Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sample Chapter02

Uploaded by

Shahrzad FazlaliOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sample Chapter02

Uploaded by

Shahrzad FazlaliCopyright:

Available Formats

Anthony Bowrin, VG Sridharan, Farshid Navissi, Udo C.

Braendle,

THE THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

2.1 Agency theory 2.2 Transaction cost economics 2.3 Resource dependence theory 2.4 Stakeholder theory

Learning objectives to describe evolution of theories of corporate governance; to explain the behavior of participants of corporate governance from the point of view of various theories; to conclude on the most critical issues of theories of corporate governance; to explain the role of stakeholders in corporate governance

Key concepts and terms agent principal stakeholder agency costs external control interdependencies asymmetric information moral hazard problem a fair return on investments urgency legitimacy environmental scanning

VG Sridharan, Farshid Navissi

2.1

AGENCY THEORY

1. Introduction 2. Agency Costs and Corporate Governance Solutions 2.1 Origin and development 2.2 Corporate governance solutions 3. Empirical Applications 4. Summary and Conclusions Questions References

1. Introduction Agency theory refers to a set of propositions in governing a modern corporation which is typically characterized by large number of shareholders or owners who allow separate individuals to control and direct the use of their collective capital for future gains. These individuals, typically, may not always own shares but may possess relevant professional skills in managing the corporation. The theory offers many useful ways to examine the relationship between owners and managers and verify how the final objective of maximizing the returns to the owners is achieved, particularly when the managers do not own the corporations resources. Following Adam Smith (1776), Berle and Means (1932) initiate the discussion relating to the concerns of separation of ownership and control in a large corporation. However, the concerns are aggregated by Jensen and Meckling (1976) into the agency problem in governing the corporation. Jensen and Meckling identify managers as the agents who are employed to work for maximizing the returns to the shareholders, who are the principals. Jensen and Meckling assume that as agents do not own the corporations resources, they may commit moral hazards (such as shirking duties to enjoy leisure and hiding inefficiency to

avoid loss of rewards) merely to enhance their own personal wealth at the cost of their principals. To minimize the potential for such agency problems, Jensen (1983) recognizes two important steps: first, the principal-agent risk-bearing mechanism must be designed efficiently and second, the design must be monitored through the nexus of organizations and contracts. The first step, considered as the formal agency literature, examines how much of risks should each party assume in return for their respective gains. The principal must transfer some rights to the agent who, in turn, must accept to carry out the duties enshrined in the rights. The second step, which Jensen (1983, p. 334) identifies as the positive agency theory, clarifies how firms use contractual monitoring and bonding to bear upon the structure designed in the first step and derive potential solutions to the agency problems. The inevitable loss of firm value that arises with the agency problems along with the costs of contractual monitoring and bonding are defined as agency costs (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Several empirical studies have since adopted agency theory to identify solutions to specific contexts such as diversification strategies within firms (e.g., Kehoe, 1996; and Denis, Denis and Sarin, 1999). We relate the theory in a more generic sense of corporate governance. Keasey and Wright (1993) define corporate governance in terms of structures, process, cultures and systems that engender the successful operation of organizations. 2. Agency Costs and Corporate Governance Solutions 2.1 Origin and development Adam Smiths (1776) Wealth of Nations is perhaps the major driving force for several modern economists to develop new aspects of organizational theory. Among other things, Smith predicts that if an economic firm is controlled by a person or group of persons other than the firms owners, the objectives of the owners are more likely to be diluted than ideally fulfilled. Berle and Means (1932) consider Smiths (1776) concern to specifically examine the organizational and public policy ramifications of ownership and control separation in large firms. They argue that as ownership gets increasingly held by different individuals, the industry becomes consolidated and hence the checks to limit the use of power tend to disappear (McCraw, 1990, p. 582). Jensen and Meckling (1976) develop the concern of ownership-control separation into a fully fledged agency problem comprised within the economic theory of the firm. In their paper, Jensen and Meckling identify the costs of the agency problem and trace who bears the costs and why. Managers may commit moral hazards merely to enhance their own personal wealth at the cost of shareholders

