Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2006 Loeys, J., Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum

Uploaded by

Arthur FournierOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2006 Loeys, J., Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum

Uploaded by

Arthur FournierCopyright:

Available Formats

Market Strategy J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd.

London February 8, 2006

Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum

We propose an innovative strategy that achieves high

returns with low risk by exploiting momentum in relative returns across a wide set of asset classes.

The strategy simply overweights the asset classes that have

performed best over the past 6 months.

It thus differs from existing momentum strategies that focus

on mispricing within single asset classes.

The strategy has been robust with the same risk-adjusted

performance in bull and bear markets.

Risk-adjusted returns were highest in periods of high

volatility, high dispersion and low market returns.

JPMorgan markets this strategy through a structured

product: Investible Global Asset Rotator (IGAR).

Profiting from momentum across asset classes

The asset allocation decision is probably the most important contributor to the performance of an investors overall portfolio. Most investors base tactical asset allocation decisions on considerations of value. In this paper, we propose a simple method based instead on momentum. Specifically, we exploit the momentum in the relative return across a wide set of asset classes. In its most basic form, the strategy invests each 6 months in 5 asset classes, out of a possible 10, choosing those asset classes with the highest returns over the past 6 months. Across the broad set of asset classes we consider, this strategy added on average an extra 4.0% return p.a. to investing equally across all 10 asset classes over the past 11 years.

Ruy M. Ribeiro*

(44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com

Jan Loeys

(44-20) 7325-5473 jan.loeys@jpmorgan.com J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd.

Contents

Profiting from momentum with asset classes Why momentum? High returns, simple and transactable Choice of momentum rules Performance Robustness Long-short and short only strategies Conclusions and caveats 1 3 4 5 6 7 13 14

We are grateful to Eynour Boutia, Declan Canavan, Ioannis Katsikas, Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, Peter Rappoport, Nicolas Robin, Yasemin Saltuk and Mathew Webb for their valuable comments and discussion. Remaining errors are our own. The certifying analyst is indicated by an *. See last page for analyst certification and important legal and regulatory disclosures.

www.morganmarkets.com

INVESTMENT STRATEGIES: NO. 14

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Chart 1: A Simple Momentum Strategy 6-month/6-month rule

Asset Classes US Equity, International Equity, Global Bonds, Emerging Market Bonds, High Grade, High Yield, Real Estate, Commodities, Hedge Funds, and Currency

Invest in Winning Asset Classes

in absolute performance in one single asset class at a time, using rules such as moving-average filters. Momentum vs. Value. This strategy is purely based on momentum, but could also be combined with value strategies with the potential to deliver even higher returns. This will be investigated in later work. The main contribution of our analysis is the extension of standard and well-known momentum rules to the relative return on multiple asset classes. Most of the rules we analyse here have been proposed by both academics and practitioners for individual securities in contributions that even predate the beginning of our sample. One related application is the work on equity momentum strategies. The equity momentum strategy relies on the idea that stocks that were recent winners will tend to perform better in the near future than recent losers. These rules divide all the stocks in groups (for example, 10 equallyweighted portfolios) based on their recent performance using the past 3 to 12 months. After ranking and grouping the individual stocks, the investment rule overweights recent winners and underweights losers. Here we follow the same approach, but apply across different asset classes. The performance of both strategies share a surprising resemblance. Our analysis shows that momentum exists not only in the relative return of individual securities, but also in that of different asset classes. Since the seminal paper by Jagadeesh and Titman1, an extensive literature has confirmed the existence of momentum in equities and other markets. Our own analysis confirms that momentum still exists in equities in many different forms. We extend the analysis in a new direction with similar success. We believe that the same economic reasons that justify momentum in equities can explain momentum across different markets. This paper is organized as follows. First, we discuss why we should expect to see momentum in asset classes. Then, we deduce how achieving a strategy with a high return to

Rank 10 asset classes by past performance Invest in Top 5 only Equally-Weighted Portfolio

Now

6 months later

Compute past 6-month returns

Source: JPMorgan

Rebalance only 6 months later

This asset allocation strategy is a medium-term, tactical, rulebased macro-allocation across a diverse set of asset classes, based on the momentum in the relative return of 10 different asset classes. Medium-term tactical as opposed to strategic. We do not address long-term benchmark selection, but instead focus on tactical deviations from a broad benchmark, on a medium-term (6-month) horizon. Rule-based, as opposed to discretionary. The strategy is a simple, deterministic rule on how to switch dynamically from one asset class to another. Macro asset classes. We find the strategy works best by switching across very different types of asset classes, such as equities, bonds, commodities, real estate, etc.., rather than related asset classes, such as different equity sectors, national bond markets, or individual securities. This is because greater similarity increases the importance of value indicators and thus reduces the potential for trend dispersion in performance. Cross-market momentum. We switch from one asset class to another using past performance as sole criterion. Since we overweight the recent top performing asset classes, we are exploiting momentum in relative performance of one asset class against another. We find this cross-market momentum strategy performs better than basic trend-following strategies that focus on momentum

2

Jagadeesh, N and S. Titman, Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency, Journal of Finance, March 1993

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com Jan Loeys (44-20) 7325-5473 jan.loeys@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Chart 2. Underreaction and Overreaction price

160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0

Source: JPMorgan

Chart 3. Momentum and Value price

Price

160 140 120 Momentum

Value becomes dominant

Underreaction

Overreaction Value

Value

100 80 60 40 20 0

Source: JPMorgan

Price

risk, that is simple and transactable requires focusing on a wide set of asset classes represented by well-known indices and funds. Third, we analyse a simple version of a crossmarket momentum strategy (see description in Chart 1). Fourth, we check the robustness of these results by varying the specification of the strategy in many different ways. The overall conclusion is that it is profitable to incorporate momentum into the asset allocation decision.

Why momentum?

Momentum is an empirical phenomenon that contradicts market efficiency. In an efficient market, it should not be possible to build a profitable trading strategy using only information about past returns without moving into riskier assets. Even well-known guardians of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, such as Eugene Fama, recognize the possibility that momentum profits could be due to a market inefficiency2. There could be other explanations, even based on a rational framework, and there are a lot of theories that try to explain momentum. We focus on behavioural finance arguments, as we consider them more convincing. Most theories created to explain the existence of momentum come from the equities literature. But they can be applied without much modification to a wider set of asset classes. Two basic behaviour biases are commonly suggested as reasons for momentum: underreaction and overreaction to information.

2 Fama, E. and K.French, Multifactor Explanations of Asset Pricing Anomalies, Journal of Finance, January 1996

In the underreaction case, investors are unable to process available information in a timely fashion. Thus, security prices underreact to new information. In that case, prices will slowly adjust in the direction of intrinsic value, producing short-term trends. For example, new information arrives that tells investors that fundamentals are better than expected. But investors are suspicious and do not adjust their expectations fully: Prices move less than fundamentals would imply. Consequently, prices will only slowly absorb the positive past information. The overreaction story is also based on other investors cognitive biases. Investors learn that fundamentals are better than expected. Most of the investors adjust their expectations fully, but some of the investors extrapolate this positive news into the future. Prices increase as fundamentals would predict, but they continue the upward move beyond fundamentals because of extrapolation or even trend-following behaviour. Both behavioural biases will make prices deviate persistently from intrinsic value. However, they will also reinforce the profitability of value strategies. The overreaction story implies that prices will eventually adjust to the new information. Chart 2 presents an example where both underreaction and overreaction take place. First, investors underreact to the unobservable change in intrinsic value. But later some investors overreact to the same change, creating an additional trend. Both behavioural biases generate momentum. Moreover, overreaction will also create value opportunities as reversals will most probably occur.

