSKanakath Ajith100% (2)

- Koodankulam Anti-Nuclear Movement: A Struggle For Alternative Development?Document17 pagesKoodankulam Anti-Nuclear Movement: A Struggle For Alternative Development?Rajiv PonniahNo ratings yet

- Science and Technology in IndiaDocument231 pagesScience and Technology in IndiaNijam NagoorNo ratings yet

- Indifference Curve AnalysisDocument36 pagesIndifference Curve AnalysisChitra GangwaniNo ratings yet

- Narmada Bachao Andolan: India's powerful mass movement against damsDocument8 pagesNarmada Bachao Andolan: India's powerful mass movement against damstitiksha KumarNo ratings yet

- Population Composition and Sex Ratios ExplainedDocument20 pagesPopulation Composition and Sex Ratios ExplainedAlga BijuNo ratings yet

- Jharkhand 04092012Document51 pagesJharkhand 04092012Ram NamburiNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Climate Change To AgricultureDocument6 pagesThe Effect of Climate Change To AgricultureMarichu DelimaNo ratings yet

- Government and Politics in North East India: An In-Depth GuideDocument99 pagesGovernment and Politics in North East India: An In-Depth GuideImti LemturNo ratings yet

- Drainage System of IndiaDocument16 pagesDrainage System of IndiaAju 99Gaming100% (1)

- Concept of IsostasyDocument7 pagesConcept of IsostasySunny Duggal100% (1)

- Agrarian Crisis and Farmer SuicidesDocument38 pagesAgrarian Crisis and Farmer SuicidesbtnaveenkumarNo ratings yet

- Indian Society 12th NCERT SociologyDocument33 pagesIndian Society 12th NCERT SociologyAyush JaiwalNo ratings yet

- Tribal DevelopmentDocument6 pagesTribal DevelopmentDivyaNo ratings yet

- The Indus Water Treaty Between India and PakistanDocument4 pagesThe Indus Water Treaty Between India and Pakistanharoon ahmed waraich100% (2)

- Student Movement in IndiaDocument1 pageStudent Movement in IndiaMonish NagarNo ratings yet

- Global PovertyDocument7 pagesGlobal PovertySagarNo ratings yet

- Land Reforms - MrunalDocument118 pagesLand Reforms - MrunalcerafimNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument23 pagesEconomicsImran Ahmed KhanNo ratings yet

- 12 Five Year Plan of IndiaDocument20 pages12 Five Year Plan of IndiaAppan Kandala VasudevacharyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Coronavirus on Indian Economy: Supply Chain, Tourism, and GrowthDocument6 pagesImpact of Coronavirus on Indian Economy: Supply Chain, Tourism, and GrowthMayank Kumar50% (2)

- Green Revolution in IndiaDocument1 pageGreen Revolution in IndiaVinod BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Cast in IndiaDocument30 pagesChapter 3 Cast in IndiaFarman AliNo ratings yet

- Saleena PatraDocument37 pagesSaleena PatraSwarnaprabha PanigrahyNo ratings yet

- 9 Most Essential Causes of Rural Unemployment in IndiaDocument10 pages9 Most Essential Causes of Rural Unemployment in IndiaAmit VijayNo ratings yet

- Equilibrium in Economics: A Project Report OnDocument18 pagesEquilibrium in Economics: A Project Report OnOnindya MitraNo ratings yet

- Janapadas & MahajanapadasDocument20 pagesJanapadas & MahajanapadasSmita Chandra100% (2)

- Agro Climatic Zones of India - UPSCDocument12 pagesAgro Climatic Zones of India - UPSCSUMIT KUMARNo ratings yet

- Indian Peasant Movement: A Social RevolutionDocument9 pagesIndian Peasant Movement: A Social RevolutionSUBHASISH DASNo ratings yet

- Changing Land Relations and Culture in Northeast India's Tribal CommunitiesDocument11 pagesChanging Land Relations and Culture in Northeast India's Tribal Communitiespkirály_11No ratings yet

- The Effect of Climate Change On The EconomyDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Climate Change On The EconomyjobNo ratings yet

- Indian Council Act, 1919Document36 pagesIndian Council Act, 1919Ankit Anand100% (1)

