Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Beware The Windigo

Uploaded by

Καταρα του ΧαμOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Beware The Windigo

Uploaded by

Καταρα του ΧαμCopyright:

Available Formats

Beware The Windigo

by Steve Pitt Transylvania has Count Dracula. Scotland has the Loch Ness monster. Florida has the Sasquatch Skunk Ape of the Everglades and Canada has the Windigo! What is a Windigo? It is something like a werewolf on steroids. It stands more than six metres tall in its bare feet, looks like a walking corpse and smells like rotting meat. It has long, stringy hair and a heart of ice. Sometimes a Windigo breathes fire. It can talk, but mostly it hisses and howls. Windigos can fly on the winds of a blizzard or walk across water without sinking. They are stronger than a grizzly bear and run faster than any human being, which is bad news because human flesh happens to be a Windigo's favourite food. A Windigo's appetite is insatiable. Indeed, the more it eats, the hungrier it gets. The worst thing of all is that a Windigo was once a human being. There are several ways someone can turn into a Windigo. You might be cursed by a shaman, or bitten by another Windigo. The most common cause, however, is to be starved over a long period of time. If starved long enough, some people turn into Windigos to survive. If a Windigo reverts to its human form, it often becomes overcome with remorse and begs to be killed before it turns Windigo again.

ILLUSTRATION: MARY ANN CAIBAIOSAI Ojibway artist Mary Ann Caibaiosai's depiction of the Windigo. Stories of the beast were often used to keep children from straying too far from villages.

All right, before you run out and buy 100 metres of electrified barbed wire to fortify your house, please note that the Windigo is an Algonquian legend. The Algonquian is the largest Aboriginal language group in Canada, and includes the Abenaki, Algonkin, Blackfoot, Cree, Mik'maq and Ojibwa. Not surprisingly then, there are hundreds of stories and even at least 45 recorded variations of the word Windigo. Just a few versions of the name are Atchen, Chenoo, Kewok, Wheetigo, Windikouk, Wi'ntsigo, Wi'tigo, and Wittikka. The Canadian Encyclopedia describes Windigo as a "spirit...that takes possession of vulnerable persons and causes them to engage in various antisocial behaviours, most notably cannibalism."

The origin of the Windigo legend fades far back into the prehistory oral tradition of the Algonquian. The first known written account of this legendary creature was by Paul Le Jeune, a Jesuit missionary serving in Quebec in the early 17th century. In 1636, Father Paul sent a dispatch to his superiors in Rome complaining about a local native woman who, in a spiritual trance, warned that an Atchen was coming to attack a nearby village. The priest informed his superiors that an Atchen was "a sort of werewolf." Judging by the tone of his letter, Father Paul was not in fear for his life but highly annoyed with the woman because her dreams were frightening his hard-won converts. The first English record of the Windigo came from James Isham, a Hudson's Bay Company employee who was stationed at York Factory (now Manitoba) from 1743 to 1749. Isham kept a journal of his experiences and eventually published his notes as Observations of Hudson's Bay. Among the Cree words included in his letters was the noun "Whit te co", which Isham translated to mean "the devil."