3

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Chart 3 shows a simple case of mean reversion around a stable fair value. Extreme deviations trigger the contrarian value signal, but even in this value-driven market, momentum exists as the market swings from expensive to cheap, and back again. We believe that one reason for momentum to be a strong driver of the relative return across assets is that flows tend to be strongly affected by the past performance of assets, especially when there is no clear consensus on how to assess relative value. Within a particular asset class it will be easier to compare value, and flows will be less driven by past performance. Previous research has shown that investors tend to chase winners. With most investors fully invested, such flows will come out of relative losers, thus creating greater momentum in relative than in absolute returns.3 One obvious questions is why we do not analyse flows directly. The answer is very simple: we are not interested in past flows but in future flows. Past flows are not good forecasting variables for future flows while empirical evidence does show that past performance does forecast future flows. Therefore, past performance is a better proxy for future flows than past flows.

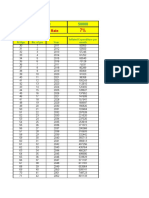

2. transactability, which requires focusing on tradable indices or funds; and 3. robustness, which requires simplicity. (1) High Sharpe ratio and diversity. A high return to risk taking requires (1) focusing on the relative returns that will be most susceptible to momentum rather than value considerations, and (2) diversifying sufficiently across a series of unrelated momentum trades. Both of these requirements, in our mind, imply choosing a diverse set of asset classes. The more diverse, the greater the difficulty that investors will have in assessing relative value across assets classes, and thus the higher the chance they will rely on recent performance to judge future returns. When assets classes are easily comparable, such as different parts of a yield curve, then relative value will be a much more important driver of returns. The greater the diversity of asset classes, the weaker the value force will be, and the stronger the momentum force can be instead. The diversity of asset classes at the same time promotes diversification of exposures, thus reducing the denominator of the Sharpe ratio. The broad set of global asset classes can be divided into four groups: equities; bonds; credit; and alternative investments. For the equities group, we choose a US equity index (S&P 500) and an international index that excludes the US (MSCI World ex US). The bond group is limited to our global bond index hedged against currency risk (JPMorgans GBI). The credit group is represented by an emerging markets bond index (JPMorgans EMBIG), a high yield bond index (Lehman Brothers) and a high-grade bond index (Lehman Brothers)4. The alternative investment segment consists of real estate (NAREIT index), commodities (GSCI), emerging market currencies (JPMorgans ELMI), and hedge funds (HFRI composite). All returns are in US dollars. The sample is based on monthly returns from January 1994 to December 2005. Chart 4 shows the Sharpe ratio of each one of these asset classes and for the equally-weighted portfolio, an investment with constant and equal weights in all ten asset classes. Table 1 provides additional sample statistics. All these numbers are based on data since July 1994, which is our comparison period, since the momentum strategy requires a few months for the initial ranking.

4 We choose Lehmans indices instead of our own as they have a longer data history, which is necessary for one of our robustness checks with older data.

High returns, simple, and transactable

The strategy is based on an allocation decision within a diversified set of asset classes. It is thus a tactical asset allocation rule based on momentum. The first challenge we face is how we should structure this strategy and how we choose asset classes. To be interesting to investors, the strategy should focus on 1. a high return to risk (high Sharpe ratio), which requires a large and diverse set of asset classes;

3 Our momentum strategy is designed to anticipate these flows and exploit behavioural biases. Some of the selected asset classes may, however, not be clearly affected by flows or the direction of the effect could even go the other way. This is true in the case of hedge funds. The common belief is that flows into hedge funds hurt their performance as strategies become overcrowded. Nethertheless, there are other reasons to see trends in hedge fund performance. First, they are exposed to standard risk premia, since they tend to have betas against traditional asset classes. Therefore, flows into standard asset classes will also affect hedge funds. Second, their performance can be related to other risk measures such as volatility. If volatility varies in a persistent way, hedge fund performance will also have a persistent component.

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com Jan Loeys (44-20) 7325-5473 jan.loeys@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Chart 4. Sharpe Ratios Asset Classes

1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 MSCI World ex US Real Estate - NAREIT 0.4 0.2 0.0 Equally-Weighted

High Grade

High Yield

S&P 500

GSCI

ELMI

EMBI

HFRI

(3) Robustness and simplicity. There are many ways we can translate momentum into a feasible strategy. To avoid complexity and the risk of data mining, we focus on the most basic rules. Leveraging off the extensive equities literature, which focuses on winners versus losers, we divide the 10 asset classes into two groups based on the recent performance: top 5 absolute returns (winners), and bottom 5 (losers). The portfolio buys only the top 5 performers over the recent past, equally weighted. A number of more complicated schemes were investigated, but this did not improve performance. These alternative approaches, some of which we will discuss later, include a trading strategy where we go long the top 5 and short the bottom 5. In effect, our going long the top 5 is equal to being long all 10 (the global benchmark) and adding on a trading strategy of being long top 5 versus bottom 5 (Chart 20 to be discussed later on). Most investors cannot go short these asset classes so we focus on the long-only strategy. The strategy uses absolute returns as the single ranking criterion. We investigated using risk-adjusted returns (Sharpe ratios) as ranking criteria, but this did not improve performance and only added complexity. Similarly, we know that it is easy to improve performance by empirically optimising the weights on the different asset classes, but experience tells us this type of data mining tends to hurt outof-sample performance.

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

Table 1. Sample Statistics for Asset Classes

Average Excess Returns EMBI Real Estate NAREIT S&P 500 HFRI GSCI ELMI GBI MSCI World ex US High Grade High Yield Equally-Weighted Cash (30-day Bill - Yield) 11.5% 9.5% 7.7% 7.4% 6.9% 4.0% 4.0% 3.3% 3.2% 3.1% 6.2% 4.2% Standard Deviation 14.6% 13.2% 14.9% 7.1% 20.4% 6.3% 3.9% 14.8% 5.3% 10.0% 6.8% 0.6%

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

Some of these indices do not correspond to standard definitions of asset classes. Our choices are proxies for the possible types of risk and return that global investors can face. All of them are strategies that are long potentially different types of risk premia. Hedge funds are not clearly an asset class, but are investment strategies that generate returns with more complex exposures to standard asset classes using derivatives, short-selling and leverage. The same claim can be made regarding some of the other choices for asset classes, but they are all exposed to some form of risk premia. (2) Transactability. We want to guarantee that the strategy could be easily implemented without high transaction and replication costs. Therefore, we want to use simple, well-known, and potentially tradeable indices with sufficiently long histories. Where they are not directly tradeable, funds exist that closely track these indices.

GBI

Choice of Momentum Rules

In order to exploit momentum, it is necessary to choose both a ranking period and the rebalancing frequency. The ranking period is the number of past months used to compute the recent performance and, thus, to rank the assets. The rebalancing frequency is the number of times a year that the portfolio is rebalanced. Given that our strategy tries to exploit flows, our ranking period should be not longer than the typical investment horizon that investors hold. Previous research has shown that investors horizons tend to be around one year. We find indeed that a ranking period of around 6 months performs best, with returns falling off fast when we use a ranking period longer than a year.

