Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 3 FTC Holder Notice Triggers Bank's Class Liability PL94Ch03

Uploaded by

Charlton ButlerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 3 FTC Holder Notice Triggers Bank's Class Liability PL94Ch03

Uploaded by

Charlton ButlerCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 3

3.1 Complaint

FTC Holder Notice Triggers Bank's Class Liability for Dealer's Fraud

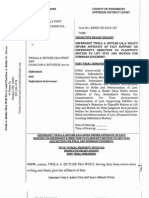

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO JOHNSON, VEGA, RODRIGUEZ, NORRELL, NORRELL, DURAN, and SEILER Individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated, Plaintiffs, [vs.] FIRST NATIONAL BANK IN ALAMOGORDO, THE CAR LOT, INC., a New Mexico Corporation, DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Sr., DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Jr., and SALLY BURNS, Defendants. No. CIV 89-1137 HB SIX PERSON JURY DEMANDED

FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT PRELIMINARY STATEMENT This is a class action, instituted by Plaintiffs on behalf of themselves and all other persons similarly situated, brought in accordance with and to remedy the violations of the Federal Motor Vehicle Information and Costs Savings Act, 15 USC, Sections 1901, 1981-1991 (hereinafter "the Odometer Act"), and Department of Transportation Regulations, 49 CFR Sections 580.1-.7, as well as pendent State claims. During the previous two years Plaintiffs purchased used motor vehicles from Defendant The Car Lot, Inc. (hereinafter "Car Lot"), a used car dealer located in Alamogordo, New Mexico, a sham corporation owned entirely by Defendants Burnses (hereinafter collectively referred to as the "Dealer Defendants"). In the course of the sales transaction, the Dealer Defendants rolled-back the odometers on the vehicles and affirmatively misrepresented the true odometer readings as part of their malicious, criminal and intentional scheme to defraud Plaintiffs and the class which they represent. The cars were sold on credit using installment contracts which were assigned to Defendant First National Bank in

Alamogordo (hereinafter "Bank"), which is subject to all claims and defenses which Plaintiffs may assert against the Dealer Defendants. Through the conduct of a criminal investigation and subsequent prosecution conducted by the Alamogordo Department of Public Safety, it now has been established that the Plaintiffs were a group of no fewer than one hundred and nine consumers who purchased used vehicles from or through the Dealer Defendants and whose odometers were similarly fraudulently altered. A substantial number of these victims are installment purchasers whose financing contracts were also purchased by Defendant Bank under the identical terms and conditions subjecting Defendant Bank to liability for the claims and defenses which maybe asserted against the Dealer Defendants, The class represented by Plaintiffs is comprised of each of these victims of the fraudulent scheme in which the Bank participated as the financing entity, On behalf of themselves and the class which they represent, Plaintiffs seek hereby to recover actual, statutory, and punitive damages, plus reasonable attorney's fees, to compensate them for their losses and to deter Defendants from so acting in the future. JURISDICTION

1. Jurisdiction of this Court attains pursuant to 15 USC Section 1989(b), 28 USC Section 1337, and the doctrine of pendent jurisdiction. PARTIES 2. Plaintiffs, Tracy Johnson, Kumae Vega, Ancieto S. Rodriguez, Craig Norrell, Lori Norrell, Ruth Duran, and Eloisa Seiler, are natural persons who reside in New Mexico, and each is a "transferee" as defined by 49 CFR Section 580.3. Plaintiffs bring this action on behalf of themselves individually and as the class representatives of all persons similarly situated. 3. Defendant Bank is a national bank whose principal place of business is located in Alamogordo, New Mexico.

4. Defendant Car Lot is a New Mexico corporation which, at all times relevant hereto, engaged in the business of a used car dealer in Alamogordo, New Mexico and is a "transferor" as defined by 49 CFR Section 580.3. 5. Defendant Douglas Ray Burns, Sr., is a natural person who resides in Otero County, New Mexico, and who at all times relevant hereto has been the president of Defendant Car Lot. 6. Defendant Sally Burns is a natural person who resides in Otero County, New Mexico and who at all times relevant hereto has been the vice-president, secretary, and treasurer of Defendant Car Lot and the wife of Defendant Douglas Burns. 7. Defendant Douglas Ray Burns, Jr., is the son of Defendant Douglas Ray Burns, Sr., and Sally Burns, and at times relevant hereto has been a principal actively involved in the operation of Defendant Car Lot. CLASS ACTION ALLEGATIONS 8. This action is maintained as a class action on behalf of the following described class: All persons who, commencing two years before the date of filing of the Complaint in this action, have purchased a used motor vehicle from the Dealer Defendants, the odometer in whose vehicles was altered and who received odometer disclosure statements in violation of the Federal Odometer Act, and who purchased the vehicle through an installment contract assigned to Defendant Bank. 9. This action is appropriately maintained as a class action as the class is so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable, there are questions of law or fact common to the class, the claims or defenses of the representative party are typical of the claims or defenses of the class, the representative party will thoroughly and adequately protect the interests of the class, and all appropriate elements of Rule 23(b), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, are present. FACTUAL ALLEGATIONS 10. Within the past two years, Plaintiffs purchased used motor vehicles from the Dealer Defendants through sales documents, true and correct copies of which are attached hereto and incorporated herein as Exhibits A, B, C, D, and E [not reprinted infra].

11. Included in the documentation which they executed were installment contracts which were immediately or shortly thereafter assigned to Defendant Bank, which, pursuant to the terms of the contracts, "is subject to all claims and defenses which the debtor could assert against the seller of good or services obtained pursuant hereto or with the proceeds hereof." 12. Between the time when the Dealer Defendants came into possession of the used vehicles and their sale to Plaintiffs, the Dealer Defendants altered the odometer readings on the vehicles, rolling back the odometers to a number substantially less than their actual mileage. 13. With the intent to defraud, the Dealer Defendants then provided to Plaintiffs at the time of the sale of the. vehicles disclosures which inaccurately stated the mileage of the vehicles, misrepresented their condition and use, and otherwise violated the requirements of the Federal Odometer Act. 14. The Defendants Burnses with the intent to defraud, personally and individually participated in the tampering and altering of the odometers and otherwise conspired with each other to engage in a campaign of illegal and fraudulent practices involving the tampering and altering of odometers in the sale of used motor vehicles. 15. From October 1988 through February 1989, the Alamogordo Department of Public Safety conducted a criminal investigation involving allegations that the Dealer Defendants had engaged in said campaign of illegal and fraudulent practices, involving the tampering and altering of odometers in the sale of used motor vehicles. A true and correct copy of that report, or a least a portion thereof, is attached hereto and incorporated herein as Exhibit F [not reprinted infra]. 16. That criminal investigation determined that no fewer then one hundred and nine persons were the victims of this fraudulent scheme and purchased from the Dealer Defendants used motor vehicles whose odometers had been rolled back and whose true odometer readings were misstated.

17. Plaintiffs and each class member had no knowledge of the alteration of and tampering with the odometers on their used cars and naturally relied on the inaccurately disclosed information to their detriment. 18. Upon information and belief, a substantial percentage of these victims purchased their vehicles through installment financing using the identical form contracts which were assigned to Defendant Bank. 19. Upon information and belief, Defendant Car Lot is a closely held family corporation which exists in name alone and otherwise is a sham corporation for whose conduct Defendants Burnses are liable. 20. The foregoing acts and omissions were undertaken by the Dealer Defendants willfully, maliciously, intentionally, fraudulently and/or in gross or reckless disregard of the rights of Plaintiffs and the members of the class represented herein. 21. As a proximate result of the foregoing acts and omissions, Plaintiffs and the members of the class represented herein have suffered actual damage and injury comprised of, inter alia, the difference between the price paid for the motor vehicles purchased as low mileage vehicles and their actual value, and are entitled to recover compensatory damages in an amount to be proven at trial. 22. Defendants are liable to Plaintiffs and the members of the class represented herein for punitive damages in an amount to be proven at trial. CAUSES OF ACTIONS COUNT I 23. The foregoing acts and omissions constitute violations of the Federal Odometer Act. 24. In accordance with 15 USC Section 1989(a), Plaintiffs and each member of the class represented herein arc entitled to recover three times the amount of their actual damages sustained or $1,500.00, whichever is greater, together with reasonable attorneys' fees and costs.

