Professional Documents

Culture Documents

H P Ray

Uploaded by

Abhimanyu KumarOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

H P Ray

Uploaded by

Abhimanyu KumarCopyright:

Available Formats

The apsidal shrine in early Hinduism: origins, cultic afliation, patronage

Himanshu Prabha Ray

Abstract

This paper argues against the current view that the apsidal form was Buddhist in origin and that apsidal Hindu temples are essentially Buddhist shrines subsequently converted to Hinduism. It also counters the linear view of religious change, which suggests that the Hindu temple came into its own after the decline of Buddhism in the fourthfth centuries AD. Instead, the paper establishes that the apsidal form was part of a common architectural vocabulary widely used from the second century BC onwards not only for the Buddhist shrine, but also for the Hindu temple and several local and regional cults. The historical development of the apsidal shrine is traced at three levels. One is at the macro-level of the Indian subcontinent from the second century BC to the nineteenth century AD. Second is the location of the apsidal form in the religious landscape of a particular site, viz. that of Nagarjunakonda in the lower Krishna valley in Andhra. Finally, the paper highlights the archaeological excavations conducted at the apsidal temple of Gudimallam also in Andhra to trace the history of the religious site from the second century BC to the twelfth century AD, the objective being to highlight the changing nature of the Hindu temple. The paper thus makes a case for plurality of religious beliefs and practices in ancient South Asia as against the prevailing view that these local and regional cults were gradually subsumed under the mantle of Sanskritization starting from the fourthfth centuries onwards.

Keywords

Hinduism; Buddhism; Nagarjunakonda; Gudimallam; Sanskritization.

Introduction Here, briey and in accordance with the treatises, I present one storied temples. . ..Their plan may be square, circular, rectangular or elliptical, apsidal, hexagonal or octagonal and the same plans are suitable for roofs. (Mayamatam, ch.19, 3b4a) This quotation from the Mayamatam, an architectural treatise compiled in south India from the early ninth to the late twelfth century AD clearly indicates that the apsidal plan is

World Archaeology Vol. 36(3): 343359 The Archaeology of Hinduism # 2004 Taylor & Francis Ltd ISSN 0043-8243 print/1470-1375 online DOI: 10.1080/0043824042000282786

344

Himanshu Prabha Ray

one of the many recommended forms of the Hindu temple (Dagens 1997: xliii). Yet in historical writing the current view suggests that the apsidal shrine was originally Buddhist and, where we see the apsidal form used in the Hindu temple, we are to interpret it as an originally Buddhist shrine converted into a Hindu temple. Thapar (2002: 314), for example, refers to apsidal shrines at Ter and Chezarla as Buddhist shrines converted into temples as a result either of gradual conversion or forced change. Sarkar (1993: 23) also reiterates this link between the apsidal structures and Buddhist religious practice in an otherwise comprehensive study of early architecture. When and how does this link between architectural form and a specic religious aliation take root in secondary writings? Relevant to this discussion is the rediscovery of religious architecture by colonial ocers of the Archaeological Survey of India, which was created in 1861 barely three years after British Raj had been established in India. Another change occurred in the post-Independence period with the shift in the 1950s in the writing of history. The emphasis moved from the writing of political history of India, where art and architecture was discussed in terms of the ruling dynasty, to socio-economic history, where religion came to be studied in relation to modes of production. It was a combination of both these trends that resulted in a somewhat unfounded link being created between architectural form and religious aliation and this paper argues against this prevailing view. This paper focuses on the apsidal shrine in an attempt to unravel three major strands: viz. the beginnings of temple architecture, the cultic aliation of early shrines and the nature of patronage that went into the making of early Hindu religious architecture from the secondrst centuries BC onwards. The shrine, as dened in this paper, is not merely a place of worship and a static indicator of royal generosity, but involved the active participation of the community for its establishment, maintenance and survival. Temples are ritual instruments and their function is to web individuals and communities into a complicated and inconsistent social fabric through time (Meister 2000: 24). It is the threads of this social fabric that need to be understood and appreciated. After preliminaries relating to the beginnings of temple architecture, I discuss the historical development of the apsidal shrine at three levels. One is at the macro-level, which traces the development of the apsidal form of the Hindu temple in the Indian subcontinent from the second century BC to the nineteenth century AD. Second is the location of the apsidal form in the religious landscape of a particular site, viz. that of Nagarjunakonda in the lower Krishna valley in Andhra, to emphasize the sharing of a common architectural vocabulary by several religious traditions, including those of the Buddhists and the Hindus. Finally, I highlight the archaeological excavations conducted at the apsidal temple of Gudimallam also in Andhra to trace the history of the religious site from the second century BC to the twelfth century AD, the objective being to concentrate on the changing nature of the Hindu temple.

Secondary writings on religious change Historians writing within the Marxist framework of Indian history associate Buddhism and Jainism with the growth of trade resulting from the development of an agrarian