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Table 2. Sharpe and Information Ratios for Optimal Strategy Benchmark Risk-Free Rate (Sharpe Ratio) Equally-weighted Portfolio Average Portfolio Table 3. Alpha relative to alternative benchmarks Alpha (based on regressions) Model Benchmark S&P 500 Alpha (t-statistic) 7.45% (4.13) 4.04% (3.44) 3.63% (3.19) Information Ratio 1.32 0.94 0.71

Chart 5. Sharpe Ratios

1.4 1.2 1.0 Cross-Market Momentum 0.8 MSCI World ex US 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 Real Estate - NAREIT

Equally-Weighted

High Grade

High Yield

S&P 500

EMBI

GSCI

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

Equally-weighted Portfolio

Performance

Tables 2, 3 and 4 show the basic statistics of the optimal strategy, which is the one that maximizes the Sharpe ratio of the portfolio. In the optimal strategy, we use the past six months of returns for the purposes of ranking asset classes. Coincidentally, the rebalancing period is also every six months. The basic statistics are very strong with a total annual return of 14.52% with a volatility of only 7.41%, where we take into account a potential monthly 8bp transaction cost. The most important characteristics are: 1. high Sharpe ratio; 2. stable and high alpha; and 3. well-balanced exposure to all asset classes. The momentum strategy has a much higher Sharpe ratio than any of the individual components or the equallyweighted portfolio, as we can see in Chart 5. The outperformance against the equally-weighted portfolio is important for two reasons. First, the equally-weighted portfolio is the obvious candidate for a passive benchmark6. Second, this passive benchmark has twice the number of underlying asset classes. The volatility of the equallyweighted benchmark is only slightly lower than the crossmarket momentum strategy, while returns are much lower. Additionally, the strategy outperforms the equally-weighted basket in almost all one-year horizons. Chart 6 shows the plot of the cumulative returns of the cross-market momentum strategy, along with the underlying asset classes and the equally-weighted portfolio. We can clearly see the high

Average Portfolio Table 4. Basic Statistics Statistic Average Excess Return Total Return - Geometric Average Standard Deviation Max (monthly) Min (monthly)

Source: JPMorgan

Value 9.69% 14.53% 7.41% 5.83% -9.03%

The rebalancing frequency does not have to match the ranking period. We could rebalance each month, but this will be too expensive given the diverse set of assets we use. We find that rebalancing each 6 months performs best, even before taking account of transaction costs. We could also consider a framework where we rebalance a fraction of the portfolio every month (analysed later on)5.

5 In terms of other choices, we could have lagged the ranking period by one month in order to facilitate the actual rebalancing of the portfolio, but this change does not impact performance. This is also a common procedure in the analysis of equity momentum for reasons other than implementation. In the equities case, there is empirical evidence of short-term reversals (one month or less), mostly due to bid-ask spreads and liquidity effects. These are not important issues in the case of momentum with asset classes. We report different risk-adjusted measures of the performance of this strategy in order to show that this strategy outperforms different passive benchmarks. For instance, we show the information ratio against two possible benchmarks: the equallyweighted portfolio; and the average portfolio. In both cases, the alpha and information ratio are economically significant. We also compute alpha against different benchmarks using regression analysis besides the common practice of subtracting the benchmark return. The alphas are statistically significant in all reported cases.

HFRI

ELMI

GBI

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com Jan Loeys (44-20) 7325-5473 jan.loeys@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Chart 6. Cumulative Performance Cumulative return of 100 invested in June 1994

600 500 400 S&P500 300 200 100 0 Jun-94 GBI Cross-Market Momentum

Chart 7. Betas with respect to S&P 500

1.2 1.0 0.8 Equally-weighted portfolio Real Estate - NAREIT

HFRI

0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 -0.2 S&P 500 MSCI World ex US

Cross-Market Momentum

High Grade

High Yield

EMBI

GSCI

GBI 10% 4%

HFRI

ELMI

Equally-weighted portfolio

Jun-96

Jun-98

Jun-00

Jun-02

Jun-04

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

Chart 8. Average Portfolio Weights

Real Estate - NAREIT 14% S&P 500 12%

return, the low volatility and the persistence in outperformance. The profitability of the strategy is not due only to a few good months or years, as the strategy shows a high and stable alpha.

HFRI

In general, the strategy is not highly exposed to any one of the asset classes, even though profitability of this strategy comes from the ability to switch betas. For instance, chart 6 shows the beta with respect to the S&P 500. It is quite low if we take into account that we have two underlying equity indices. It is lower than HFRI, the hedge fund index, for example. Despite the fact that the exposure to equity can be from time to time close to 40%, the sensitivity to equities is not high on average. Chart 7 shows the time-series average of portfolio weights exposure of the long-only strategy. We can see that this average portfolio is well-balanced, since it is very close to an equally-weighted portfolio. We observe that on average the weights are very close to 10%, despite the fact that at each point in time the weights can only be 0% or 20%, and even higher due to infrequent rebalancing. The highest average weight is 13%. Another important issue is the fluctuation in volatility. The expected volatility fluctuates over time, since we change allocations to assets with different volatilities and correlation structures. However, fluctuations in volatility are not very economically significant. The maximum estimated volatility stays around 13% a year. An investor with target volatility exposures can address this question by combining this strategy with an investment in the risk-free asset in order to maintain a constant volatility.

13% GSCI MSCI World ex US 9% High Grade 7% ELMI 6% EMBI 14% 11% High Yield

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

Robustness

We will now see that the optimal rule above is only one of the many momentum rules that work, providing us with confidence that the idea makes sense and that the good results do not arise from pure luck. There is no theory that can tell us exactly when we should reallocate the portfolio or how many months should be used to rank asset classes. Hence, we report the performance of the optimal strategy, but also for other similar strategies. It is an easy task to create complicated rules that generate high alphas with past data. It is a lot more difficult to do the same with simple strategies that are robust to changes in parameters, such as ranking and rebalancing period. In the next sub-sections, the analysis focuses on the robustness of the results to variations in the rules.

7

GBI

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Table 5. Robustness to Changes in Rule

Formation (Ranking) 5 6 7 8 9 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 Rebalancing 6 6 6 6 6 4 5 6 7 8 6 6 6 6 6 Assets 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 1 2 3 4 5 Average Exc. Return 8.16% 9.69% 8.09% 8.35% 8.07% 9.69% 8.66% 9.69% 8.55% 9.44% 9.21% 10.55% 10.21% 9.06% 9.69% Standard Deviation 7.58% 7.41% 7.29% 7.31% 7.77% 7.47% 7.42% 7.41% 7.79% 7.59% 17.30% 11.77% 9.08% 7.84% 7.41% Sharpe Ratio 1.0763 1.3071 1.1108 1.1419 1.0376 1.2972 1.1667 1.3071 1.0971 1.2433 0.5327 0.8963 1.1245 1.155 1.3071

Alpha (EW) 2.35% 4.04% 2.66% 2.94% 2.14% 3.95% 3.06% 4.04% 2.57% 3.59% 1.46% 3.04% 4.01% 3.47% 4.04%

t-stat 2.1707 3.44 2.2265 2.4651 1.7231 3.3828 2.5509 3.44 2.1266 3.075 0.3195 1.215 2.2614 2.4143 3.44

Beta (S&P500) 0.3087 0.2919 0.2732 0.2762 0.3042 0.279 0.2934 0.2919 0.3074 0.2942 0.2918 0.3307 0.3005 0.2787 0.2919

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

Table 6. Sub-Sample Analysis

Sample First Half (1994-1999) Second Half (1999-2005) Average Exc. Return 9.72% 9.64% Standard Deviation 8.29% 6.25% Sharpe Ratio 1.17 1.54

Alpha (SPX) 3.30% 5.12%

t-stat 2.16 2.95

Beta (SPX) 0.49 0.16

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

The following robustness checks are considered in the analysis: 1. changes to ranking period, rebalancing frequency and number of assets: We increase and decrease the number of months used to compute recent performance and the rebalancing frequency. We also change the number of assets. 2. exclude and add asset classes: We consider the effect of excluding some of the asset classes, showing that the results do not rely on any of the included assets classes. 3. partial rebalancing: We implement other complicated, but perhaps more robust, rules such as monthly partial rebalancing schemes. 4. longer sample: We use a longer sample to verify our results at the cost of losing some of the asset classes. 5. Sub-samples: We also performed sub-sample analysis and related to market conditions.