COUNT II 25. The foregoing acts and omissions constitute unfair or deceptive and/or unconscionable trade practices made unlawful pursuant to the New Mexico Unfair Practices Act, Section 57-12-3 NMSA 1978. 26. Plaintiffs and each member of the class represented herein are entitled to recover their actual damages sustained, such damages trebled, plus reasonable attorneys' fees and costs, pursuant to Section 57-12-10. COUNT III 27. At all times relevant hereto, the Dealer Defendants owed to Plaintiffs and each member of the class represented herein the duty, inter alia, to provide accurate and complete information concerning the condition of the use vehicles purchased, not to misrepresent the condition or mileage of the vehicles purchased, and to deal with them honestly and in good faith. 28. The foregoing acts and omissions constitute breaches of those duties. 29. Plaintiffs and each member of the class represented herein are entitled to recover their actual damages and punitive damages in an amount to be proven at trial. COUNT IV 30. The foregoing acts and omissions constitute breaches of the contractual agreements and express warranties associated with the sale of each motor vehicle. 31. Plaintiffs and each member of the class represented herein are entitled to recover their actual damages and punitive damages in an amount to be proven at trial. JURY DEMAND Plaintiff hereby demands trial by a six person jury on all issues so triable. WHEREFORE, Plaintiffs pray that this Honorable Court grant the following relief: 1. Enter an order declaring that this action be maintained as a class action as defined herein. 2. Award Plaintiffs and each class member actual damages in an amount to be proven at trial.

3. Award Plaintiffs and each class member treble damages, but not less than $1,500.00 each. 4. Award Plaintiffs and each class member punitive damages in an amount to be proven at trial. 5. Award Plaintiffs and each class member reasonable attorneys' fees. 6. Award Plaintiffs and each class member their costs. 7. Grant such other and further relief as may be just and proper. Respectfully submitted, Attorneys for Plaintiffs

3.2

Plaintiff's First Set of Interrogatories

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO

JOHNSON, VEGA, RODRIGUEZ, NORRELL, NORRELL, DURAN, and SEILER Individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated, Plaintiffs, [vs.] FIRST NATIONAL BANK IN ALAMOGORDO, THE CAR LOT, INC., a New Mexico Corporation, DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Sr., DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Jr., and SALLY BURNS, Defendants. No. CIV 89-1137 HB

PLAINTIFFS' FIRST SET OF INTERROGATORIES

TO: Defendant First National Bank in Alamogordo.

You are hereby requested to fully answer the following Interrogatories in the spaces provided in the specified detail, in writing and under oath within the time and in the manner provided by Rule 33 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. If you need additional space, please continue your answers on pages that you attach to this document in which you identify the specific interrogatory answers you are continuing. You may, instead of answering all or part of the information requested in the spaces provided, attach legible copies of relevant documents in response to any interrogatory, but only if all of the information requested is in them and the interrogatory is identified to which the documents are responsive. Each interrogatory should be answered pursuant to the definitions provided below and with information available as of the date of your Answers. Please remember that you should answer with all of the information within your personal knowledge, custody or control, or in the control of your agents, and with all information you can discover by making a reasonable inquiry. DEFINITIONS 1. "Document" means any tangible record, words or data in your possession, custody or control, whether written down, recorded, reproduced visually or reproduced some other way. This includes but is not limited to correspondence, notes, insurance appraisals or lists, written contracts, deeds, leases, agreements of any kind or memoranda of agreements, stock certificates, bankbooks, check records and checks, title documents, financial statements, tax returns, wage records and ;lips, bills, account statements, photographs, insurance lists and inventories, and reports of any kind. 2. "Identify" or "describe" when referring to a person, a firm, a corporation, or another entity shall mean to state the full formal name; the address of the principal place of business or residence; and the telephone number.

3. "Identify" or "describe" when referring to a document shall mean giving a description of the title, the author, a description of the general subject matter and the identity and address of its present custodian. INTERROGATORIES INTERROGATORY NO. 1: Please state the name, business and home addresses and telephone numbers, and position of the person(s) responding hereto, the authority by which such person(s) is so acting on behalf of the Defendant, and the name, home and work addresses and telephone numbers, and position of each person consulted in the preparation of the answers to these interrogatories. ANSWER:

INTERROGATORY NO. 2: Identify each document consulted or reviewed in preparing the answers to these interrogatories. ANSWER:

INTERROGATORY NO. 3: State whether there is any insurance agreement under which any person carrying on an insurance business may be liable to satisfy part or all of the judgment which may be entered in this action or to indemnify or reimburse for payments made to satisfy any judgment which may be entered in this action, and identify all documents reflecting the existence of such insurance agreement. ANSWER:

INTERROGATORY NO. 4: State whether you are or have been since October 1, 1987 the assignee or holder of any installment contract or similar instrument which finances the purchase by any person of a used motor vehicle sold by the Car Lot Inc., Douglas Ray Burns Sr., or Sally Burns or the proceeds of which were used by any person to purchase a used motor vehicle from the Car Lot Inc., Douglas Ray Burns Sr., or Sally Burns, and if so, identify each

such installment contract or instrument and all other documents related to or reflecting said sale or financing and identify each such person. ANSWER:

INTERROGATORY NO. 5: Regarding each of the one hundred and nine persons listed as victims in the Report attached to the Complaint herein as Exhibit B [not reprinted infra], state whether you are or have been since October 1, 1987 the payee, assignee, or holder of any installment contract, loan document, or other similar instrument in which such person is the payor or obligator, and if so, identify each such installment contract, loan document, or other such instrument. ANSWER:

INTERROGATORY NO. 6: State a) the date when you first received an assignment of any installment contract or similar instrument from the Car Lot Inc., Douglas Ray Burns, Sr., or Sally Burns, b) the number of such assignments which you have received since that date, and c) whether such assignment(s) is with or without recourse, and identify each document related to or reflecting any agreements or other contractual undertaking of any kind between you and the Car Lot Inc., Douglas Ray Burns, Sr., or Sally Burns. ANSWER:

INTERROGATORY NO. 7: State when you or any person acting in your employ or on your behalf first became aware or otherwise learned of any allegation that the Car Lot Inc., Douglas Ray Burns, Sr., or Sally Burns was or had been engaging in activities involving odometer tampering or alterations, describe the circumstances of so learning of those allegations, identify the person(s) so acting in. your employ or on your behalf, and describe in detail and with particularity the action, if any, taken by you upon learning of said allegations. ANSWER:

INTERROGATORY NO. 8: State whether you or any person acting in your employ or on your behalf has had any contact or communication of any nature since October 1, 1987, with the Car Lot Inc., Douglas Ray Burns, Sr., or Sally Burns or any person acting in their employ or on their behalf, and if so, identify each such person and state the date, nature, circumstances, and substance of each such contact or communication. ANSWER:

INTERROGATORY NO. 9: State with detail and particularity the factual and/or legal basis for each affirmative defense which you have raised or are raising in your Answer to Complaint herein. ANSWER:

INTERROGATORY NO. 10: To the extent not previously done, identify all documents relevant, related to, or reflecting any aspect of your dealings with the Car Lot, Inc., Douglas Ray Burns, Sr., Sally Burns, or any person who has purchased a used motor vehicle from your co-defendants herein since October 1, 1987. ANSWER: Respectfully submitted, Attorneys for Plaintiffs

3.3

Motion For Conditional Class Certification

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO

JOHNSON, VEGA, RODRIGUEZ, NORRELL, NORRELL, DURAN, and SEILER Individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated, Plaintiffs,

[vs.] FIRST NATIONAL BANK IN ALAMOGORDO, THE CAR LOT, INC., a New Mexico Corporation, DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Sr., DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Jr., and SALLY BURNS, Defendants. No. CIV 89-1137 HB MOTION FOR CONDITIONAL CLASS CERTIFICATION COME NOW Plaintiffs, by and through their undersigned counsel, and pursuant to Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, move this Court to issue an Order conditionally certifying the herein cause as a class action defined as follows: All persons who have purchased a used motor vehicle from the Dealer Defendants, the odometer in whose vehicle was altered, who received odometer disclosure statements in violation of the Federal Odometer Act, who discovered said violation within two years before the date of filing of the Complaint in this action, and who purchased the vehicle through an installment contract assigned to Defendant Bank.

