Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Architecture and Social Change Summary and Critique

Uploaded by

sfwhitehornOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Architecture and Social Change Summary and Critique

Uploaded by

sfwhitehornCopyright:

Available Formats

Architecture and Social Change:

The Struggle for Affordable Housing in Oakland's Uptown Project

Alex Salazar

Summary: Salazar's Architecture and Social Change is a comprehensive case study into community activism and organization. Using Oakland's controversial Uptown Project as a backdrop for socio-economic discrepancy, conflict, and resolution, Architecture and Social Change meets a ubiquitous urban problem of displacement with solutions of community organization. Within this case, we are presented with disconnections within the professions of architecture and planning, urban implications as a result of resistance and retaliation, and courses of action that have been proven to be successful in organizing against displacement. Salazar argues that the disconnections that happen between both architecture and planning practices and the community are initiated within the professions themselves. Salazar argues that mainstream architectural practices often categorize community design as simply a method of acquiring projects through the city planning department. While practices are swelling in size and sophistication further perpetuating competition for larger projects, so does the distance between practice and community. Inadvertently, grassroots and nonprofit developers suffer as their efforts are shadowed by award-winning firms and their visions of grandeur for a community in which they do not know or identify with. Salazar sets forth a call to action for young architects to not only use professional efforts for the progress of their firm, but to donate skills learned to causes of conscious design and development within communities facing renewal and displacement. Salazar address the history of resistance and retaliation as both a benefit and burden to the city of Oakland.The history of Oakland had been marked with forms of resistance such as the forming of the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army which both took militant approaches at demanding equality for minorities, equal housing, anti-redlining, while simultaneously providing negative representations of the inner city. This resistance coupled with a decline in wartime production, inflated rent, and the middle to upperclass flight to extremities of the city disproportionately affected development of the inner city. In 1998, Mayor Jerry Brown proposed a 60 million dollar urban renewal project that would bring 10,000 residents into downtown Oakland while displacing thousands of longtime residents who were majority low income households. The most controversial of the proposal is the Uptown Project, a 1040 unit project that would renew and displace hundreds of residents living in single room hotels. At this moment we begin to understand the power of organization against the power of metropolitics. Salazar examines the efforts of the Coalition for Workforce Housing, an umbrella of volunteer architects and planners, community activists and advocates, and its integrated approach in the development of the Uptown Project. Making demands, bringing media pressure to city officials, and acting as public policy watchdogs were the actions of the coalition. From initiating a gentrification tour of areas affected by the project bringing media attention to the response of city officials to making demands of portions of the project to be

dedicated to low income housing including social services made a significant impact in the project. The CWH even hosted a charette that included volunteer practitioners, city representatives, and developers in which testimonies and presentations on funding sources were given as well. While this is only a summary of actions taken on behalf of the CWH, Architecture and Social Change celebrates this case study as a model for other cities facing disproportionate renewal and displacement. Critique: I feel that Salazar positions his argument as a constant shift in blame for urban decomposition and socio-economic neglect. Could this strategy actually mask the genuine intention of submitting a call for consciousness amongst designers, cities governments, and residents? Instead of presenting the case study as a fragmented study of compartmental ignorance and or neglect, perhaps there is a way of integrating the successes that each posses as a basis for encouragement and enlightenment. What I believe lacks in the publication is the condition in which these low-income communities existed previously. While the text does mention the single room hotels that low-income households dwelled in, it did not mention the emotional, psychological, and social experiences of bodies that lived, dwelled, and transitioned through these spaces. Could there have truly been a need for a complete reconceptualization of space and its function that existed at that site? There exists a slippery slope in the term gentrification and slumification as ex-Oakland mayor defines it. While this text can easily gain emotional traction in that any displacement is bad displacement , we must also examine the risks associated with the allowing those pre-Uptown conditions to exist and possibly serve as a catalyst for future deterioration. What I do appreciate about Salazar's arguments is calling out the specific demands of the CWH in that front stoops and windows and the orientation of dwellings towards the street as strategies of providing safety that community encompasses. While this design decision may be a miniscule point brought about in his argument, it resonated with me in that other readings I have investigated fail to address public housing strategies that promote the true experiential nuances of community. Most important I appreciate this publication because it is a call to action providing a case in which strategies have proven successful. There exists a slippery slope between pontification and action in terms of activism with the field of architecture. Even when activism within architecture is recognized ,it is constrained to institutions such as Architecture for Humanity, DesignCorps, PublicArchitecture, etc. Architecture and Social Change challenges this lens by providing possibilities of individual volunteering and donating our services as practitioners to the benefits of those who do not fully discern the power of shaping the spaces in which we inhabit. It is as if Salazar is questioning our efforts and if they are truly in vain or beneficial to the public good. Salazar identifies the powers that are in warfare: political and organizational. While engaging the text it was important for me to keep a discerning eye on embedded, or blatant, structures of power that exist in the built environment. By investigating this case study am I given the opportunity to witness a positive form of utilizing power. This power is a power that not only lies in the collective body of organization, but also within the individual decision to dedicate one's time, talent, and skills to the betterment of the physical environment around us.