Changing Ranking, Rebalancing and... Table 5 reports the effect of changes in some parameters on different return statistics. We can vary three basic parameters: ranking period, rebalancing period and number of assets. Obviously, the parameters should stay within a reasonable range that would be compatible with momentum. For instance, it does not make sense to use a ranking period beyond one year, because some of the economic reasons that justify momentum in asset prices, e.g. to follow investment flows, would disappear. The return statistics remain very positive even if we depart significantly from the optimal strategy. Among other results, the alpha against the equally-weighted portfolio is statistically and economically significant in all reported cases and it remains significant even outside the reported range.

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com Jan Loeys (44-20) 7325-5473 jan.loeys@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Table 7. Excluding Individual Asset Classes

Average Excess Returns S&P 500 GBI GSCI High Yield EMBI ELMI High Grade MSCI World ex US HFRI Real Estate NAREIT 9.3% 11.1% 9.9% 10.7% 9.2% 11.0% 11.0% 10.3% 10.3% 9.4% Information Ratio (EW) 0.81 1.11 1.01 0.96 0.89 0.98 1.04 0.92 0.98 0.80

Chart 10. Information ratios when 2 asset classes are excluded Frequency in each bin

25 20 15 10 5 0 [0,1)

Source: JPMorgan

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

Chart 9. Sharpe ratios when asset classes are excluded

1.40 1.20 1.00 0.80 MSCI World ex US 0.60 High Grade 0.40 EMBI GSCI ELMI GBI 0.20 0.00

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

[1,1.1) [1.1,1.2) [1.2,1.3) [1.3,1.4) [1.5,1.6) [1.6,1.7) [1.7,1.8]

Chart 11. Information ratios when 3 asset classes are excluded Frequency in each bin

300

Real Estate - NAREIT

250

No Exclusions

High Yield

200 150 100 50 0 [0,0.5)

Source: JPMorgan

S&P 500

The Sharpe ratio is above one in almost all cases, with the exception of the rules that invest in a smaller set of recent winners. In these instances, average returns can be even higher but at the cost of higher risk. Here, we see that other rules that are skewed towards top winners could produce higher average returns. We take a conservative stance with the choice of equal-weighting to avoid data mining. We are searching for rules that can be applied again in the future. We also divide the sample into two halves in order to show that performance is robust to changes in the sample period. Table 6 shows some of the relevant statistics. The alpha remains economically and statistically significant. Excluding asset classes A strategy is strong when it is not highly dependent on the data that we use. Our analysis shows that none of the asset classes are essential for the performance of this strategy.

HFRI

[0.5,0.7) [0.7,0.9) [0.9,1.1) [1.1,1.3) [1.3,1.5) [1.5,1.7)

We compute the returns of the strategy when only 9 out of 10 asset classes are included and consider all 10 possible combinations. Table 7 shows the average excess return over cash and information ratios for all possible exclusions. Additionally, Chart 9 shows the Sharpe ratio for the same exclusions plus the case without any exclusion, the regular cross-market momentum strategy. The performance remains roughly the same. The general message is that momentum strategies are profitable independently of the underlying asset classes that are used.

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Table 8. Adding Asset Classes Statistics Average Excess Return Total Return - Geometric Average Standard Deviation Sharpe Ratio Alpha EW T-stats Beta S&P 500

Source: JPMorgan, Lehman Brothers, MSCI, HFR, NAREIT, Goldman Sachs, S&P

Value 8.91% 13.62% 7.82% 1.14 3.28% 2.56 0.32

Chart 12. Information ratios with partial rebalancing Information ratio for a given ranking period 1.2

1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 -0.2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Source: JPMorgan

Of course, the set of asset classes should be large enough to guarantee that there is sufficient dispersion in returns. If there is no dispersion, there is no reason for momentum. We take this analysis one step further and show that the strategy still outperforms benchmarks if we drop additional asset classes. We drop two or three asset classes and consider the hundreds of possible combinations of seven or eight asset classes. The same momentum rule is applied to each possible combination. Charts 11 and 12 show the histograms of the information ratios over the respective equally-weighted portfolios. First, we see that all combinations generate positive information ratios, which is surprising. Second, many of the combinations produce information ratios that are larger than our standard case. Adding asset classes Any choice of asset classes to be included in the analysis will be arbitrary. But we acknowledge the fact that there is no clear way of decomposing the overall market. We can divide it in terms of style, geographical location and other criteria. During client discussions of this idea, a lot of alternative decompositions were suggested. Results remained robust even with these proposed variations. Here we discuss one of these examples. In this case, the government bond and equity markets are further divided up. The motivation is to increase the potential exposure to government bonds and equities, which is not particularly high in our initial choice of asset classes. The modifications are the following. We replace the government bond component with three individual domestic

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

Chart 13. Sharpe ratios with partial rebalancing Information ratio for a given ranking period

1.35 1.25 1.15 1.05 0.95 0.85 0.75 1 2 3

Source: JPMorgan

4 5 6 7 8

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

markets: US, Europe (proxied by Germany) and Japan. In all cases, we use GBI USD-hedged indices. The initial choices of equity markets are changed and we use instead S&P Value/Barra, S&P Growth/Barra, MSCI World and MSCI Emerging Markets. The alternative composition generates still very positive results. Table 8 presents basic statistics with this new composition. One effect of this new selection is that we increase the average correlation and reduce return dispersion, which could be detrimental to this strategy. Nevertheless, we add more components of equities and bonds that are also subject to momentum. Previous research has shown that both geographical and style decompositions of equities and bonds present momentum. Therefore, it is not surprising that good results are obtained once again.