The apsidal shrine in early Hinduism

345

surplus in the Ganga valley around the middle of the rst millennium BC. The expansion of trade networks and urban centres in the early centuries AD is seen as coinciding with a proliferation of Buddhist monastic centres. The subsequent decline of trade and decay of towns from AD 300 onwards is perceived as leading to the rise of feudal tendencies in Indian society (Sharma 1987). Buddhism is said to have weakened and the post-fourthcentury period is dened as marking a transitional phase between the sacricial Vedic religion and the emergence of Puranic worship marked by devotion to a deity, which was brought about by the migration of brahmanas from the towns and the development of tirthas or sacred pilgrimage spots (Nandi 1986). Brahmanas are credited with being agents of acculturation among the tribal populations from the fth century AD onwards. It is suggested that, at numerous feudal centres, temples were constructed in permanent material such as stone for the rst time in the fth century AD inspired by the growing importance of Bhakti and by the newly established Smarta-Pauranic religion, which was associated with the new social set-up (Desai 198990: 31; Nath 2001). Regional states emerged from the seventh to the tenth centuries marked by complex changes in religious dimensions of the society and it is believed that Bhakti and the worship through Bhakti of God as a Lord located in a temple, was the key ideological strand of the period (Chattopadhyaya 1994: 29). In contrast to this conventional linear development from Buddhist shrine to Hindu temple, recent research establishes that both the Buddhist shrine and the Hindu temple were contemporaneous in thirdrst centuries BC and shared sacred space with a diverse array of domestic, local and regional cults. It is also signicant that, rather than being subsumed through a process of acculturation within the dominant Brahmanical tradition as generally proposed, many of these local and regional cults continued to maintain autonomous religious traditions (Ray 2004: 35075). An appropriate example is the dedication of a shrine to the fertility cult of lajja-gauri (who is portrayed nude and giving birth in a squatting position) as evident from the site of Padri in the Talaja tahsil of Bhavnagar district of Gujarat hardly 2km from the Gulf of Cambay (Paul 2000: 5366). The site has Harappan beginnings, but was again occupied around the rst century BC. The only structure uncovered partially in the central part of the site was of stone construction; it had a roughly rectangular plan with rounded corners and a hardened oor of alternate layers of clay and gravel. Two terracotta plaques of lajja-gauri were found on the oor of the structure, while a square slate plaque with the image of lajja-gauri was a surface nd. Other images included sandstone gures of Ganesa and Vishnu (Shinde 1994: 4835). A fourth-century inscribed marble image of lajja-gauri found in 1940 on the north slope of Nagarjunakonda hill at the edge of a pillared hall of a temple bears a single line Prakrit inscription, which does not name the deity, but records that queen Mahadevi Cantamulas (wife of maharaja Ehuvula Camtamula) husband and children donated it (Narasimhaswami 1952: 1379). Sixthseventh century lajja-gauri gurines have been reported from a number of sites, including in Buddhist contexts (Brown 1990: 116) and the worship of the goddess continued into the seventeenth century as evident from nds in the Vijayanagara kingdom (Verghese 2000: ch. 8). An enduring legacy of the colonial period is the link that was established between forms of architecture and religious developments and it is intriguing that this connection has

346

Himanshu Prabha Ray

survived into the present. A prominent votary of this was James Burgess, the mathematics teacher turned archaeologist, who catalogued and documented a large number of sites in western and southern India. He assumed charge of the Archaeological Survey of Western India in 1873 and in 1881 this charge was subsequently expanded to include South India. Burgess was of the view that archaeology was the history of art, and that this was particularly valuable in the context of India where the written record is so imperfect, and so little to be relied upon (Fergusson and Burgess 1969[1880]: 36). He believed that an analysis of architectural styles could not only provide a rm chronology to the study of Indian history, but also help unravel religious developments and the relationship between Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. The Western caves aord the most vivid illustration of the rise and progress of all the great religions that prevailed in India in the early centuries of our era and before it. They show how Buddhist religion rose and spread, and its form afterwards became corrupt and idolatrous. They explain how it consequently came to be superseded by the nearly cognate form of Jainism and the antagonistic development of the revived religion of the Brahmins. (Fergusson and Burgess 1969[1880]: 166) Thus the connection between architectural form and religious change was rmly established in the nineteenth century, as was the myth that brick construction preceded that in stone. Henry Cousens visited Ter, about 45 kilometres east of Barsi, a great cotton centre, in 1901 and remarked on the extensive mounds around the town littered with brickbats and potshards. Remains of several brick-built Hindu, Jaina and Buddhist shrines and scattered sculptures were extant at the site and, in his report, Cousens describes the apsidal temple, which he claims was earlier a Buddhist caitya (shrine) on account of the brick sizes (17 x 9 x 3) and the form of the architecture, but was later converted to a Hindu temple of Trivikrama after addition of a at-roofed mandapa (hall). Other nds included four carved Buddhist stones used in the Jaina temple of Mahavira and Parsvanatha, a number of sati stones with a bent arm with open palm upon them, mutilated gures of Shiva, Shiva-Parvati, Bhairava and Ganapati of the Chalukyan period and a modern shrine with Vithobas footprints, while in a niche, in the back of this same temple, is an old image of Vishnu (Cousens 1904: 195204). Clearly then Ter was a multireligious site with a variety of religious architecture, which continued from the early centuries of the Christian era into the present. Epigraphs from the temples range between AD 1000 and the sixteenth century and a copperplate grant in Persian dated AD 1659 states that the Qazi of Ter ratied certain privileges to the head of the Teli community (Cousens 1904: 196). Subsequent archaeological excavations at the site unearthed the base of a large brick Buddhist stupa and an apsidal brick temple with a stupa in the apse and a wooden mandapa in front (Indian Archaeology A Review, 196768: 35). It is evident then that the mandapa formed an integral part of the apsidal structure and was not a later addition as suggested by Cousens. The Kapotesvaraswamy temple at Chezarla in Guntur district is another apsidal shrine with a mandapa, which is said to have been a converted Buddhist caitya. Alexander Rea

The apsidal shrine in early Hinduism

347

rst reported it (Progress Report of the Madras Archaeological Survey, December 1888 and January 1889: 12) and Cousens referred to its similarity with the shrine at Ter both in terms of its plan and the dimensions of bricks used (1904: 200). Since then, however, the excavations at Nagarjunakonda in the 1950s have added to our knowledge of early Hindu temples in Andhra and the anity between the temple at Chezerla and religious architecture of coastal Andhra is evident. Another apsidal structure that has undergone a similar trajectory of study and analysis is the Durga temple at Aihole (Plate 1), which was rst photographed in the middle of the nineteenth century by a British artillery ocer Biggs. The temples apsidal form led James Fergusson to suggest that it was a Buddhist structure subsequently appropriated for the worship of Shiva and by the 1860s the temple featured as an inglorious, structural version of a Buddhist caitya hall, appropriated by Brahmanical Hindus and buried under rubble at a site of the ancient Chalukya dynasty (Tartakov 1997: 6). As a result of subsequent investigation and research not only on the plan of the temple, but also its rich imagery, it is now evident that the Durga temple is one of nearly one hundred and fty temples built across 450 kilometres of the Deccan in the seventheighth centuries AD, albeit the Durga temple is the largest and most lavishly constructed monument dating to around AD 725 30. It is also apparent that the religious development of the period was diverse and included not only the setting up of Hindu temples, but also shrines of the Buddhists and

Plate 1 Durga temple at Aihole (courtesy: American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon).

