Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mumps and Influenza Compared

Uploaded by

Putri CaesarriniOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mumps and Influenza Compared

Uploaded by

Putri CaesarriniCopyright:

Available Formats

What is swine flu (novel H1N1 influenza A swine flu)?

Swine flu (swine influenza) is a respiratory disease caused by viruses (influenza viruses) that infect the respiratory tract of pigs, resulting in nasal secretions, a barking cough, decreased appetite, and listless behavior. Swine flu produces most of the same symptoms in pigs as human flu produces in people. Swine flu can last about one to two weeks in pigs that survive. Swine influenza virus was first isolated from pigs in 1930 in the U.S. and has been recognized by pork producers and veterinarians to cause infections in pigs worldwide. In a number of instances, people have developed the swine flu infection when they are closely associated with pigs (for example, farmers, pork processors), and likewise, pig populations have occasionally been infected with the human flu infection. In most instances, the cross-species infections (swine virus to man; human flu virus to pigs) have remained in local areas and have not caused national or worldwide infections in either pigs or humans. Unfortunately, this cross-species situation with influenza viruses has had the potential to change. Investigators think the 2009 swine flu strain, first seen in Mexico, should be termed novel H1N1 flu since it is mainly found infecting people and exhibits two main surface antigens, H1 (hemagglutinin type 1) and N1 (neuraminidase type1). Recent investigations show the eight RNA strands from novel H1N1 flu have one strand derived from human flu strains, two from avian (bird) strains, and five from swine strains. Swine flu is transmitted from person to person by inhalation or ingestion of droplets containing virus from people sneezing or coughing; it is not transmitted by eating cooked pork products. What causes swine flu (H1N1)? The cause of swine flu is an influenza A virus type designated as H1N1. It has this designation or name because of the two major antigens (H and N) detectable on its surface by immunological techniques (H or hemagglutinin

and N or neuraminidase). In 2011, a new swine flu virus was detected. The new strain is named influenza A (H3N2)v. Only a few people (mainly children) have been infected, but the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is developing a vaccine against this virus. A separate article discusses some of the details about this new flu strain. In general, all of the influenza A viruses have a structure similar to the H1N1 virus; each type has a somewhat different H and/or N structure.

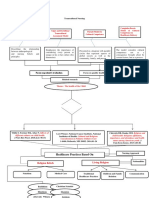

Why is swine flu (H1N1) now infecting humans? Many researchers now consider that two main series of events can lead to swine flu (and also avian or bird flu) becoming a major cause for influenza illness in humans. First, the influenza viruses (types A, B, C) are enveloped RNA viruses with a segmented genome; this means the viral RNA genetic code is not a single strand of RNA but exists as eight different RNA segments in the influenza viruses. A human (or bird) influenza virus can infect a pig respiratory cell at the same time as a swine influenza virus; some of the replicating RNA strands from the human virus can get mistakenly enclosed inside the enveloped swine influenza virus. For example, one cell could contain eight swine flu and eight human flu RNA segments. The total number of RNA types in one cell would be 16; four swine and four human flu RNA segments could be incorporated into one particle, making a viable eight RNA-segmented flu virus from the 16 available segment types. Various combinations of RNA segments can result in a new subtype of virus (this process is known as antigenic shift) that may have the ability to preferentially infect humans but still show characteristics unique to the swine influenza virus (see Figure 1). It is even possible to include RNA strands from birds, swine, and human influenza viruses into one virus if a single cell becomes infected with all three

types of influenza (for example, two bird flu, three swine flu, and three human flu RNA segments to produce a viable eight-segment new type of flu viral genome). Formation of a new viral type is considered to be antigenic shift; small changes within an individual RNA segment in flu viruses are termed antigenic drift and result in minor changes in the virus. However, these can accumulate over time to produce enough minor changes that cumulatively change the virus' antigenic makeup over time (usually years). Second, pigs can play a unique role as an intermediary host to new flu types because pig respiratory cells can be infected directly with bird, human, and other mammalian flu viruses. Consequently, pig respiratory cells are able to be infected with many types of flu and can function as a "mixing pot" for flu RNA segments (see Figure 1). Bird flu viruses, which usually infect the gastrointestinal cells of many bird species, are shed in bird feces. Pigs can pick these viruses up from the environment, and this seems to be the major way that bird flu virus RNA segments enter the mammalian flu virus population.