For their reasons therefore, Plaintiffs state as follows: 1. The requirements of Rule 23(a) and (b) are met. 2. Plaintiff's refer to their Memorandum in Support hereof filed herewith. Concurrence of opposing counsel has been sought and denied. Attorneys for Plaintiffs

3.4

Memorandum In Support For Conditional Class Certification

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO JOHNSON, VEGA, RODRIGUEZ, NORRELL, NORRELL, DURAN, and SEILER Individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated, Plaintiffs, [vs.] FIRST NATIONAL BANK IN ALAMOGORDO, THE CAR LOT, INC., a New Mexico Corporation, DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Sr., DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Jr., and SALLY BURNS, Defendants. No. CIV 89-1137 HB

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT FOR CONDITIONAL CLASS CERTIFICATION

I. INTRODUCTION

This action is instituted in accordance with and to remedy the violations of the Federal Motor Vehicle Information and Costs Savings Act, 15 U.S.C. Sections 1902, 1981- 1991 (hereinafter "the Odometer Act"), and Department of Transportation Regulations, 49 C.F.R. Sections 580.1-.7, as well as pendent state claims based on the identical illegal conduct giving rise to the action under the Odometer Act. As stated with greater particularity in the First Amended Complaint and Memorandum in Support of Motion for Partial Summary Judgment

filed herewith, the Dealer Defendants are alleged to have a engaged in the routine, regular, and intentional practice of selling used automobiles whose odometers were fraudulently and illegal altered and rolled back in violation of federal and state law. Plaintiffs now seek conditional class certification to enforce their statutory and common law remedies against these Defendants as well as their co-Defendant, the Bank which financed the automobile purchases. The evidence developed at this initial state of discovery and of the proceedings generally reveals that the dealer defendants routinely purchased in wholesale transactions late model used cars with high mileage and rolled back the odometers to show mileage of less than 50,000 miles. The class is comprised of all persons who have purchased a used motor vehicle from the Dealer Defendants, the odometer in whose vehicles was altered, who received odometer disclosure statements in violation of the Federal Odometer Act, who discovered said violation within two years before the date of filing of the Complaint in this action, and who purchased the vehicle through an installment contract assigned to the Defendant Bank.1 Particularly because of the routine, random, and indiscriminate nature of the illegal conduct by the Dealer Defendants and of the financing arrangement organized by the Defendant Bank, class certification under Rule 23 is now appropriate.

As a result of the initial discovery undertaken in this case, Plaintiffs have now revised their definition of the putative class so as to include the 68 persons whose used car purchases predated the filing of the Complaint by more than two years but who naturally were unaware of the odometer tampering until the entire scheme was publicized by institution of the criminal investigation by the Alamogordo Department of Public Safety. The case law in unanimous that the two-year statute of limitations under the Federal Odometer Act [15 U.S.C. Section 1989(b)] is tolled until the purchaser discovers the violation or should have discovered it. State v. B & H Auto, 701 F. Supp. 201 (D. Utah 1988); Jones v. Ray Stanley Chevrolet, 666 F. Supp. 194 (D. Mont. 1987); Cwiakala v. Economy Auto, Inc., 587 F. Supp. 1462 (N.D. Ind. 1984); Byrne v. Autohaus on Edens, Inc., 488 F. Supp. 276 (N.D. Ill. 1980); and Levine v. MacNeil, 428 F. Supp. 675 (D. Mass. 1977). As these cases make clear, the purchaser of a used automobile with a rolled back odometer is in no position to discover the violation absent extraordinary circumstances. The Defendant Bank has stated in its Answers to Interrogatories that it only discovered the odometer tampering in October 1988, one year prior to the filing of the Complaint here, through the newspaper publicity accompanying that criminal investigation. The members of the putative plaintive class certainly were in to better position to make this discovery that the Bank which dealt regularly and often with the Car Lot, Inc. Therefore, none of the potential 114 plaintiffs have claims which cannot be asserted.

It is of course axiomatic that the Court may not inquire into the merits of this litigation in evaluating the appropriateness of class certification. Kahan v. Rosenstiel, 424 F.2d 161, 169 (3rd Cir.), cert. denied 398 U.S. 950 (1970), and Doctor v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company, 540 F.2d 699, 706-709 (4th Cir. 1976). On the other hand, some inquiry into the nature of the claims and the evidence which likely will be introduced at trial is in inevitable to permit the Court to determine if the elements of Rule 23 have been met. Id. Class certification cannot be considered in a vacuum, as, for example, proof of the typicality of the claims necessarily involves a review of the nature of the illegal conduct alleged. Id. Plaintiff's seek conditional class certification for the simple and practical reason that additional discovery and case development will be necessary in order to identify each of the putative class members and otherwise present a complete analysis of the scope of the class. Discovery to date has revealed that a total of 114 used car purchases from the Car Lot Inc. were financed by the Defendant Bank, 22 of whom arc persons whom the Alamogordo Department of Public Safety has already identified as victims of the scheme in its Criminal Case Report attached to the First Amended Complaint herein. While additional discovery carries with it the possibility that this universe may increase, Plaintiff's have no reason to question the good faith or thoroughness of the Bank's search of its records and production of its consumer files identifying this group of consumers who meet the threshold definition of the class. Nevertheless, Plaintiffs recognize that a precise count cannot be provided without further case development. Under the circumstances, additional class certification is appropriate in order to meet the following specific requirement of Rule 23(c)(1): As soon as practicable after the commencement of an action brought as a class action, the court shall determine by order whether it is to bc so maintained. An order under this subdivision maybe conditional, and maybe altered or amended before the decision on the merits.

So certifying the class now, when Plaintiff's can meet their burden as a threshold matter on all required elements, is appropriate and necessary in order to meet the practical purposes of Rule 23. Indeed, this Court has so recognized the utility of this procedure in the past. Padilla v. Stinger, 395 F.Supp. 495, 502 ( N.M. 1974) (Bratton, J.) (class subsequently decertified).

II. ARGUMENT OF LAW Plaintiffs now address seriatim each of the requirements of Rule 23 applicable here. As a class action for monetary relief, Plaintiffs will review each of the general requirements of Rule 23(a) and the specific requirements of Rule 23(b)(3) and demonstrate that each clement has been met. A. IMPRACTICABILITY OF JOINDER

Rule 23(a)(1) requires that "the class [be] so numerous the joinder of all members is impracticable." The standard of impracticality does not mean "impossibility" but only difficulty or inconvenience of joining all members of the class. Cypress v. Newport News General, 375 F.2d 648, 653 (4th Cir. 1967) (en banc). Critical to this analysis is the principle that the actual number of class members is relevant but not determinative. The issue is not the numerical size of the class but, as explicitly stated in Rule 23(a)(1), that joinder is impracticable. Hatisberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32, 41 (1941). The dispositive factors necessary to determine whether joinder is impracticable support certification. Courts have recognized that individuals are often reluctant to institute litigation against defendants with whom they remain in a continuing relationship. The overwhelming number of identified putative class members are still paying off the Bank under their installment contracts. Such creditors [Haynes v. Logan Furniture Mart, Inc., 503 F.2d 1161, 1165 (7th Cir. 1974)] as well as current employers [Ste. Marie v. Eastern Railroad Association, 72 F.R.D. 433, 449 (S.D.N.Y. 1976)] are precisely the types of defendants where the very nature of the relationship can impair individual joinder. The Seventh Circuit in Haynes observed the

following concerning the preferability of consumer class actions over individual litigation involving ongoing consumer-creditor relationships: The individual if aware at all of his claim under the Act is bound to have some reluctance to sue in his own name the supplier with whom he continues to do business and one who could bc in a position to visit harsh remedies on the buyer in the event of a subsequent default.

503 F.2d at 1165.

Another factor is the relatively small amount of the claims in relationship to the extraordinary costs of litigation in our society. Gas Service Company v. Coburn, 389 F.2d 831, 833 (10th Cir. 1968). Minimum recovery under the Federal Odometer Act is $1,500, and the maximum is three times actual damages. 15 U.S.C. Section 1989(a)(1). Plaintiffs anticipate that the difference between the used vehicles as low mileage cars as represented and their fair market values with correct odometer disclosures is in no case more than $1,000.00. The reality of odometer tampering litigation is simply that each individual claim does not promise to be great, and as a result individual joinder is correspondingly impracticable. Id.; Swanson v. American Consumer Industries, Inc., 415 F.2d 1326, 1333, n. 9 (7th Cir. 1969); Korn v. Franchard Corp., 456 F.2d 1206, 1209 (2nd Cir. 1972); Vernon J. Rockler and Company, Inc. v. Graphic Enterprises, lnc., 52 F.R.D. 335, 339 (D. Minn. 1971). Plaintiffs are by definition ordinary citizens who purchased used rather than new vehicles and were able to be swindled by an unscrupulous used car dealer. Another factor in determining impracticability of joinder is precisely this lack of knowledge and sophistication of the class members and their need for protection. Gordon v. Forsythe Company Hospital Authority Inc., 409 F.Supp. 708, 717 (M. D. N.C. 1976); Dolgow v. Anderson, 43 F.R.D. 472, 484-485 (E. D. N.Y. 1968). Such persons are unlikely to institute individual actions to vindicate their rights, and