348

Himanshu Prabha Ray

the Jainas (Tartakov 1997: 102). Thus the data do not support any association of the apsidal form with Buddhism and its subsequent appropriation; instead, the apsidal temple needs to be examined within its larger cultural context.

The Hindu temple: beginnings Perhaps the earliest temples are the two elliptical shrines at Besnagar (Vidisha) and Nagari (district Chittor) dated to the second century BC and rst century BC respectively (Deva 1995: 8). The Besnagar Brahmi pillar inscription on a Garuda pillar of Vasudeva, located 3 kilometres north-west of modern Vidisha and dated to the late second century BC states that it was commissioned by Heliodoros, son of Dion from Taxila, a worshipper of Vishnu. He came as the Greek ambassador from the court of Antialcidas the great king to Bhagabhadra, son of Kosi, the saviour, who was then in the fourteenth year of his prosperous reign (Sircar 1965: 66). An elliptical temple dated towards the end of the third century BC was unearthed during archaeological excavations at the nearby site. It had a brick plinth and a superstructure of wood, thatch and mud, but was raised on an earthen platform after damage by oods. To the east of this, seven pillars set on thick stone basal slabs were exposed in alignment with the Heliodoros pillar (Ghosh 1989: 62; Khare 1967). Two other elliptical constructions of the same period are known from Dangwada in central India. One of these with a plinth of boulders was identied as a Shiva temple and the other structure built of mud as a Vishnu temple (Chakrabarti 2001: 50). It is also evident that the beginnings of the Hindu temple were by no means restricted to the core area of the Ganga valley. Instead, in the eastern Deccan Buddhist shrines and Hindu temples formed a part of the landscape along with megalithic burial sites and memorials to the deceased. The Shiva linga at Gudimallam in Chittoor district dates to the secondrst centuries BC and was enshrined in an apsidal brick shrine dated to the rst century AD. Intense archaeological exploration at the conuence of the Krishna and Tungabhadra rivers has brought to light a remarkable series of brick temples. Two phases of structural activity marked the construction of temples at Veerapuram in the Krishna valley. Mostly square in plan, these contained pebble lingas and have been dated between the second and sixth centuries AD (Sarma 1982: 18). Similarly in Andhra, the earlier tradition of erecting memorials for the dead re-emerged in the form of chaya-stambhas or memorial pillars coinciding with the advent of the temple (Sarkar 1974). Srinivasan argues that, in spite of the experimentation evident in religious architecture, the iconography of early images is surprisingly condent and well established, as indicated by the adoption of multiple arms and heads. For example the Shiva linga from Bhita in Allahabad district dated to the second century BC is endowed with ve heads denoting the various aspects of the deity. Again the rst century BC Vishnu image from Malhar in central India has multiple arms and presents a form that continues well into the later periods (Srinivasan 1997: 185). The earliest evidence of an apsidal mud platform reinforced around the edge by three rows of dressed stones was unearthed in excavations at Ujjain Period II (500200 BC); however, its use is not clear (Banerjee 1965: 18). Another important site for our purposes is the site of Atranjikhera in district Etah in Uttar Pradesh located about 62 kilometres from

The apsidal shrine in early Hinduism

349

the site of Sankisa. One of the mounds outside the town revealed a brick-built apsidal temple with a gallery for circumambulation around a high platform meant for the deity. The structure of bricks measuring 37 x 23 x 6.3cm. is dated around 200100 BC and a terracotta plaque depicting gaja Lakshmi was found on the platform (Gaur 1983: 2567). Two apsidal structures were excavated at the site of Sonkh in Mathura district rst settled in 800 BC, though the earliest evidence for an apsidal shrine of baked brick in the habitation area dates to the rst century AD (Haertel 1993: 86). Apsidal temple no. 1 was reconstructed at least seven times in the rstsecond centuries AD, as evident from the distinct oor levels. Several terracotta plaques depicting Durga Mahisasuramardini (Durga killing the demon Mahisasura) and the goddess holding a child were found in the vicinity of apsidal temple 1 (ibid.: 120, 123), clearly indicating its Hindu aliation. A second apsidal temple (no. 2) dedicated to the Naga cult or snake worship was found 400 metres north of the main excavated area and dates to a somewhat earlier period in the rst century BC. In the rst phase the foundation of the apsidal structure was laid in mud brick (48 x 23 x 7cms) followed by layers of baked brick of the same size, surrounded by pillar bases and an enclosure wall. The second phase of the temple has been dated to the early centuries of the Christian era and at this time the aliation of the structure becomes evident. From the conspicuous accumulation of nds associated with the Naga cult, it is apparent that the temple was a major centre for the worship of the Naga cult (ibid.: 425). Nor is the Naga shrine from Sonkh unique in this regard, as several references in inscriptions indicate Naga worship in shrines, for example, at Maniyar Math near Rajagrha, where structural remains of a Naga temple were unearthed. This structure rested on at least two earlier strata of buildings, the older of which dates to the second rst centuries BC, though the precise ground plan is dicult to trace (Chandra 1938: 53). Thus the origins of the Hindu temple as established by archaeological data certainly predate references in the Puranas and inscriptions and the question arises as to what extent this architectural form drew upon an earlier tradition. The archaeological evidence from the Harappan site of Banawali in Haryana (Joshi 1999: 380) and the chalcolithic site of Daimabad in Maharashtra (Sali 1986: 111) shows that the association of an apsidal form with religious ritual/worship antedates the emergence of Hinduism and has a protohistoric antiquity. So Hinduism and Buddhism are perhaps drawing from older traditions.