Virtually every human society has a horror of cannibals. Being condemned to eat human flesh was considered a punishment by God in the Old Testament. Deuteronomy 28:53 is one particularly chilling example: "Even the most gentle and sensitive man among you will have no compassion on his own brother or the wife he loves or his surviving children, and he will not give to one of them any of the flesh of his children that he is eating." Romans who could happily watch thousands of helpless people being devoured by wild animals in the arena would seek out and kill unarmed Christians because their Pagan emperors accused them of cannibalism. Virtually every indigenous people European explorers came in contact with was charged with cannibalism as an excuse to "civilize" them. At the same time, humans have always been fascinated by cannibals and they appear regularly in literature. Greek mythology starts off with the Titan Chronos routinely eating his children until one of them, Zeus, manages to survive long enough to kill him. In Shakespeare's tragedy, Titus Andronicus, the title character serves his enemy, Tamora, her own sons cooked in a meat pie. In 1875, Mark Twain wrote a humorous story called Cannibals in the Cars about a group of "civilized" businessmen who, after their train becomes snowbound, debate logically about which of them deserves to be killed and eaten so that the others may survive. The horror/humour trend lives on today with popular movies like Soylent Green, Eating Raoul and Hollywood's most popular cannibal, Hannibal Lecter, who now has three blockbuster movies on his plate. But the Windigo legend is far more than an Algonkin's or Cree's idea of entertainment. The legend actually worked on four separate levels, each serving a different personal need. At the practical level, the Windigo was a boogeyperson used by parents to keep their children from wandering too far from home. Like Grimm Brothers fairy tales, many Windigo legends begin with someone wandering off too far in the woods and coming face to face with their worst nightmare. Children were told to stay close to home or the big bad Windigo would get them. At a materialist level, the Windigo legend explained why cannibalism occurred. The Algonkin and other natives lived in an extremely harsh environment. Starvation, especially during the winter months, was a fact of life. After weeks of suffering, occasionally one or sometimes a group of people would resort to cannibalism to survive. One written account dates to 1823 when Major H. Long, a scout for the United States Army, made an excursion into native territory near Lake of the Woods in Ontario. In his memoirs, he records: "A more gloomy name is that of Cannibal or Wdig Lake, which is derived from the unnatural deed in its vicinity. It is said that a party of Indians belonging to the schkkmg Wnnwk, or Band of the Crossridge, were once encamped near this ridge in the year 1811, and were quite destitute of provisions; they amounted to about 40; their numbers diminished through famine, the survivors feeding on the bodies of their deceased relations. Finally there remained but one woman, who had subsisted on the bodies of her own husband and children, whom she had killed for this purpose. She was afterward met by another party of Indians, who, sharing in the common belief that those who have once fed on human flesh, always hunger for it, put an end to her existence." It is interesting to note that the Indians did not see cannibalism as the desperate act of a sane person but as a chronic disease of a deranged person. At first, white people scoffed at this notion but by the late 19th century, scientists were beginning to notice that symptoms like depression, loss of appetite and fear of turning into a Windigo were consistent in many First Nations patients. They also noticed that these symptoms were almost always triggered by an extended period of starvation and isolation in the wilderness. Eventually researchers even coined a medical mental condition called Windigo Psychosis that was peculiar to the Algonquian-speaking Indians but very similar to patients suffering from lycanthropy (people who thought they were werewolves) in Europe. First Nations people believed that the only cure for a Windigo was death. Even when a person appeared normal, if he or she was suspected of being a Windigo they were at the very least ostracized by their fellow tribe members and more often killed. It was also believed that a Windigo could return from the dead if the heart was not destroyed completely.

