Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Major mistake: Comprehending the whole hypo

Uploaded by

Gautam AroraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Major mistake: Comprehending the whole hypo

Uploaded by

Gautam AroraCopyright:

Available Formats

9/15/2011 8:14:00 PM Major mistake 1: The attempt to comprehend the whole.

Never think about a hypo or a problem from a substantial standpoint of what is gong on here legally? Preliminary overview: 2 phases Phase 1: Immediately read any instructions and flip through the exam to gather an over all sense of the format. 30-45 seconds! Phase 2: read the question at the end The only way to consistently achieve a concise, orderly, relevant discussion is to have perspective before you write, to follow a plan. to 1/3 of the time should be allotted to the planning phase if longer hypo i.e. 90 minutes, break planning down into two 10ish minute chunks stick to these limits. It forces you to hustle and get something down on paper plan, write, plan write, in intermittent, energetic segments until time is called Planning phase: Step 1 Identify all conflicting pairings relevant to the questions/instructions at the close of the hypothetical, and the objective(s) of each party to the pairing. Remember, goal of law is conflict resolution so there are bound to be conflicts in hypos Objectives DOES NOT mean legal objectives, but real world objectives i.e. money, jailtime, making P whole again. Analysis must be practical, two sided and goal oriented The examinee who adopts an aggressive, exploitative attitude and approach is much more likely to mull over the facts and pull out subtle points meriting discussion. Person will exhaust the hypos possibilities] Step 2 Identify all the premises Identify counter premises (i.e. exceptions to the rule) Premise = legal basis Break it down into chunks and read selectively. Phrase here, sentence there.

Step 2 doesnt call for an analysis of whether a premise can succeed. Merely identify it as colorable. NEW (RELEVANT) LAW, NEW (RELEVANT) THINKING Dont exclude analysis of something because you think its too obvious and that the professor doesnt want to see it. Likely, he does. o Question is not whether or not to show it but how much time to expend on it (major v. minor issues) For every premise raised, consider the colorable response that could be make by other side.

Be objective, and consider the issue from both standpoints o Any sort of emotional involvement with facts hampers objectivity. Do not reach a conclusion before your analysis o Treat is like a tennis/ping pong back and forth battle Stepts 1+2+preliminary overview = THE BLENDER. This is all you need for initial issue spotting. Elements/subelements/subsubelements create premises which are to be analyzed in paragraphs. Most of the issues arise of such elements You must learn to think about elements, not overall premises, in order to pinpoint what specifically needs to be discussed in order to resolve the issue A common sense view of things is the most important ingredient in fashioning a lawyerlike analysis. Quickly identify the real issue o To ID a non-issue, ask are any of the parties contesting this? if not, its likely a non-issue. Step 3: preview as best as you can which premises constitute major issues, and which ones a minor. Preview whether one element is so obviously lacking as to immediately dispose of the premise. Second, whether any real issues are raised by the premise. If you cant find any conflict in elements, you are probably not looking closely enough Where contest over elements is close (real issue), display the most creative, insightful, logical arguments that the opposing party

can make within the confines of given reasonably inferable facts. This is where policy discussion may come in handy All you want at this stage is a sense that an elements is lacking, or that competing arguments exist Introducing the premise (issue) Just launch into a paragraph, beginning with a statement of the law that is relevant to the premise. The issue is thereby implied. NEW LAW, NEW PARAGRAPH. Avoids needless wordy introductions and transitions. ABRUPTLY BEGIN EACH PARAGRAPH WITH A NEW LAW. No filler, time consuming transitions necessary. Cover counter-premises/counter-issues, even though the question does not explicitly state it. Teacher probably wants to see this analysis. Analysis step: you can go premise/counter premise for each and every element. OR you can do premise premise premise premise followed by counter counter counter. Just make sure the reader can follow you. You simply continue the discussion by matching numbers with evidence/arguments for and against the establishment of the number represented by the element In a case where one of the elements is clearly missing (not a real issue), still law out all of the elements of the law in case your reader might presume that you dont know the law. Play it safe. Express only what needs to be said on the exam concisely. Get good at the game. Become focused on analysisthe thinking process. Fascination with the game of making arguments, with exploring all possibilities as an end in itself will likely result in arguments and insights, surprises (including issues the professor may have overlooked, but should have noted) that impress the grader and earn the A Dont commit strongly in your conclusion. Use phrases like probably, on balance o Also, mention the main points that the conclusion relies on (the real issues), which further distracts the grader from the