only through maintaining this litigation as a class action will they receive the protections contemplated by Congress under the Federal Odometer Act. As to size, the class as now defined is well within the range approved by the federal courts. The following is a sampling of decisions under Rule 23 where a class has been certified of the general size presented here. Cypress v. Newport News General, supra, (18 class members); Manning v. Prinston Consumer Discount Compan, 390 F.Supp. 320, 324 (1975) (15 class members); Dale v. Electronics, Inc. v. RCL Electronics, Inc., 53 F.R.D. 531, 534 (D. N.H. 1971) (13 class members); Arkansas Education Association v. Board of Education, 446 F.2d 763, 765 (8th Cir. 1971) (20 class members); Wilmore v. City of Willington, 35 Fed. Rules Serv. 2d 591 (D. Del. 1982) (16 class members); MacNeal v. Columbine Exploration Corp., 123 FRD 181, 185 (E. D. Pa. 1988) (36 class members); Ballard v. Blue Shield of Southern West Virginia, Inc., 543 F.2d 1075, 1080 (4th Cir. 1976) (remand to consider certification for 45 class members); Sabala v. Western Gillette, Inc., 362 F.Supp. 1142, 1146-1147 (S.D. Tex. 1973) (26 class members). In view of the separate requirement of manageability discussed infra, the class presented here is of a size which is particularly appropriate under the totality of the circumstances. This joinder element should not be viewed so restrictively as to undermine the policies of class action litigation. Weaders v. Peter Reality Corp., 499 F.2d 1197, 1200 (6th Cir. 1974). Each of the factors discussed here have a cumulative effect, McMertery v. Burtness, 72 F.R.D. 450, 453 (D. Minn. 1976), and this Court has considerable flexibility in determining whether this element has been met. Cypress v. Newport News General, supra. In view of the purposes of class actions, (a) to achieve judicial economics and prevent multiplicity of suits (Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 333, 340 (10th Cir. 1975), (b) to deter multiple wrongs and fraud [Windham v. American Brands, Inc., 539 F.2d 1016, 1021 (4th Cir. 1976), Illinois v. Harper and Roe Publishers, Inc., 301 F.Supp. 484, 493 (N.D. Ill. 1969)), (c) to fulfill congressional policy in the area of consumer fraud [Haynes v. Logan Furniture Mark, Inc., supra.] and (d) and to provide a forum for small claimants and the uninformed [American Pipe and Construction Company v.

Utah, 414 U.S. 538, 551-552 (1974); Haynes v. Logan Furniture Mark, Inc., supra., 503 F.2d at 1164-1165], the impracticality of joinder element has been met. B. COMMON QUESTIONS OF LAW AND FACT Rule 23(a)(2) establishes the commonalty clement that there arc "questions of law or fact common to the class." The questions of law in this litigation are absolutely identical among the punitive plaintiff class members. In practical terms, the dispositive legal issue is the one addressed in Plaintiffs' Motion for Partial Summary Judgment which is being filed herewith and which seeks to establish the liability of the Bank as the financing entity from these transactions. There is no individual legal issue conceivable in that determination, and Plaintiffs' anticipate that no other separate legal questions will arise. The reason that the commonalty clement is met here is simply because none of the plaintiff class members was treated by the Defendants as individuals. While the Bank no doubt maintains its criteria of credit worthiness which were applied to the Plaintiffs, each by definition met those standards and received the purchase money loan for which application was made. At that point, each Plaintiff was treated in exactly the same manner as the Bank presumably treats each of its customers, including using the same form of contract. Kaminiski v. Shawmut Credit Union, 416 F. Supp. 1119, 1122-1123 (D. Mass. 1976). The Dealer Defendants were equally indiscriminate in their treatment of the Plaintiffs. There is no evidence that the Dealer Defendants had any personal animus towards any of their customers, and the only claim is that the Plaintiffs were the random victims of what was a common illegal scheme. Under these circumstances, the commonalty element is met. See In re Scientific Control Corporation Securities Litigation, 71 F.R.D. 491 (S.D.N.Y. 1976). Rule 23(a)(2) does not require that every single question of law or fact raised in the litigation must be common. Johnson v. American Credit Company of Georgia, 581 F.2d 526, 532 (5th Cir. 1978). The only issue of law or fact which may differ among the various plaintiffs is their measure of damages, since each automobile purchased necessarily had a different fair

market value and negotiated price. However, such an individualized issue docs not defeat class certification, as shown in Section II(E), infra. C. TYPICALITY Rule 23(a)(3) requires that "the claims or defenses of the representative parties are typical of the claims or defenses of the class..." For virtually the identical reasons discussed in the preceding Section, this element is also met. The named Plaintiffs were victimized in the same indiscriminate odometer tampering scheme as the class members and received financing for their automobile purchases under the identical terms and conditions as all others. As shown above, the only area in which any of the parties arc in any way different from the others is that each will be entitled to damages based on his/her individual circumstances. However, differences in the amount of damages sought will not render the claims atypical. Gas Service Company v. Coburn, supra, 389 F.2d at 833; City of New York v. General Motors Corp., 60 F.R.D. 393, 395 (S.D.N.Y. 1973); Clark v. Cameron-Brown Company, 72 F.R.D. 48, 60 (M.D. N.C. 1976). The typicality requirement demands only that Plaintiffs "demonstrate that there are other members of the class who have similar grievances." Wright v. Stone Container Corp., 524 F.2d 1058, 1062 (8th Cir. 1975). Here each of the Plaintiffs named as representatives assert the identical claims and requests for relief, and there can be no question that the typicality clement has been met. D. ADEQUACY OF REPRESENTATION Rule 23(a)(4) requires that "the representative parties will fairly and adequately protect the interests of the class." This element is generally characterized as an inquiry into whether the attorneys together with the named plaintiffs will act diligently on behalf of the class. Berland v. Mack, 48 F.R.D. 121. 127 (S.D.N.Y. 1969); Clark v. Cameron-Brown Company, supra., 72 F.R.D. at 54. Undersigned counsel are active practitioners whose combined experience and current diligence and commitment to this litigation will more than adequately protect the interests of the class. Mr. Sanders is the former District Attorney in the Twelfth Judicial District of New Mexico and is a practitioner with 16 years of trial litigation experience. Mr. Rubin has practiced

law in New Mexico for 15 years, virtually all of which has been spent representing claimants in consumer protection litigation; he is a nationally recognized expert in the area of consumer law, lectures regularly both in New Mexico and nationally in this substantive area, and has taught as an Adjunct Professor the Consumer Law course at the University of New Mexico School of Law. As a general rule, there is a presumption of competence for all members of the bar in good standing unless evidence to the contrary is adduced. Dolgow v. Anderson, supra., 43 F.R.D. at 496. Both counsel have appeared on numerous occasions before this Court and believe that this Court is in the best position to determine the adequacy element if challenged. As to the named Plaintiffs, the courts usually look simply to whether the representatives' interests are in any way antagonistic to or in conflict with those of the class members. Fowler v. Birmingham New Company, 608 F.2d 1055, 1058 (5th Cir. 1979). Such conflict must involve the subject matter of the suit and may not be minor or collateral. Berman v. Narragansett Racing Association, Inc., 414 F.2d 311, 317 (1st Cir. 1969), cert. denied 369 U.S. 1037; Vernon J. Rockler and Company v. Graphic Enterprises, Inc., supra., 52 F.R.D. at 342; Blackie v. Barrack, 524 F.2d 891, 908-910 (9th Cir. 1975). Furthermore, such conflict must be real and not speculative. Robertson v. NBA, 389 F. Supp. 867, 899 (S.D.N.Y. 1975). There is no conflict or antagonism whatsoever between the representatives and the class members. E. PREDOMINANCE AND MANAGEABILITY Rule 23(b)(3) requires that "the questions of law or fact common to the members of the class predominate over any questions affecting only individual members, and that a class action is superior to other available methods for the fair and efficient adjudication of the controversy." As discussed in Section II(B), supra, virtually all of the issues of law and fact are identical among the class members, and only the ultimate damage award for each Plaintiff will be different. Under these circumstances, the requirements of Rule 23(b)(3) are present. It is precisely because the claims of the Plaintiffs and the circumstances under which these claims arise are identical and because the method of proving damages will be exactly the same that the predominance and manageability elements have been met.

