Professional Documents

Culture Documents

House of Sert

Uploaded by

Furqon FranklinOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

House of Sert

Uploaded by

Furqon FranklinCopyright:

Available Formats

Spanish architect Josep Llus Sert (1902-1983) is perhaps best known for his build ings and urban-scale

projects. As a member of GATEPAC ("Group of Spanish Archite cts and Technicians for the Progress of Contemporary Architecture"), he was conc erned with the role of architects in city planning. And yet he was also a master of small-scale interior and furniture design. Some of his favorite forms were i nspired by vernacular houses. Editor Sert's own house at Punta Martinet was part of a cluster of nine houses built on a cape on the island of Ibiza, Spain between 1968 and 1971. He reinterpreted th e island's vernacular architecture which had long fascinated him. The six houses he designed are all different, each responding to its own program and topograph y. The existing stone terraces were conserved, giving the complex the air of an indigenous village. During his mature phase, Sert was clearly a Spartan interior designer, a creator of spaces of unquestionable visual beauty with a minimum of artifacts or identi fiable pieces as individual objects. These spaces were motivated by a remarkable proportional coherence and were gene rally free of any rhetorical whim that might refer either to the past or to what was currently in vogue. Furnishings were subordinated as much as possible to th e architecture, with the exception of certain classic pieces such as Thonet chai rs and armchairs, or those from the traditional repertoire: either American Wind sor chairs or the ones used in the peasant houses on Ibiza. Walls and ceilings were consistently painted in white, thus becoming neutral pic torial backgrounds that enabled chromatic accents to be provided by carpets, tap estries, and especially paintings, which commanded all the attention of the vert ical plane. Objects with volume, such as ceramic pieces or statuettes, were placed on ledges or in recesses, also designed to break the vertical plane. Hence, the strategic placing of paintings and objects always responded to aesthetic reasons, no matt er what their monetary or sentimental value, and dominated the visual effect fro m their preeminent position. Integrating the Object The immediate victims of Sert's purging of all historical furniture were the pie ces with individual names: buffet, chest, cupboard, chest of drawers, etc. These were type-objects originally formed in accordance with their function and the b est construction method, and which, owing to their very autonomous nature, had i nevitably been made to play out their roles in the distinct decorative style of each historical period. For example, when 18th-century eclecticism also made its way into interiors, a v ariety of styles coexisted, depending on the rooms and the whim or extravagance of the owner of the house. This exacerbated the ornamental weight of the piece o f furniture and diminished its practical value, which only the simplest and olde st versions in remote country houses managed to maintain. Restraint and emptiness were among the overall tendencies of the interior archit ecture by GATCPAC members: their reaction to the eclecticism of the period and t he excesses in ornaments, tapestries, and draperies which so characterized Art N ouveau. One of the earliest symptoms of this attitude of rejection was the abund ance of built-in furnishings. Aside from the space that these saved, in Sert's case one could go so far as to speak of a refusal, or at least a reluctance, to design any independent object s egregated from an architectural medium. His work includes numerous examples of m