What are the symptoms of swine flu (H1N1)? Symptoms of swine flu are similar to most influenza infections: fever (100 F or greater), cough, nasal secretions, fatigue, and headache, with fatigue being reported in most infected individuals. Some patients also get nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. In Mexico, many of the initial patients infected with H1N1 influenza were young adults, which made some investigators speculate that a strong immune response, as seen in young people, may cause some collateral tissue damage. Some patients develop severe respiratory symptoms and need respiratory support (such as a ventilator to breathe for the patient). Patients can get pneumonia (bacterial secondary infection) if the viral infection persists, and some can develop seizures. Death often occurs from secondary bacterial

infection of the lungs; appropriate antibiotics need to be used in these patients. The usual mortality (death) rate for typical influenza A is about 0.1%, while the 1918 "Spanish flu" epidemic had an estimated mortality rate ranging from 2%-20%. Swine (H1N1) flu in Mexico had about 160 deaths and about 2,500 confirmed cases, which would correspond to a mortality rate of about 6%, but these initial data have been revised and the mortality rate currently worldwide is estimated to be much lower. By June 2009, the virus had reached 74 different countries on every continent except Antarctica, and by September 2009, the virus had been reported in most countries (over 200) in the world. Fortunately, the mortality rate as of H1N1 has remained low and similar to that of the conventional flu (average conventional flu mortality rate is about 36,000 per year; projected H1N1 flu mortality rate was 90,000 per year in the U.S. as determined by the president's advisory committee, but it never approached that high number). Fortunately, although H1N1 developed into a pandemic (worldwide) flu strain, the mortality rate in the U.S. and many other countries only approximated the usual numbers of flu deaths worldwide. Speculation about why the mortality rate remained much lower than predicted includes increased public awareness and action that produced an increase in hygiene (especially hand washing), a fairly rapid development of a new vaccine, and patient selfisolation if symptoms developed. Research is ongoing to develop data-based answers to such questions.

How is swine flu (H1N1) diagnosed? Swine flu is presumptively diagnosed clinically by the patient's history of association with people known to have the disease and their symptoms listed above. Usually, a quick test (for example, nasopharyngeal swab sample) is done to see if the patient is infected with influenza A or B virus. Most of the

tests can distinguish between A and B types. The test can be negative (no flu infection) or positive for type A and B. If the test is positive for type B, the flu is not likely to be swine flu (H1N1). If it is positive for type A, the person could have a conventional flu strain or swine flu (H1N1). However, the accuracy of these tests has been challenged, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has not completed their comparative studies of these tests. However, a new test developed by the CDC and a commercial company reportedly can detect H1N1 reliably in about one hour; the test was formerly only available to the military. In 2010, the FDA approved a commercially available test that could detect H1N1 within four hours. Most of these rapid tests are based on PCR technology. Swine flu (H1N1) is definitively diagnosed by identifying the particular antigens associated with the virus type. In general, this test is done in a specialized laboratory and is not done by many doctors' offices or hospital laboratories. However, doctors' offices are able to send specimens to specialized laboratories if necessary. Because of the large number of novel H1N1 swine flu cases that occurred in the 2009-2010 flu season (the vast majority of flu cases [about 95%-99%] were due to novel H1N1 flu viruses), the CDC recommended only hospitalized patients' flu virus strains be sent to reference labs to be identified. What treatment is available for swine flu (H1N1)? The best treatment for influenza infections in humans is prevention by vaccination. Work by several laboratories has recently produced vaccines. The first vaccine released in early October 2009 was a nasal spray vaccine that was approved for use in healthy individuals ages 2 through 49. The injectable vaccine, made from killed H1N1, became available in the second week of October 2009. This vaccine was approved for use in ages 6 months to the elderly, including pregnant females. Both of these vaccines were approved by the CDC only after they had conducted clinical trials to prove