EXHIBIT 2.1 The Berle and Means corporate revolution In 1929, Means found that in only 11% of the 200 largest non-financial corporations the largest owner hold a majority of the firms shares. Further, establishing ownership of 20% of the stock as a threshold minimum for control, 44% of those firms had no individual who owned that much of the stock. These 88 firms which were classified as management-controlled also managed to account for 58% of the total assets held among the top 200 corporations. Two trends were indicated: the growing concentration of power and the increasing dispersal of stock ownership resulting in a widening gulf between share ownership and executive control within large corporations. Berle and Means were persuaded that the corporate revolution occurred.

Source: Berle and Means, 1932

Agency costs are described as follows. Assuming that the principal and the agent are mainly concerned about maximizing their personal wealth, agency theory believes that the agent may not always act in the best interests of the principal. Added to this, long term contingencies are also not amenable to be predicted, which makes the principal build only incomplete contracts with the agent. Note that incomplete contracting set up makes the study of agency relationship critical. The principal needs to set appropriate incentives for the agent and also establish monitoring mechanisms to control any deviant activities of the agent, which are classified as the monitoring costs. Jensen and Meckling (1976, p. 311) clarify that the term monitoring is comprehensive as it includes controls, such as setting budget restrictions and operating rules, beyond merely observing and measuring the agents performance. Further, the agent may also spend resources in guaranteeing that he or she would not take actions which would harm the principal (an example is the bond provided by the agent) which is included under bonding costs. Even after incurring monitoring and bonding costs, the principal may suffer loss since the agents decisions may be different to those that would maximize the principals welfare. The monetary equivalent of such loss is classified as the residual loss. In summary, agency costs are the total of 1) monitoring costs, 2) bonding costs and 3) residual loss. Williamson (1988) further clarifies that residual loss is the key cost that the principal would seek to reduce. To help achieve this objective, the principal incurs monitoring costs and makes the agent incur bonding costs. Hence, the irreducible agency costs are the minimum of these three costs. Prior to examining the wealth effects of these agency costs, Jensen and Meckling clarify that they do not look into the normative aspect of how to structure an optimal contract between the parties but only the positive aspect of the incentives of the principal and the agent to enter into a contractual relationship, given the circumstances under which the contract is designed. Agency costs are the total of monitoring costs, bonding costs and residual loss

Typically, ownership and control get separated whenever a firms owner dilutes his ownership rights by selling a small portion of the firm to new buyers. This may be because the owner may like to gain better utility (either pecuniary or non-pecuniary) by dispensing some of his or her ownership rights. The new owners do not hold a controlling interest in the firm which is still held by the old owner. Note here that the old owner continues to run the firm as an agent to protect the interests of the new owners who are the principals. Expecting a divergence of interests with the old owner, the new owners may believe that the old owners decisions may need to be monitored. A practical way for the new owners is to deduct potential monitoring costs from the purchase price payable to the old owner. Often called pricing-out strategy, such net payments reduce the wealth of the old owner. In addition, the old owner may also need to spend moneys on bonding to offer guarantees to the new owners. In short, the agency costs or the wealth-effects of the separation of ownership and control are borne by the old owner-and-controller, who has all the incentives to ensure that the agency costs are kept at a minimum level. The same explanation can be extended to even a situation where an owner sells the entire firm to a number of buyers but continues to run the firm merely as a manager, along with other professional managers. The buyers (hereafter, the new owners) and the managers hold specialized experience and skills in financing and managing, respectively. This is an important reason for the existence of large modern corporations. The new owners contract to pay the managers risks of acquiring firm-specific knowledge and experience whose value is more within the firm and less elsewhere. The managers agree to compensate the new owners for potential contractual defaults. However, Jensen and Meckling (1976) believe that the degree to which the original owner may dilute his or her ownership status depends upon factors such as the amount of monitoring and bonding costs associated with the separation and the owners aptitudes and interests in relation to controlling totally-owned as against partially-owned resources. 2.2 Corporate governance solutions Though Jensen and Meckling (1976) mention the important role of monitoring in an agency relationship, they do not examine further how a large firm achieves efficient monitoring. In other words, how do firms structure their corporate governance in order to control the agency problem created by the separation of ownership and control? Fama (1980) pursues this concern and finds that the agency problem is controlled efficiently by a large firm through internal devices established in response to competition from other firms. Further, Fama (1980, p. 288) claims that individual managers within the firm are controlled by the markets discipline and opportunities for their services both within and outside the firm. The deAgency problem is controlled efficiently by a large firm through internal devices established in response to competition from other firms

