Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Co - 5799 - 2012 Russell Gray's Witness Statement

Uploaded by

BermondseyVillageAGOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

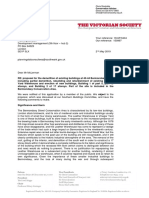

Available Formats

Co - 5799 - 2012 Russell Gray's Witness Statement

Uploaded by

BermondseyVillageAGCopyright:

Available Formats

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEENS BENCH DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE COURT

CLAIM NO CO/5799/2012

IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION FOR PERMISSION TO CLAIM JUDICIAL REVIEW

BETWEEN: THE QUEEN

on the application of

RUSSELL GRAY as representative Claimant on behalf of BERMONDSEY VILLAGE ACTION GROUP (BVAG)

Claimant

and

(1) LONDON BOROUGH OF SOUTHWARK (2) THE MAYOR OF LONDON (3)THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT (4) HISTORIC BUILDINGS AND MONUMENTS COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND

Defendants and

(1) NETWORK RAIL (2) DEPARTMENT FOR TRANSPORT

Interested Parties

WITNESS STATEMENT OF THE CLAIMANT

Format (1) This statement is presented in two sections. First it comprises a broadly chronological narrative of the events from pre-application discussions to the issue of the planning consents we challenge. In the second section I draw on documents obtained under freedom of information laws that were not available to us until more recently (and which are still somewhat lacking) to corroborate and substantiate our perception of events that was initially a product of reasoned analysis rather than documentary evidence. The consideration of disclosed documents is divided into sections dealing with the roles of the different authorities and potentially (by way of supplement) the collective approaches taken to each of the different heritage assets we believe have been improperly authorised for demolition. By this division of the statement into different threads I have aimed to make it easier to illuminate the specific roles of the various parties. This approach necessitates some repetition where certain events fall within different narrative threads. BVAG background (2) I have worked in the area south of London Bridge and Tower Bridge, now designated Bermondsey Village by Southwark Council, for the past 20 years. I have also lived mostly in the same area since 1987. My Company, Shiva Ltd, owns and operates a substantial site in Bermondsey St that comprises a collection of restored Victorian industrial buildings now occupied by companies engaged in the creative industries. The buildings were derelict when we acquired them and in the process of their restoration I have become familiar with traditional building methods and craftsmanship and experienced in preservation of the fabric of historic buildings in refurbishment projects. (3) BVAG was born out of an initial public meeting that I called to raise awareness among local people of how planning policy for the area was being formulated with scant regard to them. It has since focused on trying to influence policy towards preservation of the character of the area immediately around London Bridge Station and to the South of it. 2

London Bridge Station (4) BVAGs first involvement specifically with London Bridge Station heritage came in October 2010, following a meeting we hosted with Malcolm Woods, Area Adviser of English Heritage. Following that meeting one of our members did some historical research and produced information to support an application to English Heritage for listing of the arcade fronting the railway viaduct in St Thomas St and Crucifix Lane. This ornate brick arcade merges into the double-height arched wall of the train shed, where the incoming London Bridge railway lines terminate. Our request for listing followed a suggestion from Mr Woods that we ask English Heritage to remove the ambiguity as to where the already listed train shed met the then unlisted but integral incoming viaduct arches. He had put that suggestion in writing the day after our meeting (exhibit E.1). The ambiguity of the demarcation of the trainshed wall from the arcade is significant because English Heritage later resolve to overlook it. (5) The arches were eventually listed in July 2011 pursuant to the recommendation of English Heritage (exhibit E.2). However, some while before this we received a copy of a report that Network Rail had commissioned CgMs consultants to prepare making a case against listing of the arches (exhibit E.3). This report caused some consternation in our group as it adopted a condescending tone of independence and objectivity. Furthermore, in commissioning it Network Rail had bypassed their own in-house sponsored but semi-independent heritage adviser, Andy Savage, (aka The Railway Heritage Trust) who was highly embarrassed at being short circuited. The author of the CgMs report was Edward Kitchen. Although we did not know it at the time, Mr Kitchen was already in discussions with Southwark planners on behalf of Network Rail about extensive demolition of heritage at London Bridge to include part of the St Thomas St. arcade itself. (6) There was a lengthy delay between our application to English Heritage to list the arches and their recommendation to DCMS to do so. At the time of writing this statement English Heritage are refusing our EIR request for disclosure of internal documents relating to all elements of the London Bridge heritage under threat on the grounds that the request is manifestly unreasonable. Documents that might 3

explain the delay therefore may be forthcoming in due course. What is obvious that whilst English Heritage were considering our application for listing of the arcade they were simultaneously agreeing demolition of part of it, and its continuation, the trainshed wall, with Network Rail. (7) BVAG became the focus of local opposition to the heritage destruction entailed in Network Rails present proposals for redevelopment of London Bridge station. The heritage under threat Grade II listed train Shed (1864-7) and associated arches (1864-6) by Charles Henry Driver (exhibit I.1) (8) Charles Driver is best known for his work on the great London Victorian sewer project under Joseph Bazalgette particularly the pumping stations at Abbey Mills and Crossness. He also worked extensively on the other great infrastructural project of his era, the railways. He was a champion and an early master of the use of cast iron in architecture. (9) The train shed and arches at London Bridge have to be viewed to some extent in terms of their different components. The southern flank wall of the shed in St Thomas St is part of a continuous, elaborately arcaded, brick structure that embraces the arches fronting the viaduct carrying the terminating lines originally built by the London Brighton and South Coast, and latterly Southern, Railway. In the double height section carrying the shed roof the arches at the upper level are all blind and at ground floor level they are open. The single tier arches extend out to the east along St Thomas St and Crucifix Lane and are all open, providing ornate entrances to a labyrinthine series of abutting viaducts that are the result of successive widenings of the original 1836 London & Greenwich line. (10) The shed roof is comprised of a central crescent component of wrought iron trusses supported on 24 distinctive (Driver-style) cast iron columns and spandrels. There are two flat roof flanks carried on riveted lattice beams, extending the roofed area out to the southern and northern flank walls. The question of the legitimacy of 4

the conceptual and practical separation of the various components of the shed and arches and the ironwork of the roof is central to BVAGs challenge to the justification advanced by Network Rail for its extensive proposed demolitions and the planning authorities attempts to bring it within the scope of policy on demolition of heritage assets. The South Eastern Railway Offices (1897-1900) by Charles Barry Junior (exhibit I.2, I.3) (11) The South Eastern Railway Offices (SERO) on Tooley St is believed to be the last building by Charles Barry junior, who is best known for his work in Dulwich, particularly Dulwich College School. (12) The SERO is in a conservation area and recognized as making an important contribution to the area. This designation accords it similar protection to listed buildings but gives developers slightly more leeway in how it may be treated. Once it became known that Network Rail were seeking permission to demolish the building, the Victorian Society made an application to English Heritage to list it. Their listing application was submitted to EH on 13 June 2011. English Heritage recommended to DCMS that the building should not be listed and on 25 July wrote to the Vic Soc. Reporting the DCMSs acceptance of their recommendation. The Victorian Society, with some new information on the building, then sought a review of the EH advice on 19 August 2011. On 15 December DCMS notified us that EH had reaffirmed their position. Curiously, the EH review (exhibit E.4) was signed off by the senior designation adviser concerned, Delcia Keate, on 11 October. Early this year BVAG presented further new evidence on matters not considered by EH in reaching their (non-) listing recommendation and requested a further review. Again, we were notified by DCMS that EH would not revise their recommendation. (13) The obvious quality of the SERO building as compared with other buildings by Barry junior (almost all of which are listed) together with EHs refusal to recommend listing has angered and frustrated heritage organisations and interested individuals. The general perception is that English Heritage did not act impartially in evaluating