10

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com Jan Loeys (44-20) 7325-5473 jan.loeys@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Table 9. Momentum strategy with longer sample Statistics Average Excess Return Total Return - Geometric Average Standard Deviation Sharpe Ratio Alpha EW T-stats Alpha S&P 500 T-stats Beta S&P 500

Source: JPMorgan

Value 8.78% 13.76% 10.71% 0.82 3.79% 2.20 6.10% 2.86 1.00

period is between 3 and 12 months, we observe persistence in performance. However, if we use more than that, we start observing reversals in performance. The inverted U-shape that we find is consistent with the behavioural finance theories that advocate that investors overreact to information. This overshooting generates both momentum in the short-run and reversals in the long-run. This result is interesting because it shows that value strategies can also be used in tandem with momentum rules. In fact, if we extend the horizontal axis to include longer ranking periods, you would see negative information ratios8. Longer sample We also tested the cross-market momentum strategy, with a longer sample, starting in 1986. Even though we are forced to use fewer assets because of lack of data, performance remains very strong with an alpha close to 4% a year. In this case, we need to drop hedge funds, currencies and commodities. Table 9 shows the main statistics for this new strategy, but we should highlight a few changes. First, the volatility of the strategy increases because there is a smaller number of asset classes. Second, the beta with respect to the S&P500 also increases becoming 1, but the alpha against the same S&P500 is larger than 6% a year. Sub-samples and relation to market conditions We also analyze the performance of the strategy in subsamples. The strategy outperforms its appropriate benchmark almost always and has a favourable correlation with market conditions. More specifically, we look at the relation between performance over the benchmark and the average return of the equally-weighted portfolio, its volatility and the dispersion in returns of the underlying asset classes.

Partial rebalancing The rebalancing scheme can be changed in order to make it less sensitive to starting dates. One possibility is to rebalance every month. Another is to commit to partial rebalancing every month, which can be less costly and generate less drastic changes in the portfolio. Instead of potentially switching from 0% to 20% and back to 0% every month, we can slowly adjust weights7. This is similar to allocating a fraction of the portfolio to different rules or managers that would rebalance in different months. In this case, the only relevant decision to make is the number of months that we use for ranking period (see Jagadeesh and Titman for a similar approach). Charts 12 and 13 show the Sharpe ratio and information ratio plotted against the number of months used for ranking. Here we see that the momentum remains strong even with a different rebalancing scheme. In both plots, we observe an inverted U-shape. So, it is not effective to use just the last month to rank asset classes, because the short-term trend is not identified. On the other hand, it is also not effective to use more than one year. This result confirms the idea that we should be faster than the average investor. Interestingly, these plots are very similar to the pattern found in momentum with individual equities. Previous research on equity momentum has shown that if the ranking

7 The weights will stay within the 0% to 20% range, but they will move smoothly in the range. For example, we can use a rule that rebalances 1/4, 1/6 or 1/12 of the portfolio every month. Therefore, in the case of a 1/4 rule, the weight on one specific asset class will be 0% if the asset class was never a winner in the last four times we ranked all asset classes. The weight will be 20% if it was a winner in the last four times we computed the rankings, but it can be 15% if it was a winner in three out of the last four times we ranked asset classes.

Future research will address the profitability of simultaneous value and momentum strategies with an alternative framework.

11

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

In order to carry out this exercise, the information ratio of this strategy is calculated for every one-year horizon, allowing for overlapping. We ask whether an investor that implemented this strategy for a one-year horizon would outperform the benchmark. The striking result is that almost all information ratios are positive as we see in Charts 14, 15 and 16. Hence, an investor following this strategy would outperform the benchmark in almost all one-year horizons. In the few cases the strategy underperforms, the magnitude of the information ratio is very small, meaning the underperformance is not significant. These plots illustrate other appealing features of the strategy. The performance is better in market conditions when investors require a higher alpha. First, the information ratio is higher when the market is performing poorly (proxied by the return of the equally-weighted portfolio). Second, the information ratio is higher when the return dispersion is higher. Additionally, the information ratio is higher when the market is more volatile. The driving forces behind momentum require dispersion in returns. If all asset classes had the same realized return over a certain period, there would be no reason to observe momentum in relative performance, because relative performance would be flat.

Chart 14. One-year information ratios and dispersion Information ratio 4.0

3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 0 -1.0 -1.5

Source: JPMorgan

Dispersion

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

Chart 15. One-year information ratios and volatility Information ratio

4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 0 -1.0 -1.5

Source: JPMorgan

Volatility

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

Long-Short and Short Only Strategies

We have focused on the long-only strategy only because it is easier to implement. However, it makes sense to analyse the implications for alpha of long-short and short only strategies, where short positions are taken in the losing asset classes. Chart 17 shows the Sharpe ratio of these different strategies. The short-only strategy has a negative Sharpe ratio, but the alpha is also positive. The negative Sharpe ratio is just a consequence of the negative exposure to the overall market. The long-short strategy has a smaller Sharpe ratio than the long-only version, but the reason is the lack of exposure to the overall market.

Chart 16. One-year information ratios and average return Information ratio 4.0

3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 -0.2 -1.0 -1.5

Source: JPMorgan

EW portfolio return

-0.1

0.1

0.2

0.3

12

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com Jan Loeys (44-20) 7325-5473 jan.loeys@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Tables 10 and 11 show that the alphas for all strategies are roughly the same, implying we can exploit momentum in many different ways. The profitability of the long-only strategy is due to the implicit long-short strategy. They have similar alphas and information ratios.

Table 10. Long-short strategy - main statistics Statistics Average Excess Return Standard Deviation Sharpe Ratio Alpha EW T-stats Beta S&P 500 Value 3.81% 3.92% 0.97 4.12% 3.5 -0.05

Momentum strategies in individual markets

A natural concern about any strategy that uses only past return information is whether it will remain profitable. A possible reason for the disappearance of the profitability is the simple fact that investors become aware of it, exploit it and eliminate the inefficiency10. Interestingly, the inflow of additional momentum investors may actually reinforce momentum in financial prices. We revisit the analysis of momentum in the equity markets to show that it is still strong, even though investors have been aware of its existence for quite a long time. This is an out-ofsample analysis, as the beginning of our sample is posterior to the publication of the article by Jagadeesh and Titman (1993) that proposed the equity momentum strategy. We consider three different equity momentum strategies that rely on previous research: 1. Price momentum: based on a rule that forms portfolios of individual stocks based on both size and prior return (past one-year return excluding the most recent month). This series and detailed description are available at Professor Kenneth Frenchs website10. 2. Industry momentum: a simple rule that is long winning industries and short losing industries. The industry classification is based on data available at Professor Kenneth Frenchs website. We use 30 industry portfolios. 3. Style momentum: this rule first divides the overall equity market into 25 portfolios based on book-to-market ratio and market capitalization of equity. Then, we go long winning styles and short losing styles. All of the momentum strategies have positive Sharpe ratios. Chart 18 shows the Sharpe ratio of two versions of the cross-market momentum strategy and three alternative equity momentum strategies using the same sample period (January 1994 to April 2005 due to data limitations). We see that all the equity momentum strategies remain profitable.

Table 11. Short only strategy - main statistics Statistics Average Excess Return Standard Deviation Sharpe Ratio Alpha EW T-stats Beta S&P 500

Source: JPMorgan

Value -2.32% 8.25% -0.28 4.13% 3.61 -0.40

Chart 17. Sharpe ratio for cross-market strategies

Long Only

Long Short

Short Only

-0.5

Source: JPMorgan

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

Interestingly, we are ignoring a lot of the refinements that have been proposed in subsequent research. Moreover, we are not optimizing these rules for the current sample, and just using simple and previously used rules.

Another reason is that performance may result from data snooping or plain luck. In the case of luck, only time will tell us whether the cross-market momentum strategy is indeed reliable.