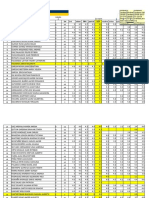

The development and expansion of the apsidal form It is no doubt true that some early shrines are undoubtedly associated with Buddhism, but there is evidence of other aliations as well, as shown above. In this section I shall discuss the distribution pattern of the apsidal shrine, both Buddhist and Hindu, across the Indian subcontinent in the historical period a period known for the expansion of religious architecture (Fig. 1). Brahmagiri in Karnataka is best known for three copies of minor rock edicts preserved on the upper surface at the bottom of the granite outcrop. About 200 metres to the south-east and further up the hillside there are remnants of an apsidal brick structure excavated in 1942 and again in 1947 and identied as a Buddhist shrine or caitya, though there is no trace of a stupa in the apse (Wheeler 19478: 1867). There is no evidence to date the caitya per se, but surviving bricks measure 17x 9x 33.5 (Wheeler

350

Himanshu Prabha Ray

19478: 187, fn 1) and are similar to those from Dharanikota in the Krishna valley dated from 400 BC to AD 400. A comparison with similar structures from the north is revealing.

Figure 1 Distribution of apsidal temples in India (after Sarkar 1978).

The apsidal shrine in early Hinduism

351

For example, at Sarnath, a brick apsidal caitya was recorded in the excavations not far from the Asokan pillar (Allchin 1995: 244, g. 11.15). Two more are known from Marshalls excavations at Sanchi (temples 18 and 40) and were dated by him to the Mauryan period (Marshall 1936: 11222). One of these (i.e. temple 40) was a stone construction. The number of apsidal shrines increases rapidly between the second century BC and the seventh century AD. These include both rock-cut caityas in the Deccan as well as structural temples with by and large Buddhist aliation found over an extensive region from Udayagiri in district Puri in Orissa (Indian Archaeology A Review 195859: 3840 Whitehead 1921) to Sanchi in central India and from Taxila in the north to Brahmagiri in the south. The apsidal temple on block D, Taxila, which dates from the early centuries AD, is the largest single structure at the site. Clearly a Buddhist monument, the plan of the apsidal temple is unusual in the screening of the caitya area from the assembly area, although it suggests ties to early apsidal halls such as the Lomas Rsi cave or early caitya halls such as at Kondivate (Huntington 1993: 116). Similar screen walls are also known from caitya 1 at Ramatirtham (Sarkar 1993: 42). Another region where Buddhism continued to ourish until the medieval period is Kashmir, where queen Didda (AD 9501003) erected a monastic site in her name and consecrated a bronze image of Lokesvara. Relevant for this paper is the site of Harwan in Srinagar district spread over a number of terraces overlooking the Dal lake. Archaeological excavations have unearthed an apsidal shrine located on the highest terrace well known for its unique terracotta tiles that pave the large courtyard. The tiles are decorated in low relief with geometric patterns, animals and human gures and at the back of the courtyard is a long platform, the tiles depicting a central frieze of emaciated seated ascetics (Mitra 1980: 111). An issue that may be briey discussed here relates to the survival as well as the continued construction of these apsidal shrines, both Buddhist and Hindu. We do know of Sanchis unbroken record as an important Buddhist monastic complex until the thirteenth century AD. Temple 18 at Sanchi dated to the seventh century AD seems to be one of the later structures built on an apsidal plan. Temple 40 at Sanchi dating to the Mauryan period was enlarged and converted into a rectangular mandapa (137 feet x 91 feet) about a century later with ve rows of ten octagonal stone pillars and a superstructure perhaps of wood (Deva 1995: 7). The latest additions to the structure were made in the seventheighth centuries AD. It is suggested that apsidal shrines retained an autonomous status in Andhra until the seventheighth centuries AD after which they generally formed a part of temple complexes, such as at Pitikayagulla and Satyavolu in Prakasam district, Papanasi group of temples at Alampur in Mahboobnagar district and the apsidal shrine at Peddachapalli in Cuddapah district built in the tenth century AD (Krishna Murthy 1983: 66). Extensive documentation by Sarkar indicates that apsidal temples continued to be constructed along the south-west coast in Kerala as well as the Tamil coast from AD 800 to 1800 (Sarkar 1978: 68). Within this time span, three phases of temple building are demarcated in Kerala. Starting from sanctums apsidal in plan, the shrine expanded to include a circumambulatory passage in the second phase dated from AD 1000 to 1300, while, in the third phase, a number of small apsidal shrines dedicated to Ayyapan came up in large temple complexes (ibid.: 100). Thus

352

Himanshu Prabha Ray

the continuity of the apsidal form is striking and it is worth noting that a majority of specimens of this form of temple architecture occur in peninsular India. Nor was this form replicated either in Sri Lanka or in Southeast Asia (Chihara 1996).

Nagarjunakonda: the religious landscape A region that provides crucial archaeological data on the religious landscape from the earliest Neolithic settlement in the third millennium BC to the sixteenth century is the secluded Nagarjunakonda valley shut in on three sides by oshoots of the Nallamalai Hill Range. More than thirty Buddhist establishments, nineteen Hindu temples and a few medieval Jaina shrines were unearthed in several seasons of archaeological excavations conducted at the site after its discovery in 1920 until its submergence in 1960 (Fig. 2). Early Buddhist religious architecture occurs throughout the valley, while Hindu temples were located mainly along the banks of the river Krishna and around the citadel area (Fig. 3). It

Figure 2 Archaeological sites in the Nagarjunakonda valley (after Sarkar and Misra 1999).