asonry furniture, either freestanding or wall-attached, and designs of wooden fu rnishings treated like masonry, on account of their whiteness and the unusual th ickness of their shelves. Brick Fireplaces It was in the small residential development of Punta Martinet where white brick fireplaces took on a significant role. Their position was repeated in five of th e six houses, always at the connecting point between the beginning of a staircas e or hallway and the living room, so that the latter was approached by circling the fireplace. This feature is surprisingly shared by the famous "prairie houses" of Frank Lloy d Wright, which are yet so different in silhouette and layout. The fireplace hea rth always faced the longest dimension of the room and consisted entirely of a n umber of ledges and shelves that joined it to the wall. In this way, it closed off the space without opacity at its shorter end. It shou ld be added that the living rooms in all these houses are rectangular spaces tha t run parallel to a terrace with a view, so that one side is completely glazed. The design of the different fireplace variations is characterized by a compositi on of spaces and solids controlled by regulatory outlines, like a facade. In fac t, Sert used this ordering device in the majority of his shelf and fireplace des igns, where there were potential sections with vertical and horizontal lines for either constructive or functional purposes. Wall Benches Wall-attached benches are a clear case of furniture design being subordinated to architecture. The fireplaces of the houses at Punta Martinet were always accomp anied by masonry benches that lined the entire wall to which the chimney was joi ned. This feature was clearly inspired by the traditional peasant houses of Ibiz a, in which both the porxo, or porch, and the living room (often a porch which f ound itself indoors, when surrounded by new rooms), always included a long bench . The bench's function was multiple, as it was used without distinction for family meals, community work, and receiving visits, even for the festeig or courtship of girls of marrying age. Because, conceptually speaking, it was so closely link ed to the wall support and so little restricted to seating, the bench mass was o ccasionally broken up with carved steps to help reach the adjoining rooms, smoot hing the changes in level inside the peasant houses. This is one of the most attractive features of traditional lbizan houses: they g rew over time, through a modular system, by which cases, or attached rooms, were added to the walls of the existing house with scarcely any effort made to level them out. Given the fascination which lbizan peasant houses had for Sert and his GATEPAC c olleagues, it should come as no surprise that the architect introduced this benc h typology into the main room of each of his houses on the island, which on the other hand, stood out for their perfectly contemporary organization of space. But what is most astonishing about these benches, long enough to amply surpass t he useful size for the domestic get-together, is their abstract condition of min imal yet rhetorical elements, like a bend in the wall or a baseboard that just h appens to let one sit down on it. Their usefulness was only made complete when the entire space was full of people

, as occurs during a crowded gathering, when, after the living room area fills u p, guests spill over onto the terrace, which in each of these houses is an openair replica of the living room, with the two running parallel. What we have then is an enormous bench covered with large made-to-measure cushio ns, thus increasing the comfort of its Ibizan predecessor. It encourages social life by responding to a living room concept much more open and democratic than t he classic urban three-piece suite which, while more or less spacious, invariabl y leads to conversational crossfire. It is hardly surprising that Sert decided to add Ibiza-inspired benches to his t wo houses in the United States (albeit with a wooden structure) 20 years before doing so to the houses at Punta Martinet.

You might also like

- Elements To Bear in Mind About Ponce ArchitectureDocument8 pagesElements To Bear in Mind About Ponce ArchitectureJorge Ortiz ColomNo ratings yet

- Tugendhat House ResearchDocument6 pagesTugendhat House ResearchTeodora VasileNo ratings yet

- GEORGE TSIHLIAS ANALYZES VICTOR HORTA'S MAISON TASSELDocument21 pagesGEORGE TSIHLIAS ANALYZES VICTOR HORTA'S MAISON TASSELAndreea-daniela BalaniciNo ratings yet

- Philippine Spanish Interior DesignDocument43 pagesPhilippine Spanish Interior Designmirei100% (10)

- House TicinoDocument2 pagesHouse TicinoCopperConceptNo ratings yet

- PRESENTAION On Architect Mies Van Der RoheDocument74 pagesPRESENTAION On Architect Mies Van Der RoheAshish HoodaNo ratings yet

- Santiago CalatravaDocument7 pagesSantiago CalatravaBhaskar TGNo ratings yet

- The Brochure Series of Architectural Illustration, Volume 01, No. 05, May 1895 Two Florentine PavementsFrom EverandThe Brochure Series of Architectural Illustration, Volume 01, No. 05, May 1895 Two Florentine PavementsNo ratings yet

- HortaDocument32 pagesHortaMilagritos VillafuerteNo ratings yet

- 18th-19th Century Family Houses Architectural FeaturesDocument3 pages18th-19th Century Family Houses Architectural FeaturesHustiuc RomeoNo ratings yet