vices referred to in Fama (1980) is examined in greater detail in Fama and Jensen (1983, pp. 303-304). Fama and Jensen argue that firms typically segregate decision management from the decision control rights both at top (the board and managers) and lower levels (managers and workers) of the firms hierarchy. In a broad sense, decision management relate to carrying out a firms function while decision control relates to overseeing the performance of the decision management function. Decision management rights cover two rights: initiation and execution. Decision control includes two rights of approval and evaluation. Initiation refers to generating proposals for investing a firms resources and structuring contracts. In this right, decisions on whether to accept a particular customer order and plans on how to conduct the transaction internally are taken. Approval the second right relates to the choice of a proposal and the contract. Execution, the next right refers to physically carrying out the chosen proposal and Evaluation, the last right refers to overseeing the progress of execution and assessing how all other rights were exercised. The reason for why Fama and Jensen (1983) distinguish decision management from decision control is to avoid situations where the agent, with no ownership of firms resources, may enhance self-interest by decisions that are suboptimal to the principal. The board of directors is appointed by the owners as a corporate governance solution to control the agency problem likely to arise with the senior managers including the CEO. The board holds the decision control authority while the senior managers hold the decision management rights. The constitution and compensation of the board can also be explained in agency terms. The appointment of outside directors is to ensure objectivity to other internal directors decisions. In order that that a director carries out his or her duties diligently, the owners offer share-based incentives such as stock grants or options. The expectation is that such incentive contracts can align the interests of directors and owners and thus help mitigate agency problems. The market discipline ensures that a firms corporate governance is fair. For instance, if a firm suffers due to its boards failure to exercise fiduciary duties diligently, the firm may likely be acquired or taken over by a competitor firm whose owners believe that they can reduce the agency costs of the ailing firm. Similarly, management control systems within a firm are also designed to ensure that managers oversee (decision control) the tasks carried out (decision management) by workers. One exception to the segregation of decision management from decision control is when the decision-maker is also the owner or a major residual claimant. In such a case, there is no conflict of interest because the owner owns the resources of the firm. The segregation of decision management and control is similar to Stettlers (1977) comment in the auditing literature that operational and accounting duties be separated.

The constitution and compensation of the board can also be explained in agency terms