The apsidal shrine in early Hinduism

353

Figure 3 Details of excavations at Nagarjunakonda (after Sarma 1982).

is signicant that religious architecture of both the Hindus and the Buddhists was built on diverse ground plans and both used the apsidal form. At Nagarjunakonda, the apsidal shrine with a stupa in its apse is either associated with the Mahacaitya (sites 1 and 43) or forms a part of a residential enclosure for Buddhist monks (site 38) and in the latter case no stupa was found in the apse, leading to the suggestion that it may have enshrined either a Buddha image or Buddhapada found in its vicinity (Sarkar 1993: 778). In another case (site 9) the apsidal shrine located near the citadel formed a part of the monastery and was meant for the image of the Buddha (Sarkar and Misra 1999: 34). Site 85 was also situated close to the southern rampart wall and the monastic complex contained two caityagrhas (shrines) one oblong and the other apsidal both enshrining images of the Buddha (ibid.: 36). Sarkar and Misra suggest that apsidal shrines (sites 1 and 43) located in the vicinity of the main stupa or mahacaitya were later additions to the Buddhist establishment at Nagarjunakonda (1999: 33). Inscriptions on the oor of the shrines record the history of their foundations. The lay devotee Bodhisiri built the apsidal caityagrha for the welfare of her husband, his family and her maternal family at the vihara of Culadhammagiri and for the benet of monks from several regions such as Sri Lanka, China, Kashmir, Gandhara and so on (Vogel 192930: 22, no. F). The other apsidal shrine was also built for the

354

Himanshu Prabha Ray

benet of the monks from the dierent countries, but the donor in this case was Chamtisiri, the sister of the Iksvaku ruler Vasithiputa Siri Chamtamula (Vogel 192930: 21, no. E). Another apsidal shrine was found in the north-eastern part of the valley (site 24) and, in addition to its proximity to the monastery, shows two new features: one a circular image shrine and the other a memorial pillar raised in honour of the kings mother (Sarkar and Misra 1999: 37). The sculpture on the pillar depicts a lady seated on a high stool with a lady attendant standing nearby. Thus variations in apsidal shrines connected to Buddhist monastic complexes are evident and no single pattern prevailed. Similarly diverse are the ground plans of the Hindu brick temples at Nagarjunakonda, which may be broadly categorized as single shrines, shrines with pillared halls and the palace-temple of Sarvadeva designated as prasada in inscriptions (site 99). The apsidal form occurs both as a single shrine as well as a complex of either double apsidal shrines or one rectangular and the other apsidal structure (Sarkar and Misra 1999: 30). The Astabhujasvamin Vishnu temple (site 29) built in the third century AD had two shrines one oblong and the other apsidal each with a pillared hall in front and a larger pillared hall at the back. An inscription indicates that the temple enshrined a wooden image of eightarmed Vishnu and the name of the deity was also found inscribed on one of the several conch shells discovered at the site. Other structures include a dhvaja-stambha or agsta and two exquisitely carved pillars (ibid.: 25). The apsidal shrine clearly formed a part of the large temple complex surrounded by a brick enclosure and was aliated to Vishnu. A second temple complex was dedicated to Shiva as evident from the inscription on the dhvaja-stambha, which refers to mahadeva Puspabhadrasvamin enshrined in an apsidal temple (site 34; Fig. 4) built during the fourteenth regnal year of Ehuvala by his son Virapurusadatta and king Ehuvalas wife Kupanasiri (Sircar and Krishnan 19601: 1720). A large stepped tank built of masonry with a pavilion on the west was situated close to the shrine (Sarkar and Misra 1999: 26). Another large complex (site 78) was comprised of apsidal shrines in a row surrounded by an oblong enclosure with a rail, besides several shrines and a pillared mandapa. The aliation of this complex, however, remains uncertain, though the excavators suggest that it is more likely to be a Hindu temple complex on account of its location along the banks of the river (ibid.: 27). Thus archaeological excavations at Nagarjunakonda have identied nearly a hundred sites ranging from the prehistoric Stone Age to the medieval period, which provide details for an examination of the religious landscape incorporating a variety of stone and brick architecture. The earliest evidence of working in stone is indicated by Iron Age burials dated to the latter half of the rst millennium BC. Stone circles surrounded the burials or megaliths, which included both pit-burials and cists made of dressed stone covered with heaps of stone. In addition to the burials, the excavations unearthed the Hindu temples and Buddhist monastic complexes discussed above as well as twenty-two memorial pillars often associated with religious architecture. Another form of architecture comprised of at-roofed open pillared halls was found all around the valley at Nagarjunakonda. Thus the complex patterning of secular and religious space is evident. Nagarjunakonda is unique in that it provides a large corpus of inscriptions associated with Hindu as well as Buddhist architecture that allows insights into several aspects of

The apsidal shrine in early Hinduism

355

Figure 4 Plan of an apsidal temple at Nagarjunakonda (after Sarma 1982).

interaction between the community and religious architecture. The dynasty of the Iksvakus is prominently represented in the epigraphs, but royal patronage is indicated for only three of the nineteen Hindu temples, patronage for the other temples being provided by the community in general. An analysis of these records of donations indicates that in a majority of the Buddhist inscriptions the motive as stated by the donor relates to attainment of nirvana by the donor and the welfare and happiness of the world. A similar desire is evident in the inscription from the Puspabhadraswami temple, which was established by the kings wife and son for his long life and victory (Rupavataram 2003: tables 301). Thus the assumption by historians that kings established temples and donated to brahmanas to seek legitimization of their rule and that these religious shrines were agents of acculturation is not substantiated by the available data. Instead, the data from Nagarjunakonda clearly establish the intersection of diverse religious traditions; some were associated with communities settled earlier in the region and others were drawn in by movements of trading and craft groups and by Buddhist clergy as well as by internal dynamics associated with the emergence of the site as a centre of political power.