You might also like

- Visualizing The Invisible - Towards An Urban SpaceDocument197 pagesVisualizing The Invisible - Towards An Urban SpaceManisha Balani MahalaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Urban SociologyDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Urban Sociologyafmcpdbnr100% (1)

- Innovating Places: A New Role For Place Difference'Document13 pagesInnovating Places: A New Role For Place Difference'Nesta100% (1)

- Planning and The Just City: January 2006Document31 pagesPlanning and The Just City: January 2006Abl BasperNo ratings yet

- Cities Within The City: Do-It-Yourself Urbanism and The Right To The CityDocument16 pagesCities Within The City: Do-It-Yourself Urbanism and The Right To The CityAditi AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Who Has The Right To The CityDocument11 pagesWho Has The Right To The CityCeNo ratings yet

- Planning for New Towns: Bridging Theory and PracticeDocument20 pagesPlanning for New Towns: Bridging Theory and PracticeMilad RajabiNo ratings yet

- Building The Inclusive CityDocument157 pagesBuilding The Inclusive CityMuhammad Rahmat Agung SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Rosalyn Deutsche, Uneven DevelopmentDocument51 pagesRosalyn Deutsche, Uneven DevelopmentLauren van Haaften-SchickNo ratings yet

- ARCH020 Response Paper 1Document3 pagesARCH020 Response Paper 1yamenalmohtar7No ratings yet

- The City Is the Factory: New Solidarities and Spatial Strategies in an Urban AgeFrom EverandThe City Is the Factory: New Solidarities and Spatial Strategies in an Urban AgeNo ratings yet

- Common Space As Threshold Space - StavridesDocument13 pagesCommon Space As Threshold Space - StavrideskhyatiandrapiyaNo ratings yet

- Public Investment and Gentrification Risk DisplacementDocument14 pagesPublic Investment and Gentrification Risk DisplacementMunna ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Cultural Districts Crossing Line Borrup 2015Document20 pagesCultural Districts Crossing Line Borrup 2015María ColladoNo ratings yet

- Michael Dear & Steven Flusty (1998) Postmodern Urbanism, Annals of The Association of American Geographers, 88.1, 50-72Document24 pagesMichael Dear & Steven Flusty (1998) Postmodern Urbanism, Annals of The Association of American Geographers, 88.1, 50-72MoocCBTNo ratings yet

- Pratt 2011Document8 pagesPratt 2011Oana SerbanNo ratings yet

- CHP 9 Assessment Article-1Document4 pagesCHP 9 Assessment Article-1api-589496955No ratings yet

- Social Innovation - The New Arms RaceDocument17 pagesSocial Innovation - The New Arms Raceapi-260891476No ratings yet

- Rittel - Webber - 1973 - Dilemmas in A General Theory of PlanningDocument16 pagesRittel - Webber - 1973 - Dilemmas in A General Theory of PlanningClyde MatthysNo ratings yet

- Urban SprawlDocument3 pagesUrban SprawlJohnDominicMoralesNo ratings yet

- Advocacy and Community PlanningDocument4 pagesAdvocacy and Community PlanningNurshazwani OsmanNo ratings yet

- Mobile structures revitalize citiesDocument4 pagesMobile structures revitalize cities8zero8No ratings yet

- Rittel+Webber "Dilemmas in A General Theory of Planning"Document15 pagesRittel+Webber "Dilemmas in A General Theory of Planning"Kenya WheelerNo ratings yet