the SERO and were under pressure not to frustrate Network Rails plans for demolition of the building. London Bridge proposals (14) I do not remember precisely when the present redevelopment proposals came to my attention, probably because of the long history of abortive plans going back some 15 years and because early notice came only in the form of disparate sketchy local rumours. These included the suggestions that the project was in stop-go limbo because there was an issue over availability of Government funding for the project and that the train shed roof was to be dismantled and fully restored off-site for reassembly as part of the reconfigured station. (15) I believe that a definitive go-ahead for the project was given by central government at some time in 2010 and by early 2011 the proposals were beginning to be talked about with greater certainty. By February 2011 Network Rail were doing some sketchy presentations on their proposals. The first I attended was on 17 March with the local Chamber of Commerce who hosted an open lunch at which Chris Drabble of Network Rail presented some slides and gave an effusive but very general explanation of the scheme. My questions to Mr Drabble after his presentation focused on the seemingly insensitive approach to the Victorian heritage of the station often cited as the worlds oldest city-centre railway terminus. (16) At the time I dont think it was clear that the plans involved the demolition of the SERO. It was however clear that NR proposed to demolish the southern flank wall of the train shed to create a new entrance in St Thomas St. As the building is listed and since the flank wall comprises a whole arcade of arches at ground level, the obvious question was why the arches were not simply being used to provide the entrances required for the new concourse. (exhibit I.3, I.4) Mr Drabbles response was the memorable first warning that Network Rail was not going to play by the book. He maintained, with unconvincing regret, that it was simply not possible. He gave as a reason that the blind arches of the upper tier on the inside of the wall did not coincide with those on the outside.

(17)

I have been working on Victorian buildings for more than 20 years and have had many occasions to carry out brickwork repairs and reconstructions on similar brickwork arches and details to those of the shed wall. It was entirely obvious to me that subordinating the inner arches to the outer ones could be achieved with little difficulty if required and, in any case, the opening up of the upper tier of blind aches would not be essential but merely one of two alternative treatments that would permit the retention and incorporation of the wall in the new station entrance (exhibits I.7, I.9, I.10 illustrate the concept). The operation would indeed be more involved than simply breaking out brick infill from an originally open arch that had been bricked up. Nevertheless, it is a straightforward exercise that simply requires some patience and competent bricklayers. I asked the contractors who regularly carry out this kind of work for my Company to give me an informal estimate of the cost. Their suggestion was that the works would cost no more than 15 000 per bay. At that price they would be keen to do the work themselves.

(18)

It is notable that this particular justification for demolishing the wall had been completely abandoned by Network Rail when they came under pressure to explain their proposed demolition some months later. It had however been maintained at least until the applications were submitted on 27 June (exhibit E.5)

(19)

It became obvious that getting straight answers from Network Rail was going to be hard work. Mr Drabble had refined a response to any question about alternative design solutions that essentially ran to the effect that no solution other than that proposed by Network Rail is physically possible despite the best efforts of their engineers and architects to find one. When asked to explain the alternatives explored by Network Rail he would always refuse to answer.

(20)

To raise local awareness of the issues involved in the London Bridge redevelopment and in the hope that in a more critically focused forum we might make more progress BVAG hosted its own briefing from Network Rail on 19 May. Mr Drabble again gave the presentation, accompanied by his then PR man, Simon Brooks. At the presentation Mr Drabble again ran through a collection of slides. The images were almost exclusively what are sometimes referred to in the architectural profession as fluffies i.e. impressionistic renderings (exhibit E.6). Only one of the 7

slides presented gave a plan of the proposed concourse that could be used to enable our team to evaluate Network Rails proposals in any detail and to consider how any alternative design could meet the requirements of the brief. (21) Mr Drabbles presentation to BVAG had been well attended and there were many varied questions put to him from local people with a wide variety of concerns. The discussions had been of a very general nature and had not permitted any focused discussion of the necessity for heritage losses or any alternatives to such losses. At the end of the meeting I therefore requested a more focused meeting involving specialists assembled by BVAG and Network Rails architects, Grimshaws. I can remember Mr Drabbles precise words in response, which were We talk to anyone. He subsequently found himself having to retreat from those words. (22) BVAG assembled a group of conservation and railway architecture specialists and proposed a meeting at which it would be possible to look in some detail at the possibilities for retention of some of the heritage at London Bridge, as against Network Rails proposed wholesale demolition. Mr Drabble clearly thought it was difficult to refuse such a meeting and he agreed, somewhat grudgingly, to schedule it for 10 June. Our delegation was to comprise: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) Chris Williamson of Weston Williamson Architects Benedict OLooney, Architect (formerly with Grimshaws) and Southwark Conservation Areas Advisory Group chairman Paul Dobrazczyk, Architectural historian and specialist on the work of Charles Driver Neil Marshall of the Transport Trust Chris Costelloe of the Victorian Society Edmund Bird, Heritage advisor for Transport for London BVAG members comprising Jennie Howells (local historian), myself and my assistant, Liz Ruffell (23) Mr Drabble started to become uncommunicative in the run up to this meeting (not responding to our emails about the location etc.), giving the clear impression that he regretted ever agreeing to it (exhibit E.7). Eventually, on the 7th of June, Mr Drabble 8

backed out of the meeting on the grounds that we had not submitted concrete plans for alternative designs to him. This was obviously disingenuous as the meeting was for the purpose of obtaining enough information and drawings upon which our team could base our alternative design proposals. It is obviously not possible to put forward meaningful design suggestions without survey drawings or a brief. (24) Mr Drabble proposed to re-schedule the meeting but only for long after Network Rail had submitted their planning applications, which they did on 27 June. In the meantime he made approaches to certain of our delegation to invite them to individual meetings and thereby divide them off from the group initiative BVAG had instigated. (25) This incident was a clear demonstration of the conflict that Network Rail had to address between giving an impression of interest in consultation and consideration of alternatives to the damage to the historic environmental entailed in their proposals (as required by the EIA Directive) and in fact being uninterested in any alternatives, (that would inevitably increase the cost of the project). (26) After Mr Drabbles cancellation of our meeting we sought an alternative way to obtain sufficient information to produce some alternative proposals to save some of the threatened heritage. We asked for a copy of the briefing images that had been presented at the BVAG meeting with Mr Drabble so that we could use them to make alternative proposals for Network Rails (and the planners) consideration. If we were provided with the concourse plan it would have been possible to produce a sketchy proposal of how the retention of the wall was compatible with the general plan. It was however necessary to have a copy of that plan at sufficient resolution for it to be legible, as the version available to us was not. Our attempts to obtain a useable copy of the proposed concourse plan are recorded in an email thread (exhibit E.7a-d). By 23 June we were still being fobbed off with even more fluffy images that Network Rail knew to be of no use to us (exhibit E.8). (27) Our meeting at Grimshaws was eventually rescheduled for August 10 but some of our delegation were then on holiday, others had been invited to private meetings by Network Rail, and Edmund Bird was unable to attend having discussed it with his 9