UBE

conclusion towards the analysis. Hedge these as well (inter alia) Arguments are factually based. They marshall and interpret evidence, facts. They occur in the context of establishing a premise. Premises and counterpremises are legal concepts, each sufficient in itself (a complete legal theory of entitlement) o Imagine each party and client in a hypo is real. Gives you a sense of urgency to solve their issues because something of value is at stake. It forces you to dig deeper. o A policy argument is nothing but another tool. A policy argument is just another premise! o

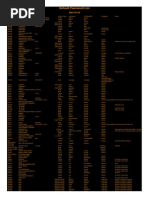

You might also like

- Day of The Law ExamDocument3 pagesDay of The Law ExamProfesssor John DelaneyNo ratings yet

- LEEWS Final NotesDocument1 pageLEEWS Final NotesHollyBriannaNo ratings yet

- Getting To Maybe OutlineDocument3 pagesGetting To Maybe OutlineAlexSmith100% (2)

- FAQ Preparing For The Law School ExamsDocument10 pagesFAQ Preparing For The Law School ExamsProfesssor John Delaney100% (1)

- Torts OutlineDocument62 pagesTorts OutlineZach100% (2)

- Contracts 1 - Quick Issue Spotting GuideDocument8 pagesContracts 1 - Quick Issue Spotting GuideVirginia Crowson100% (1)

- Contract Essentials in Under 40Document22 pagesContract Essentials in Under 40realtor.ashley100% (1)

- Kucc FlowchartDocument1 pageKucc Flowchartsuperxl2009No ratings yet

- Torts Attack OutlineDocument1 pageTorts Attack Outlinebrittany_bisson_2No ratings yet

- Criminal Law Godsoe Brooklyn Law OutlineDocument22 pagesCriminal Law Godsoe Brooklyn Law OutlineJames BondNo ratings yet

- Outline For EssayDocument62 pagesOutline For EssayJames Andrews100% (1)

- Civ Pro Rule Statements DraftDocument3 pagesCiv Pro Rule Statements DraftkoreanmanNo ratings yet

- Law Exam Tips for Spotting IssuesDocument11 pagesLaw Exam Tips for Spotting Issuesryananderson14No ratings yet

- How To Write A Civil Procedure ExamDocument2 pagesHow To Write A Civil Procedure Examdpi247100% (1)

- Contract Law Objective TheoryDocument122 pagesContract Law Objective Theoryoaijf100% (1)

- Crim Attack Outline GKDocument8 pagesCrim Attack Outline GKLiliane KimNo ratings yet

- Contracts OutlineDocument18 pagesContracts OutlineSam Levine100% (2)

- Prewrite PacketDocument15 pagesPrewrite PacketBlairNo ratings yet

- Formation, acceptance, consideration in contract lawDocument19 pagesFormation, acceptance, consideration in contract lawDavid Jules BakalNo ratings yet

- Contracts Outline - WpsDocument55 pagesContracts Outline - WpsrockisagoodNo ratings yet

- Ucc and Restatement OutlineDocument7 pagesUcc and Restatement OutlineLauren WoodsonNo ratings yet

- Bartlett - Contracts Attack OutlineDocument4 pagesBartlett - Contracts Attack OutlinefgsdfNo ratings yet

- Torts Attack OutlineDocument10 pagesTorts Attack OutlineElla Devine100% (1)

- Contracts Outline, Bender, 2012-13Document70 pagesContracts Outline, Bender, 2012-13Laura CNo ratings yet

- Essay Format Strict Product Liability (MFG)Document2 pagesEssay Format Strict Product Liability (MFG)Harley Meyer100% (1)

- Law School - Contracts NotesDocument17 pagesLaw School - Contracts NotesKJ100% (2)