that the vaccines were safe and effective. However, caregivers should be aware of the vaccine guidelines that come with the vaccines, as occasionally, the guidelines change. Please see the section below titled "Can novel H1N1 swine flu be prevented with a vaccine?" Almost all vaccines have some side effects. Common side effects of H1N1 vaccines are typical of flu vaccines and are as follows: Flu shot: Soreness, redness, minor swelling at the shot site, muscle aches, low grade fever, and nausea do not usually last more than about 24 hours. Nasal spray: runny nose, low-grade fever, vomiting, headache, wheezing, cough, and sore throat The flu shot is made from killed virus particles so a person cannot get the flu from a flu shot. However, the nasal spray vaccine contains live virus that have been altered to hinder its ability to replicate in human tissue. People with a suppressed immune system should not get vaccinated with the nasal spray. Also, most vaccines that contain flu viral particles are cultivated in eggs, so individuals with an allergy to eggs should not get the vaccine unless tested and advised by their doctor that they are cleared to obtain it. Like all vaccines, rare events may occur in some rare cases (for example, swelling, weakness, or shortness of breath). If any symptoms like these develop, the person should see a physician immediately. Two antiviral agents have been reported to help prevent or reduce the effects of swine flu. They are zanamivir (Relenza) and oseltamivir (Tamiflu), both of which are also used to prevent or reduce influenza A and B symptoms. These drugs should not be used indiscriminately, because viral resistance to them can and has occurred. Also, they are not recommended if the flu symptoms already have been present for 48 hours or more, although hospitalized patients may still be treated past the 48-hour guideline. Severe infections in some patients may require additional supportive measures such as ventilation

support and treatment of other infections like pneumonia that can occur in patients with a severe flu infection. The CDC has suggested in their interim guidelines that pregnant females can be treated with the two antiviral agents.

Pathologic findings in novel influenza A (H1N1) virus ("Swine Flu") infection: contrasting clinical manifestations and lung pathology in two fatal cases.

Although novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection has assumed pandemic proportions, there are few reports of the pathologic findings. Herein we describe the pathologic findings of novel influenza A (H1N1) infection based on findings in 2 autopsy cases. The first patient, a 36-year-old man, had flu-like symptoms; oseltamivir (Tamiflu) therapy was started 8 days after onset of symptoms, and he died on day 15 of his illness. At autopsy, the main finding was diffuse alveolar damage with extensive fresh intra-alveolar hemorrhage. The second patient, a 46year-old woman with alcoholism, was found unresponsive in a basement and brought to the hospital intoxicated and confused. Her condition deteriorated rapidly, and she died 4 days after admission. The main autopsy finding was acute bronchopneumonia with gram-positive cocci, intermixed with diffuse alveolar damage. The pathologic findings in these contrasting cases of novel influenza A (H1N1) infection are similar to those previously described for seasonal influenza. The main pathologic abnormality in fatal cases is diffuse alveolar damage, but it may be overshadowed by an acute bacterial bronchopneumonia.

FROM MAYO CLINIC

Definition

By Mayo Clinic staff The respiratory infection popularly known as swine flu is caused by an influenza virus first recognized in spring 2009, near the end of the usual Northern Hemisphere flu season.

The new virus, 2009 H1N1, spreads quickly and easily. A few months after the first cases were reported, rates of confirmed H1N1-related illness were increasing in almost all parts of the world. As a result, the World Health Organization declared the infection a global pandemic. That official designation remained in place for more than a year.

Technically, the term "swine flu" refers to influenza in pigs. Occasionally, pigs transmit influenza viruses to people, mainly hog farm workers and veterinarians. Less often, someone infected occupationally passes the infection to others. You can't catch swine flu from eating pork.

Causes

By Mayo Clinic staff Influenza viruses infect the cells lining your nose, throat and lungs. The virus enters your body when you inhale contaminated droplets or transfer live virus from a contaminated surface to your eyes, nose or mouth on your hand.

Risk factors

By Mayo Clinic staff If you've traveled to an area where lots of people are affected by swine flu H1N1, you may have been exposed to the virus, particularly if you spent time in large crowds.

Swine farmers and veterinarians have the highest risk of true swine flu because of their exposure to pigs.

Treatments and drugs

By Mayo Clinic staff Most cases of flu, including H1N1 flu, need no treatment other than symptom relief. If you have a chronic respiratory disease, your doctor may prescribe additional medication to decrease inflammation, open your airways and help clear lung secretions.

The antiviral drugs oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) can reduce the severity of symptoms, but flu viruses can develop resistance to them. To make development of resistance less likely and maintain supplies of these drugs for those who need them most, antivirals are reserved for people at high risk of complications.