- Book IntroductionDocument3 pagesBook IntroductionsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Coiacetto Eddo - Urban Social Structure - A Focus On The Development IndustryDocument13 pagesCoiacetto Eddo - Urban Social Structure - A Focus On The Development IndustryNeli KoutsandreaNo ratings yet

- Cities for Profit: The Real Estate Turn in Asia’s Urban PoliticsFrom EverandCities for Profit: The Real Estate Turn in Asia’s Urban PoliticsNo ratings yet

- THE Do-It-Yourself: Occupa Tion GuideDocument16 pagesTHE Do-It-Yourself: Occupa Tion GuideRaphael X PosteraroNo ratings yet

- 1973 Rittel and Webber Wicked ProblemsDocument16 pages1973 Rittel and Webber Wicked ProblemsDouglas PastoriNo ratings yet

- Reverse Migration - SorensenDocument7 pagesReverse Migration - SorensenLyka Mae SembreroNo ratings yet

- Whitehorn - Shawn 9.22.11Document1 pageWhitehorn - Shawn 9.22.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- What People Say Re I C Inquiry ActionDocument7 pagesWhat People Say Re I C Inquiry ActionMariaNo ratings yet

- J Reading Assignment 2Document4 pagesJ Reading Assignment 2jerusalem sintayehuNo ratings yet

- UrbanismoDocument89 pagesUrbanismomies126100% (1)

- The CityDocument37 pagesThe CityIvini FerrazNo ratings yet

- Park, Robert, 1915-The City-Escola de ChicagoDocument36 pagesPark, Robert, 1915-The City-Escola de ChicagoLeticia MiguelNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument37 pagesThe University of Chicago PressVlad SchülerNo ratings yet

- Rittel Webber 1973Document16 pagesRittel Webber 1973victorNo ratings yet

- 0201Document25 pages0201mymalvernNo ratings yet

- Escape Into The City, EverydayDocument19 pagesEscape Into The City, EverydayohoudNo ratings yet

- Life Among Urban Planners: Practice, Professionalism, and Expertise in the Making of the CityFrom EverandLife Among Urban Planners: Practice, Professionalism, and Expertise in the Making of the CityNo ratings yet

- Amira Osman - Thoughts On The Role of Architects in Two African Contexts - The Re-Making of Urban IdentityDocument29 pagesAmira Osman - Thoughts On The Role of Architects in Two African Contexts - The Re-Making of Urban IdentityIsabel Van WykNo ratings yet

- Senior High School: First Semester S.Y. 2020-2021Document10 pagesSenior High School: First Semester S.Y. 2020-2021NylinamNo ratings yet

- Gentrification and Its Effects On Minority Communities - A Comparative Case Study of Four Global Cities: San Diego, San Francisco, Cape Town, and ViennaDocument24 pagesGentrification and Its Effects On Minority Communities - A Comparative Case Study of Four Global Cities: San Diego, San Francisco, Cape Town, and ViennaPremier PublishersNo ratings yet

- Smith N - Gentrification and Uneven DevelopmentDocument18 pagesSmith N - Gentrification and Uneven DevelopmentnllanoNo ratings yet

- Urban Hacking: The Versatile Forms of Cultural Resilience in Hong KongDocument14 pagesUrban Hacking: The Versatile Forms of Cultural Resilience in Hong KongYoshitomo MoriokaNo ratings yet

- Ecology of VulnerabilityDocument54 pagesEcology of VulnerabilityjadedoctopusNo ratings yet

- A Critical Method: Public Space San FranciscoDocument12 pagesA Critical Method: Public Space San FranciscoSean StillwellNo ratings yet

- Davidoff 1965 Advocacy and Pluralism in PlanningDocument12 pagesDavidoff 1965 Advocacy and Pluralism in PlanningIsraa HafiqahNo ratings yet

- 2013 PDFFDocument8 pages2013 PDFFCorina ElenaNo ratings yet

- Redevelopment-Importance of Preserving The Community: Case of Dharavi ProjectDocument34 pagesRedevelopment-Importance of Preserving The Community: Case of Dharavi ProjectVikas KhannaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Planning History 2003 Wagner 331 55Document26 pagesJournal of Planning History 2003 Wagner 331 55arnav saikiaNo ratings yet

- Small Info For LSEDocument21 pagesSmall Info For LSEFast MarketersNo ratings yet