manager. Edmund Birds job is funded by English Heritage. Those remaining, and who duly attended, were Chris Williamson, Neil Marshall, Jennie Howells, myself and Liz Ruffell. In any case, at the meeting it was obvious that so far as Network Rail were concerned the designs were finalised and there was no question of any changes being incorporated in response to consultation. We were shown the project in slightly greater detail but not invited to propose any reconsideration of any aspect of the designs proposed. For me, there were two memorable aspects of the meeting. The first was that there was an obvious unstated concurrence by the architects that the necessity to work around the London Dungeon had severely compromised the design freedom they had been given. The second was seeing the physical 3d model of the proposals that was on display in our meeting room at Grimshaws offices. This made it very clear how readily the existing south wall of the train shed could continue to serve its present purpose within the proposed new treatment of the station. i.e. it could carry the proposed new roof over the terminating platforms, just as it carries the present Victorian one, and it could provide the entrances to the new concourse through the existing arches (exhibits I.4, I.9, I.10 illustrate the principle) (28) The possibility of demonstrating the compatibility of the existing south wall of the train shed with the Grimshaw proposals was obvious. If we could have a photograph of the model on display, working in Photoshop, in which several of our members are skilled, we could produce images that would prove our point. This plan was however again foiled by Network Rail. (29) On 16 August we emailed the lead architect on the project at Grimshaws, Declan McCafferty, who had been present at our meeting, asking if we might have some photographs of the model. Mr Drabble was copied in on this request, which he quickly refused. His explanation was dismissive and he was annoyed that we had contacted Grimshaws (exhibit E.9). (30) By this stage it had become clear that Network Rail was not about to cooperate in any consideration of alternative plans to those they had submitted to LBS in their applications. BVAG was thus only left with the option of making our case to Southwark Council by way of representations and raising public awareness of the 10

scale of the threat to our local historic environment by the proposed heritage loss. Unfortunately, we had experience of public consultation in planning matters being a formality of which they would take no notice and so we were not optimistic that we would be heard. (31) It is an open secret that for any significant applications Southwarks planning committee is effectively subject to a party whip. (I only have any significant experience of planning in Southwark but I have no reason to think it is different elsewhere.) Together with the knowledge that there was no possibility of the London Bridge plans being put forward to the committee with anything other than a recommendation for approval this meant that there was not much that BVAG could do to deflect the plans from their predictable passage. We also knew that the next two stages of the approval process, the GLA and the Secretary of State, did not hold out much better prospects of giving us a fair hearing. We nevertheless continued raising public awareness of the heritage threat and stressing to Southwark Council that there were alternatives that could avoid such damage to the historic environment. (32) (1) (2) On 25 August the GLA produced their Stage 1 report on the applications. It included observations of significance to the effect that: They could not see why it was necessary to demolish the southern flank wall of the train shed (paras 59-60) That they were disappointed that the new station would not have an overall roof but merely shelters along the platforms that are otherwise open to the weather (paras 50-55) (3) The possibilities for incorporation of the SERO in the redevelopment had not been considered (para. 49) (33) We produced some Photoshop images to show how readily the southern flank wall of the train shed and the SERO could be opened up to provide entrances to the new station concourse (exhibits I.4, I.5, I.6). In the case of the flank wall no significant modifications would be required as it already comprises open arches at ground level. The upper tier could be opened up or not. With the SERO the bay structure of the building also permits the ready opening up of double height 11

openings with negligible injury to the building. Behind the facade of the SERO it would then be necessary to hollow out the building in that part of the ground and first floor that would become effectively an extension of the new concourse. These images were widely circulated on our website, posted up in our office windows, used on our flyers and shown in an exhibition of heritage under threat that we put on in our information office to from the date of its opening on 17 October. There was overwhelming general preference for this heritage-sensitive approach. (34) The Leader of Southwark Council, Peter John, was invited to speak at the opening of our office which he did. He was shown around the exhibition and the heritage loss involved in the Network Rail proposals and he was made very aware of our members anger at the insensitivity of the plans to the heritage of London Bridge. He was shown the images we had produced to demonstrate how readily the heritage buildings could be incorporated into the new station design. (35) Mr John was non-committal about his position on the heritage threat but he did say that he was due to meet David Higgins, CEO of Network Rail, the following Tuesday (25 October). Worryingly, from the point of view of BVAGs broader objectives as well as for the railway heritage campaign, Mr John was candid about his aspiration to see high-rise buildings on the south side of St Thomas. His reasoning was that such buildings would enable the Council to raise large sums of money from developers that could then be used to improve housing in more deprived areas of Southwark. This was worrying for our broader objectives as we have always regarded St Thomas St as the front line in the preservation of the character of the area now known as Bermondsey Village to the south of the railway lines into London Bridge. It was worrying from the railway heritage standpoint since the listed structures of the viaduct arches and the train shed wall must be taken into account when planning applications in the immediate vicinity are being considered. Hence, the more of the heritage that could be swept away by the station redevelopment, the less the obstacle to Mr Johns high-rise plans for the south side of St Thomas St. (36) Some time later we enquired about the substance and the outcome of Mr Johns meeting with Mr Higgins. First this was to the case officer, Gordon Adams and 12

subsequently by direct enquiry to the Leader himself (exhibit E.10) but he did not return my emails and therefore I eventually made the enquiry under the FOIA. Ultimately we were told that the meeting had no agenda and that there were no minutes or records of it. Later this chimed with similar contacts that occurred between the Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, and Mr Higgins, details of which have been equally impossible for us to obtain. (37) At the end of 2011 (during December), I and numerous other BVAG volunteers spent many hours on the street outside the SERO on Tooley Street and the train shed on St Thomas St talking to passers by and raising a petition calling on Southwark Council and the GLA to reject proposals for demolition of these heritage assets (exhibit E.11). We were not optimistic that either Southwark Council or the GLA would take any notice of the petition as they did not. However, it did give us a real insight into the attitudes of people on the street to the demolitions proposed and provided us with a means of demonstrating popular feeling for another day. We quickly raised 5 000 signatures and it was very apparent that there were only two sentiments to be found among the public: indifference or disapproval of the proposed demolitions. There was no significant support for the demolitions proposed. (38) Shortly before the Southwark Council planning committee meeting that approved the London Bridge plans on 20 December a copy of the 5 000 signatures raised was presented to Simon Blanchflower of Network Rail at their offices at Blackfriars and to Southwark Council and the GLA. (39) In addition to presenting our petition BVAG put together a short summary of our objections to the proposals for the Southwark planning committee members, mainly in the form of images, in a bound document which was sent to them by email and in hard copy form (exhibit E.12). (40) The officers report to the committee provided only entirely misleading or unconsidered reasons for the demolitions proposed. The way that the proposed demolitions were addressed by planning officers is examined in more detail later in this statement along with other matters that became clearer following FOIA 13

disclosures somewhat later. However, for coherence of this narrative it is necessary to briefly address certain flaws in the report. Specifically it states: of the demolition of the trainshed: the removal is necessary a result of the new track alignment proposed, and essential to the Thameslink scheme. and in particular its roof: preservation of the building is best achieved through salvage (41) These statements are misleading in that the issue of preservation of the southern flank wall of the train shed is circumvented by the implication that it must go for the same reason as the roof. This inference is made despite there being numerous references to the separability of the wall and the roof as conservation subjects (exhibits E.13.b, E.14.a) including officers own emails (exhibit E.15), the comments in the GLA Stage 1 report (exhibit 16, paras 59-60 ) and Network Rails own application documents (exhibit E.5). Furthermore, the last approved (2008) scheme, that followed two public inquiries that more fully considered conservation issues, anticipated salvage for re-use of the roof but retention of most of the wall (Exhibit E.17.b, E.18). (42) The remarks on the salvage of the roof structure (referred to as the building) are also wholly misleading given that the, less than transparent, legal obligation imposed upon Network Rail as part of the consent is to save any or none of the ironwork of the roof structure and supporting columns at their (or their contractors or consultants) own discretion (E.19). This compares with the 2008 obligation to salvage the roof structure and ironwork fully to enable the structure to be reerected in a new location. Of the demolition of SERO: demolition is necessary in order to achieve the large north-south concourse that has been identified as vital to the scheme. (43) The statement that the demolition of the SERO is necessary to achieve the proposed concourse is simply false. As the report itself later acknowledges, the 14