- Crim Exam OutlineDocument29 pagesCrim Exam OutlineSunny Reid WarrenNo ratings yet

- Contracts 1 - OutlineDocument17 pagesContracts 1 - OutlineMarlene MartinNo ratings yet

- 1L - Criminal - OUTLINEDocument18 pages1L - Criminal - OUTLINEtanner boydNo ratings yet

- Tort Law Outline - 1L Fall 2012Document38 pagesTort Law Outline - 1L Fall 2012JFSmith231No ratings yet

- 1L Contracts Exam Outline Checklist Attack SheetDocument2 pages1L Contracts Exam Outline Checklist Attack SheetSara Zamani67% (3)

- Torts Battery Essay OutlineDocument5 pagesTorts Battery Essay OutlineKMNo ratings yet

- Con Law II Vandevelede Outline (Ross)Document43 pagesCon Law II Vandevelede Outline (Ross)chrisngoxNo ratings yet

- TORTS EXAM TITLEDocument5 pagesTORTS EXAM TITLEjennwyse8208No ratings yet

- Contracts Final OutlineDocument19 pagesContracts Final OutlineCatherine Merrill100% (1)

- Contracts Just The Rules PDFDocument28 pagesContracts Just The Rules PDFcorry100% (1)

- How To Write A Negligence Answer For Torts ExamDocument4 pagesHow To Write A Negligence Answer For Torts ExamPhillip Gordon MulesNo ratings yet

- Contracts OutlineDocument48 pagesContracts Outlinekino321100% (2)

- CONTRACTS II: PAROL EVIDENCE RULEDocument37 pagesCONTRACTS II: PAROL EVIDENCE RULEBrandon YeboahNo ratings yet

- Tiff's Crim Law OutlineDocument37 pagesTiff's Crim Law Outlineuncarolinablu21No ratings yet

- Getting To Maybe OutlineDocument5 pagesGetting To Maybe Outlinemichelleovanes100% (2)

- Civil Procedure OutlineDocument53 pagesCivil Procedure OutlineCory BakerNo ratings yet

- Contracts II OutlineDocument16 pagesContracts II OutlineEva CrawfordNo ratings yet

- Commerce Clause Cases ExplainedDocument1 pageCommerce Clause Cases ExplainedkillerokapiNo ratings yet

- Attack OutlineDocument3 pagesAttack OutlineSam Rodgers100% (2)

- Products Liability 3Document46 pagesProducts Liability 3phil_edelsonNo ratings yet

- Contracts Outline II Professor Knapp I. Parol Evidence Under The UCCDocument43 pagesContracts Outline II Professor Knapp I. Parol Evidence Under The UCCieaeaea100% (1)

- Exam Outline Civ ProDocument24 pagesExam Outline Civ ProPuruda Amit100% (1)

- Glannon Guide To TortsDocument7 pagesGlannon Guide To TortsSportzFSUNo ratings yet

- Leg Reg Pre WriteDocument19 pagesLeg Reg Pre WriteashleyamandaNo ratings yet

- Erie DoctrineDocument14 pagesErie DoctrineLisa B LisaNo ratings yet

- MPC Accomplice Liability and Common Law Conspiracy ComparedDocument12 pagesMPC Accomplice Liability and Common Law Conspiracy ComparedRick Coyle100% (1)

- Civ Pro Attack OutlineDocument3 pagesCiv Pro Attack OutlineDeeNo ratings yet

- MPRE KramerDocument44 pagesMPRE KramerVic Eke100% (6)

- Ethics Chart v1Document22 pagesEthics Chart v1doesntmatter555100% (1)

- Professional Responsibility OUtlineDocument6 pagesProfessional Responsibility OUtlinelaura_armstrong_1067% (3)

- Civ Pro Personal Jurisdiction Essay A+ OutlineDocument5 pagesCiv Pro Personal Jurisdiction Essay A+ OutlineBianca Dacres100% (1)

- Writing LessonDocument3 pagesWriting Lessonapi-351448195No ratings yet

- PUMBA Time Table for MBA SubjectsDocument7 pagesPUMBA Time Table for MBA SubjectsSanket PondeNo ratings yet