3. Empirical Applications Several studies validate agency theory predictions in different contexts. For instance, firms public offer of new capital (Denis, Denis and Sarin, 1999), franchisee set up (Kehoe, 1996), technology strategy in the process of new product development (Krishnan and Loch, 2005), and labor union transactions are among a few such contexts that apply agency theoretic framework. Denis et al. (1999) state the reasons for why a firms diversification strategy is likely to reduce firm value. They find that diversified firms trade at a discount as against their single-segment peers and further prior studies find significant positive relation between greater shareholder wealth and focused strategy for many leading US firms. Given that diversification can lead to value reduction, Denis et al. (1999) examine why managers resort to corporate diversifications. They argue that managers do so as their private benefits (pecuniary such as incentives and non-pecuniary such as power) related with diversified portfolio. Kehoe (1996) finds that franchisee set up is considered efficient to minimize agency problems of shirking. Franchisees are compensated from the residual claims of their individual units. Therefore, they tend to bear most or all of the costs of shirking. In conclusion, while there is a large empirical support for agency theory, new studies examine if the theory holds good for newer variants of organizational structures. Further, new studies also analyze how agency theory holds as against other theories. For instance, Denis et al. (1999) find that corporate diversifications are examined with strategic management-led stewardship theory as against the organizational economics-led agency theory. 4. Summary and Conclusions Agency theory is an important set of propositions in the organizational economics discipline. The theory is founded under the assumption that when ownership is separated from the control of a large firm, the manager acting as an agent on behalf of the owner-principal is prone to creating moral hazards such as shirking and seizing wealth at the expense of the principal. Hence, the theory suggests that the principal builds appropriate ex ante incentive mechanisms to deter the agent from indulging in such behavior. The incentive mechanisms include monitoring by the principal and bonding by the agent. However, the cost of these mechanisms is usually borne by the agent because the principal implicitly prices-out the monitoring costs to the agent. Monitoring is undertaken by separating decision control and decision management at all levels in a firms hierarchy.

Questions

Describe the assumptions underlying agency theory. What is an agency problem? Explain why it is particularly important to analyze this problem in large publicly-held organizations? Explain the term agency costs. Examine the role and features of agency costs in relation to an agency contract. Discuss the potential solutions for a contract having high agency costs.

References

1. Denis, D.J., D.K. Denis and A. Sarin (1999) Agency Theory and the Influence of Equity Ownership Structure on Corporate Diversification Strategies Strategic Management Journal, V.20, 11, pp. 1071-1076. 2. Fama, E.F., (1980) Agency Problems and the Theory of the Firm The Journal of Political Economy, V.88, 2, pp. 288-307. 3. Fama, E.F., and M.C. Jensen (1983), Separation of Ownership and Control, Journal of Law and Economics, V.26, 2, pp. 301-325. 4. Keasey, K. and M. Wright (1993). Issues in corporate accountability and governance: An editorial Accounting and Business Research, 23(91A): 291303. 5. Jensen, M.C., (1983) Organization Theory and Methodology The Accounting Review, V.LVIII, 2, pp. 319-339. 6. Jensen, M.C., and W.H. Meckling (1976) Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure Journal of Financial Economics, October, V.3, 4, pp. 305-360. 7. Kehoe, M.R., (1996) Franchising, Agency Problems, and the Cost of Capital Applied Economics, 28, pp. 1485-1493. 8. Krishnan, V., and C.H. Loch (2005) A Retrospective Look at Production and Operations Management Articles on New Product Development Production and Operations Management, V.14, 4, pp. 433-441. 9. McCraw, T.K., (1990), In Retrospect: Berle and Means Reviews in American History, V.18, 4, pp. 578-596. 10. Smith, A., (1776) The Wealth of Nations. Edited by Edwin Cannan, 1904. Reprint edition, 1937. New York, Modern Library. 11. Stettler, H.P., (1977), Auditing Principles, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall. 12. Williamson, O.E (1988) Corporate Finance and Corporate Governance, Journal of Finance, 43, pp. 567-591.

You might also like

- Corporate Finance for CFA level 1: CFA level 1, #1From EverandCorporate Finance for CFA level 1: CFA level 1, #1Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- JENSEN AND MECKLING A Summary PDFDocument6 pagesJENSEN AND MECKLING A Summary PDFponchoNo ratings yet

- Fiancial Management AssignmentDocument5 pagesFiancial Management Assignmentbelete ephremNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review of Agency TheoryDocument2 pagesA Literature Review of Agency TheoryRickie FebriadyNo ratings yet

- Agency Theory - UKDocument77 pagesAgency Theory - UKjames100% (6)

- A Literature Review of Agency TheoryDocument2 pagesA Literature Review of Agency TheoryNcu'mmy Gisly'KayinganaNo ratings yet