SERO does not obstruct any element of the proposed new station. Its demolition is proposed not to permit the erection of any other part of the new station but to provide an open space in front of the Tooley St entrance. The preservation of the SERO would not alter the proposals in that there would be no physical conflict between the proposed and the existing but it would require a quite different treatment of the Tooley Street entrance, whereby part of the existing building would become a kind of vestibule or extension to the main concourse. Again, contrary to what the report implies, the 2008 scheme entailed demolition of only part of the SERO, namely the westernmost 6 bays (exhibit E.17.c) Of the demolition of the westernmost arch of the listed arcade in St Thomas St: some direct works to the Designated Heritage Asset of the Railway Viaduct Arches on St Thomas St, listed at Grade II and the Joiner Street Bridge, listed at Grade II. (44) The proposed demolition of the westernmost arch of the St Thomas St arcade is concealed by adoption of the euphemism direct works. The suggestion that this demolition is beneficial to the historic environment speaks for itself. This obscurantist device was effective enough that even BVAG volunteers who had followed the plans closely did not realise what was actually proposed for some weeks. By concealment of the demolition of the last bay of arches in the arcade the planners deflected attention from their avoidance of established procedure on demolition of listed buildings. Oddly, on 1 July, when English Heritages listing advice report was produced they apparently did not know of the proposed demolition of the westernmost bay of the arcade. (exhibit E.2.g) (45) It is also worth noting at this stage that there is some obvious tension in the officers report. There are several references to officers disagreeing with the Environmental Statement (ES) submitted by Network Rail. This is not a particularly bold statement as would be difficult to agree with a document that describes demolition of historic building as beneficial to the historic environment and the demolition of the train shed wall and its replacement with a modern entrance built of pre-cast concrete with brick facing as retention of ground floor arches of external flank wall as part of new design (exhibit E.20). There is nothing in the report to indicate that officers sought from Network Rail revision of the ES that 15

would make it less of a mockery of the EIA process. Indeed, they go on elsewhere to praise design elements of the proposals in florid terms (para. 167) and continue to shield them from the scrutiny to which they should have been subjected under established national and European policy on heritage assets with unconsidered justification for the demolitions proposed. This conflict is illuminated somewhat by the FOI disclosures we obtained subsequently and which are dealt with later in this statement. (46) The officers report makes no reference to financial considerations in relation to the proposals - of which they were made aware through numerous documents and emails. These are considered later along with other evidence disclosed subsequently under FOI. (47) At the planning committee meeting itself on the evening of 20 December a large number of BVAG members and others objecting to the heritage loss at London Bridge attended to make their feelings known. The Chairman of the Committee, Nick Dolezal, exercised his discretion in treating the four Network Rail applications as one and thereby limiting representations from objectors to a total of three minutes between them. Simon Blanchflower of Network Rail spoke to the committee for about 10 minutes commending his companys proposals. His justification for demolition of the SERO was put in terms of safety of railway passengers but it was too vaguely expressed to evaluate its substance. He made assertions about passenger numbers and pedestrian flows and their safety implications that do not appear to be substantiated in any of the application documents or in submissions to English Heritage in support of the proposed demolition. He offered no justification for demolition of the train shed wall. The objectors divided their time allowance between myself and Benedict OLooney, Chairman of the Southwark Conservation Areas Advisory Group. This gave us 90 seconds each to make our case. I focused on the train shed wall and Benedict spoke about the SERO. There was of course great support for what we said from the large group of objectors present but, as anticipated, only modest interest from the minority Liberal Democrats on the committee and none whatsoever from any of the Labour majority. The consent was duly approved subject to a legal

16

agreement to be concluded no later than 30 March and referral to the GLA and the SoS for Communities and Local Government. (48) Following the decision of the Southwark Planning Committee we did at least know on what arguments the planners were going to peg their approval. This triggered an inquiry into their substance since, as cited above, some of the reasoning was perverse. (49) At the end of December I started to question (by email) English Heritage on the logic behind their decision to allow the loss of the south flank wall of the train shed to go by default by treating it as being implied in the removal of the roof. This dialog was terminated by Paddy Pugh, Head of the London Region of English Heritage, when he ceased to respond to my questions that focused increasingly specifically on the arbitrary (and floating) demarcation of convenience between the trainshed wall and the viaduct arcade. (exhibit E.21). (50) I also questioned Bridin OConnor of Sothwark planners (again by email) about their statement (At para. 186) that A study into parts of the building that could be accommodated in place has revealed that just one of the12 bays and a small portion of the flank wall on St Thomas St could be salvaged but this represents less than 10% of the structure. (exhibit E.22) (51) When English Heritage refused to respond to my emails I turned to the FOI/EIR provisions for obtaining information from them. This attracted a less than cooperative response. My requests were reinterpreted by them to exclude much of the information I had requested and that which they did disclose was heavily redacted. When I challenged this they refused to cooperate entirely, maintaining that they were exempt from complying with my disclosure requests as they were manifestly unreasonable. As a result we have an outstanding complaint before the Information Commissioner and still very limited disclosure from EH. However, following correspondence with the Chair of EH, Baroness Andrews, which included a suggestion that their stance at London Bridge may be susceptible to judicial review, limited email communication was resumed with Mr Woods.

17

(52)

My questioning of both Bridin OConnor and Malcolm woods (exhibit E.23) led both to ultimately admit that they knew of no necessity to demolish the south wall of the train shed. I also questioned the case officer at Southwark, Gordon Adams as to the whereabouts of the study that established the necessity for demolition of the south wall. He would only ever say that it was all in the papers but, told that I couldnt find it, he refused to say where. I was not the only one who couldnt find the justification for the demolition as Giles Dolphin, Head of Planning Decisions at the GLA, told me he could not find it either.

(53)

On 12 January I spoke to Mr Dolphin who was, unfortunately, due to retire the following day. He thought that the proposed demolition of the train shed wall was unnecessary and that the comment in the GLA Stage 1 report that it was not clear why demolition was said to be necessary had not been answered. He told me that he had just written to Network Rail asking for a justification for the demolition of the wall (exhibit E.24). Knowing of the existence of this request, after he left, I sought disclosure of both Mr Dolphins question and Network Rails answer (exhibit E.25)

(54)

By this stage the application was with the Mayor of London for his consideration pursuant to his powers to refuse the application or to determine it himself if he saw fit.