James Carnegie, Earl of Southesk, wrote a diary about his journey through Saskatchewan and the Rocky Mountains in 1859 and 1860 and recorded this incident: "On the neck of land a Salteaux Indian was put to death under singular circumstances. Being affected by some sort of madness and spoke to no one, and apparently ate nothing for a month. His tribe took the idea that he was a cannibal, and after wounding him severely they buried him before life was extinct. Many hours later the unhappy wretch was heard moving in his grave, so they dug him up and burned him to ashes." In most cases, it was believed that white people were immune to becoming either victims of or Windigos themselves but John Long, a Hudson's Bay trader travelling through Ontario in the year 1799, came across a white Windigo. The victim did not become a towering, fire-breathing monster but he did exhibit the classic symptoms of Windigo Psychosis. Long met a Hudson's Bay trader by the name of Fulton who had been working the area of Skunks-Head Lake (in the vicinity of Lake Nipigon). While there, Fulton was shocked to receive a complaint by a chief that an evil spirit had entered one of Fulton's men, Charles Janvier, and killed one of the chief's kinsmen. Sent out to trade, Janvier and two other white men, Franois St. Ange and Lewis Defresne had been camping deep in the wilderness and ran out of food. They were on the verge of starving to death when a passing native hunter discovered them and gave them what little food he had. The native stayed overnight to make sure the white men were all right by keeping the fire burning. Unfortunately, instead of feeling gratitude, Janvier felt only more hunger. He asked the native to help set a large log on the fire. As the hunter leaned forward to pick up his end of the log, Janvier struck him dead with an axe. Janvier then hacked up his victim and put some of the pieces in a large cauldron over the fire. Janvier's actions completely terrified his white companions but they were too weak to resist him. He also threatened them with the same fate unless they shared in the cannibal meal and took an oath before God that they would never reveal the incident to any other living being. When the native's meat finally ran out, Janvier killed St. Ange and ate him too. Finally feeling strong enough to travel, Janvier forced Defresne to drag him back to camp in the hunter's sleigh. At first Fulton suspected nothing but the native chief's accusation, St. Ange's disappearance and Janvier's suspicious behaviour caused him to interrogate the two men until Defresne finally confessed. Fulton's reaction to cannibalism was similar to how some natives reacted to such situations. He had Janvier shot and buried on the spot. At the religious level, the Windigo legend helped explain why bad things happened to good people. The Algonquian were highly skilled at surviving in the wilderness but occasionally an individual or even a whole party would fail to return from the hunt. It was hard for those remaining behind to accept that their best hunter or most experienced forager could simply disappear or get lost. Their spiritual world was populated by a multitude of spirits ranging from the great Manitous to the simple spirits of animals that lived in the wilderness. There were also evil spirits like the Windigos and Pauguk, a flying skeleton that is a version of the Grim Reaper. And finally, there were trickster spirits who really meant no harm but their pranks had a habit of bringing grief to mortal humans. In such a world, no one simply got lost. Things happened for a reason and just as most pre-20th century Christians fervently believed that a real Devil was ever ready to snare the unwary, many pre-20th century Algonquian-speaking Indians were equally convinced that Windigos were real and always hungry. Edward Umfreville, another Hudson's Bay Company employee, noted that the Cree who lived along the North Saskatchewan River in the 18th century tried to bribe the Windigo by offering him gifts. "Of him they are very much in fear, and seldom eat anything or drink any brandy, without throwing some into the fire for Whit-ti-co. If any misfortune befalls them they sing to him, imploring his mercy, and when in health and prosperity do the same, to keep him in good humour."

Virtually any religion consists of similar gestures as fearful humans try to keep on the good side of their supernatural counterparts. The fourth level the Windigo legend operated within the First Nations mindset was as a philosophical outlook. As previously mentioned, most First Nations people lived a precarious existence where extreme mental and physical self-control were required to survive. In the 18th and 19th centuries, many white writers commented in amazement on how First Nations people could endure hardship and emotional tragedy with apparent indifference. Of course Indians felt pain and mental anguish as deeply as any other human being but they had been raised in a culture of self-discipline. Basil H. Johnston is an Ojibwa scholar, lecturer and author of 11 books about First Nations legends and mythology. In his book, The Manitous, he devotes an entire chapter to the Windigo as both a myth and a philosophy. Almost all Windigos are self-created, Johnston states. A Windigo was a human whose selfishness has overpowered their self-control to the point that satisfaction is no longer possible. That is why Windigos are always hungry no matter how much they eat. In former times Ojibwa people would strive to keep their selfishness under control. If there was no food, the entire community went hungry. If food was plentiful, they still would take only what they needed to avoid building up a taste for self-indulgence. To an Ojibwa's point of view, any overindulgent habit is self-destructive and any self-destructive habit is Windigo. Johnston says that over the last 200 years, a new breed of Windigo has appeared in North America. Multi-national corporations have taken over the landscape like the giant cannibals of Indian legend. Driven by profit, the multinationals devour resources and even each other not for need but greed. Yet instead of looking at these Windigos in horror, we admire people who single-mindedly amass more wealth than they can ever possibly use. "Look at even today's hockey players," Mr. Johnston said in a phone interview. "Even the most mediocre expect millions."