It is difficult to imagine any class action litigation where, absent a total unity of all issues of law and fact, a more manageable and typical case could be presented. The class is not so large that issues of proof will be difficult, and undersigned counsel intend to develop and present their evidence in the same manner that the Alamogordo Department of Public Safety undertook its investigation. Discovery has already disclosed the odometer readings at the time of sale for each of the 114 potential class members. A simple search of the public records will disclose the same information for each vehicle prior to its transfer to the Car Lot, Inc., and any reduction between the two figures will in essence establish Plaintiffs' substantive cases. For each sale with a rolled back odometer, Plaintiffs will hen present evidence of damages in the manner approved for establishing the difference between the price charged and the fair market value of the vehicle and its actual condition, through the usc of an expert witness relying on the NADA Official Used Car Guide (the "Blue Book") applicable at the time of sale. Kirkland v. Cooper, 438 F. Supp. 808, 811 (D.S.C. 1977). Actual damages will then be established, and treble damages will be awarded by a simple mathematical function. This Court has already determined that an individualized view of the damage determination is an insufficient basis on which to find lack of predominance, manageability or any other aspect required by Rule 23. Aquirre v. Bustos, 89 F.R.D. 645, 649 (D.N.M. 1981)(Bratton, J.) ("Only the amount of damages must be established individually, and this necessity alone cannot preclude class certification.") Even if this rule were not so, the simplicity of the formula to ascertain individual damages would mitigate any protracted individualized analysis. Providing notice to each of the putative class members, a responsibility which in particularly difficult cases may defeat manageability, The Society of Individual Rights, Inc. v. Hampton, 528 F.2d 905, 906 (9th Cir. 1975)(Per Curiam), will be no problem here. The Bank has already identified the potential class members from its records, and Plaintiffs now have the names and addresses of each of the parties who may be members of the class. Once the conditional certification sought here is granted, individual notice approved by this Court will be

sent by United States mail to each member. Again, a more manageable procedure is difficult to imagine. III. CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, the Plaintiff class should be conditionally certified as defined in the First Amended Complaint. Respectfully submitted, Attorneys for Plaintiffs

3.5

Reply Memorandum In Support of Motion For Conditional Class Certification

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO

JOHNSON, VEGA, RODRIGUEZ, NORRELL, NORRELL, DURAN, and SEILER Individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated, Plaintiffs, [vs.] FIRST NATIONAL BANK IN ALAMOGORDO, THE CAR LOT, INC., a New Mexico Corporation, DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Sr., DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Jr., and SALLY BURNS, Defendants. No. CIV 89-1137 HB

REPLY MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR CONDITIONAL CLASS CERTIFICATION Only the Defendant First National Bank in Alamogordo (the "Bank") has filed a pleading in opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion For Conditional Class Certification, and as a result the remaining Defendants are deemed to have consented to its granting in accordance with Local Rule 7.8. As to the Bank, its opposition appears to bc primarily founded on its misapprehension of the class definition based on its misreading of both the First Amended Complaint as well as the Motion For Conditional Class Certification and supporting Memorandum. The Bank erroneously states that "the [Amended] Complaint alleges that Defendant Bank is responsible to all one hundred and nine (109) purchasers listed in the police reports attached to the [Amended] Complaint." (Motion To Deny Certification of Class Action, para. 1). In both the Amended Complaint (para. 7), the Motion For Conditional Class Certification (recitation of class definition), and the Memorandum In Support For Conditional Class Certification (page 2), Plaintiffs have stated directly and in no uncertain terms that the class represented here is limited to those victims of the odometer fraud "who purchased the vehicle through an installment contract assigned to the Defendant Bank." Plaintiff does not know on what basis the Bank has so misconstrued the scope of this litigation. In any event, the Plaintiff class is comprised solely of parsons who financed their used car purchases with this Bank, and as a result each of the named Plaintiffs is representative of the class as a whole. Building on its misreading of the class definition, the Bank represents that only 24 persons (those persons listed in the police report whose contracts were assigned to the Bank) will be members of this class. To the contrary, discovery has revealed 114 used car vehicle purchases from the Car Lot, Inc. where the purchase contract was assigned to the Bank. The Bank has chosen to ignore this fact, and Plaintiff can therefore add nothing in this regard to her previously filed Memorandum. Plaintiffs would point out, however, that Ms. Kumae Vega, one of the seven named Plaintiffs, is not a person listed on the police report; and while the Bank has made no

effort to show or even suggest that the Plaintiffs are not representative .of the class insofar as the 92 potential class members who are not so noted on the police report, NU. Vega provides additional representation of the full breadth of the putative class. Without argument or citation to authorities, the Bank emphasizes that "some of the contracts included additional financing for license - registration, other fees and credit life which are not a part of damages to be claimed for misrepresentation of rolled-back odometers." (Memorandum, pps. 2-3). This quoted statement is accurate, but it has no bearing on the instant Motion. The Bank does not argue that individual aspects of the specific underlying transactions which are irrelevant to the claims of the class can in any way defeat class certification, and Plaintiffs have no reply to this non-issue. Finally, the Bank suggests that class certification is inappropriate here since the claims involve fraud. On the other hand, the Bank states that "perhaps a class action against the Defendants the Car Lot, Inc. and Burns, is suitable." (Memorandum, p. 2). This concession is entirely inconsistent with the Bank's affirmative position since the elements of proof are identical against both the Bank and its co-Defendants. More important, there is no rule in federal class action practice which holds that class certification is inappropriate in actions involving fraud. To the contrary, federal courts routinely certify such classes. Esplin v. Hirschi, 402 F.2d 94, 98-100 (10th Cir. 1968; Korn v. Franchard, Corp., 456 F.2d 1206, 1212-1213, and nn. 15-19 (2nd Cir. 1972) (certifying class over defendants' objection that "each member of the class will have to prove his individual reliance"); Blackie v. Barrack, 524 F.2d 891, 906, n. 22 (9th Cir. 1975) (reliance may bc inferred from materiality of misrepresentation and related circumstances); Harris v. Palm Springs Alpine Estates, Inc., 329 F.2d 909, 913-915 (9th Cir. 1974); Ramsey v. Arata, 406 F. Supp. 435, 441 (N.D. Tex. 1975) (class certified in securities fraud action despite individual questions of reliance and statute of limitations); Lorber v. Beebe, 407 F. Supp. 279, 294 (S.D. N.Y. 1975) (reliance may be inferred from proof of a "scheme to defraud."); Weiss v. Drew National Corporation, 71 F.R.D. 429, 430-431 (S.D. N.Y. 1976); Muth v. Dechert, Price, and Rhoads, 70 F.R.D. 602, 607,

n. I (E.D. Pa. 1976). Even oral misrepresentations directed to a putative class do not constitute such a predominance of individual issues so as to bar certification. Davis v. Avco Corporation, 371 F. Supp. 782, 792 (N.D. Ohio 1974); In Re Penn Central Securities Litigation, 347 F. Supp. 1327, 1344-1345 (E.D. Pa. 1972), aff'd, 494 F.2d 528 (3rd Cir. 1974); Byrnes v. IDS Realty Trust, 70 F.R.D. 608, 612-613 (D. Minn. 1976); Mills v. Roanoke Independent Loan and Thrift, 70 F.R.D. 448, 453 (W.D. Va. 1975); Ramsey v. Arata, supra, 406 F. Supp. at 440. Where, as here, the fraudulent representations are made in writing, a fortiori the class is appropriate for certification. Omitted from the Bank's discussion is the fact that members of the putative class will be entitled to relief under the Odometer Act even if they cannot prove reliance or otherwise prove that they suffered actual damage. In Delay v. Hearn Ford, 373 F. Supp. 791 (D.S.C. 1974), the court held that the minimum statutory recovery available under 15 U.S.C. Section 1989(a)(1) requires an award of $1,500 to any purchaser who proves a violation of the Act, regardless of reliance, knowledge, or injury. To this extent, the individual circumstances of the class members will not be an issue at all. Plaintiffs have proposed a relatively simple and straight forward formula for establishing the individual actual damages to be proven, if needed. (Memorandum, p. 11). The Bank has chosen not to comment in this regard and has cited not a single federal court decision supporting its position. Indeed, to accept the Bank's position would necessarily establish a rule that class actions may not be maintained in the federal courts where fraud is alleged. There is no such rule, and to the extent that particularly complex, individualized, and multi-faceted fraud claims may on occasions bar certification, there is no basis on which to find that this is such a case. This case represents a single scheme to defraud multiple victims through a common practice of criminal behavior, and class certification is therefore appropriate. Respectfully submitted, Attorneys for Plaintiffs

3.6

Proposed Order Granting Conditional Class Certification

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO JOHNSON, VEGA, RODRIGUEZ, NORRELL, NORRELL, DURAN, and SEILER Individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated, Plaintiffs, [vs.] FIRST NATIONAL BANK IN ALAMOGORDO, THE CAR LOT, INC., a New Mexico Corporation, DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Sr., DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Jr., and SALLY BURNS, Defendants. No. CIV 89-1137 HB

(Proposed) ORDER GRANTING CONDITIONAL CLASS CERTIFICATION

THIS MATTER having come to be considered at the hearing held on November 27, 1990, upon Plaintiffs' Motion For Conditional Class Certification, Plaintiffs having appeared by their attorney, Richard J. Rubin, Defendant First National in Alamogordo having appeared by its attorney, Norman L. Gagne, the Defendants having received notice and having not appeared, the Court considered the evidence presented and the legal argument of the parties, being fully advised in the premises, and otherwise for good cause shown, FINDS: Each of the elements of Rule 23(a) and (b)(3) have been established and are present and the Plaintiff class should be conditionally certified.