13

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Chart 18. Sharpe ratio for cross-market and equity strategies 1.60

1.40 1.20 1.00 0.80 0.60 0.40 0.20 0.00

Cro ssM arket

Source: JPMorgan

Chart 19. Return decomposition for long only strategy

14.5%

Long Winners 5 Winners

10.4%

Equally-Weighted 5 Winners

4.1%

Long Winners Short Losers

=

5 Losers

5 Winners

5 Losers

Passive

Source: JPMorgan

Active

Cro ssM arket Lo ng-Short

Equity Industry

Equity Style Equity P rice

Table 12. Correlation for all strategies X-Mkt X-Mkt X-Mkt LS Industry Style Price

Source: JPMorgan

X-Mkt LS 1.00 0.38 0.27 0.49

Industry

Style

Price

1.00 0.40 0.30 0.13 0.09

A long-only strategy is exposed to the overall market, but the active selection adds alpha to the benchmark portfolio, which is a portfolio that invests in all asset classes at the same time. Chart 19 shows the a graphical decomposition of the long-only strategy into passive and active components. The active component is the implicit long-short position of the portfolio. In the past sample, the performance of the passive component was quite favourable, but we would not expect similar performance in next few years, because of the current valuations. Here we are most interested in the contribution of the active component. The analysis here is based on a very short sample, but it provides a guideline for future analysis. Momentum may disappear or change as investors become aware of its existence. Even if it changes, the direction of a possible transformation is not clear. It can become shorter or longer. Moreover, an asset allocation decision cannot be based solely on momentum arguments. Value considerations are also vital to an optimal asset allocation. But momentum can always be used as an overlay to an existing portfolio, creating a separate source of alpha. The analysis here is focused on only one dimension of the asset allocation process, but momentum should be used as an additional tool. The objective was to show that an active rule based solely on momentum could outperform a passive

1.00 0.43 0.62

1.00 0.63

1.00

This analysis shows that equity momentum is not necessarily a sample-specific observation. The price momentum strategy had an average annualized monthly return of 15.02% in 2005 including data up to November. Table 12 shows that the cross-market momentum strategy is not highly correlated with the other momentum strategies. They can be combined in order to benefit from diversification.

Conclusions and Caveats

This analysis shows that it makes sense to use a momentum strategy in asset allocation that includes a diversified set of strategies/asset classes. Nonetheless, a few caveats are also necessary.

1 0 See Prof. Kenneth Frenchs website at http:// mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html

14

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com Jan Loeys (44-20) 7325-5473 jan.loeys@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

benchmark. The benchmark was not necessarily the optimal benchmark, since we ignored the difference in risk and expected returns across asset classes. But all these considerations can be easily added. Another possible drawback is the loss in performance due to higher replication costs. The implementation costs reduce the alpha, but it remains significantly positive. JPMorgan has created structured products that use the strategy proposed here as underlying risky asset with similar costs as considered here. The underlying is called the Investible Global Asset Rotator (IGAR). The IGAR index replicates the strategy using the same indices in most of the cases, or funds that follow similar strategies. JPMorgan also considered variations of this strategy with positive results. These products show that the idea adds alpha independently of implementation costs. Chart 20 shows the suggested allocations for the current semester and previous two years. The current allocation is invested in S&P 500, MSCI World ex US, hedge funds, commodities and real estate.

Chart 20. Recent strategy allocation

2004 H1 S&P 500 MSCI World ex US GBI High Grade High Yield EMBI ELMI Real Estate GSCI HFRI

Source: JPMorgan

2004 H2

2005 H1

2005 H2

2006 H1

15

J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Ruy Ribeiro (44-20) 7777-1390 ruy.m.ribeiro@jpmorgan.com

Market Strategy Exploiting Cross-Market Momentum February 8, 2006

Investment Strategies Series

The Investment Strategies series aims to offer new approaches and methods on investing and trading profitably in financial markets. 1. Rock-Bottom Spreads, Peter Rappoport, Oct 2001 2. Understanding and Trading Swap Spreads, Laurent Fransolet, Marius Langeland, Pavan Wadhwa, Gagan Singh, Dec 2001 3. New LCPI trading rules: Introducing FX CACI, Larry Kantor, Mustafa Caglayan, Dec 2001 4. FX Positioning with JPMorgans Exchange Rate Model, Drausio Giacomelli, Canlin Li, Jan 2002 5. Profiting from Market Signals, John Normand, Mar 2002 6. A Framework for Long-term Currency Valuation, Larry Kantor and Drausio Giacomelli, Apr 2002 7. Using Equities to Trade FX: Introducing LCVI, Larry Kantor and Mustafa Caglayan, Oct 2002

8. Alternative LCVI Trading Strategies, Mustafa Caglayan, Jan 2003 9. Which Trade, John Normand, Jan 2004 10. JPMorgans FX & Commodity Barometer, John Normand, Mustafa Caglayan, Daniel Ko, Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou and Lei Shen, Sep 2004. 11. A Fair Value Model for US Bonds, Credit and Equities, Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou and Jan Loeys, Jan 2005. 12. JPMorgan Emerging Market Carry-to-RiskModel, Osman Wahid, February 2005 13. Valuing cross-market yield spreads, Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, January 2006 14. Exploiting cross-market momentum, Ruy Ribeiro and Jan Loeys, February 2006

The analyst(s) denoted by an * hereby certifies that: (1) all of the views expressed in this research accurately reflect his or her personal views about any and all of the subject securities or issuers; and (2) no part of any of the analysts compensation was, is, or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed by the analyst(s) in this research.