356

Himanshu Prabha Ray

Nagarjunakonda, as is evident from the archaeological record, participated in coastal networks as well as overland trading activity. It is also unusual in the varied secular architecture preserved at the site which includes a citadel, an elaborate water system, residential complex and what has been termed an amphitheatre. The region was home to a multi-layered society, which continued to absorb and introduce new elements in keeping with its needs. Nor was this unique, since an archaeological study in the Bastar region has identied a similar process (Postel and Cooper 1999). The site seems to have been deserted sometime in the medieval period and, at the time of its discovery, Nagarjunakonda was a wild and desolate place shut in by a ring of the rocky Nallamalai range. The nearest railway station was at Macherla, 20 kilometres from the site, and the remaining distance had to be traversed by bullock cart and by foot. The other alternative was to use the river for getting in and out of the valley. The hamlet of Pullareddigudem was located in the centre of the valley and was inhabited by Telugu Hindus and mobile groups such as the Lambadis and Chenchus (Longhurst 1938: 2).

Archaeology of a temple site: Gudimallam Gudimallam is a small village in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, but is signicant for this paper as archaeological excavations were undertaken in the sanctum of the Parasuramesvara temple that have provided an unbroken sequence of the temples long history (Sarma 1994). The beginnings of the Shiva temple date to the second century BC when the stone Shiva linga with an image of Shiva standing on a yaksa was enshrined within a square stone railing of 1.35m length on each side in the hypaethral shrine. The presence of cut bones of domestic sheep perhaps indicates animal sacrice (Indian Archaeology A Review 197374: 12). In Phase II dating from the rst to third centuries AD an apsidal brick temple was raised around the Shiva linga, but there is still no evidence for abhiseka or ritual anointing of the Shiva linga. In Phase III dating from the ninth century, elaborate arrangements were made for rituals and for regular anointing coinciding with structural activity that added several shrines to the temple complex (Sarma 1994: 31). Inscriptions dating from AD 845 to 989 record gifts made by individuals to the god Parasuramesvara. The earliest epigraph that refers to the construction of the temple in stone dates to AD 1127, but it is evident that by this time several structures, such as a number of subsidiary shrines, the brick enclosure wall and the gateway, had already been built. Thus the archaeological excavations at Gudimallam raise several signicant issues. These date the origins of the Hindu temple to the second century BC and indicate the use of stone prior to that of brick. More importantly the excavations conclude that, even though the temple complex underwent several structural variations, the Shiva linga enshrined as the object of worship in the sanctum remained unchanged from the second century BC onwards. In the past, scholars such as Krishna Murthy (1983: 66) had referred, on the basis of the apsidal form and the stone railing, to the shrine as a Buddhist caitya which was subsequently converted into a Hindu temple, but this is clearly refuted by the results of the excavations. Finally, archaeological excavations have documented changes in ritual

The apsidal shrine in early Hinduism

357

practice and elaboration and growth of the shrine through time, information that is largely absent in the inscriptional record. In the nal analysis it is hoped that this paper has succeeded in de-linking the connection often made between architectural form and religious practice and has stressed the naivety of such assumptions. If one accepts the Mauryan date for the apsidal caityas at Sanchi, Sarnath and Brahmagiri, then the apsidal form clearly had fourththird century BC beginnings. From the second century BC onwards it was used both for the Hindu temple, the Buddhist caitya and shrines of the Naga cult. There is little support for the traditional perception that Buddhism declined from the fourthfth centuries onwards and that the Hindu temple came into its own. On the contrary, the apsidal form continued to be added and expanded in both Buddhist and Hindu temple architecture. Nor for that matter is there any validity in the linear view of religious change projected by historians; instead, this paper has highlighted the complex religious landscape of sites such as Nagarjunakonda, which continued to be settled for more than 4,500 years and which are dotted with a multiplicity of religious architecture of varied aliation. The larger issue that this paper contests is the traditional notion of discontinuous historical epochs, with acculturation, Sanskritization and integration of tribal populations and other communities on the periphery at the behest of the political elite being the characteristic feature of the early medieval period dated between the sixthseventh and twelfththirteenth centuries AD. This model should instead be replaced by a dynamic process of accommodation and coexistence and the presence of multi-layered societies, as is evident from sites such as Nagarjunakonda. It is also important to recognize that almost every sacred spot was associated with more than one religion, be it Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism, Islam or Christianity. Second, local shrines and cult spots linked the village to the town and located these within a larger religious geography. Practices such as that of pilgrimage provided wider connectivity through movements of groups and communities, thereby linking several spots across the religious landscape. This larger picture and connectivity between sites is lost when archaeologists and historians focus narrowly on individual religious structures. Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University

References

Allchin, F. R. 1995. The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Banerjee, N. R. 1965. The Iron Age in India. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. Brown, R. L. 1990. A lajja-gauri in a Buddhist context at Aurangabad. The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 13(2): 116. Chakrabarti, D. 2001. The archaeology of Hinduism. In Archaeology and World Religion (ed. T. Insoll). London and New York: Routledge, pp. 3360. Chandra, G. C. 1938. Excavations at Rajgir: Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, 193536. Delhi: Manager of Publications, pp. 524.