- Agency Costs Impact on Capital StructureDocument12 pagesAgency Costs Impact on Capital StructureHoàng Anh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Brigham & Gapenski, 2009Document8 pagesBrigham & Gapenski, 2009Leny_PINo ratings yet

- Capital Structure and Ownership Structure: A Review of LiteratureDocument8 pagesCapital Structure and Ownership Structure: A Review of LiteratureshadulyNo ratings yet

- Agency Theory - PresentationDocument14 pagesAgency Theory - PresentationSaeed AhmadNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance and Firm Performance: Theory and Evidence From LiteratureDocument29 pagesCorporate Governance and Firm Performance: Theory and Evidence From LiteratureShafqat BukhariNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Corporate Governance in Taiwan: Trends and RecommendationsDocument28 pagesCase Study of Corporate Governance in Taiwan: Trends and RecommendationsdwijaluNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Corporate Governance in Taiwan: Trends and RecommendationsDocument29 pagesCase Study of Corporate Governance in Taiwan: Trends and RecommendationsariaNo ratings yet

- 5 Chapter-1Document19 pages5 Chapter-1rehan100% (1)

- 313 AssignmentDocument5 pages313 AssignmentMicahNo ratings yet

- Agency Problem and The Role of Corporate GovernanceDocument19 pagesAgency Problem and The Role of Corporate GovernanceIan Try Putranto86% (22)

- Theorizing CGDocument28 pagesTheorizing CGjjoeNo ratings yet

- 2001 - DK Denis - Twenty-Five Years of Corporate Governance Research and CountingDocument22 pages2001 - DK Denis - Twenty-Five Years of Corporate Governance Research and Countingahmed sharkasNo ratings yet

- Hill & Jones 1992Document25 pagesHill & Jones 1992LEO GAONo ratings yet

- The Theoretical Framework For Corporate GovernanceDocument21 pagesThe Theoretical Framework For Corporate GovernanceomarelzainNo ratings yet

- Agency Costs and Shareholder-Manager ConflictsDocument14 pagesAgency Costs and Shareholder-Manager Conflictsహరీష్ చింతలపూడిNo ratings yet

- Agency Theory Is About The Conflicts That Arise Between The PrincipalDocument9 pagesAgency Theory Is About The Conflicts That Arise Between The PrincipalMarlvern Panashe ZifambaNo ratings yet

- Agency TheoryDocument7 pagesAgency Theoryhakam karimNo ratings yet

- Agency TheoryDocument18 pagesAgency TheorySimon MutekeNo ratings yet

- Defining Corporate Governance Report SourcesDocument4 pagesDefining Corporate Governance Report SourcesJeff CadavaNo ratings yet

- Reall Work ThesisDocument30 pagesReall Work ThesisgetachewNo ratings yet

- Jensen and Meckling (1976)Document22 pagesJensen and Meckling (1976)Taufik IsmailNo ratings yet

- Theory of The Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership StructureDocument78 pagesTheory of The Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership StructureCesar OliveraNo ratings yet

- Executive Incentives ResitDocument8 pagesExecutive Incentives ResitWerchampiomsNo ratings yet

- EAI210082Document23 pagesEAI210082Kavitha LayaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Debt in Reducing Agency Cost Empirical Evidence From PakistanDocument16 pagesThe Role of Debt in Reducing Agency Cost Empirical Evidence From PakistanvioalessaNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Agency TheoryDocument24 pagesStakeholder Agency TheoryLaura ArdilaNo ratings yet

- Twenty-Five Years of Corporate Governance Research - . - and CountingDocument22 pagesTwenty-Five Years of Corporate Governance Research - . - and CountingLareb ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Effects of Agency Problems on Firms' Value: A Survey of Listed Companies in NakuruDocument31 pagesEffects of Agency Problems on Firms' Value: A Survey of Listed Companies in NakuruAmy SyahidaNo ratings yet

- Defining Corporate Governance: Shareholder Versus Stakeholder ModelsDocument16 pagesDefining Corporate Governance: Shareholder Versus Stakeholder ModelsPratibha LakraNo ratings yet