Analysts Compensation: The research analysts responsible for the preparation of this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including the quality and accuracy of research, client feedback, competitive factors and overall firm revenues. The firms overall revenues include revenues from its investment banking and fixed income business units. Ratings System: JPMorgan uses the following sector/issuer portfolio weightings: Overweight (over the next three months, the recommended risk position is expected to outperform the relevant index, sector, or benchmark), Neutral (over the next three months, the recommended risk position is expected to perform in line with the relevant index, sector, or benchmark), and Underweight (over the next three months, the recommended risk position is expected to underperform the relevant index, sector, or benchmark). JPMorgan uses the following fundamental credit recommendations: Improving (the issuers credit profile/credit rating likely improves over the next six to twelve months), Stable (the issuers long-term credit profile/credit rating likely remains the same over the next six to twelve months), Deteriorating (the issuers long-term credit profile/credit rating likely falls over the next six to twelve months), Defaulting (there is some likelihood that the issuer defaults over the next six to twelve months). Valuation & Methodology: In JPMorgans credit research, we assign a rating to each issuer (Overweight, Underweight or Neutral) based on our credit view of the issuer and the relative value of its securities, taking into account the ratings assigned to the issuer by credit rating agencies and the market prices for the issuers securities. Our credit view of an issuer is based upon our opinion as to whether the issuer will be able service its debt obligations when they become due and payable. We assess this by analyzing, among other things, the issuers credit position using standard credit ratios such as cash flow to debt and fixed charge coverage (including and excluding capital investment). We also analyze the issuers ability to generate cash flow by reviewing standard operational measures for comparable companies in the sector, such as revenue and earnings growth rates, margins, and the composition of the issuers balance sheet relative to the operational leverage in its business. Other Disclosures: Planned Frequency of Updates: JPMorgan provides periodic updates on companies/industries based on company-specific developments or announcements, market conditions or any other publicly available information. Legal Entities: JPMorgan is the marketing name for JPMorgan Chase & Co. and its subsidiaries and affiliates worldwide. J.P. Morgan Securities Inc. is a member of NYSE and SIPC. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. is a member of FDIC and is authorized and regulated in the UK by the Financial Services Authority. J.P. Morgan Futures Inc., is a member of the NFA. J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. (JPMSL) is a member of the London Stock Exchange and is authorized and regulated by the Financial Services Authority. J.P. Morgan Equities Limited is a member of the Johannesburg Securities Exchange and is regulated by the FSB. J.P. Morgan Securities (Asia Pacific) Limited (CE number AAJ321) is regulated by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority. JPMorgan Chase Bank, Singapore branch is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. J.P. Morgan Securities Asia Private Limited is regulated by the MAS and the Financial Services Agency in Japan. J.P. Morgan Australia Limited (ABN 52 002 888 011/AFS Licence No: 238188) (JPMAL) is regulated by ASIC. General: Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but JPMorgan does not warrant its completeness or accuracy except with respect to any disclosures relative to JPMSI and/or its affiliates and the analysts involvement with the issuer. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as at the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The investments and strategies discussed here may not be suitable for all investors; if you have any doubts you should consult your investment advisor. The investments discussed may fluctuate in price or value. Changes in rates of exchange may have an adverse effect on the value of investments. This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. JPMorgan and/or its affiliates and employees may act as placement agent, advisor or lender with respect to securities or issuers referenced in this report.. Clients should contact analysts at and execute transactions through a JPMorgan entity in their home jurisdiction unless governing law permits otherwise. This report should not be distributed to others or replicated in any form without prior consent of JPMorgan. U.K. and European Economic Area (EEA): Investment research issued by JPMSL has been prepared in accordance with JPMSLs Policies for Managing Conflicts of Interest in Connection with Investment Research, which can be found at http://www.jpmorgan.com/pdfdoc/research/ConflictManagementPolicy.pdf. This report has been issued in the U.K. only to persons of a kind described in Article 19 (5), 38, 47 and 49 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2001 (all such persons being referred to as relevant persons). This document must not be acted on or relied on by persons who are not relevant persons. Any investment or investment activity to which this document relates is only available to relevant persons and will be engaged in only with relevant persons. In other EEA countries, the report has been issued to persons regarded as professional investors (or equivalent) in their home jurisdiction. Germany: This material is distributed in Germany by J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. Frankfurt Branch and JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., Frankfurt Branch who are regulated by the Bundesanstalt fr Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht. Australia: This material is issued and distributed by JPMAL in Australia to wholesale clients only. JPMAL does not issue or distribute this material to retail clients. The recipient of this material must not distribute it to any third party or outside Australia without the prior written consent of JPMAL. For the purposes of this paragraph the terms wholesale client and retail client have the meanings given to them in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001. JPMAL may hold an interest in the financial product referred to in this report. JPMCB, N.A. may make a market or hold an interest in the financial product referred to in this report. Korea: This report may have been edited or contributed to from time to time by affiliates of J.P. Morgan Securities (Far East) Ltd, Seoul branch. Revised 4 January 2006. Copyright 2006 JPMorgan Chase & Co. All rights reserved. Additional information available upon request.

16

You might also like

- Markowitz in Tactical Asset AllocationDocument12 pagesMarkowitz in Tactical Asset AllocationsoumensahilNo ratings yet

- Ribeiro Volatility 2012Document16 pagesRibeiro Volatility 2012pbecker126100% (2)

- Qis - Insights - Qis Insights Style InvestingDocument21 pagesQis - Insights - Qis Insights Style Investingpderby1No ratings yet

- AQR - Chasing Your Own Tail RiskDocument9 pagesAQR - Chasing Your Own Tail RiskTimothy IsgroNo ratings yet

- Signal Processing 20101110Document36 pagesSignal Processing 20101110smysona100% (2)

- Relative Value Single Stock VolatilityDocument12 pagesRelative Value Single Stock VolatilityTze Shao100% (2)

- DBG 020911 94525Document48 pagesDBG 020911 94525experquisite100% (1)

- Dispersion - A Guide For The CluelessDocument6 pagesDispersion - A Guide For The CluelessCreditTraderNo ratings yet

- JPM 2015 Equity Derivati 2014-12-15 1578141 PDFDocument76 pagesJPM 2015 Equity Derivati 2014-12-15 1578141 PDFfu jiNo ratings yet

- Volatility Signals For Asset AllocationDocument12 pagesVolatility Signals For Asset AllocationsoumensahilNo ratings yet

- Dispersion Trading: Many ApplicationsDocument6 pagesDispersion Trading: Many Applicationsjulienmessias2100% (2)

- (BNP Paribas) Smile TradingDocument9 pages(BNP Paribas) Smile TradingBernard Rogier100% (2)

- Dispersion Trade Option CorrelationDocument27 pagesDispersion Trade Option Correlationmaf2014100% (2)

- Dion Market Timing ModelDocument18 pagesDion Market Timing Modelxy053333100% (1)

- Derivatives Strategy: Factors Behind Single Stock VolatilityDocument10 pagesDerivatives Strategy: Factors Behind Single Stock Volatilityhc87No ratings yet

- GS-Implied Trinomial TreesDocument29 pagesGS-Implied Trinomial TreesPranay PankajNo ratings yet

- Nomura US Vol AnalyticsDocument26 pagesNomura US Vol Analyticshlviethung100% (2)

- CDocument16 pagesC7610216922No ratings yet

- (JP Morgan) Introducing The JPMorgan Cross Sectional Volatility Model & ReportDocument13 pages(JP Morgan) Introducing The JPMorgan Cross Sectional Volatility Model & ReportScireaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Duration and Volatility: Salomon Brothers IncDocument32 pagesUnderstanding Duration and Volatility: Salomon Brothers IncoristhedogNo ratings yet

- JPMorgan Cross Asset CorrelationsDocument28 pagesJPMorgan Cross Asset Correlationstanmartin100% (2)

- ACOMB-Correlation in PracticeDocument25 pagesACOMB-Correlation in PracticefloqfloNo ratings yet

- QIS: Equity: Investment ObjectiveDocument4 pagesQIS: Equity: Investment ObjectivepwnwchNo ratings yet

- Which Free Lunch Would You Like Today, Sir?: Delta Hedging, Volatility Arbitrage and Optimal PortfoliosDocument104 pagesWhich Free Lunch Would You Like Today, Sir?: Delta Hedging, Volatility Arbitrage and Optimal PortfolioskabindingNo ratings yet

- 2018 Equity Volatility Outlook Credit SuisseDocument47 pages2018 Equity Volatility Outlook Credit SuissePipi Ququ0% (1)

- Uncertainty and Style Dynamics: Portfolios Under ConstructionDocument27 pagesUncertainty and Style Dynamics: Portfolios Under ConstructionRaphael100% (1)

- From Thesis To Trading A Trend PDFDocument25 pagesFrom Thesis To Trading A Trend PDFfnmeaNo ratings yet

- Dispersion Trading HalleODocument29 pagesDispersion Trading HalleOHilal Halle OzkanNo ratings yet

- Trading the Volatility SkewDocument11 pagesTrading the Volatility Skewhc87No ratings yet

- Index Variance Arbitrage: Arbitraging Component CorrelationDocument39 pagesIndex Variance Arbitrage: Arbitraging Component Correlationcclaudel09No ratings yet

- Quanto Lecture NoteDocument77 pagesQuanto Lecture NoteTze Shao100% (1)

- Risk Premia Strategies B 102727740Document29 pagesRisk Premia Strategies B 102727740h_jacobson100% (4)

- Multifractal Volatility: Theory, Forecasting, and PricingFrom EverandMultifractal Volatility: Theory, Forecasting, and PricingNo ratings yet