WHEREFORE, IT IS ORDERED that the Motion For Conditional Certification be and hereby is granted and the Plaintiff class be and hereby is conditionally certified as follows: All persons who have purchased a used motor vehicle from the Dealer Defendants, the odometer in whose vehicle was altered, who received odometer disclosure statements in violation of the Federal Odometer Act, who discovered said violation within two years before the date of filing of the Complaint in this action, and who purchased the vehicle through an installment contract assigned to Defendant Bank. IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that counsel for Plaintiffs shall submit to the Court, after conferring with counsel for the Defendant Bank, a proposed notice in accordance with Rule 23(c)(2). UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

Submitted by: Attorney for Plaintiffs

Approved as to form: Attorney for Defendant Bank

3.7

Motion For Partial Summary Judgment

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO

JOHNSON, VEGA, RODRIGUEZ, NORRELL, NORRELL, DURAN, and SEILER Individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated, Plaintiffs, [vs.]

FIRST NATIONAL BANK IN ALAMOGORDO, THE CAR LOT, INC., a New Mexico Corporation, DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Sr., DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Jr., and SALLY BURNS, Defendants. No. CIV 89-1137 HB

MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT COME NOW Plaintiffs, by and through their undersigned counsel, and pursuant to Rule 56, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, hereby move this Court to issue an Order granting them partial summary judgment declaring that, as a matter of law, Defendant First National Bank in Alamogordo ("Bank") is liable for the acts and omissions of its co-Defendants constituting violations of the Federal Motor Vehicle Information and Costs Savings Act, 15 U.S.C. Section 1901, 1981-1999 (hereinafter "the Odometer Act"), Department of Transportation Regulations promulgated thereunder, 49 C.F.R. Sections 580.1-.7, and the related state consumer fraud claims. For their reasons therefor, Plaintiffs state as follows: 1. Concerning this narrow issue of the Bank's liability, no material issues of fact are in dispute, and Plaintiffs are entitled to partial summary judgment so declaring the Bank's liability as a matter of law. 2. Plaintiffs further refer to their Memorandum in Support hereof filed herewith. Concurrence of opposing counsel has been sought and denied.

Respectfully submitted, Attorneys for Plaintiffs

3.8

Memorandum In Support of Motion For Partial Summary Judgment

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO

JOHNSON, VEGA, RODRIGUEZ, NORRELL, NORRELL, DURAN, and SEILER Individually and on behalf of all other persons similarly situated, Plaintiffs, [vs.] FIRST NATIONAL BANK IN ALAMOGORDO, THE CAR LOT, INC., a New Mexico Corporation, DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Sr., DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Jr., and SALLY BURNS, Defendants. No. CIV 89-1137 HB

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT

I. INTRODUCTION

This is a class action instituted by Plaintiffs on behalf of themselves and all other persons similarly situated, brought in accordance with and to remedy violations of the Federal Motor Vehicle Information and Costs Savings Act, 15 U.S.C. Sections 1901, 1981-1991 (hereinafter "the Odometer Act"), and Department of Transportation Regulations, 49 C.F.R. Sections 580.1-.7, as well as pendent state claims based on the identical illegal conduct giving rise to the action under the Odometer Act. Plaintiffs allege that Defendant the Car Lot, Inc., a New Mexico

corporation owned and operated by Defendants Douglas Ray Burns, Sr., and his wife, Defendant Sally Burns, engaged in the routine, regular, and intentional practice of selling used automobiles whose odometers were fraudulently and illegally altered and "rolled back" in violation of federal and state law. As shown by the criminal case report prepared by the Alamogordo Department of Public Safety which is attached to the First Amended Complaint as Exhibit B [not reprinted infra], Mr. and Mrs. Burns have freely admitted their involvement and guilt in this pervasive criminal scheme.1 The named Plaintiffs in this case and the class which they represent are persons who purchased from the Car Lot, Inc. used automobiles with rolled back odometers and who financed those purchases by executing retail installment contracts which were assigned to the Defendant First National Bank in Alamogordo (Bank). As the holder of the retail installment contracts employed to finance these fraudulent transactions, the Bank is liable for all claims which the Plaintiffs and the class which they represent could assert against the Car Lot, Inc. The limited factual predicate necessary to resolve this legal issue is not in dispute and, particularly in this case, resolution of this question of liability will serve the purpose of Rule 56 and the interests of all concern to narrow the issues which remain outstanding. Accordingly, Plaintiffs seek hereby partial summary judgment so declaring that liability. II. STATEMENT OF UNCONTROVERTED FACTS

I Mr. and Mrs. Burns refuse to admit or deny the operative allegations in the First Amended Complaint concerning their culpability and liability in this scheme but instead purport to invoke their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination to so respond. Answers filed by the Burnses, paragraph 7. While the Burnses of course enjoy a constitutional right not to so incriminate themselves, National Acceptance Company of America v. Bathalter, 705 F.2d 924 (7th Cir. 1983), their invocation of that right to refuse to address matters relevant to this civil litigation carries with it dire evidentiary consequences. Baxter v. Palmigiano, 425 U.S. 308 (1976), and Lefkowitz v. Cunningham, 431 U.S. 801 (1977). As the instant Motion does not address the ultimate wrongdoing underlying this case, these and other matters will be discussed in the comprehensive summary judgment motion which Plaintiffs anticipate will be filed at the conclusion of the discovery period.

1. The Car Lot, Inc. entered into 114 transactions selling used motor vehicles, each of which transactions were financed through a retail installment contract which was assigned to the Bank. (Responses to Plaintiffs' First Request for Production.) 2. Each of the 114 retail installment contracts is printed on the identical form, with the assignment to the Bank pre-printed, and each is identical to the retail installment contracts executed by the named Plaintiffs herein and attached to and incorporated in the First Amended Complaint. (First Amended Complaint, Paragraph 18, and Bank's Answer thereto, and Responses to Plaintiffs' First Requests for Production.) 3. Each of the 114 retail installment contracts contains the following clause in bold print and capital letters immediately above the signature lines: NOTICE: ANY HOLDER OF THIS CONSUMER CREDIT CONTRACT IS SUBJECT TO ALL CLAIMS AND DEFENSES WHICH THE DEBTOR COULD ASSERT AGAINST THE SELLER OF GOODS OR SERVICES OBTAINED PURSUANT HERETO OR WITH THE PROCEEDS HEREOF. RECOVERY HEREUNDER BY THE DEBTOR SHALL NOT EXCEED AMOUNTS PAID BY THE DEBTOR HEREUNDER. (First Amended Complaint, paragraphs 11 and 18, and the Bank's Answers thereto.) III. ARGUMENT OF LAW A. The Bank is liable as a holder, and not a holder in due course, of the installment contracts In accordance with the well established rules recited in the Uniform Commercial Code, a holder not enjoying the status of a holder in due course is subject to all claims which any person may assert in connection with the assigned contract. Section 55-3-306 N.M.S.A. 1978; See Schmitz v. Smentouwski, __ N.M. __, State Bar Bul. Vol. 29, No. 6, p. 131 at 134 (1990). The burden of establishing a party's status as a holder in due course is placed firmly on the party asserting that status. Section 55-3-307(3) N.M.S.A. 1978; Gebby v. Carrillo, 25 N.M. 120, 177 P. 894 (1918). Thus, unless the Bank can meet its burden to establish holder in due course status, Plaintiffs are entitled to entry of partial summary judgment declaring that the Bank is liable for the illegalities perpetrated by its assignor.