- History Final ProjectDocument22 pagesHistory Final ProjectAnanya ShuklaNo ratings yet

- History Material First SemesterDocument93 pagesHistory Material First SemesterAishani ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court's Controversial Judgment on India's River Linking ProjectDocument8 pagesSupreme Court's Controversial Judgment on India's River Linking ProjectSukiran DavuluriNo ratings yet

- Narmada Bachao Andolan Is Social Movement Consisting of Tribal PeopleDocument5 pagesNarmada Bachao Andolan Is Social Movement Consisting of Tribal PeopleJoash JamesNo ratings yet

- Ken Betwa Linking PlanDocument103 pagesKen Betwa Linking PlanfeelfreetodropinNo ratings yet

- Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission-A Critique-2006-1-FDocument2 pagesJawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission-A Critique-2006-1-FnaveengargnsNo ratings yet

- Gandhian Thought's Relevance to India's Economic PolicyDocument8 pagesGandhian Thought's Relevance to India's Economic Policyraghvendra shrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Energy PyramidDocument10 pagesEnergy PyramidganeshmamidiNo ratings yet

- Harvesting Despair 00 161-169 Francine Frankel PDFDocument9 pagesHarvesting Despair 00 161-169 Francine Frankel PDFparulNo ratings yet

- Indo-China Relations Post-Cold WarDocument10 pagesIndo-China Relations Post-Cold Warsakshi rathiNo ratings yet

- The Diverse Cultures of IndiaDocument4 pagesThe Diverse Cultures of Indiakrushna vaidyaNo ratings yet

- Act Made by BritishersDocument11 pagesAct Made by BritishersMonika VermaNo ratings yet

- Illegal Migration Into Assam Magnitude Causes andDocument46 pagesIllegal Migration Into Assam Magnitude Causes andManan MehraNo ratings yet

- Essay: TOPIC:-Water Resource Utilisation and Irrigation Development in IndiaDocument9 pagesEssay: TOPIC:-Water Resource Utilisation and Irrigation Development in IndiaSumit SinghNo ratings yet

- M 6 L 02Document28 pagesM 6 L 02neha161857697No ratings yet

- Surface Water ResourcesDocument11 pagesSurface Water ResourcesKunal YadavNo ratings yet

- Review of KWDT II Final ReportDocument63 pagesReview of KWDT II Final ReportN. SasidharNo ratings yet

- Question BookDocument1 pageQuestion BookDebashish RoyNo ratings yet

- Scalene Triangle Area CalculationsDocument1 pageScalene Triangle Area CalculationsDebashish RoyNo ratings yet

- Leadership 47Document1 pageLeadership 47Tophani SinghNo ratings yet

- Toxicity of Indian VegetablesDocument1 pageToxicity of Indian VegetablesDebashish RoyNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument6 pagesDownloadRavindra Shamrao UikeyNo ratings yet

- First 90 DaysDocument1 pageFirst 90 DaysDebashish RoyNo ratings yet

- Exposure 2010 Entry FormDocument3 pagesExposure 2010 Entry FormDebashish RoyNo ratings yet

- Cl142 Es PPT 3 Water PollutionDocument30 pagesCl142 Es PPT 3 Water Pollutionthor odinsonNo ratings yet

- Anthropogenic Activities and Water Quality in Estero de Binondo, ManilaDocument92 pagesAnthropogenic Activities and Water Quality in Estero de Binondo, ManilaClayd Genesis CapadaNo ratings yet

- Sewerage ListingDocument52 pagesSewerage ListingplyanaNo ratings yet

- TurbidexDocument2 pagesTurbidexJANCARLONo ratings yet

- Sewage Treatment PlantDocument16 pagesSewage Treatment PlantSrinivasa NadgoudaNo ratings yet

- Sludge Management Master Plan For A Highly Urbanized MetroDocument1 pageSludge Management Master Plan For A Highly Urbanized MetroMARIANNo ratings yet

- Rainwater Harvesting 101Document55 pagesRainwater Harvesting 101Art Del R Salonga100% (1)

- 23 - Rajasthan MPR Dec 2020Document65 pages23 - Rajasthan MPR Dec 2020Ashish DongreNo ratings yet