358

Himanshu Prabha Ray

Chattopadhyaya, B. D. 1994. The Making of Early Medieval India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Chihara, D. 1996. Hindu-Buddhist Architecture in Southeast Asia. Leiden, New York and Cologne: E. J. Brill. Cousens, H. 1904. Ter Tagara. In Archaeological Survey of India Annual Report 19023. Calcutta: Government Printing Press, pp. 195204. Dagens, B. 1997. Mayamatam Treatise of Housing, Architecture and Iconography. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts & Motilal Banarsidass. Desai, D. 198990. Social dimensions of art in early India. In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Gorakhpur: Indian History Congress, pp. 2156. Deva, K. 1995. Temples of India. New Delhi: Aryan Books International. Fergusson, J. and Burgess, J. 1969 [1880]. Cave Temples of India. Delhi: Oriental Book Reprint Corporation. Gaur, R. C. 1983. Excavation at Atranjikhera. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. Ghosh, A. 1989. An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. Haertel, H. 1993. Excavations at Sonkh. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag. Huntington, S. L. 1993. The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jaina. New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill. Joshi, J. P. 1999. Religious and burial practices of Harappans: Indian evidence. In The Dawn of Indian Civilization (up to c. 600 B.C.) (ed. G. C. Pande). Delhi: Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy, and Culture; Centre for Studies in Civilization, pp. 37790. Khare, M. 1967. Discovery of a Visnu temple near the Helliodoros Pillar, Besnagar, District Vidisha. Lalit Kala, 13: 217. Krishna Murthy, K. 1983. Origin of Brahmanical apsidal shrines in Andhra. In Srinidhih: Perspectives in Indian Archaeology, Art and Culture (eds K. V. Raman et al.). Madras: New Era Publications, pp. 656. Longhurst, A. H. 1938. The Buddhist Antiquities of Nagarjunakonda, Madras Presidency: Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India No. 54. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. Marshall, J. 1936. A Guide to Sanchi. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. Meister, M. 2000. Ethnography and Personhood: Notes from the Field. New Delhi and Jaipur: Rawat. Mitra, D. 1980. Buddhist Monuments. Calcutta: Sahitya Samsad. Nandi, R. N. 1986. Social Roots of Religion in Ancient India. Calcutta: K. P. Bagchi. Narasimhaswami, H. K. 1952. Nagarjunakonda image inscription. Epigraphia Indica, 29(5): 1379. Nath, V. 2001. Puranas and Acculturation: A Historico-Anthropological Perspective. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. Paul, A. B. 2000. A study of the material remains of the early historic period discovered at Padri of Bhavnagar District. Pratnatattva, 6: 5366. Postel, M. and Cooper, Z. 1999. Bastar Folk Art: Shrines, Figurines and Memorials. Mumbai: Project for Indian Cultural Studies. Ray, H. P. 2004. The archaeology of sacred space: introduction. In Archaeology as History in Early South Asia (eds H. P. Ray and C. Sinopoli). New Delhi: Indian Council of Historical Research & Aryan Books International, pp. 35075. Rupavataram, A. 2003. An archaeological study of the temple in the eastern Deccan: 2nd century BC to 8th century AD. MPhil dissertation, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

The apsidal shrine in early Hinduism

Sali, S. A. 1986. Daimabad: 197679. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

359

Sarkar, H. 1974. Chhaya-stambha from Nagarjunakonda. In Seminar on Hero Stones (ed. R. Nagaswamy). Madras: Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology, pp. 199207. Sarkar, H. 1978. An Architectural Survey of Temples of Kerala. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. Sarkar, H. 1993. Studies in Early Buddhist Architecture, 2nd edn. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. Sarkar, H. and Misra, B. N. 1999. Nagarjunakonda. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. Sarma, I. K. 1982. The Development of Early Saiva Art and Architecture. New Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan. Sarma, I. K. 1994. Parasuramesvara Temple at Gudimallam. Nagpur: Dattsons. Sharma, R. S. 1987. Urban Decay in India. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. Shinde, V. 1994. The earliest temple of Lajjagauri? The recent evidence from Padri in Gujarat. East and West, 44(24): 4815. Sircar, D. C. 1965. Select Inscriptions Bearing on Indian History and Civilization, Vol. 1, no. 2. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. Sircar, D. C. and Krishnan, K. G. 19601. Two inscriptions from Nagarjunakonda. Epigraphia Indica, 34: 1720. Srinivasan, D. M. 1997. Many Heads, Arms and Eyes: Origin, Meaning and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. Leiden: Brill. Tartakov, G. 1997. The Durga Temple at Aihole: A Historiographical Survey. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Thapar, R. 2002. Early India: From the Origins to

AD

1300. London: Penguin.

Verghese, A. 2000. Archaeology, Art and Religion: New Perspectives on Vijayanagara. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Vogel, J. P. 192930. Prakrit inscriptions from a Buddhist site at Nagarjunikonda. Epigraphia Indica, 20: 136. Wheeler, R. E. M. 19478. Brahmagiri and Chandravalli 1947: Megalithic and other cultures in Mysore State. Ancient India, 4: 180310.

Himanshu Prabha Ray has degrees in archaeology, Sanskrit and ancient Indian history and teaches at the Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. In her research she adopts an inter-disciplinary approach for a study of seafaring activity in the Indian Ocean, of the history of archaeology and the archaeology of religion in South Asia. Her publications include Monastery and Guild: Commerce under the Satavahanas (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1986), The Winds of Change: Buddhism and the Maritime Links of Ancient South Asia (Oxford India Paperbacks, 2000), The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003) and edited volumes titled Tradition and Archaeology, with Jean-Francois Salles (New Delhi: Manohar, 1996), Archaeology of Seafaring: The Indian Ocean in the Ancient Period (New Delhi: Indian Council of Historical Research Monograph I, 1999) and Archaeology as History in Early South Asia, with Carla Sinopoli (New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2004).