You might also like

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Turkey Condemns 'Genocide' VoteDocument2 pagesTurkey Condemns 'Genocide' VoteΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Evil Spirit Made Man Eat Family, A Look Back at Swift RunnerDocument3 pagesEvil Spirit Made Man Eat Family, A Look Back at Swift RunnerΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Turkey Threatens To Expel 100,000 Armenians Over Genocide' RowDocument2 pagesTurkey Threatens To Expel 100,000 Armenians Over Genocide' RowΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Cannibals and Clowns of The Anishinabe and Other North American Native GroupsDocument10 pagesCannibals and Clowns of The Anishinabe and Other North American Native GroupsΚαταρα του Χαμ100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Obama Declines To Call Armenian Deaths in World War I A ''Genocide''Document2 pagesObama Declines To Call Armenian Deaths in World War I A ''Genocide''Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Documenting and Debating A Genocide'Document6 pagesDocumenting and Debating A Genocide'Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Armenian Genocide Debate Exposes Rifts at ADLDocument3 pagesArmenian Genocide Debate Exposes Rifts at ADLΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Vinnytsia-The Katyn of Ukraine (A Report From An Eye Witness)Document9 pagesVinnytsia-The Katyn of Ukraine (A Report From An Eye Witness)Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Imagining Orientalism, Ambiguity and InterventionDocument7 pagesImagining Orientalism, Ambiguity and InterventionΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Was Kemel A Freemason?Document5 pagesWas Kemel A Freemason?Καταρα του Χαμ100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hidden HolocaustDocument2 pagesThe Hidden HolocaustΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Pan TurkismDocument10 pagesPan TurkismΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Statistics of Turkey's DemocideDocument9 pagesStatistics of Turkey's DemocideΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Ataturk's ReformsDocument13 pagesAtaturk's ReformsΚαταρα του Χαμ80% (5)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Turkish - Israeli Connection and Its Jewish RootsDocument3 pagesThe Turkish - Israeli Connection and Its Jewish RootsΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Racial Makeup of The TurksDocument5 pagesThe Racial Makeup of The TurksΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- History of The Turkish JewsDocument11 pagesHistory of The Turkish JewsΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Istanbul-Gateway To A Holy WarDocument4 pagesIstanbul-Gateway To A Holy WarΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- When Ataturk Recited Shema Yisrael ''It's My Secret Prayer, Too,'' He ConfessedDocument4 pagesWhen Ataturk Recited Shema Yisrael ''It's My Secret Prayer, Too,'' He ConfessedΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Remembering The Maras Massacre in 1978Document3 pagesRemembering The Maras Massacre in 1978Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Grey Wolves Kill A Peaceful Protestor in Cyprus (1996)Document6 pagesGrey Wolves Kill A Peaceful Protestor in Cyprus (1996)Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Was Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Founder of Modern Turkey, Crypto-Jewish?Document5 pagesWas Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Founder of Modern Turkey, Crypto-Jewish?Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Turkey's Pivotal Role in The International Drug TradeDocument5 pagesTurkey's Pivotal Role in The International Drug TradeΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Scandal Links Turkish Aides To Deaths, Drugs and TerrorDocument4 pagesScandal Links Turkish Aides To Deaths, Drugs and TerrorΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Gray Wolves Spoil Turkey's Publicity Ploy On 'Ararat'Document3 pagesGray Wolves Spoil Turkey's Publicity Ploy On 'Ararat'Καταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Susurluk and The Legacy of Turkey's Dirty WarDocument4 pagesSusurluk and The Legacy of Turkey's Dirty WarΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Turkish Gunman Wants To Be Baptised at The VaticanDocument2 pagesTurkish Gunman Wants To Be Baptised at The VaticanΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Turk Who Shot Pope John Paul II Seeks Polish CitizenshipDocument3 pagesTurk Who Shot Pope John Paul II Seeks Polish CitizenshipΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Papal Assassin Warns Pope Benedict His 'Life Is in Danger' If He Visits TurkeyDocument3 pagesPapal Assassin Warns Pope Benedict His 'Life Is in Danger' If He Visits TurkeyΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- LEONARD RAVENHILL CALLS FOR REVIVAL AND HOLY FIREDocument23 pagesLEONARD RAVENHILL CALLS FOR REVIVAL AND HOLY FIREJim Herwig50% (2)

- Singapore The CountryDocument36 pagesSingapore The CountryAnanya SinhaNo ratings yet

- Ayat-Ayat Ruqyah Plus: Al Fatihah 1-7Document4 pagesAyat-Ayat Ruqyah Plus: Al Fatihah 1-7Vonni Triana Hersa0% (1)