- Agency Problem AssignmentDocument18 pagesAgency Problem Assignmentjames94% (31)

- Agency Theory ExplainedDocument11 pagesAgency Theory ExplainedMuhammad HarisNo ratings yet

- Content: Acknowledge List of Abbreviations List of TablesDocument33 pagesContent: Acknowledge List of Abbreviations List of TablesNguyễn Hoàng TríNo ratings yet

- Lecture 03 CG TheoriesDocument37 pagesLecture 03 CG TheoriesWILBROAD THEOBARDNo ratings yet

- Agency Theory Suggests That The Firm Can Be Viewed As A Nexus of ContractsDocument5 pagesAgency Theory Suggests That The Firm Can Be Viewed As A Nexus of ContractsMilan RathodNo ratings yet

- Theory of the Firm - Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure-1-40Document40 pagesTheory of the Firm - Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure-1-40mutia.wNo ratings yet

- Corporate Ownership Firm Financing Choices and Firm Value Evidenced From Emerging Markets, PakistanDocument19 pagesCorporate Ownership Firm Financing Choices and Firm Value Evidenced From Emerging Markets, PakistanEncenggNo ratings yet

- Cost Transaction Agency TheoryDocument2 pagesCost Transaction Agency Theoryihsan hassouneNo ratings yet

- What is Agency Theory? Conflicts and CostsDocument12 pagesWhat is Agency Theory? Conflicts and CostsAjeesh MkNo ratings yet

- Political Science Economics Asymmetric Information Principal AgentDocument7 pagesPolitical Science Economics Asymmetric Information Principal AgentPrashant RampuriaNo ratings yet

- Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership StructureDocument55 pagesTheory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership StructureBara HakikiNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance in InsuranceDocument95 pagesCorporate Governance in Insurancemohyeb50% (4)

- Agency Theory in Corporate Governance ExplainedDocument8 pagesAgency Theory in Corporate Governance ExplainedNOLI TAMBAOANNo ratings yet

- Review of Major Capital Structure TheoriesDocument3 pagesReview of Major Capital Structure TheoriesMalik Usman AhmadNo ratings yet

- Assignmen 1Document8 pagesAssignmen 1Justice DzamaNo ratings yet

- Agency Costs of Cash Flow - MC JensenDocument15 pagesAgency Costs of Cash Flow - MC JensentakerNo ratings yet

- FIN301 Managerial Finance - Honors Program: Agency Problem (Cost) 1Document14 pagesFIN301 Managerial Finance - Honors Program: Agency Problem (Cost) 1cynthiaNo ratings yet

- Principles of corporate governanceDocument6 pagesPrinciples of corporate governanceTrần Ánh NgọcNo ratings yet

- Corporate GovernanceDocument20 pagesCorporate GovernanceSyed Israr HussainNo ratings yet

- Agency Theory Summary Delves PatrickDocument11 pagesAgency Theory Summary Delves PatrickDavid OkombaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Capital Structure On Firms' Profitability (Evidenced From Ethiopian) PDFDocument9 pagesThe Effect of Capital Structure On Firms' Profitability (Evidenced From Ethiopian) PDFKulsoomNo ratings yet

- Corporate Finance: A Beginner's Guide: Investment series, #1From EverandCorporate Finance: A Beginner's Guide: Investment series, #1No ratings yet

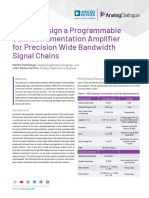

- (App Note) How To Design A Programmable Gain Instrumentation AmplifierDocument7 pages(App Note) How To Design A Programmable Gain Instrumentation AmplifierIoan TudosaNo ratings yet

- Av1 OnDocument7 pagesAv1 OnLê Hà Thanh TrúcNo ratings yet

- What Is Rack Chock SystemDocument7 pagesWhat Is Rack Chock SystemSarah Perez100% (1)