- Frank LLoyd WrightDocument9 pagesFrank LLoyd Wrightmarija.labady-cukNo ratings yet

- Brooks 1979 - Wright and The Destruction of The BoxDocument9 pagesBrooks 1979 - Wright and The Destruction of The BoxAna Mae ArozarenaNo ratings yet

- Robert Venturi and Postmodernism - Vanna Venturi House and Guild HouseDocument9 pagesRobert Venturi and Postmodernism - Vanna Venturi House and Guild HouseAnqa ParvezNo ratings yet

- The Philippines: The Filipino Bahay Kubo, Where Form Does Not Necessarily Follow FunctionDocument1 pageThe Philippines: The Filipino Bahay Kubo, Where Form Does Not Necessarily Follow FunctionNicole LimosNo ratings yet

- Group 8 - Victorian ReportDocument87 pagesGroup 8 - Victorian ReportRico, Maria NicoleNo ratings yet

- Group7 RusticDocument23 pagesGroup7 RusticRico, Maria NicoleNo ratings yet

- Theory of Design: Design Principles and Philosophies of F.L.WrightDocument18 pagesTheory of Design: Design Principles and Philosophies of F.L.WrightPreethi HannahNo ratings yet

- More Than The Sum of PartsDocument28 pagesMore Than The Sum of PartsLeonardo StasiukiNo ratings yet

- The Brochure Series of Architectural Illustration, Volume 01, No. 05, May 1895 Two Florentine Pavements by VariousDocument18 pagesThe Brochure Series of Architectural Illustration, Volume 01, No. 05, May 1895 Two Florentine Pavements by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- History PDFDocument11 pagesHistory PDFShweta ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Living Room - WikipediaDocument11 pagesLiving Room - WikipediaShruthi AmmuNo ratings yet

- British Interior House Styles: An Easy Reference GuideFrom EverandBritish Interior House Styles: An Easy Reference GuideRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- American ArchitectureDocument36 pagesAmerican ArchitectureChristina VitaleNo ratings yet

- The Bungalow Book: Floor Plans and Photos of 112 Houses, 1910From EverandThe Bungalow Book: Floor Plans and Photos of 112 Houses, 1910No ratings yet

- Old English Chintzes - Chintz in Relation to Antique FurnitureFrom EverandOld English Chintzes - Chintz in Relation to Antique FurnitureNo ratings yet

- Art Nouveau's First Fully Developed BuildingDocument16 pagesArt Nouveau's First Fully Developed Buildingandreina callejasNo ratings yet

- Westgate Lifesrichpattern 2007Document10 pagesWestgate Lifesrichpattern 2007EmilyNo ratings yet

- OASE 75 - 203 Houses of The Future - Part2Document1 pageOASE 75 - 203 Houses of The Future - Part2Izzac AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Weissenhofsiedlung Progressive Architecture 10-1988Document12 pagesWeissenhofsiedlung Progressive Architecture 10-1988RominaVillegasNo ratings yet

- Edwardian House: Original Features and FittingsFrom EverandEdwardian House: Original Features and FittingsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Courtyard Housing: Environmental Approach in Architectural EducationDocument18 pagesCourtyard Housing: Environmental Approach in Architectural EducationVedad KasumagicNo ratings yet

- Victorian City and Country Houses: Plans and DetailsFrom EverandVictorian City and Country Houses: Plans and DetailsRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- The Victorian HouseDocument42 pagesThe Victorian HouseManjeet CinghNo ratings yet

- Folk Architecture in The PhilippinesDocument15 pagesFolk Architecture in The PhilippinesAarøn AlarcaNo ratings yet

- Arts and Crafts MovementDocument10 pagesArts and Crafts MovementKavyaNo ratings yet

- Frank Lloyd Wright: JUNE 8, 1867 - APRIL 9, 1959Document33 pagesFrank Lloyd Wright: JUNE 8, 1867 - APRIL 9, 1959ABEER NASIMNo ratings yet