High-risk groups are those who:

Are hospitalized Have shortness of breath along with other flu symptoms Are younger than 5 years of age Are 65 years and older Are pregnant Are younger than 19 years of age and are receiving long-term aspirin therapy, because of an increased risk for Reye's syndrome

Have certain chronic medical conditions, including asthma, emphysema, heart disease, diabetes, neuromuscular disease, and kidney, liver or blood disease Are immunosuppressed due to medications or HIV

You might also like

- C CCCC CC CCCDocument18 pagesC CCCC CC CCCRichard QuiochoNo ratings yet

- Paper InfluenzaDocument9 pagesPaper InfluenzaPande Indra PremanaNo ratings yet

- Avian Flu, Swine Flu, and Influenza Viruses Explained</TITLEDocument19 pagesAvian Flu, Swine Flu, and Influenza Viruses Explained</TITLEcindraochinNo ratings yet

- Swine Flu Key FactsDocument3 pagesSwine Flu Key Factsctkennedy100% (1)

- Influenza (The Flu) : Ain Shams UniversityDocument53 pagesInfluenza (The Flu) : Ain Shams UniversityfouadNo ratings yet

- Swine FluDocument14 pagesSwine FluGovind PrasadNo ratings yet

- CDC Vs WHODocument7 pagesCDC Vs WHOlistiarsasihNo ratings yet

- In SillicoDocument9 pagesIn Sillicodhruvdesai24No ratings yet

- H1N1 2009: Review Studies and Current Issues Prepared by Arafat Siddiqui Dept. of Pharmacy East-West University Dhaka, BangladeshDocument9 pagesH1N1 2009: Review Studies and Current Issues Prepared by Arafat Siddiqui Dept. of Pharmacy East-West University Dhaka, BangladeshMohammad Arafat SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Swine Flu Research Paper PDFDocument6 pagesSwine Flu Research Paper PDFeghkq0wf100% (1)

- What Is InfluenzaDocument4 pagesWhat Is InfluenzamatorrecNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Influenza VirusDocument108 pagesProject Report On Influenza VirusBrijesh Singh YadavNo ratings yet

- Avian Influenza:: An Internal Report For The College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental SciencesDocument36 pagesAvian Influenza:: An Internal Report For The College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental SciencesBharath ReddyNo ratings yet

- The Bird Flu and YouDocument15 pagesThe Bird Flu and YouMahogony ScottNo ratings yet

- Pandemic Influenza: Types, Subtypes, History and SymptomsDocument24 pagesPandemic Influenza: Types, Subtypes, History and SymptomsQiaoqiao ZhuNo ratings yet

- Spread The Message of Swine Flu To EveryoneDocument3 pagesSpread The Message of Swine Flu To EveryoneDr.Kedar Karki ,M.V.Sc.Preventive Vet.Medicine CLSU PhilippinesNo ratings yet

- AH1N1 PPT PresentationDocument28 pagesAH1N1 PPT PresentationIna Isabela CostiboloNo ratings yet

- 57 PDFDocument6 pages57 PDFJitendra PanthiNo ratings yet

- Symposium Transcript 11 2004Document49 pagesSymposium Transcript 11 2004Mark ReinhardtNo ratings yet

- Fatal Flu (H1N1-H5N1)Document15 pagesFatal Flu (H1N1-H5N1)alaamedNo ratings yet

- World Health Organization - Swine Flu FAQ (April 26, 2009)Document3 pagesWorld Health Organization - Swine Flu FAQ (April 26, 2009)antcomtech100% (9)

- Influenza: Adenoviruses Enteroviruses DengueDocument2 pagesInfluenza: Adenoviruses Enteroviruses DengueAyu NataliaNo ratings yet

- Bird FluDocument5 pagesBird FluNader SmadiNo ratings yet

- Swine Influenza: Nature of The DiseaseDocument8 pagesSwine Influenza: Nature of The Diseasejawairia_mmgNo ratings yet

- Orthomyxoviridae Family of Viruses. Influenza Virus A Includes Only One Species: Influenza A Virus WhichDocument5 pagesOrthomyxoviridae Family of Viruses. Influenza Virus A Includes Only One Species: Influenza A Virus Whichapi-33708392No ratings yet

- Use Various Resources To Find The Answers To The Questions BelowDocument3 pagesUse Various Resources To Find The Answers To The Questions BelowNicole SanchezNo ratings yet

- MS 15-2009 e PrintDocument12 pagesMS 15-2009 e PrinteditorofijtosNo ratings yet

- By Niharika Sharma Prabhakar Kumar Under The Guidance of K.K Ojha (B.H.U)Document17 pagesBy Niharika Sharma Prabhakar Kumar Under The Guidance of K.K Ojha (B.H.U)Prabhakar KumarNo ratings yet