- SQL 1: Basic Statements: Yufei TaoDocument24 pagesSQL 1: Basic Statements: Yufei TaoHui Ka HoNo ratings yet

- AP Euro Unit 2 Study GuideDocument11 pagesAP Euro Unit 2 Study GuideexmordisNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Towards AppleDocument47 pagesConsumer Behaviour Towards AppleAdnan Yusufzai69% (62)

- Indian Institute OF Management, BangaloreDocument20 pagesIndian Institute OF Management, BangaloreGagandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Obsolescence 2. Book Value 3. Depreciation 4. Depletion EtcDocument9 pagesObsolescence 2. Book Value 3. Depreciation 4. Depletion EtcKHAN AQSANo ratings yet

- Center of Gravity and Shear Center of Thin-Walled Open-Section Composite BeamsDocument6 pagesCenter of Gravity and Shear Center of Thin-Walled Open-Section Composite Beamsredz00100% (1)

- Module 4-Answer KeyDocument100 pagesModule 4-Answer KeyAna Marie Suganob82% (22)

- Lab ReportDocument5 pagesLab ReportHugsNo ratings yet

- IEC-60721-3-3-2019 (Enviromental Conditions)Document12 pagesIEC-60721-3-3-2019 (Enviromental Conditions)Electrical DistributionNo ratings yet

- Compare and Contrast High School and College EssayDocument6 pagesCompare and Contrast High School and College Essayafibkyielxfbab100% (1)

- Health Information System Developmen T (Medical Records)Document21 pagesHealth Information System Developmen T (Medical Records)skidz137217100% (10)

- Wsi PSDDocument18 pagesWsi PSDДрагиша Небитни ТрифуновићNo ratings yet

- Zhihua Yao - Dignaga and The 4 Types of Perception (JIP 04)Document24 pagesZhihua Yao - Dignaga and The 4 Types of Perception (JIP 04)Carlos Caicedo-Russi100% (1)

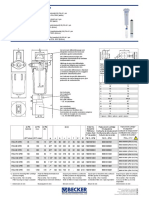

- Medical filter performance specificationsDocument1 pageMedical filter performance specificationsPT.Intidaya Dinamika SejatiNo ratings yet

- 2.0 - SITHKOP002 - Plan and Cost Basic Menus Student GuideDocument92 pages2.0 - SITHKOP002 - Plan and Cost Basic Menus Student Guidebash qwertNo ratings yet

- Hotel and Restaurant at Blue Nile FallsDocument26 pagesHotel and Restaurant at Blue Nile Fallsbig johnNo ratings yet

- Crash Cart - General Checklist For Medical Supplies On Crash CartsDocument3 pagesCrash Cart - General Checklist For Medical Supplies On Crash CartsYassen ManiriNo ratings yet

- 4 - Complex IntegralsDocument89 pages4 - Complex IntegralsryuzackyNo ratings yet

- LAC-Documentation-Tool Session 2Document4 pagesLAC-Documentation-Tool Session 2DenMark Tuazon-RañolaNo ratings yet

- STERNOL Specification ToolDocument15 pagesSTERNOL Specification ToolMahdyZargarNo ratings yet

- R4 User GuideDocument48 pagesR4 User GuideAaron SmithNo ratings yet

- E-banking and transaction conceptsDocument17 pagesE-banking and transaction conceptssumedh narwadeNo ratings yet

- Choose the Best WordDocument7 pagesChoose the Best WordJohnny JohnnieeNo ratings yet

- Turbine 1st Stage Nozzle - DPTDocument15 pagesTurbine 1st Stage Nozzle - DPTAnonymous gWKgdUBNo ratings yet

- No.6 Role-Of-Child-Health-NurseDocument8 pagesNo.6 Role-Of-Child-Health-NursePawan BatthNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - IntroductionDocument42 pagesChapter 1 - IntroductionShola ayipNo ratings yet

- Masonry Brickwork 230 MMDocument1 pageMasonry Brickwork 230 MMrohanNo ratings yet