(55)

The Mayors decision is required to take place within fourteen days of the application being referred to him but it was delayed several times. We were not able to obtain a clear explanation for the delay. We were told on at least one occasion that it was because Southwark Council had withdrawn the application but if this was the case it was immediately re-submitted. Although we had not thought it likely, BVAG began to think it possible that the Mayor would balk at the heritage loss being proposed, perhaps even having taken a closer look following a demonstration that our group had organized outside County Hall. That demonstration, timed to coincide with the meeting at which he was supposed to make a decision, on 1 February, resulted in a lucky (for us) encounter with the Mayor himself who was taking a photo-call on the lawn outside the GLA building. This enabled us to ambush him, as the local news website put it. As a result of this 18

opportune ambush we were able to put our case against the heritage destruction far more thoroughly and forcefully than we had expected to be able to with just placards and a megaphone outside County Hall. (56) The chance meeting with Boris Johnson enabled us to spend some time making our point as he remained talking to us for some while. At one point, as the local news site reported (exhibit E.26), he told us: I dont mind ending up in court, Id love to stop this bloody thing. I cycle past that thing (SERO) every day and it infuriates me that we could lose it. Less encouragingly, he also said he had been advised by lawyers that it would be costly to the GLA to save the buildings. We did not know what cost he was referring to but another of our supporters who had approached him at a public engagement he had been attending had been told the same thing so we considered there was obviously something to it. As he left I told Mr Johnson that there were a bundle of papers that we had already submitted to his planning officers (exhibit E.27) that he should consider as they made clear that a decision to allow the applications would be vulnerable to legal challenge. In the event the Mayor did not make a decision at that meeting and it was again postponed. (57) On 14 February I had received by way of response to my FOI request (made on 16 January) a copy of Mr Dolphins email to Network Rail (exhibit E.24) calling for a justification of the proposed demolition of the train shed south wall. The response to Mr Dolphins email, which was from Network Rails consultant Erica Mortimer of CgMs was forthcoming later, on 16 February. This was a patronising document (exhibit E.25) that gave numerous unsustainable justifications for the proposed demolition and various blunt assertion of the necessity for it. None is valid. One was that such demolition was already approved as a result of a previous application. Apart from being irrelevant to the consideration of a new application which must be considered on its own merits and in relation to prevailing policy, this statement was untrue. In fact the 2008 application included a Design and Access Statement (exhibit E.17.b) that reads: The south wall of the listed trainshed, which is of some interest and contributes positively to the streetscape, will be largely retained and incorporated into the new station. (para. 7.1). It seems the partial demolition of the wall proposed was to facilitate a widely mocked element of the 2008 scheme: the construction of an air rights office block over the railway lines that was no 19

doubt a product of the economic euphoria prevailing when the scheme was conceived (exhibit E.18). (58) As it was clearly possible to preserve the flank wall in 2008, it was impossible to explain why it was not possible today. So CgMs re-wrote history on behalf of their clients, Network Rail. (59) The other justification for the demolition was illustrated with a photograph of a long steel beam on the trailer of an articulated lorry. This was to assist planning officers in understanding the proposition that long steel beams would be used to carry the tracks over the hollowed-out viaduct below to create the wide street-level concourse. As I had already explained to the case officer at the GLA, Matt Carpen, beams that can be put in in one piece can also be spliced and put in in smaller sections. I told him that if he didnt think this was obvious but rather that it was a matter for an engineer I could provide him with such confirmation from a structural engineer. (60) I had also emailed Nick Gray, Principal Programme Sponsor of the London Bridge project at Network Rail, on 20 February (exhibit E.28) challenging him to explain the specious justification provided for demolition of the south wall by Ms Mortimer of CgMs. He responded on 27 February (exhibit E.29). His words are carefully chosen but he does not contradict my assertion and explanations as to why both of Ms Mortimers justifications were unfounded. Mr Gray also confuses the 2003 scheme with that of 2008. This is indicative of how the claim that the principle of the demolition of the train shed wall had been established became a mantra for the planners, for English Heritage and for Network Rail in their advocacy of the present proposals. It appears that many of the parties relying on this false assertion did so by repetition and on the basis of no knowledge of the reality. (61) Mr Carpen had been copied in on Mr Grays letter. Following the three postponements, the Mayors decision was now due to be made on 1 March. To make sure that there could be no excuse of not receiving or not understanding our representations when it came to considering whether there was any necessity for demolition of the south wall of the trainshed I had a long conversation with Mr 20

Carpen on the phone and emailed him with confirmation that he could not rely on long beams or planning precedent to justify the demolition (exhibit E.30) (62) Eventually the Mayors decision was made on 1 March. It came under the signature of his deputy, Sir Edward Lister. The Stage II report (exhibit E.63) that gives the reasons for the decision was emailed to BVAG on 2 March. Knowing that the demolition of the south wall was unjustifiable I was keen to see how Mr Carpen had dealt with the problem in the report. (63) His solution is exemplary of the planning officers craft. At para. 60 of the the Stage II report he records that the GLA has not been provided with a copy of a construction logistics study that had been requested to justify the demolition. At para. 61 he recites the policy requirement that necessity for demolition of the wall must be established. At para. 62 he acknowledges that it is possible to build the station without demolition of the wall and then goes on to assert the opposite. Ultimately he relies on the long beams argument that he knows to be unsustainable. On the telephone Mr Carpen had not challenged my assertion that it is obvious that long beams can be achieved by splicing together shorter ones. Nor had he taken me up on my offer to provide an engineers report proving that it would be possible in this case. I have since challenged Mr Carpen on his self-contradictory comments in the report but he has declined to answer the questions I put to him (exhibit E.30) (64) This is just the most obvious example of how the London Bridge proposals were approved without proper scrutiny of the proposed loss to the historic environment. Throughout the planning process BVAG was watching the planners more closely than they are used to. It became obvious that the plans were sanctioned at a higher level and planning officers would simply be required to accept that policy would have to be circumvented and they would be expected to do the best job they could of pretending there was compliance. The obvious supposition was that the demolition-minded approach to the redevelopment was driven by financial considerations. This is corroborated by the various FOI disclosures we obtained subsequently in which there are frequent references to cash constraints on the project (addressed more fully later in this statement). There is no reference whatever to cash constraints in any of the public documents. This obviously means 21

that planning officers knew that they were expected to operate in a regime of secrecy in this respect. (65) In accordance with all the planning documents going before, BVAG, believed that, following clearance from the GLA, the proposals would be referred to the secretary of State. When the Mayors decision to leave Southwark Council to determine the applications was sent to us on 2 March I was away. It was therefore another member of our Group, Amy Blier-Carruthers who made enquiries of Southwark Council and the DCLG as to the progress of the application until I returned. Amy reported difficulty in getting a response to her inquiries and general evasiveness as to if and when the application had been referred to the SoS. (66) When I came back to the UK on 12 March I took up the issue alongside Amy. My experience was identical to that which she had reported whilst I was away. For the DCLGs part I was required to deal with a Ms Michelle Peart who was clearly a not a very senior official in the Planning Casework Unit. It was very clear that Ms Peart was being closely directed from above. Telephone conversations (and email communications) with her were difficult as she seemed to be working from a tight script. The last time I had occasion to deal with the DCLG on a referred application in which BVAG was interested I had been able to engage much more meaningfully and with someone obviously more senior and experienced. It was odd that for a much more important application I was only able to make contact at a much more junior level. (67) Eventually it became clear that, contrary to what all the planning authorities documents had stated, there was to be no referral of the applications to the SoS by Southwark Council. It is presently not clear how it happened that the stated intention to refer the applications to the SoS was abandoned. (68) In any case, again knowing that current policy on call-ins is to avoid them, we made our appeal to the SoS regardless (exhibit E.31). It became very apparent from our contacts with DCLG that declining to call-in the London Bridge proposals would be a formality. This was subsequently illustrated by the FOI disclosures obtained on 27 April (Exhibit E.32), again considered in more detail later. Another BVAG member 22