- English 9: First Quarter: Week 2 ConditionalsDocument7 pagesEnglish 9: First Quarter: Week 2 ConditionalsDaniel Robert BuccatNo ratings yet

- Pages From A Search For Two QuartersDocument17 pagesPages From A Search For Two QuartersPageMasterPublishingNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Entrepreneurial Finance 4th Edition Leach Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Entrepreneurial Finance 4th Edition Leach Test Bank PDF Full ChapterRandyLittlekcrg100% (5)

- Az - History Book Year 8Document60 pagesAz - History Book Year 8Nargiz AhmedovaNo ratings yet

- Daily Activity: Grade 5 Lefi Adiba MangawingDocument30 pagesDaily Activity: Grade 5 Lefi Adiba MangawingLefi AdibaNo ratings yet

- Glorious Grace Day 9: Take Time To Listen - JosephPrince - Com BlogDocument3 pagesGlorious Grace Day 9: Take Time To Listen - JosephPrince - Com Blogadebee007No ratings yet

- HCC Container DesignDocument6 pagesHCC Container Designlwct37No ratings yet

- 6231A ENU CompanionDocument181 pages6231A ENU CompanionGiovany BUstamanteNo ratings yet

- Coding Competition SolutionDocument6 pagesCoding Competition Solutionsubhasis mitraNo ratings yet

- Certificate For Committee InvolvementDocument1 pageCertificate For Committee InvolvementKemberly Semaña PentonNo ratings yet

- Mohanty Consciousness and KnowledgeDocument9 pagesMohanty Consciousness and KnowledgeRobert HaneveldNo ratings yet

- K-Book Trends Vol 55Document99 pagesK-Book Trends Vol 55higashikuniNo ratings yet

- Bakhurst, Shanker - 2001 - Jerome Bruner Culture Language and SelfDocument349 pagesBakhurst, Shanker - 2001 - Jerome Bruner Culture Language and SelfAlejandro León100% (1)

- Orange Song LyricsDocument7 pagesOrange Song Lyricsshaik jilanNo ratings yet

- Activity IIDocument11 pagesActivity IITomás SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Practice Court ScriptDocument13 pagesPractice Court ScriptJANN100% (1)

- Story Map Rubric AssessmentDocument2 pagesStory Map Rubric AssessmentGem Baque100% (2)

- Comp 122 Comp121 Cosf 122 Discrete StructuresDocument5 pagesComp 122 Comp121 Cosf 122 Discrete Structuresvictor kimutaiNo ratings yet

- 14th ROMAN 4.2Document7 pages14th ROMAN 4.2Dhruv BajajNo ratings yet

- WebMethods Introduction To Integration EAI and B2BDocument6 pagesWebMethods Introduction To Integration EAI and B2BRolexNo ratings yet

- Cheng and Fox (2017) - Beliefs About AssessmentDocument13 pagesCheng and Fox (2017) - Beliefs About AssessmentSamuel SantosNo ratings yet

- Lesson 01 - Introduction To Noahide LawsDocument9 pagesLesson 01 - Introduction To Noahide LawsMilan KokowiczNo ratings yet

- Exercício Have GotDocument2 pagesExercício Have Gotdeboramonteiro14No ratings yet

- Resume Tata Consultancy ServicesDocument14 pagesResume Tata Consultancy ServicesSanjayNo ratings yet

- Content Collector 3 Install GuideDocument772 pagesContent Collector 3 Install GuideLambert LeonardNo ratings yet

- Phenoelit Org Default Password List 2007-07-03Document14 pagesPhenoelit Org Default Password List 2007-07-03林靖100% (1)

- Embedded System Design Using Arduino 18ECO108J: Unit IvDocument53 pagesEmbedded System Design Using Arduino 18ECO108J: Unit IvHow MeanNo ratings yet

- Short Answer Questions: 1. Write The Structure of PHP Script With An ExampleDocument26 pagesShort Answer Questions: 1. Write The Structure of PHP Script With An ExampleMeeraj MedipalliNo ratings yet