- DIY Urbanism HistoryDocument14 pagesDIY Urbanism HistoryKahaNo ratings yet

- Open-Source Urbanism: Creating, Multiplying and Managing Urban CommonsDocument18 pagesOpen-Source Urbanism: Creating, Multiplying and Managing Urban CommonsYuxinWuNo ratings yet

- The Privatization of Public Space NeolibDocument10 pagesThe Privatization of Public Space NeolibJuanpablo Barbieri VenegasNo ratings yet

- The Urban Question WalterDocument20 pagesThe Urban Question WaltermahmoudNo ratings yet

- The Social Design Public Action ReaderDocument83 pagesThe Social Design Public Action ReaderRita Vila-ChãNo ratings yet

- Doina Petrescu - 2Document7 pagesDoina Petrescu - 2Raf FisticNo ratings yet

- Ideogram 11.21.11Document1 pageIdeogram 11.21.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Article 11.21.11Document22 pagesArticle 11.21.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Bibliography: CCA March Research Lab Fall 2011 Instructor: Neal SchwartzDocument2 pagesBibliography: CCA March Research Lab Fall 2011 Instructor: Neal SchwartzsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Ideogram10 21 11Document1 pageIdeogram10 21 11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- IdeogramDocument1 pageIdeogramsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- 10.21.11 AbstractDocument1 page10.21.11 AbstractsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Findley Building ChangeDocument20 pagesFindley Building ChangesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- 10.21.11 AbstractDocument1 page10.21.11 AbstractsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Bibliography: CCA March Research Lab Fall 2011 Instructor: Neal SchwartzDocument2 pagesBibliography: CCA March Research Lab Fall 2011 Instructor: Neal SchwartzsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Article: Bufalini Map of Rome, 1551 Source:nolli - Uoregon.eduDocument10 pagesArticle: Bufalini Map of Rome, 1551 Source:nolli - Uoregon.edusfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- 10.6.11 AbstractDocument1 page10.6.11 AbstractsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Article 10.6.11Document4 pagesArticle 10.6.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

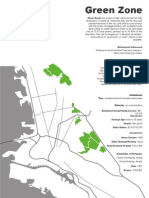

- Green ZoneDocument1 pageGreen ZonesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

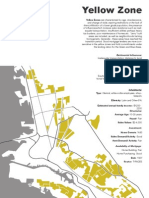

- Yellow ZoneDocument1 pageYellow ZonesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- IdeogramDocument1 pageIdeogramsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Sites of MemoryDocument3 pagesSites of MemorysfwhitehornNo ratings yet

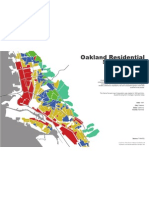

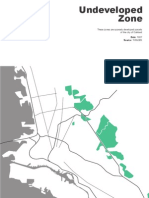

- Redline + Zones+ DataDocument6 pagesRedline + Zones+ DatasfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Redline BaseDocument1 pageRedline BasesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- White Papers, Black MarksDocument2 pagesWhite Papers, Black MarkssfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Light Blue ZoneDocument1 pageLight Blue ZonesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Blue ZoneDocument1 pageBlue ZonesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

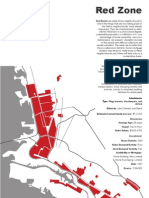

- Red ZoneDocument1 pageRed ZonesfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Whitehorn - Shawn 9.22.11Document1 pageWhitehorn - Shawn 9.22.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- The American Ghetto SummaryDocument2 pagesThe American Ghetto SummarysfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- SWhitehorn - Thesis Abstract 9.7.11Document2 pagesSWhitehorn - Thesis Abstract 9.7.11sfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Miami's Colored Over SegregationDocument2 pagesMiami's Colored Over SegregationsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument1 pageBibliographysfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- Metropolitcs Sum and CritDocument2 pagesMetropolitcs Sum and CritsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument1 pageAbstractsfwhitehornNo ratings yet

- MBA Capstone Module GuideDocument25 pagesMBA Capstone Module GuideGennelyn Grace PenaredondoNo ratings yet

- Airline Operation - Alpha Hawks AirportDocument9 pagesAirline Operation - Alpha Hawks Airportrose ann liolioNo ratings yet