had however identified a requirement under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act to refer listed building applications to the SoS where they are for works involving a Transport and Works Act Order. It seemed clear that the listed building consents required in this case therefore had to be referred as a matter of law. (69) I pointed out this apparent legal obligation to Ms Peart and told her that in her department there must be lawyers specialised enough to give an immediate response to our interpretation of the legal position and asked her to obtain such advice. She was in contact with Southwark Council and clearly there had been consultation between the Council and DCLG about the legality of the decision not to refer the applications. By way of a response to my request to know the DCLGs own position on the matter I received a copy of an email from Bridin OConnor of Southwark Council to Ms Peart (Exhibit E.33) giving the interpretation of the law on which she relied for not referring the applications to the SoS. This was unclear to put it mildly and hence I was not persuaded that the legal position is not as it appears on its face. (70) Although they did not tell me, DCLG officials did obtain the advice of their lawyers on the effect of the Planning (LB&CA) Act. A copy of the email in which this appears was disclosed in response to my FOI request (exhibit E.32.g) but it has been redacted on grounds of privilege. I have requested its disclosure in un-redacted form as a matter of public interest and pursuant to these proceedings but it has been refused again. (71) From the FOI disclosure from DCLG it is clear that the Department for Transport lobbied for a swift dismissal of our call-in application in the form of a briefing on the London Bridge proposals (exhibit E.32pp). There are references in the disclosed internal emails to the necessity to dispose of the matter urgently in order to meet a deadline for the signing a legal agreement with Southwark Council and also to avoid the cost of the Community Infrastructure Levy being imposed following its introduction on 1 April. It appears clear from the documents that these considerations are what determined the SoSs approach to our call-in request.

23

(72)

The DCLG issued their Non-intervention notice on 29 March and Southwark Council responded immediately by granting consent for the proposals on the same day.

(73)

At this point we were left only with the option of considering challenging the decisions leading to the grant of planning consents in the Courts. We therefore proceeded to pursue disclosure of documents under FOIA/EIR. The impression throughout the planning process was that the approach to the redevelopment of London Bridge had been determined long before any planning application was made in the knowledge that the planning procedure would be a formality. Given that the plans involved wholesale destruction of the railway heritage of London Bridge it was clear from the start that the compliance of the planning officers of Southwark Council and the GLA, as well as English Heritage would have to be assured. Our FOI requests were made in this context.

Further consideration of FOI disclosures (74) The earliest documents that have been released to us regarding the current proposals start from October 2010. By that time a core team of people has been established for discussing the plans with Network Rail that consists of Southwark planning officers, the Case Officer from the GLA, the Area Adviser from English Heritage, Malcolm Woods and Network Rails planning consultants, CgMs. (75) Of course, Southwark planners, the GLA and English Heritage are all required to be on board if Network Rail are to succeed in obtaining consent for demolishing what is effectively all of London Bridge Stations visible Victorian Heritage. The process will require the LPA and the GLA to take a flexible approach to the application of local, national and European policy on protection of the historic environment. A key element in persuading the planning officers to take such a flexible approach to policy is the support of English Heritage, who are therefore central to the whole process.

24

(76)

Taking the parties in turn, our FOI requests have revealed further information and evidence in support of our Claim:

English Heritage (77) North Southwark has a long and rich history. Heritage and the historic environment are however a demonstrably low political priority for Southwark Council. The planning process is unreceptive to heritage interests and the historic environment has only English Heritage as a potentially effective advocate. (78) In the case of the London Bridge proposals the failure of English Heritage to act in defence of heritage assets was crucial. The perverse decisions and advice of English Heritage regarding the proposed damage to the London Bridge historic environment infected the decisions by all three statutory planning authorities to permit the redevelopment. (79) English Heritage have not been cooperative in response to our FOIA/EIA disclosure requests (exhibits E.34). The Information Commissioner is presently considering a complaint from BVAG against EHs refusal to give information on the grounds that it is manifestly unreasonable. The limited disclosure they did give us prior to their blanket refusal has been heavily redacted. The more important documents demonstrating the position of English Heritage were, furthermore, not included in their disclosures but have come from disclosures obtained from other bodies. (80) There are conflicts between what EHs Area Adviser, Malcolm Woods says to different people at different times, particularly in response to my questions to him posed sequentially by email (exhibit E.23)

On cost (81) One document that EH had disclosed to us revealed that Network Rail had told Mr Woods that preservation of the SERO would add 100 - 150 million to the cost of the London Bridge redevelopment (exhibit E.35). On 5 April (exhibit E.36) I asked 25

Mr Woods about any other discussions that EH had on financing of the proposals. On 10 April he responded that There were no other discussions regarding the financing of the scheme so there are no further details to give Im afraid. (exhibit E.37) (82) This statement is inconsistent with documents revealing how Mr Woods had himself expressed the position of English Heritage with regard to the financial constraints on the project and how he and the planning authorities had been pressurised by Network Rail over the cost of preserving heritage assets. Mr Woods references to such financial constraints in the documents long pre-date the discussions regarding financing that he acknowledges. (83) In an email exchange with Gordon Adams and others at Southwark on 11 July 2011 (exhibit E.38), Mr Woods addressed himself to the financing of the London Bridge plans, improperly taking account of cost issues in presenting the position and advice of EH. He says: First we are told that Network Rail is already struggling to fund this project from the funding granted it by HM Treasury and I recognize that cost is not normally a consideration when assessing heritage benefit, etc but I am wary of jeopardizing this project if it comes down to saving perhaps part of a fragment albeit quite a significant fragment of the grade 2 listed train shed. (84) On 26 May 2011 Edward Kitchen of CgMs wrote a six page letter to Malcolm Woods of English Heritage (exhibit E.39) quoting 30-40 million as an estimate of the cost of saving the train shed ironwork, supporting structure and roof by dismantling for storage and re-erection. (These figures dont correspond with other figures for the same works presented to Southwark Council by Network Rails own Railway Heritage Trust (exhibit E.40). Saving the ironwork had been a condition of the previous consent for demolition of the roof in 2008 that Network rail now wanted dropped. Mr Kitchen asked EH to consider whether such an obligation was a prudent and effective use of public money in the current economic climate. Council officers continued to argue for retention of the roof but without EHs support their position was abandoned. Network Rail got their way and the story of how Southwark Council progressively and furtively abandoned any requirement to preserve the structure, or any part of it, is a long story of its own. 26

(85)

On 30 November 2011 Mr Woods wrote to Chris Drabble of Network Rail (exhibit E.41): Hi Chris. I am not nagging but if you are able to let me have the statement of case we spoke of i.e. briefly why Network Rail believes the demolition of the Tooley Street building is necessary and what would be the consequences, including financial (broad figures are just fine), if it had to be retained before then that would be extremely helpful.

(86)

It was in response to this email Mr Drabble emailed Mr Woods on 1 December (exhibit E.35b) and again on 8 December (exhibit E.35a ) stating that, the impact of the retention of the SERO would be unaffordable and estimating that the cost to the scheme and ultimately the public purse could range between 100m to 150m. He concludes: Obviously any decision to retain 64-68 Tooley St is not something that Network Rail could support.

