Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Frame Design

Uploaded by

suresh.srinivasnOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Frame Design

Uploaded by

suresh.srinivasnCopyright:

Available Formats

SOME ESSENTIALS OF FRAME DESIGN Basically, a frame house is one that's supported by its walls.

The walls, that is, do more than just enclose the house; they also hold it up. This contrasts with, say, post-and-beam construction, in which most of the weight of the building sits not on its walls but on horizontal beams supported by vertical posts inside the building. You commonly see post-and-beam design in barns, where the exterior walls are often too tall and flimsy to be relied on for support and where, because of the large spaces a barn has to enclose, there aren't enough interior walls to support the lofts and large roofs that barns generally have. Sometimes residential buildings combine frame design with post-and-beam especially if they have a very large downstairs space -- the living room, let's say. The rest of the downstairs, composed of smaller rooms, would be crisscrossed with enough walls to support the upstairs (which is why those walls would be called "bearing walls"; they bear the weight of the story above). But the big living room, being an expanse uninterrupted by such walls, might have to be spanned overhead by a number of beams supported here and there by posts. The outbuilding we'll be putting up, however, relies solely on its walls for support, so it's of pure frame design. Frame construction is probably the easiest kind for the beginner because structural members are comparatively light and easy to join together. It also requires only a minimum of engineering, and its basic principles can be mastered -- make that "comprehended," since mastery is somewhat beyond the scope of this book -- fairly swiftly. We'll start from the bottom and work our way upward. The lowermost -- and normally the most massive -- horizontal members of a standard frame structure are the girders. They usually run the length of the house, and in full-sized houses they're ordinarily doubled or tripled 2x12s. If the house has a concrete basement or crawl space, their ends often sit in depressions molded into the concrete called "girder pockets." And if they span any appreciable distance they're usually supported at regular intervals by cylindrical steel posts called "Lally columns." (The post-and-beam principle intruding once again.) The boards laid horizontally along the tops of the foundation walls arc called "sills" or "house sills." They're usually bolted to the foundation, and because they transfer their load directly to the foundation they're generally thinner than the girders. The top surfaces of the sills are level with the top surfaces of the girders, and for all practical purposes they function just as girders do.

Now, set at right angles across the tops of the sills and girders, come the floor joists. They'll most likely be 2x1Os or 2x8s or even 2x6s, depending on how much distance they have to span. If construction is conventional, the joists will be spaced at 16" intervals. Since they're sitting on their short side (the 2" side rather than, say, the 10" side), there's the chance they could twist, so if they span any appreciable distance between girders or between girder and sill, the joists will have either wooden or metal "bridging" nailed between them. The simplest bridging consists of sections of the same size boards as the joists themselves. An alternative method is called "cross-bridging," in which wood or metal struts are nailed crosswise between the joists.

Some basic parts of a frame structure (with some pieces cut away and a couple of walls missing).

You might also like

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Greek Letters As Math SymbolsDocument1 pageGreek Letters As Math Symbolssuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Probability (A Sample Write-Up)Document3 pagesProbability (A Sample Write-Up)suresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Adjectives: Taste: Bitter Spicy Bland Minty Sweet Delicious Pickled Tangy Fruity Salty Tasty Gingery Sour YummyDocument1 pageAdjectives: Taste: Bitter Spicy Bland Minty Sweet Delicious Pickled Tangy Fruity Salty Tasty Gingery Sour Yummysuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Color Adjectives List: 30+ Shades DescribedDocument1 pageColor Adjectives List: 30+ Shades Describedsuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Solution To System of EquationDocument1 pageSolution To System of Equationsuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Porter's Generic Competitive Strategies (Ways of Competing)Document1 pagePorter's Generic Competitive Strategies (Ways of Competing)suresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Merge SortDocument3 pagesMerge Sortsuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Geometry SymbolsDocument1 pageGeometry Symbolssuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Leaf Spring Failure AnalysisDocument3 pagesLeaf Spring Failure AnalysissomanathpawarNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- QualityDocument2 pagesQualitysuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- CalipersDocument1 pageCaliperssuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- CalipersDocument1 pageCaliperssuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Year Price Year Price Year Price: Gold (10 GMS) Price HistoryDocument1 pageYear Price Year Price Year Price: Gold (10 GMS) Price Historysuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Emergency Food Storage List For One Person For One YearDocument1 pageEmergency Food Storage List For One Person For One Yearsuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Yajur Veda Sandhya VandanamDocument16 pagesYajur Veda Sandhya Vandanamsuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Project Management ApproachesDocument1 pageProject Management Approachessuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Motivation 1Document2 pagesMotivation 1suresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- 10-Steps To DFMEADocument1 page10-Steps To DFMEAsuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Scribd Up LG22Document13 pagesScribd Up LG22suresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Pert 2Document36 pagesPert 2suresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Project Management ActivitiesDocument1 pageProject Management Activitiessuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Finance For Non-Finance Executives: The Concept of Responsibility CentresDocument31 pagesFinance For Non-Finance Executives: The Concept of Responsibility Centressuresh.srinivasnNo ratings yet