- What Is Influenza?Document9 pagesWhat Is Influenza?Anonymous bYUkftrNo ratings yet

- A (H1N1)Document3 pagesA (H1N1)vincesumergidoNo ratings yet

- Swine FluDocument43 pagesSwine FlupatrikmusicNo ratings yet

- Avian Influenza: Differential Diagnoses & Workup Treatment & Medication Follow-Up MultimediaDocument33 pagesAvian Influenza: Differential Diagnoses & Workup Treatment & Medication Follow-Up MultimedialadywentzNo ratings yet

- Q&A: H1N1 Pandemic Influenza - What's New?: Question & Answer Open AccessDocument6 pagesQ&A: H1N1 Pandemic Influenza - What's New?: Question & Answer Open AccesskarpanaiNo ratings yet

- Swine FluDocument32 pagesSwine FluSajan Varghese100% (1)

- Flu Symptoms, Causes, Prevention and TreatmentDocument6 pagesFlu Symptoms, Causes, Prevention and TreatmentSi VeekeeNo ratings yet

- The Spread, Detection and Causes of Pandemic Influenza: A Seminar PresentedDocument19 pagesThe Spread, Detection and Causes of Pandemic Influenza: A Seminar PresentedMarshal GrahamNo ratings yet

- Swine Influenza ADocument10 pagesSwine Influenza AmaihanyNo ratings yet

- Summary 1: Bird Flu: Avian InfluenzaDocument15 pagesSummary 1: Bird Flu: Avian InfluenzaedrichaNo ratings yet

- Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)Document4 pagesAvian Influenza (Bird Flu)Gia Mae MagdaleraNo ratings yet

- Influenza ReportDocument5 pagesInfluenza ReportwawahalimNo ratings yet

- Health Information: Frequently Asked Questions On Novel Influenza Virus A (H1N1)Document4 pagesHealth Information: Frequently Asked Questions On Novel Influenza Virus A (H1N1)Furqan MirzaNo ratings yet

- Bird FluDocument3 pagesBird FluMd KhanNo ratings yet

- Avian FluDocument19 pagesAvian FluCici Novelia ManurungNo ratings yet

- Swine FluDocument4 pagesSwine Flurgrg rgNo ratings yet

- What Is Avian Influenza?Document3 pagesWhat Is Avian Influenza?Mutia Ainur RahmahNo ratings yet

- InfluenzaVirusInfectionsHumans Jul13Document2 pagesInfluenzaVirusInfectionsHumans Jul13dw_duchNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument20 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptteacherferhdzNo ratings yet

- Swine Flu Pandemic: Cases, Symptoms, PreventionDocument8 pagesSwine Flu Pandemic: Cases, Symptoms, PreventionVehn Marie Dela RosaNo ratings yet

- Cdalert: Special Issue: Human Swine Influenza: A Pandemic ThreatDocument8 pagesCdalert: Special Issue: Human Swine Influenza: A Pandemic ThreatvalentinononNo ratings yet

- Avian Influenza H5N1 Bird Flu: DR Sanjay Shrestha IM Resident, NAMSDocument54 pagesAvian Influenza H5N1 Bird Flu: DR Sanjay Shrestha IM Resident, NAMSSanjay ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Swien InfluenzaDocument2 pagesSwien InfluenzaASHFAQ REHMANINo ratings yet

- Avian PDFDocument11 pagesAvian PDFIzka FadhilahNo ratings yet

- Practice Essentials: H1N1 Influenza (Swine Flu)Document27 pagesPractice Essentials: H1N1 Influenza (Swine Flu)Abdul QuyyumNo ratings yet

- Mi Mi Mi.: Awal Pandemi Influenza A (H1N1) 2009Document2 pagesMi Mi Mi.: Awal Pandemi Influenza A (H1N1) 2009kukuhariawijayaNo ratings yet

- Safari - 3 Nov 2019 22.29 PDFDocument1 pageSafari - 3 Nov 2019 22.29 PDFMuh Ikhlasul AmalNo ratings yet

- What is Flu (Influenza)? Key Facts, Types, and PreventionDocument22 pagesWhat is Flu (Influenza)? Key Facts, Types, and PreventionLeanne TehNo ratings yet

- The Status And UnchangingNames Of The Corona Virus: Why Is It Still Here?From EverandThe Status And UnchangingNames Of The Corona Virus: Why Is It Still Here?No ratings yet