(87)

To put Mr Drabbles cost estimate into context, English Heritages call on public funds in 2010-11 was 130m. Although the figure quoted by Mr Drabble is obviously a gross exaggeration, it would lay EH open to the charge that they had doubled their annual cost to the taxpayer merely by insisting on preservation of then SERO.

(88)

As early in the pre-application process as 19 October 2010, a meeting of Southwarks Heritage and Design working Group was told by Network Rail that The whole station scheme at London Bridge is on a funding knife edge (exhibit E.42b). Although not present at that meeting it is inconceivable that Mr Woods was excluded from this information.

Precedent and justification for demolition of the south wall of the train shed (89) On 10 April Mr woods wrote: We knew that the previous scheme included the retention of part of the south wall of the listed train shed (90) This statement is at odds with what Mr Woods said in his letter to Edward Kitchen of CgMs on 31 August 2011 (exhibit E.43): As with the consented scheme, the 27

current proposals to redevelop the station call for the complete demolition of the grade II listed train shed that encloses platforms 9-16 of the station. His letters to Southwark Council of 13 December 2011 (exhibit E.44) and DCLG of 5 January (exhibit E.45) are similarly misleading. In the latter he refers to a scheme proposed in 2000. We are still seeking details of that scheme from Southwark Council but, in any case, Mr Woods was fully aware that that scheme was superseded, following two public inquiries, by the 2008 scheme which preserved most of the train shed flank wall and the entire roof structure (albeit through salvage for re-erection). (91) On 4 April he had written: retaining just the south wall whether in whole or in part - was not something that we would set as a condition of any consent that might be granted. and We did not consider the south wall as a separate entity and apply a necessity test to it alone. (92) The suggestion that EH did not consider the south wall in its own right as a structure worthy of retention is at odds with its own previous position from earlier public inquiries (exhibit E. ), with the opinions of both planning authorities (exhibits E.24, E.46, E.47), with architects of the previous and current schemes (exhibits E.17, E.5), with the report of Network Rails own planning consultants (exhibit E.3e) and with the overwhelming opinion of conservationists and the public. It is also at odds with the physical reality of the continuity of the train shed flank wall and the separately listed St Thomas St arcade that represent one continuous faade (exhibit I.1, E21a). For these reasons, identification of the flank wall with the ironwork of the train shed is an untenable and perverse position for EH to have taken. It can only be explained by a desire to release Network Rail from the presumption in favour of retention of heritage assets that planning policy entails. On demolition of the westernmost bay of arches in the St Thomas St arcade (93) Although relatively minor in the overall scale of heritage loss proposed in the ondon Bridge redevelopment, the demolition of the westernmost arch of the recently listed St Thomas St arcade is instructive. It illustrates how fully the planning process followed a pattern of acceptance of the premise that Network Rail would be at liberty to demolish whatever they chose and the planners and English Heritage 28

would have to make it fit with conservation policy by whatever means they could. In the case of the westernmost bay of the arcade this involved particularly convoluted and inconsistent approaches by the various parties. (94) The listing of the St Thomas St arcade in July 2012 had necessitated a new listed building consent application to augment the June applications. As I explained earlier in this statement (para. 4), Mr Woods was well aware of the unity of the train shed and the St Thomas St arcade as it was he who had invited BVAG to propose removing the ambiguity about where the one stopped and the other started. The listing of the arches had effectively made the arcade and the train shed wall one continuous listed structure, albeit listed under two separate reference numbers. (95) The continuity of the shed wall with the arcade makes it impossible to demarcate between the two structures. EH had removed themselves from the obligation to defend preservation of the shed wall by maintaining that it was unworthy of preservation once the principle of the removal of the roof structure was accepted. As explained above, this position is untenable and at odds with all other parties views, including EHs own in the past. However, it also produced another problem as a result of the continuity of the building with the newly listed arcade. I explored this difficulty in EHs abandonment of the shed wall as a conservation issue in an email thread with Mr Woods superior, Paddy Pugh, at English Heritage in December and January 2011/12 (exhibit E.21). I pressed Mr Pugh on how EH thought a demarcation could be drawn between the train shed and the arcade. When he refused to respond I sent him a photograph of the conjunction of the two and asked him to select between four different options marked with different coloured dotted lines. (exhibit E.21a). Mr Pugh eventually refused to respond to me entirely without answering the question. (96) The problem of the last bay of the arcade also prompted different responses from different parties. Southwark Council did not refer to the proposed demolition of the bay in the listed building consent application description (exhibit E.48) and obscured it in the officers report to the planning committee by referring to direct works rather than demolition. The drawings submitted by Network Rail in that application misstated the extent of the listed arches to exclude the bay of three 29

proposed for demolition (exhibit E.49). By these means Southwark Council concealed their decision not to refer the proposed demolition of the last of the newly listed arcade bays to English Heritage and the Secretary of State. This was done with the knowledge and support of Mr Woods (exhibit E.50) although he distances himself from the decision in his email to DCLG (E.32) (97) Recognising the integral nature of the arcade to the shed wall would have made the EH position that the wall did not merit conservation impossible to propose. Effectively, they would have to maintain that the wall was not just continuous with the ironwork of the roof but that it was discontinuous with the arcade. Manifestly, as was recognized in the consented 2008 scheme, the reverse is the case. Listing of SERO (98) On 12 December 2011, English Heritage submitted their advice to DCMS on the review of their recommendation not to list the SERO pursuant to a request from the Victorian Society made on August 19 (exhibit E.51). The review had been signed off by the EH area Designation Adviser, Patience Trevor, on 29 September 2011 and by her superior, Delcia Keate, on 11 October. Recently I enquired of the DCMS if they knew why it had taken two months for the review to reach them, but they did not. (99) Obviously, the applicants, The Victorian Society, other heritage groups, interested individuals and BVAG members were disappointed (and dismayed) that EH had reaffirmed their position on SERO. In exasperation we researched the EH listings of other buildings by Charles Barry & Sons and other listed buildings in the immediate vicinity of SERO. In addition I called Ms Trevor of English Heritage to ask her about a unique feature of the SERO building that I wondered about, but that her report did not mention. I also asked her about her unfavourable comparison of the building with the North Eastern Railway Offices in York. I was concerned that when I asked her whether the unique chequerboard relief on the upper levels of the buildings exterior were executed in red brick or in terracotta she told me she didnt know as nobody had asked her to look at it. Similary, when I asked her

30

where in York I could see the North Eastern Railway offices for myself for comparison, it was obvious she didnt know. (100) We discovered that English Heritage in the past have listed almost all of Charles Barry juniors other buildings, many of which are very modest in comparison with the SERO. An obvious example is Dulwich College Prep School (exhibit I. 16, E.52). All these factors contributed to a widespread belief among heritage groups that English Heritage had been influenced by the Network Rail proposals for London Bridge in their recommendation to DCMS on the importance of the SERO. (101) As cited above under Cost, on 1 December and 8 December 2011 Mr Drabble emailed Mr Woods and informed him that saving the SERO was unaffordable as it would cost 100 150 million. There is no suggestion that the building could not be saved and incorporated in the new station proposals. Shortly after this English Heritage confirmed their recommendation to DCMS that the building should not be listed. Clearly, to have recommended otherwise would have been to put them in direct confrontation with Network Rail. In order to properly make out our case we require proper disclosure from EH that they continue to resist. (102) Ultimately, EH did not entirely concede on demolition of the SERO, maintaining that the case was not made out (exhibit E.44), but by not recommending the building for listing and by failing to maintain any objection to the decision of Southwark to permit demolition they effectively turned a blind eye to its loss. This stance is illustrated by an email of 25 November 2011 (exhibit E.53) from Mr Woods to Gordon Adams. He says, we are struggling to get a compelling case out of CgMs/Network Rail to justify the demolition of the Tooley St building: Edward Kitchens latest letter following our meeting was not what we hoped for. He also seeks to agree a form of words that preserves for English Heritage some claim to integrity but ensures any obstacle to Networks Rails demolition plans and Southwark planners freedom to recommend approval to their planning committee is minimised.