- The Experience of SpaceDocument12 pagesThe Experience of Spacevictoria dolfoNo ratings yet

- Louis Kahn's Fisher HouseDocument5 pagesLouis Kahn's Fisher HouseSuryadi Chandra0% (1)

- Folk Architecture in The PhilippinesDocument15 pagesFolk Architecture in The PhilippinesEldrine BalberonaNo ratings yet

- For My Report (Arts)Document19 pagesFor My Report (Arts)Jezrheel Cabrera TalledoNo ratings yet

- Furniture of the Renaissance to the Baroque - A Treatise on the Furniture from Around Europe in this PeriodFrom EverandFurniture of the Renaissance to the Baroque - A Treatise on the Furniture from Around Europe in this PeriodNo ratings yet

- Interiordesignhistory 180606192312Document99 pagesInteriordesignhistory 180606192312Vriti Sachdeva100% (1)

- Folk Architecture: Submitted By: Kristine Mae PalaoDocument15 pagesFolk Architecture: Submitted By: Kristine Mae Palaozeno phyxxNo ratings yet

- Philip Johnson Thesis HouseDocument7 pagesPhilip Johnson Thesis Housefjgmmmew100% (2)

- Architectural StylesDocument16 pagesArchitectural StylesJames Nicolo AltreNo ratings yet

- Arts and Crafts Movement, Red HouseDocument9 pagesArts and Crafts Movement, Red HouseKavyaNo ratings yet

- Furniture Making - Designs, Working Drawings, and Complete Details of 170 Pieces of Furniture, with Practical Information on Their ConstructionFrom EverandFurniture Making - Designs, Working Drawings, and Complete Details of 170 Pieces of Furniture, with Practical Information on Their ConstructionNo ratings yet

- Zeinstra Houses of The FutureDocument12 pagesZeinstra Houses of The FutureFrancisco PereiraNo ratings yet

- The Masterpieces of Thomas Chippendale - A Short Biography and His Famous CatalogueFrom EverandThe Masterpieces of Thomas Chippendale - A Short Biography and His Famous CatalogueNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument25 pagesUntitledСофіяNo ratings yet

- Living Outside The Box: Mary Otis Stevens and Thomas McNulty's Lincoln HouseDocument10 pagesLiving Outside The Box: Mary Otis Stevens and Thomas McNulty's Lincoln House李家清No ratings yet

- Works of FLW, Ward Willits House Case StudyDocument11 pagesWorks of FLW, Ward Willits House Case StudyArchana Sakharwade100% (1)

- LE CORBUSIER (Black Background)Document48 pagesLE CORBUSIER (Black Background)Devendra YadavNo ratings yet

- CVs All 7 ExpertsDocument33 pagesCVs All 7 ExpertsPoshan DhunganaNo ratings yet

- ISWARA DEWATA HOTEL SITE MEETING MINUTESDocument7 pagesISWARA DEWATA HOTEL SITE MEETING MINUTEScmu baliNo ratings yet

- IN436706 - IFFCO Palm Jumeirah Villa - Inspection Dec 13, 2018Document6 pagesIN436706 - IFFCO Palm Jumeirah Villa - Inspection Dec 13, 2018PatrichNo ratings yet

- CFix AVI Thermo KorbDocument12 pagesCFix AVI Thermo KorbJoeNo ratings yet

- Thermo 80 energy efficient tilt & turn windowsDocument8 pagesThermo 80 energy efficient tilt & turn windowsJose VicenteNo ratings yet

- Advanced Construction Technologies and Materials CongressDocument3 pagesAdvanced Construction Technologies and Materials Congresssarveshfdk48No ratings yet

- RSHP Selected Projects PDFDocument222 pagesRSHP Selected Projects PDFJohanArch100% (1)

- GLT - ENG.ME - ST.03 Insulation Hot Stainless Steel Vessels v0Document9 pagesGLT - ENG.ME - ST.03 Insulation Hot Stainless Steel Vessels v0clintNo ratings yet