- Auto Call 1Document24 pagesAuto Call 1Jérémy HERMANTNo ratings yet

- Nomura QuantDocument120 pagesNomura QuantArtur Silva100% (1)

- Quantitative Asset Manage 102727754Document31 pagesQuantitative Asset Manage 102727754h_jacobson67% (3)

- (JP Morgan) Relative Value Single Stock VolatilityDocument36 pages(JP Morgan) Relative Value Single Stock VolatilityDylan Adrian100% (1)

- JPM Bond CDS Basis Handb 2009-02-05 263815Document92 pagesJPM Bond CDS Basis Handb 2009-02-05 263815ccohen6410100% (1)

- Asset Swaps to Z-spreads: An Introduction to Swaps, Present Values, and Z-SpreadsDocument20 pagesAsset Swaps to Z-spreads: An Introduction to Swaps, Present Values, and Z-SpreadsAudrey Lim100% (1)

- Can Alpha Be Captured by Risk Premia PublicDocument25 pagesCan Alpha Be Captured by Risk Premia PublicDerek FultonNo ratings yet

- Macquarie TechnicalsDocument30 pagesMacquarie TechnicalsKevin MacCullough100% (2)

- (Deutsche Bank) Modeling Variance Swap Curves - Theory and ApplicationDocument68 pages(Deutsche Bank) Modeling Variance Swap Curves - Theory and ApplicationMaitre VinceNo ratings yet

- IR - Quant - 101105 - Is It Possible To Reconcile Caplet and Swaption MarketsDocument31 pagesIR - Quant - 101105 - Is It Possible To Reconcile Caplet and Swaption MarketsC W YongNo ratings yet

- Dispersion TradesDocument41 pagesDispersion TradesLameune100% (1)

- Barclays Capital Equity Correlation Explaining The Investment Opportunity PDFDocument2 pagesBarclays Capital Equity Correlation Explaining The Investment Opportunity PDFAnonymous s41KVlqkNo ratings yet

- SkewDocument34 pagesSkewnblanc88100% (4)

- Introduction To Conditional Variance SwapsDocument2 pagesIntroduction To Conditional Variance SwapstsoutsounisNo ratings yet

- Convexity and VolatilityDocument20 pagesConvexity and Volatilitydegas981100% (2)

- FX Deal ContingentDocument23 pagesFX Deal ContingentJustinNo ratings yet

- GS - Quantamentals - The Quality FactorDocument10 pagesGS - Quantamentals - The Quality Factormac roNo ratings yet

- Market and Volatility CommentaryDocument8 pagesMarket and Volatility Commentarymaoychris100% (1)

- Barclays Special Report Market Neutral Variance Swap VIX Futures StrategiesDocument23 pagesBarclays Special Report Market Neutral Variance Swap VIX Futures Strategiesicefarmcapital100% (1)

- The High Frequency Game Changer: How Automated Trading Strategies Have Revolutionized the MarketsFrom EverandThe High Frequency Game Changer: How Automated Trading Strategies Have Revolutionized the MarketsNo ratings yet

- Trading the Fixed Income, Inflation and Credit Markets: A Relative Value GuideFrom EverandTrading the Fixed Income, Inflation and Credit Markets: A Relative Value GuideNo ratings yet

- Answers To Concepts Review and Critical Thinking QuestionsDocument6 pagesAnswers To Concepts Review and Critical Thinking QuestionsHimanshu KatheriaNo ratings yet

- AC3202 WK2 Exercises SolutionsDocument11 pagesAC3202 WK2 Exercises SolutionsLong LongNo ratings yet

- January Monthly Current Affairs Compiled PDFDocument70 pagesJanuary Monthly Current Affairs Compiled PDFPiyali SenNo ratings yet

- Banyan Tree Holdings RestructuringDocument18 pagesBanyan Tree Holdings RestructuringdfghfiNo ratings yet

- IA 3 - BVPS and EPS - SolutionsDocument22 pagesIA 3 - BVPS and EPS - SolutionsPatríck LouieNo ratings yet

- Midland Energy F13Document33 pagesMidland Energy F13Juan Ramon Aguirre RondinelNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow FormulaDocument2 pagesCash Flow FormulaSubhas ChettriNo ratings yet

- Antam Profits Rp293 Billion in 9 MonthsDocument10 pagesAntam Profits Rp293 Billion in 9 MonthsArdiansyah HandikaNo ratings yet

- The Economic Times Wealth - March 27 2023Document26 pagesThe Economic Times Wealth - March 27 2023Bakary DjabyNo ratings yet

- A Call For A Temporary Moratorium On "The DAO"Document13 pagesA Call For A Temporary Moratorium On "The DAO"SoftpediaNo ratings yet

- HSBC Project Report DRAFT1Document94 pagesHSBC Project Report DRAFT1hikvNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22 - Retained EarningsDocument8 pagesChapter 22 - Retained EarningsOJERA, Allyna Rose V. BSA-1BNo ratings yet

- Financial Derivatives in Diff ProspectDocument7 pagesFinancial Derivatives in Diff ProspectNishantNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Financial Management Chapter 1Document30 pagesIntroduction to Financial Management Chapter 1Mark DavidNo ratings yet

- All Schemes Half Yearly Portfolio - As On 31 March 2020Document1,458 pagesAll Schemes Half Yearly Portfolio - As On 31 March 2020anjuNo ratings yet

- Tay Yu Jie - ResumeDocument1 pageTay Yu Jie - ResumeTay Yu JieNo ratings yet

- Ratios Analysis For StudentsDocument16 pagesRatios Analysis For StudentsMichael AsieduNo ratings yet

- Relaxations & Amendments in Companies Act WebinarDocument37 pagesRelaxations & Amendments in Companies Act WebinarAbhishek PareekNo ratings yet

- 1st Midterm Quiz QuestionnaireDocument11 pages1st Midterm Quiz QuestionnaireAthena Fatmah AmpuanNo ratings yet

- Philippine Interpretations Committee (Pic) Questions and Answers (Q&As)Document6 pagesPhilippine Interpretations Committee (Pic) Questions and Answers (Q&As)verycooling100% (1)

- Finals - Assignment 4 PDFDocument2 pagesFinals - Assignment 4 PDFcharlies parrenoNo ratings yet

- Inflation Impact on Monthly Expenditure over 30 YearsDocument8 pagesInflation Impact on Monthly Expenditure over 30 Yearslove4u1lyNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument1 pageReportumaganNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Point & Figure and Candle Charting MamualDocument22 pagesIntroduction To Point & Figure and Candle Charting Mamualesthermays50% (4)

- Mutual Funds: Learning OutcomesDocument39 pagesMutual Funds: Learning OutcomesBAZINGANo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment 1 PDFDocument5 pagesIndividual Assignment 1 PDFNanthini KrishnanNo ratings yet

- 201FIN Tutorial 3 Financial Statements Analysis and RatiosDocument3 pages201FIN Tutorial 3 Financial Statements Analysis and RatiosAbdulaziz HNo ratings yet

- Wiley CPAexcel - BEC - Assessment Review - 2Document20 pagesWiley CPAexcel - BEC - Assessment Review - 2ABCNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Bfsi Industry in India: Prepared by Devansh VermaDocument4 pagesAnalysis of Bfsi Industry in India: Prepared by Devansh VermaDevansh VermaNo ratings yet