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Jama MasjidDocument1 pageJama MasjidAbhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Du University's Value Addition Courses for 2022-23Document94 pagesDu University's Value Addition Courses for 2022-23Varsha SinghNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- New Doc 2018-08-14Document21 pagesNew Doc 2018-08-14Abhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Indian History CongressDocument4 pagesIndian History CongressAbhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- CNAS 19 01 ReviewsDocument22 pagesCNAS 19 01 ReviewsAbhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- IHC CircularDocument4 pagesIHC CircularAbhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Ihc 2011-15Document100 pagesIhc 2011-15Abhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- AILET 2008 Question Paper Explains Indian Law Entrance TestDocument44 pagesAILET 2008 Question Paper Explains Indian Law Entrance TestAbhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- (Oxford Ritual Studies) Ute Husken, Frank Neubert-Negotiating Rites-Oxford University Press (2011) PDFDocument309 pages(Oxford Ritual Studies) Ute Husken, Frank Neubert-Negotiating Rites-Oxford University Press (2011) PDFAnna KavalNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Regmi 07Document257 pagesRegmi 07Abhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- Drug Traffickiging - Behaviours, Types and OffensesDocument6 pagesDrug Traffickiging - Behaviours, Types and OffensesAbhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- Ancient Nepalese Sites ArchiveDocument36 pagesAncient Nepalese Sites ArchiveAbhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Avrospatt Sacred Origins of The Svayambhucaitya JNRC 13 2009 PDFDocument58 pagesAvrospatt Sacred Origins of The Svayambhucaitya JNRC 13 2009 PDFGB ShresthaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Beyond AfghanistanDocument11 pagesBeyond AfghanistanAbhimanyu KumarNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Serie Orientale Roma: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo OrienteDocument87 pagesSerie Orientale Roma: Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo OrienteAbhimanyu Kumar100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 1theravada Bud in Nepal KloppenbergDocument25 pages1theravada Bud in Nepal KloppenbergShankerThapaNo ratings yet

- Modern DramatistsDocument10 pagesModern DramatistsiramNo ratings yet

- Julius Bloom CatalogDocument143 pagesJulius Bloom Catalogjrobinson817830% (1)

- Ai Phonic Flash CardsDocument7 pagesAi Phonic Flash CardsNadzirah KhirNo ratings yet

- Top 15 Waterfalls Around the WorldDocument14 pagesTop 15 Waterfalls Around the WorldDaniel DowdingNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- U.P. Diksiyonaryong Filipino: Li-Pu-Nan - PNG Pol (Tag Lipon+an) : Malaking Pangkat NG Mga Tao Na MayDocument1 pageU.P. Diksiyonaryong Filipino: Li-Pu-Nan - PNG Pol (Tag Lipon+an) : Malaking Pangkat NG Mga Tao Na MayCCNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- How To Use The Browse Tree Guide: Background InformationDocument135 pagesHow To Use The Browse Tree Guide: Background InformationSamir ChadidNo ratings yet

- Soudal Soudaflex 40FC DataDocument2 pagesSoudal Soudaflex 40FC DatarekcahzNo ratings yet

- How To Spot A Fake aXXo or FXG Release Before You Download!Document4 pagesHow To Spot A Fake aXXo or FXG Release Before You Download!jiaminn212100% (3)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Gateway A2 Tests A and B Audioscript Test 1 Listening Exercise 8 A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: ADocument15 pagesGateway A2 Tests A and B Audioscript Test 1 Listening Exercise 8 A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: AAnonymous IkFaciNo ratings yet

- Lista Notas Ingles I - DerechoDocument6 pagesLista Notas Ingles I - DerechoMaria Jose Polanco UrreaNo ratings yet

- Slavoj Zizek - Organs Without Bodies - Deleuze and Consequences - 1. The Reality of The VirtualDocument8 pagesSlavoj Zizek - Organs Without Bodies - Deleuze and Consequences - 1. The Reality of The VirtualChang Young KimNo ratings yet

- Friends "The One Where Ross and Rachel... You Know"Document53 pagesFriends "The One Where Ross and Rachel... You Know"Matías Lo CascioNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Core of AdvaitaDocument1 pageThe Core of AdvaitakvrcNo ratings yet

- Snow White Play ScriptDocument9 pagesSnow White Play Scriptlitaford167% (3)

- Fonera 2.0n (FON2303)Document75 pagesFonera 2.0n (FON2303)luyckxjNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsDocument11 pagesPhilippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsRedenRosuenaGabrielNo ratings yet

- MonacoDocument7 pagesMonacoAnonymous 6WUNc97No ratings yet

- PantaloonsDocument32 pagesPantaloonskrish_090880% (5)

- Ibarra Character Analysis in Noli Me TangereDocument3 pagesIbarra Character Analysis in Noli Me TangereSokchheng Phouk0% (1)

- How Did The Augustan Building Programme Help To Consolidate Imperial PowerDocument4 pagesHow Did The Augustan Building Programme Help To Consolidate Imperial PowerMrSilky232100% (1)

- Syair Alif Ba Ta: The Poet and His Mission: Oriah OhamadDocument19 pagesSyair Alif Ba Ta: The Poet and His Mission: Oriah OhamadFaisal TehraniNo ratings yet

- First Cut Off List of Ete-Govt Diets, On 25/06/2010Document42 pagesFirst Cut Off List of Ete-Govt Diets, On 25/06/2010chetanprakashsharmaNo ratings yet

- Cape Literatures in EnglishDocument42 pagesCape Literatures in EnglishVenessa David100% (8)

- Reading 10-1Document7 pagesReading 10-1luma2282No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Free-Chapter From Born-Again DirtDocument4 pagesFree-Chapter From Born-Again Dirtmark russellNo ratings yet

- Essays On SanskritDocument3 pagesEssays On SanskritiamkuttyNo ratings yet

- Q2 Grade 7 Music DLL Week 1Document8 pagesQ2 Grade 7 Music DLL Week 1Wilson de Gracia100% (2)

- Basic Conducting PDFDocument2 pagesBasic Conducting PDFLaius SousaNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Pijat Laktasi Terhadap Produksi ASI Pada Ibu Menyusui Di Kelurahan Sendang Sari Kabupaten Asahan Tahun 2019Document7 pagesPengaruh Pijat Laktasi Terhadap Produksi ASI Pada Ibu Menyusui Di Kelurahan Sendang Sari Kabupaten Asahan Tahun 2019MAS 16No ratings yet

- 1200 Commonly Repeated Words in IELTS Listening TestDocument4 pages1200 Commonly Repeated Words in IELTS Listening TestMolka MolkanNo ratings yet

- When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult TimesFrom EverandWhen Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult TimesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)