- Strategi Pengendalian Pencemaran Air Sungai Gude Ploso Di Kabupaten Jombang Lilik PurwatiDocument16 pagesStrategi Pengendalian Pencemaran Air Sungai Gude Ploso Di Kabupaten Jombang Lilik PurwatiAnugrah TaufiqurrachmanNo ratings yet

- Man1 6 2017 SeptageDocument9 pagesMan1 6 2017 SeptageEuwzzelle Barpinkxz Lim TalisicNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Heavy Metals Contamination in Drinking Water of Garmian Region, Kurdistan, Iraq PDFDocument14 pagesAssessment of Heavy Metals Contamination in Drinking Water of Garmian Region, Kurdistan, Iraq PDFAzad Hama AliNo ratings yet

- Abstract - Industrial Wastewater Management in Indian ContextDocument1 pageAbstract - Industrial Wastewater Management in Indian ContextRaviIdhayachanderNo ratings yet

- Agrochemicals and Their Effect On The EcosystemDocument11 pagesAgrochemicals and Their Effect On The Ecosystempuremaths14042021No ratings yet

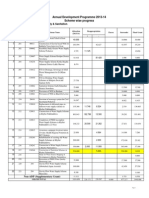

- Sector: Drinking Water Supply & Sanitation: Annual Development Programme 2013-14 Scheme Wise ProgressDocument1 pageSector: Drinking Water Supply & Sanitation: Annual Development Programme 2013-14 Scheme Wise ProgressFazal Ahmad MarwatNo ratings yet

- Waste Water TreatmentDocument57 pagesWaste Water TreatmentVishal PatelNo ratings yet

- 503-Article Text-1428-1-10-20211210 - 2Document10 pages503-Article Text-1428-1-10-20211210 - 2yamar2000No ratings yet

- Agriculture Grade 7 TestsDocument19 pagesAgriculture Grade 7 TestsLungile ChuduNo ratings yet

- GOVENDER Et Al. Contribution of Water Pollution From Inadequate Sanitation and Housing Quality. 2011Document6 pagesGOVENDER Et Al. Contribution of Water Pollution From Inadequate Sanitation and Housing Quality. 2011Ananda BritoNo ratings yet

- Grease Trap DesignDocument2 pagesGrease Trap DesigndcsamaraweeraNo ratings yet

- Jurnal: Daur LingkunganDocument10 pagesJurnal: Daur LingkunganAhmad RifaiNo ratings yet

- SWRO Pretreatment: Conventional vs MF/UFDocument38 pagesSWRO Pretreatment: Conventional vs MF/UFDudy FredyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 WastewaterDocument115 pagesChapter 3 WastewaterNur Iffatin100% (1)

- Industrial Pollution Abatement Tutorial QuestionsDocument3 pagesIndustrial Pollution Abatement Tutorial Questionssudhanshu shekharNo ratings yet

- AURAEA3003 Monitor Environmental and Sustainability Best Practice in The Automotive Mechanical IndustryDocument11 pagesAURAEA3003 Monitor Environmental and Sustainability Best Practice in The Automotive Mechanical Industryera teknikNo ratings yet

- Water Act SummaryDocument9 pagesWater Act SummaryanonymousNo ratings yet

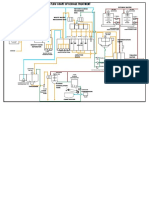

- Flow Chart Sewage TreatmentDocument2 pagesFlow Chart Sewage TreatmentapriNo ratings yet

- Occupational Safety and Health Simplified For The Chemical Industry by Frank R. SpellmanDocument205 pagesOccupational Safety and Health Simplified For The Chemical Industry by Frank R. SpellmandeepthiNo ratings yet

- Thesis Title Proposal 1Document14 pagesThesis Title Proposal 1Warner LeanoNo ratings yet

- Handover For Erection - DASHBOARD As Per Acceleration Prog - Internal - 2021 - 10 - 19Document1 pageHandover For Erection - DASHBOARD As Per Acceleration Prog - Internal - 2021 - 10 - 19Sakura ShigaNo ratings yet

- Water Purification Sheet 1Document1 pageWater Purification Sheet 1api-527998485No ratings yet