31

(103) In summary, there is persuasive evidence, even from the limited disclosure EH have given, that they acted with regard to commercial and political factors that were outside their remit and they thus failed in their legal duty to secure preservation of historic buildings.

Southwark Council (104) In the early pre-application discussions between Southwark Planners and Network Rails consultants the planning officers show belief in the application of established policy to the London Bridge proposals. On 29 November 2010 the case officer, Gordon Adams, in an exchange of emails with Malcolm woods of English Heritage (Exhibit E.54) is having to make the case for retention of the south wall of the train shed against apparent opposition from Mr Woods. He concludes the exchange with an announcement of a shot across the bow of Network Rail to put them on notice that there are fundamental concerns with their proposal. It is particularly relevant to subsequent developments that the issue of previous planning consents and what precedent there is for demolition of the wall is canvassed. Subsequently there appears to evolve a consensus to adopt the pretence that there is persuasive precedent for total demolition of the wall. Mr Woods even acknowledges that the whole of the train shed wall could be retained but he says that this would not be the preference of English heritage, or at least, they would not be ready to express such a preference. (105) On 30 November 2011 Bridin OConnor writes what is presumably the shot across the bows referred to by Mr Adams (exhibit E.46). This includes the demand: More importantly evidence will be required to demonstrate that all options have been considered for the retention of any listed or conservation area structure that is proposed for demolition. (106) Considerably later, in an email of 12 July 2011 (exhibit E.55) Mr Adams writes: What is being put forward is taking a substantial amount of heritage fabric and there will be very little of early elements of Londons oldest mainline rail station left; accordingly we will continue to try and salvage what we can. 32

(107) This was in response to an email from Malcolm Woods of English Heritage (see under EH section) that referred to the financial considerations with which he was concerning himself. In response to that point Mr Adams says: And on the funding, chris Drabble was at pains to point out that the recent NR 1.2bn profit was reinvested in the railways perhaps they could invest a bit more in the London Bridge Scheme. (108) His P.S. is equally telling: Apologies if I am coming over a little negatively but I just come back from a tour of Kings Cross station which is more in line with the high aspirations we had for London Bridge. (109) These exchanges illustrate the way that fighting talk from the planning officers regarding conservation obligations in the early stages start to become tempered by resignation. The obvious inference is that, in this case, cash considerations will trump conservation policy. (110) By the time the proposals go before the planning committee and following a personal meeting between David Higgins of Network Rail and Peter John (of which we have been unable to obtain any minutes) there is no remaining concern expressed about reconciling the proposals with conservation policy. Neither is there any mention of monetary factors in the report to the planning committee. (111) This would of course be understandable if Network Rail had produced evidence to support the necessity for demolition of the heritage assets concerned. For this reason I continually questioned both Southwark Council, the GLA and English Heritage about the production of such evidence. This always drew the evasive response its all in the application documents as Giles Dolphin of the GLA also reported having been told. It is evident that Network Rail did not think it necessary to satisfy the conditions that would attach to any normal application for such large scale heritage demolition. There is therefore a missing link in the chain of events, which is how, without any significant changes to the proposals or consideration of alternatives that would reduce destruction of the historic environment, the defence of heritage assets in accordance with established policy was abandoned by planning 33

officers. We know that behind the scenes the cash card was being played fully by Network Rail (exhibits E.35, E.38, E.42, E.56c) but not how it became so effective in overcoming the planning officers objections. The GLA (112) As part of the troika that would be required to facilitate the London Bridge plans along with Southwark Council and English Heritage, the GLA was involved from the early stages of the pre-application process. Indeed, the case officer at Southwark, Gordon Adams, worked on an exchange basis with the GLA, spending part of his time in one job and part in the other. Of course he would not work on the same cases in both capacities but the interrelationship between Southwark as LPA and the GLA next door on a major public infrastructure project is obvious. Inevitably the approach taken to the applications was substantially agreed between the key parties. (113) The difference between the GLAs role and that of Southwark Council, as emerges from disclosure we have obtained, from BVAGs perspective is therefore limited to a few issues. By the time of the GLA decision we had also had some time to probe the justifications (such as they were) relied upon by Southwarks planning officers in their report and to obtain some FOI disclosure. It was therefore easier to pin down the GLA on specifics prior to the Mayors decision. The GLA responded accordingly to try to ensure their approval was JR-proof. (114) As recounted above, I had talked to Giles Dolphin, former Head of Planning Decisions at the GLA, on 12 January, the day before his retirement. I had previously talked to him on the same subject and I knew that in his opinion there was a most obvious lack of justification in the Network Rail proposals for the demolition of the St Thomas St. train shed wall. This point had been made clearly in the GLAs Stage I report at para. 60 (exhibit E.16b): Figure 7.8 and 7.10 of the Heritage Statement suggests that part of the wall needs to be removed; however it is not clear why. The configuration of the new concourse should therefore be shown testing retention of the train shed wall as part of the clear and convincing justification for the loss of heritage assets.

34

(115) Mr Dolphin told me that he had just written to Network Rail seeking such justification and that he thought in the absence of a satisfactory response the approval that he anticipated would be forthcoming would not be JR-proof. Once he retired we no longer had Mr Dolphin as a point of contact at the GLA but we pursued the trail of enquiries and disclosure applications that he had commenced. This ultimately led to the exchange of letters with Nick Gray of Network Rail and emails with Matt Carpen (exhibits E.28, E.29) that forced the self contradictory para. 62 in the Stage II report. The whole section of that report on retention options of the listed trainshed and trainshed wall (paras 58-67) is the product of a post hoc justification that became necessary because BVAG had put the GLA on notice that there was no adequate justification in the proposals as submitted and that alternative treatments that preserved the buildings had not been explored. It is fundamentally flawed in that it considers the compatibility of the proposed designs with retention of the building. The correct approach is obviously to consider designs that follow from the premise of retention of the heritage assets rather than to test the retention against designs conceived on the assumption of their demolition. This is no doubt why, several months before, Network Rail were so keen to prevent heritage minded design treatments being produced by the BVAG group of architects and heritage specialists. (116) The justification for the demolition of the SERO is a product of the same inverted logic. Obviously a design conceived on the basis of its demolition is not compatible with the retention of the building. Hence the necessity under the EIA directive for early and effective consultation and consideration of other options that would reduce damage to the historic environment. (117) On 20 October 2011, a sparingly minuted meeting took place between Network Rail executives and Deputy Mayor, Sir Ed Lister, Giles Dolphin and Matt Carpen of the GLA (exhibit E.58) This is significant because the relevant documents were not disclosed in response to our first FOI request but the documents that were disclosed gave us knowledge that such a meeting took place and we therefore made a further application for disclosure specifically in relation to that meeting. This in turn revealed Network Rails anxiety to conceal the extent of the monetary considerations behind the London Bridge scheme. Under FOI procedure a third 35