In fact, the Bank is not entitled to and does not claim holder in due course status and has not pled any such status as an affirmative defense in its Answer. A party must plead as an affirmative defense under Rule 8(c), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, any of the enumerated defenses or "any other matter constituting an avoidance or affirmative defense." The prevailing rule in the federal courts is that state law allocating burdens of proof determines whether a particular matter must be affirmatively pled as a defense. Freeman v. Chevron Oil Company, 517 F.2d 201, 204 (5th Cir. 1975). The specific defense here has routinely been held to be an affirmative one. National Resources, Inc. v. Wineberg, 349 F.2d 685, 688, n. 3 (9th Cir. 1965), cert. denied, 382 U.S. 1010 (1966), and United States v. Demmar, 76 F. Supp. 336, 338 (D. Mont. 1947), and cases cited therein. Since the Uniform Commercial Code clearly allocates the burden of proof to maintain such a defense on the person so asserting it, Section 55-3-307(3) N.M.S.A. 1978, as discussed above, if the Bank wished to assert this status, it needed to so plead in its Answer. Having failed to do so, it has waived such a claim. Radio Corporation of America v. Radio Station KYFM, Inc., 424 F.2d 14, 17 (10th Cir. 1970), and Kaye v. Smitherman, 225 F.2d 583 (10th Cir.), cert. denied, 350 U.S. 913 (1955). Even assuming that the Bank had not waived any defense which might otherwise be available as a holder in due course, the hallmark of a holder in due course is one who is the holder of a negotiable instrument, as defined by Section 55-3-104 N.M.S.A. 1978. However, a negotiable instrument must "contain an unconditional promise or order to pay a sum certain in money and no other promise, order, obligation or power given by the maker or drawer except as authorized by this article..." Section 55-3-101(l)(b). The retail installment contracts assigned to the Bank here do not meet this requirement as the document contains a virtually endless list of other agreements and conditions burdening the obligation to pay. A clear statement and explanation of this rule is stated in Geiger Finance Company v. Graham, 182 SE.2d 521, 123 Ga. App. 771 (1971). The Geiger Finance Company opinion deals with the identical issues presented here -- whether the holder of a typical and unremarkable retail installment contract executed by a consumer purchaser may be considered a holder in due course.

The court there reviewed the various contract terms, virtually all of which and several others are present here, and concluded that the waiver provisions, insurance provisions, future advances clause, and security agreement all defeat holder in due course status: If a writing contains any other promise, order, obligation or power, it is simply not a negotiable instrument and the concept of a holder in due course does not apply. 182 SE.2d at 524.

The same result is inescapable here.

B. The Bank has subjected itself to liability by the terms of the contract.

As recited in Section II(3) above, each of the 114 retail installment contracts potentially at issue here contains the identical "NOTICE" stating that the holder of the contract "is subject to all claims and defenses which the debtor could assert against the seller of goods or services obtained pursuant hereto...." This contractual language is the verbatim notice which all such consumer credit contracts must contain in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission Regulation entitled "Preservation of Consumers' Claims and Defenses," 16 C.F.R. Part 433.1 et seq. The purpose of this Federal Trade Commission Regulation is to achieve precisely the result which attains here: consumers who have been victimized by an unscrupulous seller should not be placed in the position to bear the resulting losses instead of the bank or other financing entity which regularly has dealt with the seller and which has profited from the transaction. See Statement of Basis and Purpose, 40 F.R. 53524 (Nov. 18, 1975). Here, the seller, the Car Lot, Inc., is now defunct (See Answer of Douglas Ray Burns, Sr., paragraph 3), and any recovery from the actual perpetrators of the odometer tampering scheme at issue here seems remote. As many

other affirmative statements of positive law, this Federal Trade Commission Regulation allocates risks of loss as an expression of national public policy. Federal and state courts have been vigilante in enforcing this standard contractual provision. In Cox v. First National Bank of Cincinnati, 633 F. Supp. 236 (S.D. Ohio 1986), the federal court imposed liability under the Truth In Lending Act [15 U.S.C. Sections 1601 et seq.] on the defendant bank which was the holder of a consumer credit contract containing the required notice. Despite the fact that the Truth In Lending Act itself, 15 U.S.C. Section 1614, expressly limits the liability of assignees to violations which are "apparent on the face" of the disclosure document, the federal district court in Cox nevertheless found the bank liable for a non-facial violation on the basis of the contract provision mandated by the Federal Trade Commission. 635 F. Supp. at 239. In Jefferson Bank & Trust Company v. Stamatiou, 384 So.2d 388 (La. 1980), the Supreme Court of Louisiana gave full effect to the mandated provision and held that the bank which was the holder of a promissory note was indeed subject to "all claims and defenses" although the instrument was generated in a commercial transaction not subject to the Federal Trade Commission Regulation. In Stamatiou, the parties had unnecessarily used a form note designed for consumer transactions subject to the Regulation. The bank asserted that as a result the contract provision should not be enforced. The Supreme Court of Louisiana rejected that argument and concluded that, regardless of the reason that the provision was included, the language is an explicit provision of the contract and must be enforced as written. Accord, In re Gray, 49 B.R. 540, 543-544 (Bkrtcy E.D.Va. 1985), and Boden v. Atlantic Federal Savings and Loan Association, 396 S.2d 827 (Fla. App. 1981). The absence of any evidence that the Bank participated in the wrongdoing is of no consequence. Indeed, it is the reason why liability of the Bank is established. As observed by the Texas Supreme Court under similar circumstances, the purpose of the required Notice is to eliminate the doctrine of holder in due course in consumer credit transactions, a status which

under the Uniform Commercial Code is predicated on good faith and lack of knowledge of adverse claims [See Section 55-3-302(l)(b) and (c)]: In abrogating the holder in due course rule in consumer credit transactions, the FTC preserved the consumer's claims and defenses against the creditor-assignee. The FTC rule was therefore designed to reallocate the cost of seller misconduct to the creditor. The commission felt the creditor was in a better position to absorb the loss or recover the cost from the guilty party -- the seller.

Home Savings Association v. Guerra, 733 S.W.2d 134, 135 (Tex. 1987). It is this public policy which Plaintiffs now move this Court to enforce. IV. CONCLUSION Whether viewed as a holder not in due course or a party to a contract which explicitly subjects its holder to all claims and defenses which could be asserted against the underlying seller, the Bank is liable for the violations of state and federal law committed by the Car Lot, Inc. Accordingly, Plaintiffs are entitled to partial summary judgment so declaring that liability.

Respectfully submitted,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

3.9

Plaintiff's Reply Memorandum In Support Of Motion For Partial Summary Judgment

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO

JOHNSON, VEGA, RODRIGUEZ, NORRELL, NORRELL, DURAN, and SEILER Individually and on behalf of all other persons

similarly situated, Plaintiffs, [vs.] FIRST NATIONAL BANK IN ALAMOGORDO, THE CAR LOT, INC., a New Mexico Corporation, DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Sr., DOUGLAS RAY BURNS, Jr., and SALLY BURNS, Defendants. No. CIV 89-1137 HB

PLAINTIFFS' REPLY MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT

I. INTRODUCTION

Defendant First National Bank in Alamogordo (the "Bank") has filed its responsive Memorandum in opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion For Partial Summary Judgment. The most significant aspects of this responsive brief are its omissions and the matters which the Bank appears to concede. The Bank has not disputed the statement of uncontroverted facts recited by Plaintiffs, thus admitting the truth of each such matter [Local Rule 56.1(b)] and affirming that the issue presented is ripe for partial summary judgement. The Bank further has failed to address the primary argument advanced by Plaintiffs establishing its liability -- that under New Mexico law, the Bank, as a holder rather than a holder in due course of the subject installment contracts, is liable for the acts and omissions of its assignor. Finally, the Bank appears to concede that it is liable for the actual damages suffered by the Plaintiffs and objects only to liability for treble and punitive damages.

II. ARGUMENT OF LAW A. The Bank is liable as a holder, and not a holder in due course, of the installment contracts. The Bank has responded to Plaintiffs' Motion For Partial Summary Judgment by ignoring the primary basis on which Plaintiffs have asserted its liability, that is, that the Bank is a holder, and not a holder in due course, of the installment contracts. Without any discussion whatsoever of Plaintiffs' primary argument, the Bank simply skips over this contention and states as follows as its initial summary of its Memorandum: Plaintiffs rely on this language of the FTC rule for their affirmative claims against the Bank for punitive and treble damages pursuant to 15 U.S.C. Section 1981 et seq. (Memorandum, p. 2).