- Construction Workers Fall Accidents from ScaffoldingDocument5 pagesConstruction Workers Fall Accidents from ScaffoldingNikola LopacaninNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- June-2019 LGLDocument12 pagesJune-2019 LGLQC&ISD1 LMD COLONYNo ratings yet

- Uav Design - Part IiDocument1 pageUav Design - Part IiPradeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Erosion of Concrete in Hydraulic Structures PDFDocument2 pagesErosion of Concrete in Hydraulic Structures PDFJulioNo ratings yet

- Power System Design Basics Tb08104003e PDFDocument145 pagesPower System Design Basics Tb08104003e PDFRochelle Ciudad BaylonNo ratings yet

- Top 100 Magazine - DB - FINALDocument31 pagesTop 100 Magazine - DB - FINALCharlesNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- SOP For OLDocument9 pagesSOP For OLTahir Ur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Updtaed CV - Y.vikas Singla-2018Document6 pagesUpdtaed CV - Y.vikas Singla-2018yv singlaNo ratings yet

- GPA CalculatorDocument1 pageGPA CalculatorImtinanShaukatNo ratings yet

- Opening and Closing Rank IIT CSE GENDocument1 pageOpening and Closing Rank IIT CSE GENramchanderNo ratings yet

- Six-Step Troubleshooting ProcedureDocument1 pageSix-Step Troubleshooting ProcedureNoneya BidnessNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Electrical Machinery Safety Paul LaidlerDocument41 pagesAn Introduction To Electrical Machinery Safety Paul LaidlerSafetyjoe2100% (1)

- Flowchart Hpg1034Document1 pageFlowchart Hpg1034SharulNo ratings yet

- College Course Code Data for Andhra PradeshDocument114 pagesCollege Course Code Data for Andhra Pradeshashok815No ratings yet

- Nisha's UniversityDocument2 pagesNisha's UniversityQuick FactsNo ratings yet

- MBM Engineering CollegeDocument3 pagesMBM Engineering CollegeDeep Raj JangidNo ratings yet

- Panel LG Display Lc320eun-Sem2 0Document36 pagesPanel LG Display Lc320eun-Sem2 0Carlos ChNo ratings yet

- Elastic Architecture: A B C D E F GDocument0 pagesElastic Architecture: A B C D E F GNandhitha RajarathnamNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Theory of Structures - Floor SystemsDocument31 pagesTheory of Structures - Floor SystemsLawrence Babatunde OgunsanyaNo ratings yet

- Engineering EthicsDocument48 pagesEngineering EthicsRhegNo ratings yet

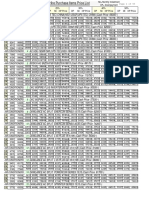

- PriceListHirePurchase Normal 1Document55 pagesPriceListHirePurchase Normal 1Muhammad HajiNo ratings yet

- D. Design For Fault ToleranceDocument8 pagesD. Design For Fault TolerancemeeNo ratings yet

- Httpbarbianatutorial.blogspot.comDocument180 pagesHttpbarbianatutorial.blogspot.comsksarkar.barbianaNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Fatigue 16.0 L01 PDFDocument70 pagesMechanical Fatigue 16.0 L01 PDFAlexander NarváezNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic code info for Caterpillar enginesDocument3 pagesDiagnostic code info for Caterpillar enginesevanNo ratings yet

- ACI 523.1 (1992) Guide For Cast-In-Place Low-Density ConcreteDocument8 pagesACI 523.1 (1992) Guide For Cast-In-Place Low-Density Concretephilipyap0% (1)

- Voltage Profile Improvement, Transmission Line Loss Reduction in Rajasthan Power System: A Case StudyDocument12 pagesVoltage Profile Improvement, Transmission Line Loss Reduction in Rajasthan Power System: A Case StudyAdvanced Research PublicationsNo ratings yet

- The Easily Mounted Floor System For Large Spans: Hoesch Additive Floor Technical InformationDocument16 pagesThe Easily Mounted Floor System For Large Spans: Hoesch Additive Floor Technical InformationIvan ŠpacNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensible Guide To J1939Document1 pageA Comprehensible Guide To J1939androNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence: From Medieval Robots to Neural NetworksFrom EverandArtificial Intelligence: From Medieval Robots to Neural NetworksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Artificial Intelligence Revolution: How AI Will Change our Society, Economy, and CultureFrom EverandArtificial Intelligence Revolution: How AI Will Change our Society, Economy, and CultureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The Fourth Age: Smart Robots, Conscious Computers, and the Future of HumanityFrom EverandThe Fourth Age: Smart Robots, Conscious Computers, and the Future of HumanityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (115)

- ChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindFrom EverandChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindNo ratings yet

- PLC Programming & Implementation: An Introduction to PLC Programming Methods and ApplicationsFrom EverandPLC Programming & Implementation: An Introduction to PLC Programming Methods and ApplicationsNo ratings yet