- Jewels of The PauperDocument1 pageJewels of The PauperRainville Love ToseNo ratings yet

- Bible Atlas Manual PDFDocument168 pagesBible Atlas Manual PDFCitac_1100% (1)

- The Reality of HellDocument7 pagesThe Reality of HellThe Fatima CenterNo ratings yet

- Dua For Memorising The QuranDocument2 pagesDua For Memorising The QuranMajidNo ratings yet

- Fusion Reiki Manual by Sherry Andrea PDFDocument6 pagesFusion Reiki Manual by Sherry Andrea PDFKamlesh Mehta100% (1)

- CPAT Reviewer - Law On SalesDocument30 pagesCPAT Reviewer - Law On SalesZaaavnn VannnnnNo ratings yet

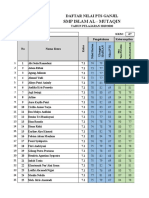

- NILAI PPKN VII Dan VIII MID GANJIL 2019-2020Document37 pagesNILAI PPKN VII Dan VIII MID GANJIL 2019-2020Dheden TrmNo ratings yet

- Notes On J K BaxterDocument4 pagesNotes On J K Baxteraleaf17No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Omam and AicDocument8 pagesOmam and AicDuaa Saqri RamahiNo ratings yet

- Contents of Ramana Jyothi, July 2009Document8 pagesContents of Ramana Jyothi, July 2009Jermaine BeanNo ratings yet

- IBMTE Handbook Chapter 4 Track Changes 2015-2016Document13 pagesIBMTE Handbook Chapter 4 Track Changes 2015-2016Jared Wright (Spectrum Magazine)No ratings yet

- Onlinejyotish 1694202668Document71 pagesOnlinejyotish 1694202668Siri ReddyNo ratings yet

- Christ's Standard of LoveDocument7 pagesChrist's Standard of LoveKaren Hope CalibayNo ratings yet

- Thanks Be To God For His Indescribable GiftDocument2 pagesThanks Be To God For His Indescribable GiftIke AppiahNo ratings yet

- Famous Mahakali Mandir in Chandrapur CityDocument1 pageFamous Mahakali Mandir in Chandrapur Cityvinod kapateNo ratings yet

- Kalki The Next Avatar of God PDFDocument8 pagesKalki The Next Avatar of God PDFmegakiran100% (1)

- RMY 101 Assignment Fall 2020 InstructionsDocument5 pagesRMY 101 Assignment Fall 2020 InstructionsAbass GblaNo ratings yet

- Palm Sunday Hidden Message Word SearchDocument2 pagesPalm Sunday Hidden Message Word SearchЖанна ПищикNo ratings yet

- Migne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 22.Document734 pagesMigne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 22.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- Best, Elsdon - Spiritual and Mental Concepts of The MaoriDocument52 pagesBest, Elsdon - Spiritual and Mental Concepts of The MaoriKüss András100% (2)

- Samuel L. Brengle, The Salvation Army - The Way of Holiness-The Salvation Army (1920) PDFDocument35 pagesSamuel L. Brengle, The Salvation Army - The Way of Holiness-The Salvation Army (1920) PDFFidenceNo ratings yet

- 5 Stages of Grief and Acceptance ProcessDocument19 pages5 Stages of Grief and Acceptance ProcessWendy Veeh Tragico BatarNo ratings yet

- Heroes Imperfectos de Dios Roy Gane (100-143)Document44 pagesHeroes Imperfectos de Dios Roy Gane (100-143)Alvaro Reyes TorresNo ratings yet

- La Monsrtruosa RadioDocument3 pagesLa Monsrtruosa RadioLuciana BarruffaldiNo ratings yet

- 1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 8 Kindergarten Teachers GuideDocument10 pages1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 8 Kindergarten Teachers GuideRitchie FamarinNo ratings yet

- The Spell That Cursed My PeopleDocument3 pagesThe Spell That Cursed My PeopleJulian Williams©™100% (2)

- DEATH The Only Ground For RemarriageDocument7 pagesDEATH The Only Ground For Remarriagemikejeshurun9210No ratings yet