Plaintiffs have clearly and explicitly explained that the Bank's liability is established based on either the inclusion of the mandated FTC notice in the installment contracts or its status as a holder, rather than a holder in due course, of the installment contracts. The Bank's refusal and failure to address this primary basis of liability can only be deemed to be its consent to Plaintiffs' contention. This conclusion is mandated by both the requirements of Local Rule 56.1(b), which requires a party opposing summary judgement to "file a written memorandum containing a short, concise statement of the reasons in opposition to the motion with authorities," as well as by the practical consideration that its silence leaves the contention uncontroverted. Whether or not the Bank intended to consent to partial summary judgement on this point, it has no argument in opposition. The Bank is admittedly a holder and not a holder in due course of the installment contracts and under the Uniform Commercial code is therefore "subject to (a) all valid claims to it on the part of any person . . . . Section 55-3-306 N.M.S.A. 1978. Plaintiffs concede that they are not entitled to recover, either affirmatively or by set-off, any amounts in excess of the face amounts of the installment contracts. Such an excess recovery here, where the

Bank's liability flows only from the fraudulent acts of its assignor, is not permitted under this provision of the Uniform Commercial Code or any other theory of derivative liability. On the other hand, Section 55-3-306 unambiguously subjects the Bank to liability for "all valid claims" in addition to "all defenses." Compare Section 55-3-306(a) with subsections (b), (c), and (d). Official Comment 2 to this provision leaves no doubt that subsection (a) authorizes Plaintiffs to recover all sums from the transactions without limitation as to the nature of the claims: "All valid claims to it on the part of any person" includes not only claims of legal title, but all liens, equities, or other claims of right against the instrument or its proceeds. It includes claims to rescind a prior negotiation and to recover the instrument or its proceeds. (Emphasis added).

The recent decision of the New Mexico Supreme Court in Schmitz v. Smentovski, __ N.M. __, 785 P.2d 726 (1990), clearly illustrates and confirms this point. In Schmitz, the defendant bank sought to overturn a jury award of compensatory and punitive damages on the basis that it was a holder in due course of the subject note. The New Mexico Supreme Court sustained the jury's determination that the bank was not a holder in due course on the facts presented. Having failed to sustain its burden of proving its privileged status, the judgment against the bank was affirmed in full. The New Mexico Supreme Court applied Section 55-3-306 as written, subjecting the holder to all claims and finding no bar to the award of either compensatory or punitive damages.

B. The Bank has subjected itself to liability by the terms of the contract.

In view of the Bank's liability as a mere holder of the installment contracts and of the Bank's failure to dispute this claim, this Court need not reach the issue of its liability under the

Federal Trade Commission Rule. Nevertheless, as this is the only contention addressed by the Bank, Plaintiffs accordingly must reply. The Bank's position regarding the Federal Trade Commission Rule appears to be the following: "An account debtor may sue the creditor under the FTC rule to discontinue credit payments." (Memorandum p.2). On the other hand, the Bank appears to take a contrary position, recognizing that any recovery is permitted within the conceded limitation of the amount of the installment contract: "Each automobile purchaser damaged by the Car Lot, Inc.'s wrongful acts may be entitled to his actual damages as set-off against the Bank, but not in amounts that exceed the amount paid." (Memorandum p. 3). The only clear statement on this issue by the Bank is its objection to imposition of unlimited liability, a position with which Plaintiffs fully concur. The Federal Trade Commission Rule authorizes a consumer to recover in affirmative litigation from an assignee such sums as may be owing by the assignor for any and all claims so long as the recovery does "not exceed amounts paid by the debtor" under the contract. This unremarkable proposition is the precise holding by the Texas Supreme Court in Home Savings Association v. Guerra, 733 SW2d 134 (Tex. 1987). In Guerra, the intermediate appellate court had affirmed a judgment against an assignee in the amount of $25,000 and the voiding of a note in the amount of $7,700, on which the consumer had paid $1,256.90. The Texas Supreme Court reversed the decision in part, holding that the assignee's derivative liability could not exceed the contract amount, that is, the $1,256.90 paid and the voiding of all other payments due on the note. Guerra was an affirmative suit filed by the consumer, as here, against the assignor wrongdoer and the bank/assignee. Although the underlying claims are different, the holding in Guerra states the rule which Plaintiffs are urging this Court to adopt. Squarely on point and directly in opposition to the Bank's unsupported contention is the decision in Thomas v. Ford Motor Credit Company, 429 A.2d 277 (Md. App. 1981). In Thomas, the Plaintiff such an automobile seller and the finance company which was the holder of the purchase money contract containing the required Federal Trade Commission Notice. The appellate court held that the complaint adequately stated a claim against the assigned finance

company for compensatory and punitive damages based solely on its derivative liability and rejected the contention that the assignee could not be sued affirmatively by the customer to recover the contract amount. The only limitation placed by the Thomas court on the customer's claims or the assignee's derivative liability was that the recovery may not exceed the contract sum. Similarly in Boden v. Atlantic Federal Savings and Loan Association, 396 S.2d 827 (Fla. App. 1981), the court reversed a trial court's denial of relief to consumers who purchased a swimming pool which failed to conform to depth specifications and who sued the assignee savings and loan to avoid all future payments and recover all sums already paid. The court applied the FTC rule as written, reversing the trial court's decision and holding the assignee to the terms of the notice. The Bank cites several cases re-stating the statutory standard that liability under the Odometer Act is limited to acts taken "with intent to defraud." Plaintiffs will of course prove that the Bank's co-Defendants rolled back the odometers with such an intent. However, none of the cases cited by the Bank supports its contention regarding the derivative liability now sought to bc established. In fact, one case so cited, Parker v. DeKalb Chrysler Plymouth, 459 F. Supp. 184 (N.D. Ga. 1978), aff'd. 673 F.2d 1178 (11th Cir. 1982), only serves to support Plaintiffs' position. In Parker, the plaintiff sued both an automobile dealer and the assignee bank for direct violations of the Odometer Act as well as for disclosure violations under the Truth In Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. Sections 1601 et seq. The court dismissed the claim under the Odometer Act as to the bank for the plaintiff's failure to allege or prove that it acted with the requisite fraudulent intent. The case does not address at all the derivative liability now under consideration, and to that extent fails to serve the Bank's position. However, the Parker court did observe that a comparison "of the Truth in Lending Act and the Odometer Act reveals a similarity of purpose and design . . . ," including their "private attorneys-general" enforcement mechanism with mandatory civil penalties. 459 F. Supp. at 186-187. The significance of this observation in Parker is that in Cox v. First National Baizk of Cincinnati, 633 F.Supp. 236, 239 (S.D. Ohio 1986), the federal district

court applied the derivative liability mandate of the Federal Trade Commission Rule in the context of imposing liability on a bank for its assignor's violation of the Truth-in-Lending Act. The only relevance of the Parker decision is by its stated analogy to show that derivative liability of the Bank is similarly established. The Bank's claim, unsupported by any authority whatsoever, that Plaintiffs may not assert an affirmative claim under the Federal Trade Commission rule but may only raise the violations of the Odometer Act defensively as a set-off if sued is refuted by the same case on which it relies to avoid liability generally. In Ford Motor Credit Company v. Morgan, 536 NE2d 587 (Mass. 1989), the court explicitly rejected such a position: We do not hold that a consumer may only assert his rights defensively in response to a claim initiated by an assignee for balance due on the contract. This would be in clear contravention of the FTC's intention. 536 NE2d at 590, n. 5. Accord, Thomas v. Ford Motor Credit Company, supra, 429 A.2d at 282, and Vasquez v. Superior Court of San Joaquin County, 484 P.2d 964, 979-980, 94 Cal. Rptr. 796, 823-824 (1971).

The Bank cites Morgan for the proposition that an affirmative suit against an assignee for derivative liability under the Federal Trade Commission rule is available only to remedy a "substantial" violation by the assignor. Plaintiffs' response to this proposition is two-fold: first, the assignor's conduct here of engaging in willful criminal behavior in violation of both federal and state law, affirmatively misstating the condition of high mileage used cars and extracting additional profit from each Plaintiff by charging a cash price as though the vehicles were low mileage, is precisely the type of predatory business practice which meets any standard of substantiality; and second, the decision in Morgan is in any event a misapplication of the Federal Trade Commission Rule. The Morgan court based its decision on a single sentence in the Federal Trade Commission comment accompanying promulgation of the Rule. That comment is unsupported