- ICC-ES Evaluation Report ESR-1008: Halfen GMBHDocument26 pagesICC-ES Evaluation Report ESR-1008: Halfen GMBHmurdicksNo ratings yet

- Roof Truss Installation Guide V1.4 2015Document36 pagesRoof Truss Installation Guide V1.4 2015DM Andrade0% (1)

- Rawlinsons Construction Cost Guide 2020 - (Detailed Prices)Document4 pagesRawlinsons Construction Cost Guide 2020 - (Detailed Prices)ZoeNo ratings yet

- Occupancy and Occupant LoadDocument47 pagesOccupancy and Occupant LoadGellaii Aquino QuinsaatNo ratings yet

- 11-Ground Floor Foundation LayoutDocument1 page11-Ground Floor Foundation LayoutUzair QuraishiNo ratings yet

- QS Masonry Works SLS 573 SummaryDocument1 pageQS Masonry Works SLS 573 SummaryRanjith EkanayakeNo ratings yet

- NATIONAL BUILDING CODE 2016 AMENDMENTSDocument25 pagesNATIONAL BUILDING CODE 2016 AMENDMENTSPRADIP DUNGDUNG100% (1)

- Illawarra Grand 36 Brochure Plan 1Document2 pagesIllawarra Grand 36 Brochure Plan 1JITUL MORANNo ratings yet

- RLS Batm-2 2 0Document1 pageRLS Batm-2 2 0MulawarmanNo ratings yet

- 3 Part Csi Specification 12-11Document6 pages3 Part Csi Specification 12-11abbNo ratings yet

- Second Floor Plan Ground Floor Plan: (Motel) (Motel)Document1 pageSecond Floor Plan Ground Floor Plan: (Motel) (Motel)Gil Joshua Medina FloresNo ratings yet

- BESTWAY CEMENT LIMITED INSPECTION CHECKLIST FOR REINFORCED CONCRETEDocument4 pagesBESTWAY CEMENT LIMITED INSPECTION CHECKLIST FOR REINFORCED CONCRETEbabarNo ratings yet

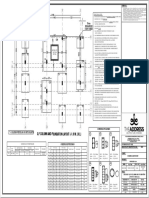

- Typical Working Drawing WakafDocument1 pageTypical Working Drawing WakafAzmi PittNo ratings yet

- Neo-Expressionist Architecture Styles and FeaturesDocument13 pagesNeo-Expressionist Architecture Styles and FeaturesNeeraj JoshiNo ratings yet

- DATA BOOK FOR CONSTRUCTION PROJECTSDocument66 pagesDATA BOOK FOR CONSTRUCTION PROJECTSvishnukesavieam10% (1)

- Frei Paul OttoDocument42 pagesFrei Paul Ottosrivalli totakura100% (1)

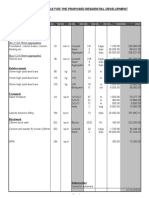

- Material Schedule Breakdown for Proposed Residential DevelopmentDocument13 pagesMaterial Schedule Breakdown for Proposed Residential Developmentemmanuel100% (1)

- Architectural Design 3 - Lecture 1 - OrientationDocument11 pagesArchitectural Design 3 - Lecture 1 - OrientationBrigitte ParagasNo ratings yet

- Ultratech Cement Particulars Test Results Requirements of - CompressDocument1 pageUltratech Cement Particulars Test Results Requirements of - CompressJerry TomNo ratings yet

- Cosh41 AttachmentDDocument3 pagesCosh41 AttachmentDajmaluetNo ratings yet

- DCI CatalogDocument20 pagesDCI CatalogAbu AlAnda Gate for metal industries and Equipment.No ratings yet

- Bhagwati School Strap Report AnalysisDocument60 pagesBhagwati School Strap Report AnalysisReverse Minded100% (1)