- Different Western Classical Plays and Opera (Report)Document26 pagesDifferent Western Classical Plays and Opera (Report)Chaorrymarie TeañoNo ratings yet

- The Wisdom of Solomon by George Gainer Retyped 1nov16Document47 pagesThe Wisdom of Solomon by George Gainer Retyped 1nov16kbsd3903No ratings yet

- Attestation Process ChecklistDocument2 pagesAttestation Process Checklistkim edwinNo ratings yet

- Matthew 13 Parable of The Pearl of Great PriceDocument3 pagesMatthew 13 Parable of The Pearl of Great PriceMike SpencerNo ratings yet

- Psu Form 111Document2 pagesPsu Form 111Ronnie Valladores Jr.No ratings yet

- AZ 104 - Exam Topics Testlet 07182023Document28 pagesAZ 104 - Exam Topics Testlet 07182023vincent_phlNo ratings yet

- Cease and Desist DemandDocument2 pagesCease and Desist DemandJeffrey Lu100% (1)

- Module 6 ObliCon Form Reformation and Interpretation of ContractsDocument6 pagesModule 6 ObliCon Form Reformation and Interpretation of ContractsAngelica BesinioNo ratings yet

- Exercise of Caution: Read The Text To Answer Questions 3 and 4Document3 pagesExercise of Caution: Read The Text To Answer Questions 3 and 4Shantie Susan WijayaNo ratings yet

- 50 Compare Marine Insurance and General InsuranceDocument1 page50 Compare Marine Insurance and General InsuranceRanjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- Installation and repair of fibre optic cable SWMSDocument3 pagesInstallation and repair of fibre optic cable SWMSBento Box100% (1)

- Niela Marie H. - GEC105 - SLM7 - MPHosmilloDocument4 pagesNiela Marie H. - GEC105 - SLM7 - MPHosmilloNiela Marie HosmilloNo ratings yet

- Baker Jennifer. - Vault Guide To Education CareersDocument156 pagesBaker Jennifer. - Vault Guide To Education Careersdaddy baraNo ratings yet

- Rabindranath Tagore's Portrayal of Aesthetic and Radical WomanDocument21 pagesRabindranath Tagore's Portrayal of Aesthetic and Radical WomanShilpa DwivediNo ratings yet

- Final Project Taxation Law IDocument28 pagesFinal Project Taxation Law IKhushil ShahNo ratings yet

- What's New?: Changes To The English Style Guide and Country CompendiumDocument40 pagesWhat's New?: Changes To The English Style Guide and Country CompendiumŠahida Džihanović-AljićNo ratings yet

- VisitBit - Free Bitcoin! Instant Payments!Document14 pagesVisitBit - Free Bitcoin! Instant Payments!Saf Bes100% (3)

- 2003 Patriot Act Certification For Bank of AmericaDocument10 pages2003 Patriot Act Certification For Bank of AmericaTim BryantNo ratings yet

- Your Guide To Starting A Small EnterpriseDocument248 pagesYour Guide To Starting A Small Enterprisekleomarlo94% (18)

- March 3, 2014Document10 pagesMarch 3, 2014The Delphos HeraldNo ratings yet

- Home Office and Branch Accounting (GENERAL)Document19 pagesHome Office and Branch Accounting (GENERAL)수지No ratings yet

- B001 Postal Manual PDFDocument282 pagesB001 Postal Manual PDFlyndengeorge100% (1)

- Y-Chromosome Analysis in A Northwest Iberian Population: Unraveling The Impact of Northern African LineagesDocument7 pagesY-Chromosome Analysis in A Northwest Iberian Population: Unraveling The Impact of Northern African LineagesHashem EL-MaRimeyNo ratings yet

- Law&DevelopmentDocument285 pagesLaw&Developmentmartinez.ortiz.juanjoNo ratings yet

- RoughGuide之雅典Document201 pagesRoughGuide之雅典api-3740293No ratings yet

- Philippine LiteratureDocument75 pagesPhilippine LiteratureJoarlin BianesNo ratings yet

- Simic 2015 BR 2 PDFDocument23 pagesSimic 2015 BR 2 PDFkarimesmailNo ratings yet

- Taiping's History as Malaysia's "City of Everlasting PeaceDocument6 pagesTaiping's History as Malaysia's "City of Everlasting PeaceIzeliwani Haji IsmailNo ratings yet