- Framework Nurafni SuidDocument2 pagesFramework Nurafni SuidapninoyNo ratings yet

- Psychological Psychoeducational Neuropsychological Assessment Information For Adults Families 1Document3 pagesPsychological Psychoeducational Neuropsychological Assessment Information For Adults Families 1ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- The So Called Oedematous Skin DiseaseDocument22 pagesThe So Called Oedematous Skin Diseaseمحمد على أحمد أحمدNo ratings yet

- TESTS DISEASES OF BLOOD AND ENDOCRINE SYSTEM Methodical Manual For The 5 Year PDFDocument152 pagesTESTS DISEASES OF BLOOD AND ENDOCRINE SYSTEM Methodical Manual For The 5 Year PDFMayur WakchaureNo ratings yet

- Selective Androgen Receptor ModulatorsDocument7 pagesSelective Androgen Receptor ModulatorsRafael HelenoNo ratings yet

- Review Exercises XiDocument14 pagesReview Exercises XiP. GilbertNo ratings yet

- Surya Namaskar - Searchforlight - Org - Fitness - Suryanamaskar - HTMLDocument4 pagesSurya Namaskar - Searchforlight - Org - Fitness - Suryanamaskar - HTMLmarabunta80No ratings yet

- Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Practice EssentialsDocument28 pagesLower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Practice EssentialsJohnPaulOliverosNo ratings yet

- Sample Employee Stress QuestionnaireDocument1 pageSample Employee Stress Questionnairesanthosh222250% (2)

- Barangay Budget Authorization No. 11Document36 pagesBarangay Budget Authorization No. 11Clarissa PalinesNo ratings yet

- 2019 - Asupan Zat Gizi Makro Dan Mikro Terhadap Kejadian Stunting Pada BalitaDocument6 pages2019 - Asupan Zat Gizi Makro Dan Mikro Terhadap Kejadian Stunting Pada BalitaDemsa SimbolonNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading on Evaluation and Management of Infants Exposed to HIVDocument19 pagesJournal Reading on Evaluation and Management of Infants Exposed to HIVIis Rica MustikaNo ratings yet

- Jejunostomy Feeding Tube Placement in GastrectomyDocument14 pagesJejunostomy Feeding Tube Placement in GastrectomyHarshit UdaiNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2Document6 pagesCase Study 2Princess Pearl MadambaNo ratings yet

- Bone Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and StagingDocument22 pagesBone Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Stagingjinal BhadreshNo ratings yet

- VaanannanDocument53 pagesVaanannankevalNo ratings yet

- Maternal Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein (MSAFP)Document2 pagesMaternal Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein (MSAFP)Shaells JoshiNo ratings yet

- Public Availability of Labeling CBE Guidance PDFDocument6 pagesPublic Availability of Labeling CBE Guidance PDFMichael wangNo ratings yet

- PED011 Final Req 15Document3 pagesPED011 Final Req 15macabalang.yd501No ratings yet

- Coping StrategyDocument2 pagesCoping StrategyJeffson BalmoresNo ratings yet

- PT Behavioral ProblemsDocument11 pagesPT Behavioral ProblemsAmy LalringhluaniNo ratings yet

- Common mental health problems screeningDocument5 pagesCommon mental health problems screeningSaralys MendietaNo ratings yet

- Major Case Presentation On Acute Pulmonary Embolism WithDocument13 pagesMajor Case Presentation On Acute Pulmonary Embolism WithPratibha NatarajNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan: Chronic Pain and COPDDocument11 pagesNursing Care Plan: Chronic Pain and COPDneuronurse100% (1)

- Oral Mucosal Lesions in Children: Upine PublishersDocument3 pagesOral Mucosal Lesions in Children: Upine PublishersbanyubiruNo ratings yet

- TRACTIONDocument3 pagesTRACTIONCatherineNo ratings yet

- Op-Ed ObesityDocument3 pagesOp-Ed Obesityapi-302568521No ratings yet

- Abilify Drug Study: Therapeutic Effects, Indications, Contraindications and Adverse ReactionsDocument6 pagesAbilify Drug Study: Therapeutic Effects, Indications, Contraindications and Adverse ReactionsLuige AvilaNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: Adult Dental Health Survey 2009Document22 pagesExecutive Summary: Adult Dental Health Survey 2009Musaab SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Local Honey Might Help Your AllergiesDocument3 pagesLocal Honey Might Help Your AllergiesDaniel JadeNo ratings yet